Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine.

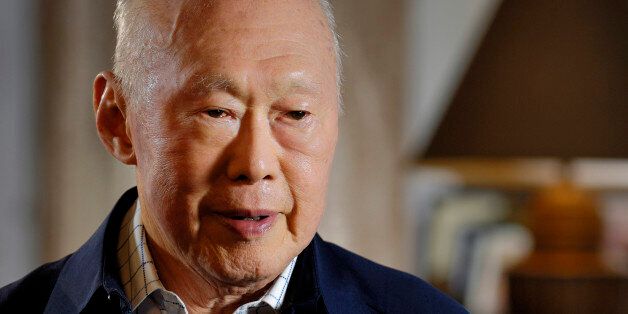

Though the founding father of a tiny country on the tip of the Malay peninsula, Lee Kuan Yew was one of the giants of the arriving Asian century. Not only did he miraculously transform the impoverished colonial entrepôt of Singapore, rife with drugs and prostitution, into a gleaming model city-state of the 21st century; his practical vision of soft-authoritarian capitalism also became the template for Deng Xiaoping’s “opening up and reform” in China, laying the basis for the rise of a prosperous East Asia.

We met twice, in 1992 and 1995, in steamy Singapore, sitting in the icily air-conditioned salon at Istana, the former British governor’s residence, looking out over the manicured lawns, as we delved deep into the contrasts of Confucian communitarianism and Western individualism. We met one last time in a snowbound chalet in Davos, Switzerland, in 1999 after his formal retirement as “senior minister” and graduation to “minister mentor,” the sage behind the throne.

Here are excerpts of those interviews:

Nathan Gardels | Now that the Cold War is over, isn’t a new conflict arising between East Asian “communitarian” capitalism and American-style “individualistic” capitalism? Further, isn’t this economic conflict rooted in the deeper differences between civilizations: the authoritarian bent of Confucian culture and the extreme individualism of Western liberalism?

Lee Kuan Yew | This is one facet of the problems that arise in a global economy. Latecomers to industrial development have had to catch up by finding ways of closing the gap.

As it has turned out, more communitarian values and practices of East Asians — the Japanese, Koreans, Taiwanese, Hong Kongers and Singaporeans — have proven to be clear assets in the catching-up process. The values that East Asian culture upholds, such as the primacy of group interests over individual interests, support the total group effort necessary to develop rapidly. But I do not see the conflict you describe as competition between two closed systems.

The original communitarianism of Chinese Confucian society has degenerated into nepotism, a system of family linkages, and corruption, on the mainland. And remnants of the evils of the original system are still found in Taiwan, Hong Kong and even Singapore.

“The original communitarianism of Chinese Confucian society has degenerated into nepotism, a system of family linkages, and corruption, on the mainland.”

Hong Kong and Taiwan differ from China, of course, because Confucian ways have been moderated by 100-odd years of British rule in Hong Kong’s case and 50 years of Japanese rule in Taiwan.

China itself is now in the process of sloughing off not only the communist system, but also those outdated parts of Confucianism that prevent the rapid acquisition of knowledge needed to adjust to new ways of life and work.

So, I see this conflict as a part of interaction and evolution in one world. Systems are not developing in isolation.

Having said this, America and East Asia are, of course, very different cultures. Chinese culture grew up in isolation from the rest of the world for thousands of years and then extended itself into Korea, Japan and Vietnam. From the other end of the continent, Indian culture spread out and reached as far as Thailand and Cambodia.

So, one can take a broad brush and shade East Asian culture over Korea, China, Vietnam and Japan. Indian-Hindu culture in a very broad sense covers Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Burma and Southeast Asia.

Then there is an overlay of Muslim culture, completely different from Hindu culture, which is also to be found now in Pakistan, Bangladesh and parts of India. There are 190 million Muslims in Southeast Asia, primarily in Malaysia and Indonesia. Thailand is more Buddhist, like Burma.

Seeing the ancient, complex cultural map of this part of the world, can we all of a sudden accept universal values of democracy and human rights as defined by America? I don’t think that it is possible. Values are formed out of the history and experience of a people. One absorbs these notions through the mother’s milk.

As prime minister of Singapore, my first task was to lift my country out of the degradation that poverty, ignorance and disease had wrought. Since it was dire poverty that made for such a low priority given to human life, all other things became secondary.

“My first task was to lift my country out of the degradation that poverty, ignorance and disease had wrought. Since it was dire poverty that made for such a low priority given to human life, all other things became secondary.”

