-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sherene Seikaly, The Matter of Time, The American Historical Review, Volume 124, Issue 5, December 2019, Pages 1681–1688, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhz1138

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A century after the victorious Allied powers distributed their spoils of victory in 1919, the world still lives with the geopolitical consequences of the mandates system established by the League of Nations. The Covenant article authorizing the new imperial dispensation came cloaked in the old civilizationist discourse, entrusting sovereignty over “peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world” to the “advanced nations” of Belgium, England, France, Japan, and South Africa. In this series of “reflections” on the mandates, ten scholars of Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and the international order consider the consequences of the new geopolitical order birthed by World War I. How did the reshuffling of imperial power in the immediate postwar period configure long-term struggles over minority rights, decolonization, and the shape of nation-states when the colonial era finally came to a close? How did the alleged beneficiaries—more often the victims—of this “sacred trust” grasp their own fates in a world that simultaneously promised and denied them the possibility of self-determination? From Palestine, to Namibia, to Kurdistan, and beyond, the legacies of the mandatory moment remain pressing questions today.

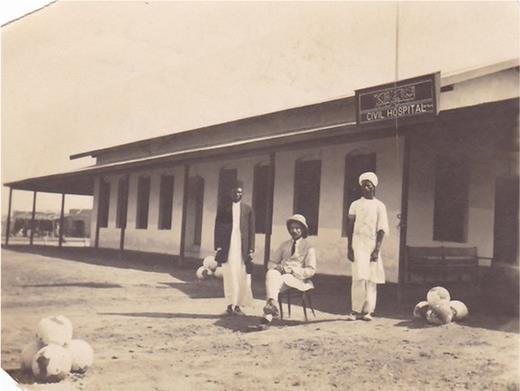

The year is 1916. An olive-skinned young man with a dapper moustache sits authoritatively on a stool in Sudan. He wears a white suit and a black tie. His back is straight and his legs are crossed, his hands folded on his lap. Two black Sudanese men stand at attention a discreet distance away. One wears a turban, the other a fez. A pith helmet crowns the young man’s disposition. It is a racialized symbol of his vulnerability to “tropical” climates and diseases. Behind the three men is the civilian hospital where they all work. The seated man, confident in his civilizational and racial superiority, is Naim Cotran (1877–1961).1 Naim was my great-grandfather. Some three decades after he posed for this photograph, the British colonial authorities he emulated would be the agents of his subordination and ultimate dispossession. But let’s remain in 1916 for now.

Who is Naim, this young man linked to the civilian hospital in Omdurman? He is a junior partner in the British and Egyptian colonization of Sudan. Sudan had been an Egyptian colony beginning in 1821. In 1882, the British occupied Egypt. Seven years later, British forces invaded Sudan and annexed it to Egypt, in an arrangement called the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium. British colonial administrators would run both countries for decades.2 From the inception of British rule, colonial authorities envisioned an independent civilian medical service as expansive as the railroads they built from Wadi Halfa to Khartoum and from the Nile River to the Red Sea. Beginning in 1901, the Sudan Medical Department, later renamed the Sudan Medical Service, would be crucial to the categorizing, mapping, and policing of Sudan as a racial state in which white rule dominated.3

Where did Naim fit in this order? He received his medical degree from the University of Maryland in Baltimore in 1901. He arrived to Sudan together with many Arab Christians from Greater Syria, today’s Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Israel/Palestine. Most of these doctors trained in Beirut at the Syrian Protestant College (American University of Beirut) or the Université Saint-Joseph. Until 1925, they outnumbered both their British and Egyptian counterparts in the Sudan Medical Service.4 The colonial governor of Egypt (r. 1883–1907), Lord Cromer, viewed Syrian Christians as superior to their Muslim brethren. The Syrian Christian, as he put it, “really is civilised,” and “from a moral, social, or intellectual point of view . . . stands on a distinctly high level.”5 British officials in Sudan adopted this logic even as Egyptians called for self-determination. Doctors like Naim, these officials assumed, were passive, apolitical, and white-adjacent.6 They were ideal recruits for the Medical Department’s coercive and militarized attempts to control sleeping sickness in southern Sudan.7

Naim Cotran in Sudan, 1916. Photograph in the author’s possession.

