The ‘Harvey Effect’ Takes Down Leon Wieseltier's Magazine

The legendary intellectual’s fledgling publication, set to launch this month, is being suspended amid allegations of past workplace misconduct.

The spell of sexual harassment accusations against powerful men in Hollywood and media intensified on Tuesday with allegations of “workplace misconduct” against Leon Wieseltier, the legendary former literary editor of The New Republic, a contributing editor to The Atlantic, and a long-time fixture in Washington and New York City social circles.

“For my offenses against some of my colleagues in the past I offer a shaken apology and ask for their forgiveness,” Wieseltier said in a statement, first reported by Politico. “The women with whom I worked are smart and good people. I am ashamed to know that I made any of them feel demeaned and disrespected. I assure them that I will not waste this reckoning.” Wieseltier has not yet responded to my request for an interview.

The episode swiftly halted the publication of Wieseltier’s previously forthcoming culture magazine, which was set to launch at the end of the month, the publication’s financial backer said in a statement. “Upon receiving information related to past inappropriate workplace conduct, Emerson Collective ended its business relationship with Leon Wieseltier, including a journal planned for publication under his editorial direction. The production and distribution of the journal has been suspended,” a spokesperson for the group told The Atlantic.

Emerson Collective, an organization run by the billionaire investor and philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs, was to unveil Idea: A Journal of Politics and Culture on Oct. 31. (Emerson Collective acquired a majority share of The Atlantic in September.)

It wasn’t immediately clear how the allegations first reached Emerson Collective. Wieseltier was named—along with more than five dozen other men who work in journalism or publishing—on an anonymous spreadsheet titled “SHITTY MEDIA MEN” that quietly, and then less quietly, circulated in national media circles last week. (The Atlantic obtained a copy of the spreadsheet, but is not publishing it because the allegations are anonymous and unverified.) Anonymous charges against the men were wide-ranging, and spanned from acting “creepy af” in online conversation—“af” being an abbreviation for “as fuck”—to physical assault and rape. Wieseltier’s alleged misconduct, according to the unverified, anonymous spreadsheet, was “workplace harassment.” It’s not clear whether Emerson Collective saw the spreadsheet.

At the same time, a group of more than a dozen women who once worked at TNR started an email thread to discuss their experiences with Wieseltier—and to hatch a plan for how to make those experiences public.

Several women who worked with Wieseltier described him to me as intellectually seductive and charming—even charismatic. He’s long had a reputation for being genuinely interested in the journalistic work of young women, especially at a time when the industry was even more male dominated than it is today. He wasn’t just a leader of the magazine at TNR, but a cultural arbiter there—which meant his opinion of you mattered, several women said. It was dangerous, one former staffer told me, to get on his bad side.

Nearly a dozen journalists who have worked with Wieseltier told me they are unsurprised by the allegations against him. All of the women I talked to had their own “Leon stories,” which included everything from being called “sweetie” in the workplace to unwanted touching, kissing, groping, and other sexual advances.

My colleague Michelle Cottle, a former TNR senior editor who is now a contributing editor at The Atlantic, told me about the time Wieseltier suggested they get a drink at the bar of a well-known luxury hotel in New York City where he was staying, only to declare that it was too crowded. Instead, they could go to his room, and order a bottle of champagne, Wieseltier offered. He delights in making women sexually uncomfortable, she said.

At TNR, there was frequently talk of Wieseltier’s possible dalliances with young women writers, and he relished this kind of gossip, three separate acquaintances of Wieseltier told me. They described him as someone who bragged graphically about sexual encounters the way a teenaged boy might. Two former colleagues described him in separate conversations as “lecherous.”

The suspension of Wieseltier’s new magazine comes after a series of blockbuster scoops by The New York Times detailing a decades-long pattern of alleged sexual harassment by Harvey Weinstein, the now-infamous film producer. Weinstein and Wieseltier have similar starpower within their industries. “Wieseltier is, in sum, well on his way to achieving the best kind of American celebrity,” Vanity Fair wrote in a 1995 profile, “being famous to the famous.”

Yet even after a week of mounting accusations against powerful men in several industries, and even in Washington—a town accustomed to sex scandals—the accusations against Wieseltier are electrifying. It’s not that Wieseltier is universally liked. Quite the opposite—though he is admired by many for his erudite cultural criticism, and by many of the authors who wrote for him at TNR. He is some combination of beloved and despised; his reputation as a philosopher king is perhaps equaled by his reputation for being a machiavellian operator. Wieseltier’s observers have, in one case in the span of two sentences, described his persona as both “saintly” and “thuggish,” as a writer for The Nation put it in 2014. (Wieseltier himself wrote, in a lauded 1994 essay on identity and culture, “I hear it said of somebody that he is leading a double life. I think to myself: Just two?”)

“The nice thing about everybody speaking their mind is that social opprobrium will do its work,” Wieseltier said in a conversation published by The New York Times last year. “If you say something really disgusting, you will be vilified.”