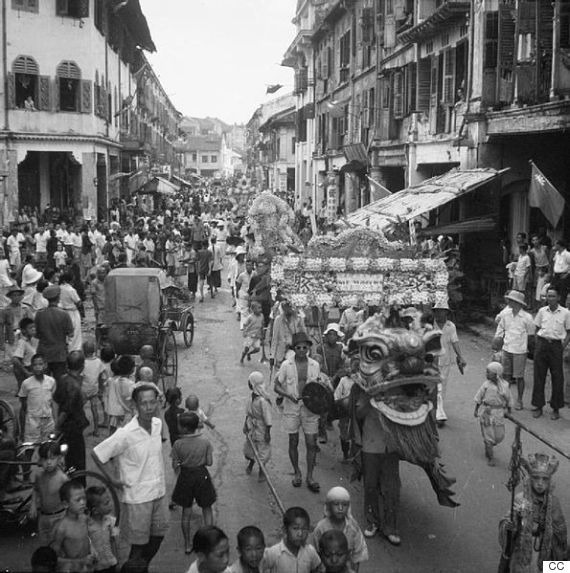

British Reoccupation of Singapore, 1945, Imperial War Museum

British Reoccupation of Singapore, 1945, Imperial War Museum

So, our values are different, as they always have been. But now, television, the Internet, satellites and aircraft have brought us all into one world. After taking our separate paths for thousands of years, we now meet, and there is total misunderstanding.

“As a man of two cultures, I have learned that one cannot change core values overnight just by exposure to a different culture.”

I am one who has been exposed to both worlds: Singapore was governed by the British but it was basically an Asian society, so I could see what British standards were like, and compare and contrast them to Asian standards. And I was educated in Britain for four years and saw how the British comported and governed themselves. As a man of two cultures, I have learned that one cannot change core values overnight just by exposure to a different culture.

For Asia, I think that over the next one, two, or perhaps three generations (with each generation marking 20 years), there will have to be adjustments. So, a hundred years from now, I’m sure Europeans, East Asians and Americans will arrive at something approximating universal values and norms.

UNIVERSAL NORMS

Gardels | Universal values in terms of human rights?

Lee | Let’s call it “human behavior” in general. The only exception might be the Muslims, because Islamic injunctions about how to punish adultery by stoning to death, or thieving by cutting off hands, are written down in the holy Quran. I am not sure Muslims are going to change as easily as Buddhists or Hindus. But I cannot see them remaining totally unchanged either. After all, for them to catch up, even if only to modernize their weaponry so they can get the big bomb and blow up Israelis, they have to train and equip a whole generation of young minds with the scientific approach to the solving of problems. Inevitably, that critical scientific mentality must bring about change in their perceptions of core values. But it is a long and slow process. In sum, I don’t think a resolution in the U.S. Congress can change China or anybody else.

Gardels | In principle, do you believe in one standard of human rights and free expression?

Lee | Look, it is not a matter of principle but of practice. In the technologically connected world of today, everybody can watch the Tiananmen crackdown on TV. Today, transportation is subsonic but in another 20 years your son will be able to travel at supersonic speeds; instead of 15 hours, in just a few hours he will be able to go from New York to Singapore.

In such a world, no society can be protected from the influence of another. But that doesn’t mean that all Western values will prevail. I can only say that if Western values are in fact superior insofar as they bring about superior performance in a society and help it survive. If adopting Western values diminishes the prospects for survival of a society, they will be rejected.

For example, if too much individualism does not help survival in a densely populated country such as China, it just won’t take. At the same time, however, much Chinese leaders berate Americans because the U.S. is the world’s major power, the leadership knows that the Americans have in fact been the least exploitive of China when compared to the Japanese or Europeans. This reality is deep in the historical memory of the Chinese people. The Americans left behind universities, schools and scholarships for educating doctors.

Of course, the Americans tried to convert everybody to Christianity. In fact, today there are factions in Chinese society, not just in the communist leadership, that believe the Americans are the most evangelistic of the whole lot: the others will just trade with you and leave you alone but Americans will come and want to convert you. Now it’s not Christianity but human rights and democracy American-style! The Chinese leaders call it “human rights” imperialism.

TIANANMEN SQUARE

Gardels | But wasn’t the Tiananmen movement, with its replica of the Statue of Liberty, really a cry for “human rights and democracy American-style?”