Initially, the Sudan Medical Department was a source of social mobility and capital accumulation for Naim. In the 1916 photograph, Naim sits, armed with his Western expertise, mediating between the Sudanese people and their colonizers. He inhabits the vanguard of a colonial temporality in which Western civilization advances through conquest. Yet even in Sudan, he began facing some colonial realities. Syrian Christian doctors performed the same medical tasks as their English, Scottish, and Irish counterparts, but they were “always subject to . . . their British superiors.”8 This secondary status in the medical hierarchy revealed the limits of the religious, sect, class, and light-skin privilege that fueled Naim’s life. Aspirational Anglophilia, which some Syrian Christians nurtured in the nineteenth century, would soon, at least for Naim, become impossible to sustain.

Following World War I, the people of Greater Syria and Iraq, Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike, were political patients in need of “civilizational therapy.”9 Categorizing and asserting control over the territorial spoils of war, the League of Nations graded the Arab provinces of the former Ottoman Empire as “A” territories. These inhabitants were “destitute” and required “nursing towards economic and political independence.”10 Unlike the people of the “B” and “C” territories—former German colonies in Africa and the Pacific—the League deemed Arab residents “semi-civilized” and capable of eventual self-rule.11 This eventuality was contingent on skin color, itself linked to notions of the “primitive.” In shaping a new international field with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, mandate government technologies intervened in “intimate and minute aspects of social life.”12 Mandate regimes drew on a long history of targeting “native” customs, traditions, lifestyles, and psychologies as objects of social engineering. Disease and the incapacity to resist it was an indicator of “backwardness.” In the words of the League of Nations’ Draft Convention on Slavery, “even [in] resistance to disease . . . [natives] differ profoundly from Europeans . . . they will only be able to adjust . . . after a long period of evolution.”13 In Sudan, Naim occupied the position of the “superior” doctor, albeit a second-tier one, healing the “backward” natives. When he returned to Palestine to establish his private practice in the early 1920s, he faced new formulas.

In the League of Nations’ logic, Naim was now one of the “backward” subjects crawling from a “primitive present” toward a “modern future.”14 Armed with new social, technical, and legal tools, the European “guardians” sought both profit and “native welfare.” They would train the crawling subject to stand upright. How long the tutelage might last or when it might end was nowhere to be found in the plans for realizing the “sacred trust of civilization.”15 The mandates system introduced into international law a temporality of deferral: everyone under mandate rule was confined to the “waiting room of history.”16 Iraqis, Syrians, Lebanese, and Transjordanians used and resisted mandate institutions to imagine a variety of political futures.

But in Palestine, Naim found that the British officials he had formerly emulated were “ruling but not governing.”17 Unlike their Lebanese, Syrian, Transjordanian, and Iraqi counterparts, Palestinians under the mandate regime were denied access to representative institutions and developmental infrastructures. As a Palestinian native, Naim would soon realize, he was not worthy of “treatment.” The Balfour Declaration of 1917, which became a juridical pillar of British mandatory rule, afforded Palestinian Muslims and Christians civil and religious but not political rights. The declaration and the mandate defined these Muslims and Christians by what they were not. They became “non-Jews.”18 This definition necessitated territorial, national, and ethnic partitioning between Palestine’s small Jewish communities, about 5 percent of the inhabitants of Palestine in 1917, and their Christian and Muslim brethren. Palestinian Muslims and Christians became rootless “natives” unworthy of self-determination.19 The British mandate hinged on using the language of the “native” while denying that native a political name and a territory. Naim stood as a sort of specter, a present absentee.