“I feel very uncomfortable without controversy,” he added. “If the stakes are high about important questions — matters of life and death or the future of the culture — it’s inevitable. You have to argue ferociously.”

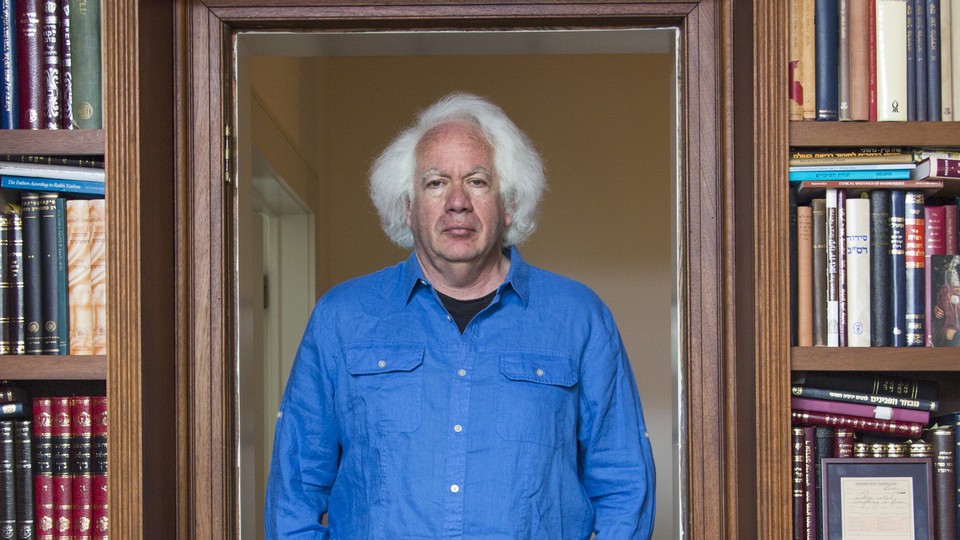

My colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates has pointed out that Wieseltier can be “gleefully mean.” In the 1980s, Wieseltier and another TNR essayist, Charles Krauthammer—now a columnist at The Washington Post—were known to so dislike each other that they attended the same editorial board meeting for years without speaking to each other, according to a1989 New York Times article. Wieseltier’s many intellectual feuds—unspooling over his three decades in the literary limelight—are as famous as his halo of Doc-Brown-white hair. The Times once described his enemies as “legion.” The vendettas have been so numerous as to perplex even his confidants. Wieseltier is, as a result of all this, one of the best known intellectuals on the East Coast.

That includes a thick tangle of connections to Atlantic Media, the parent company of The Atlantic, where several of Wieseltier’s former colleagues and friends now work. Plenty of Wieseltier’s “intellectual grudge matches,” as The New York Times once described them, have been with The Atlantic’s writers—including a longstanding beef with his former TNR colleague Andrew Sullivan, formerly of The Atlantic, who has described their relationship as one of “profound animosity.” Jeffrey Goldberg, The Atlantic’s editor-in-chief, has both publicly thanked Wieseltier (in the acknowledgements section of Goldberg’s 2006 book) and sparred with him (in various blog posts and interviews) over the years.

Wieseltier formally joined The Atlantic as a contributing editor in 2015, with his most recent essay published in March 2016. Though he is not a regular presence in the newsroom, it was Wieseltier who first suggested Powell Jobs as a potential buyer for The Atlantic, the company’s chairman, David Bradley, told staffers in a July memo. Reached via text message in London, where he is visiting the magazine’s England bureau, Goldberg couldn’t say whether Wieseltier would remain a contributor. “This news just broke,” he told me. “We’ll turn to this masthead question as soon as we reasonably can.”

The women who worked with Wieseltier, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s, felt he could make or break their careers. His role as a mentor to female colleagues, however, was somewhat complicated by his louche reputation. A 1999 New York Times Magazine profile of Wieseltier described him as having “squired a sequence of ‘extremely beautiful, alluring girlfriends.’” That same profile describes a period of “well-reported excesses, which included heavy drinking and cocaine binges” and “a flurry of infidelities” which allegedly ended his first marriage and cast considerable doubt over his literary future. “For Wieseltier, the tension between the scholarly and the sensual is not easily resolved,” Sam Tanenhaus wrote in the Times article. “Until recently, majority opinion in the literary-cultural world—the narrow, gossipy corridor that stretches from Boston to Washington, with tentative windings in the direction of London and Los Angeles—held that not even the most rigorous polishing could restore the sheen to his tarnished image.” Yet Wieseltier went on to write a widely acclaimed memoir, and continued in his role at The New Republic for nearly two decades, until he and much of the rest of the editorial staff walked out in protest of the company’s digital strategy under new ownership. Now, as Wieseltier’s former colleagues reckon with his alleged inappropriate behaviors, several of them told me they worry they were complicit in enabling him over the years.

It is not clear whether Wieseltier will look for another funder for his journal, which had a staff of five employees.