Lee | I would not define what happened in the spring of 1989 as a movement for democracy. It was a movement for change from the total control of the Communist Party. If you had questioned a cross-section of the student leaders and others who participated, many of them would have had no clear idea of what they wanted in place of the Chinese Communist Party that governs that immense land.

Really, to young people, democracy means “More freedom for me!” But how does one govern one-quarter of humanity on that basis? By what principles? By what methods? The demonstrators didn’t think it through. “Let’s make things better.” “Let’s stop this corruption.” “Let’s stop nepotism.” “Let’s have more freedom of association.” That is all they really wanted.

Tiananmen Square, 1989

Tiananmen Square, 1989

The tragedy of Tiananmen was that the participants got carried away by the dynamics of mass emotion in a very densely populated city. Their grievances exploded into one big demonstration, and it became a frontal challenge to the Communist Party, and a personal challenge to Deng Xiaoping as a leader.

As the events progressed, the slogans that were being put up became increasingly strident. I watched what was on Chinese TV and in the Chinese newspapers. The whole thing had evolved into an attack on Deng.

In my view, that was unwise. There is, after all, no tradition in Chinese history of satirizing the emperor. To do a (satirical) Doonesbury cartoon of the emperor is to commit sedition and treason. About four or five days before the end, I heard a clever little doggerel making fun of Deng. I thought, God, this is it. Either they will get away with this bit of irreverence and disrespect, in which case Deng is finished, or Deng is going to teach them a lesson. Deng slapped them down — with an unnecessary use of armor, in my view — to show them who was the boss.

Why such force, I asked myself? These are not stupid people. They know what the world will think. My only explanation is that Deng must have feared that if the movement in Beijing was repeated in 200 major Chinese cities, he would not be able to control it. As with traditional Chinese rulers, he set up a clear, if brutal, example for all to see.

Gardels | So Deng was afraid of the pro-democracy movement erupting in 200 cities, among the 20 percent of the population that doesn’t live in the countryside, with its 800 million peasants.

Doesn’t this point up the problem of how one central policy can’t rule two Chinas — the urban and the rural — at the same time? You yourself have argued for a “twin-track” policy that allows more freedom in the cities where the educated classes demand it. Otherwise economic reform will falter.

Lee | No, not freedom. They will have to have participation in the way they are governed. Please, let’s use neutral words, because when you use words such as “freedom” and “democracy” you scare the Chinese. Since Tiananmen, these have become code words for subverting China. So when you talk to them like that, they say, “Well, okay, relations with the West are off. It is them or us. And it has got to be us.”

I would say this to China’s leaders: once 20 to 30 percent of the urban population (out of each year’s student cohort) has a college education, the next 40 to 50 percent are in polytechnic or technical school, and the rest have a general education of about US tenth-grade level, you can no longer just give orders from the top down if you want to succeed in your economic development. With today’s high technology, you just can’t squeeze the maximum productivity out of advanced machinery without a self-motivated and self-governing work force. What is the point of having $100 million worth of machinery in a factory if you can’t get 95 percent productivity or more out of it through the use of quality circles, involving engineers in the productivity process, as the Japanese do?

So the process of economic advancement requires participation. One simply cannot ask a highly educated work force to stop thinking when it leaves the factory. A broader participation in the larger society must take place or the whole economic effort will collapse.

WANING WEST? NOT SO FAST

Gardels | As a result of Deng’s policies, for the first time in 500 years, the West is no longer the formative influence on world affairs. According to the World Bank, China will be the world’s largest economy by the year 2020. Is this the last “Western” century?

Lee | Not so fast. I wouldn’t put it so apocalyptically. First of all, when we are talking about Asia, we are really talking about China. Asia’s influence on the world without China would not be all that much.

Now, China may well become the world’s largest economy, but will it become the most admired and the most influential society? Will it have the technology, the standard of living, the quality of life, the lifestyle that others want? Have they got songs, lyrics and ideas that engage people? That is going to take time.

What will not take a long time is for China, and hence Asia, to say to the West “stop pushing us around.” When Britain was eased out of its position as the world’s number-one power, America took over effortlessly. It was uncomfortable for the British, but they gave way with grace. Britain needed America’s help in two world wars. She paid dearly for that help and had to dismantle her empire. So the American takeover was accompanied with much grace on both sides.

As Harold Macmillan put it, the British decided to play the role of the Greeks to the Romans; in other words, to help America absorb Britain’s experience, just as the Greeks helped the Romans run their empire. Washington was the new Rome for Britain. Both shared a common language and a common culture, at least originally.