The British mandate in Palestine envisioned a future for the land, but not for its people. From the Permanent Mandates Commission’s perspective, these Palestinians kept the country in a state of stagnation.20 The land needed an “able and energetic” people to facilitate its arrival to a modern temporality.21 Naim’s future was held in suspension. He inhabited a temporality not of deferral but of permanent abeyance.22 British officials sought to simply maintain the status quo for Palestinian Muslims and Christians: don’t develop, don’t invest, don’t fund. Given the British mandate’s commitment to the Jewish National Home policy, the Palestinians could never be developmental subjects. Only the Great Revolt of 1936–1939 and later World War II forced British colonial officials to invest in some form of Palestinian developmentalism.23 British rule was so parsimonious that it was only when war induced new capital flows, which facilitated Palestinians’ escape from indebtedness, that many villages paved roads and built schools. Urban middle- and upper-class Palestinians did not have these problems. And families like mine could draw on a broad network of missionary educational infrastructures. Palestinians of all classes struggled for their present and nourished heterogeneous visions of the future, but their possibilities were increasingly foreclosed. Had Naim been Lebanese, Syrian, Iraqi, or Transjordanian, he would have experienced eventual, if only formal, independence. But Naim, like all Palestinians, was dispossessed and his homeland dismembered.

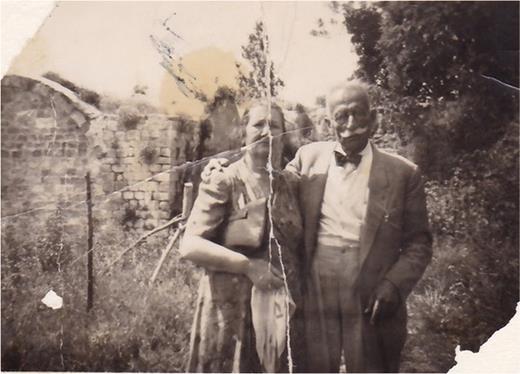

Naim and Aniseh Cotran in Palestine, 1930. Photograph in the author’s possession.

The conditions of presence/absence and temporal abeyance would mark Naim until his death. Scholars usually think of these phenomena as beginning after 1948 with the permanent temporariness of refugee life and the 1948 Israeli emergency regulation that shaped the Palestinian as present on the land but “absent” in law.24 Neither this form of temporality nor this form of presence began in 1948. It was the British mandate and its embrace of Zionism that introduced these subjectivities and temporalities. The troubled twin birth of the Israeli state and the Palestinian refugee condition would consolidate them.

When the war between Arabs and Jews began in 1948, Naim’s children and grandchildren fled to Egypt and Lebanon. Naim and his wife, Aniseh (1896–1978), struggled to remain in the midst of the Nakba, or catastrophe. Naim maintained his faith in bureaucracy. He was confident. He knew the rules. He understood the importance of evidence. For four years, he gathered certificates, deeds, and maps for the lands he owned in the village of Nahr al-Nabi’a, about eight miles from Acre. These lands, he insisted time and again, were “my private property.”25 He petitioned. He appealed. A formidable wall of bureaucracy excluded him at each turn.26 Between June and November of 1949, Naim and Aniseh found their orchards burned.27 Two years later, impoverished and defeated, they joined their family in exile.

Time shifted. It became suspended between crisis and stasis. “The matter of time is a very important factor especially to us refugees,” Naim explained.28 He lived in the fractures between immediate emergency and long-term displacement.29 In exile and in the throes of ongoing catastrophe, he maintained his faith in the rules and his rights to claim them. “I am a Palestinian refugee from the city of Acre . . . I am an old man . . . I have a family to support.”30 Naim penned such pleas from 1951 until his death a decade later. He compiled, labeled, and organized an inventory of failed attempts to secure the return of 660 Israeli liras he had deposited in Bank Leumi in Haifa before exile.31 He petitioned to buy time that was no longer his own. He petitioned for restitution. He petitioned until his death. Sometimes I wonder if he petitioned to death.

Naim and Aniseh Cotran in their orchards in Nahr al Nabi’a, 1949. Photograph in the author’s possession.

I recently stumbled across some papers that Naim left behind, an archive full of details and silences. Naim was not just a refugee. He was that confident man on the stool in Sudan, holding fast to imperial aspirations and conceptions of superiority. At different times he had been a medical doctor, a landowner, a slaveholder, and a colonial official. The mandate was one moment in the narrowing of his subjectivities. While reading his papers, I realized that Naim has been haunting me for at least two decades. I wrote a book about him without knowing it. He is today my ghostly teacher, imparting lessons on the relationship between subjectivity and historiography and the intersections between history and the lived present. He was a perpetrator and a victim. He was a colonial official and a colonized subject. His multiple subject positions appear contradictory today. They are an invitation to escape colonial and national epistemologies. After 1948, Naim would live in a permanent state of temporariness. He persisted in the midst of catastrophe and abeyance. Today, Palestinians’ capacity for self-rule is still in question.32 Today, Palestinians plan not for the future, but despite it.33 Given impending environmental doom, the significance of the matter of time and the insistence on planning despite the future might be useful lessons for us all.34

Sherene Seikaly is Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Men of Capital: Scarcity and Economy in Mandate Palestine (Stanford University Press, 2016). She is following the trajectory of her great-grandfather in her forthcoming book project, provisionally titled From Baltimore to Beirut: On the Question of Palestine. This project was supported in part by funding from the University of California Presidential Faculty Research Fellowship in the Humanities.

Notes

There are conflicting accounts of Naim Cotran’s birthdate. He claimed to be seventy-one in 1948, which would make his birth year 1877.

See Eve M. Troutt Powell, A Different Shade of Colonialism: Egypt, Great Britain, and the Mastery of the Sudan (Berkeley, Calif., 2003).

David Theo Goldberg, The Racial State (Oxford, 2002).

Heather Bell, Frontiers of Medicine in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1899–1940 (Oxford, 1999), 41.

Evelyn Baring, Earl of Cromer, Modern Egypt, 2 vols. (London, 1908), 2: 218.

Sarah M. A. Gualtieri, Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora (Berkeley, Calif., 2009).

As Heather Bell shows, military influence over civilian medicine in Sudan persisted well into the 1920s. As part of the sleeping sickness campaign in southern Sudan, people were subjected to excruciating inspection and forcible relocation, and villages were burned to the ground. “Detention in the sleeping sickness camps . . . lasted years and frequently ended in death.” Bell, Frontiers of Medicine in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 153.

Ibid., 41.

Antony Anghie, Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law (Cambridge, 2004), 135.

J. C. Smuts, “The League of Nations: A Practical Suggestion,” reprinted as Document 5, “The Smuts Plan,” in David Hunter Miller, The Drafting of the Covenant, 2 vols. (1928; repr., New York, 1971), 2: 23–60, here 26.

Cyrus Schayegh and Andrew Arsan, The Routledge Handbook of the History of the Middle East Mandates (New York, 2015). Julia Elyachar draws on this concept of the semi-civilized in international law in her book Semiotic Political Economy: Social Infrastructure, Phatic Labor, and the Semi-Civilized (forthcoming from Duke University Press), analyzing the place of the semi-civilized in the Western imaginary of the civilized/primitive divide. See also Umut Özsu, “The Ottoman Empire, the Origins of Extraterritoriality, and International Legal Theory,” in Anne Orford and Florian Hoffmann, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law, Oxford Handbooks Online, https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/law/9780198701958.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198701958-e-7.

Anghie, Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law, 156.

“Draft Convention on Slavery Recommended by the Sixth Assembly,” League of Nations Official Journal 7, no. 11 (1926): 1539–1546, here 1541.

Frederick Cooper, “Modernizing Bureaucrats, Backward Africans, and the Development Concept,” in Frederick Cooper and Randall Packard, eds., International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley, Calif., 1997), 64–92.

Susan Pedersen, The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire (Oxford, 2015), 130, 1.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, N.J., 2000), 8.

These are the words of a group of textile merchants in Palestine in the 1940s. See Sherene Seikaly, Men of Capital: Scarcity and Economy in Mandate Palestine (Stanford, Calif., 2016), 91–100, quote from 91.

The Balfour Declaration, conveyed in a letter from Arthur James Balfour to Lord Rothschild dated November 2, 1917, reads in full: “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

Michelle U. Campos, Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (Stanford, Calif., 2011), 12.

Permanent Mandates Commission, Minutes, vol. V, 188, as cited in Quincy Wright, Mandates under the League of Nations (Chicago, 1930), 232.

Ibid.

Ilana Feldman, Governing Gaza: Bureaucracy, Authority, and the Work of Rule, 1917–1967 (Durham, N.C., 2008).

Charles Anderson, “From Petition to Confrontation: The Palestinian National Movement and the Rise of Mass Politics, 1929–1939” (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 2013); Seikaly, Men of Capital.

In December 1948, Israel issued the “Emergency Regulations on the Property of Absentees.” An absentee was any person who owned property in Israel and who on or after November 29, 1947, had gone outside Israel. As Geremy Forman and Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar show, this legislation was so broad that it included technically everyone, but it was the Palestinians who were now absentees. See Forman and Kedar, “From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22, no. 6 (2004): 809–830. For Naim’s struggle with this regulation, see Sherene Seikaly, “How I Met My Great-Grandfather: Archives and the Writing of History,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 38, no. 1 (2018): 6–20. There are two issues at stake in the category of the “present absentee.” Israeli regulations, later embodied in law, facilitated the expropriation of the property of refugees outside of the part of Palestine that became Israel. There are two kinds of “present absentees.” On the one hand, there are those refugees outside of the part of Palestine that became Israel. Israeli regulations, later embodied in law, facilitated the expropriation of the property of these refugees. On the other hand, there are the “present absentees” who were physically present in the part of Palestine that became Israel but lost property rights because they were allegedly not in the right place at the right time.

Naim Cotran to Sir Boyer, Custodian of Arab Property, Acre, January 5, 1949 (handwritten draft), in the author’s possession.

Julie Peteet, “Closure’s Temporality: The Cultural Politics of Time and Waiting,” South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 1 (2018): 43–64.

It is not clear who set the fire. See Seikaly, “How I Met My Great-Grandfather.”

Naim Cotran to United Nations Palestine Reconciliation Commission (UNPRC), February 1, 1957, in the author’s possession.

Ilana Feldman, Life Lived in Relief: Humanitarian Predicaments and Palestinian Refugee Politics (Berkeley, Calif., 2018).

Naim Cotran to UNPRC, January 10, 1956; Naim Cotran to UNPRC, torn, second page, not dated, in the author’s possession.

The Israeli lira was Israel’s currency until 1980, when the Bank of Israel issued the new Israeli shekel. For the story of Palestinian bank accounts after 1948 and the economic and monetary dimensions of statelessness, see Sreemati Mitter, “A History of Money in Palestine: From 1900s to the Present” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2014).

Rashid Khalidi, “The Neocolonial Arrogance of the Kushner Plan,” New York Review of Books, June 12, 2019, https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/06/12/the-neocolonial-arrogance-of-the-kushner-plan/. See also Jonathan Swan’s interview with Jared Kushner on Axios, which aired on HBO on June 2, 2019, https://www.axios.com/jared-kushner-security-clearance-donald-trump-f7706db1-a978-42ec-90db-c2787f19cef3.html.

Karem Rabie, Palestine Is Throwing a Party and the Whole World Is Invited: Private Development and State Building in the West Bank (forthcoming from Duke University Press).

Naomi Klein, “Let Them Drown: The Violence of Othering in a Warming World,” London Review of Books 38, no. 11 (June 2, 2016): 11–14; and Andreas Malm, “The Walls of the Tank: On Palestinian Resistance,” Salvage, May 1, 2017, http://salvage.zone/in-print/the-walls-of-the-tank-on-palestinian-resistance/.