But now, for America to be displaced, not in the world, but only in the western Pacific, by an Asian people long despised and dismissed with contempt as decadent, feeble, corrupt and inept is emotionally very difficult to accept.

The sense of cultural supremacy of the Americas will make this adjustment most difficult. Americans believe their ideas are universal — the supremacy of the individual and free, unfettered expression. But they are not — never were.

In fact, American society was so successful for so long not because of these ideas and principles, but because of a certain geopolitical good fortune, an abundance of resources and immigrant energy, a generous flow of capital and technology from Europe, and two wide oceans that kept conflicts of the world away from American shores.

It is this sense of cultural supremacy which leads the American media to pick on Singapore and beat us up as authoritarian and dictatorial, an over-ruled, over-restricted, stifling and sterile society. Why? Because we have not complied with their ideas of how we should govern ourselves. American principles and theories have not yet proven successful in East Asia — not in Taiwan, Thailand or South Korea. If these countries become better societies than Singapore, in another five or 10 years, we will run after them to adopt their practices and catch up.

And now in America itself there is widespread crime and violence, children kill each other with guns, neighborhoods are insecure, old people feel forgotten, families are falling apart. And the media attack the integrity and character of your leaders with impunity, drags down all those in authority and blame everyone but themselves.

Gardels | Zbigniew Brzezinski has said, “What worries me most about America is that our own cultural self-corruption — our permissive cornucopia — may undercut America’s capacity not just to sustain its position in the word as a political leader, but eventually even as a systemic model for others.”

Lee | I wouldn’t put it in that colorful way, but he is right. It has already happened. The idea of individual supremacy and the right to free expression, when carried to excess, has not worked. They have made it difficult to keep American society cohesive. Asians can see it is not working.

Gardels | In other words, “Extremism in the name of liberty is a vice.”

Lee | Those who want a wholesome society safe for individual citizens to exercise their freedom, for young girls and old ladies to walk in the streets at night, where the young are not preyed upon by drug peddlers, will not follow the American model. So we look around, at the Japanese or the Germans, for a better way of doing things.

Though America is no longer a model for social order, many other parts are obviously worth emulating. How Americans raise venture capital, take risks and start up new firms is worth emulating. I don’t see that in France, Germany or Japan.

That is not just creativity of ideas, but the ability to bring the new ideas to fruition and test them in the marketplace. That is all greatly admired around the world. But this free-for-all, this notion that all ideas should contend and there will be blinding light out of which you’ll see the truth — ha!

Singapore, 2015

Singapore, 2015

Gardels | Isn’t that innovative spirit, the capacity for initiative, part and parcel of a society where all individuals are free to create?

Lee | No, it is not. The top 3 to 5 percent of a society can handle this free-for-all, this clash of ideas. For them, you can turn an egg on its head and ask, “Will this work?” but if you do this with the mass of people in Asia, where over 50 percent of the people are not literate and the other 50 percent are just barley literate, you’ll have a mess.

The avant-garde may lead a society forward; but if the whole society becomes like the avant-garde, it will fall apart. Let the avant-garde lead the way, and then when they have debugged the system, others can follow.

In this vein, I say, let them have the Internet! How many Singaporeans will be exposed to all these ideas, including some crazy ones, which we hope they won’t absorb? Five percent? Okay.

That is intellectual stimulation that can provide an edge for society as a whole. But to have, day by day, images of violence and raw sex on the screen, the whole society exposed to it, it will ruin a whole community.

Gardels | Isn’t that an outmoded view in the Information Age? I cite Shimon Peres: “The power of governments was largely due to the monopoly they had over the flow of knowledge. But ever since knowledge has become available to all, a new dynamic has been set in motion and cannot be stopped. Each and every citizen can become his own diplomat, his own administrator, his own governor. The knowledge to do so is available to him. He is no longer inclined to accept directives from on high as self-evident. He judges for himself.”

Lee | That is true only to a point. Every lawyer knows the law, yet every lawyer at the bar knows who are better lawyers and who are the best.

The more knowledge there is the more people know who is best qualified to do the job. In a cabinet meeting, every minister gets the same information. But the ministers who tip the balance in reaching a decision are not the ones who have clever arguments, but those whose judgments are respected because repeatedly, from experience, they have been proven right.

It is not the information that makes the difference, but better use of information through better judgment. We are not all equally gifted or talented. This will still be true in the information society.

NO PLACE IS AN ISLAND ANYMORE

Gardels | America’s most prominent futurist, Alvin Toffler, has said, “I used to think of Lee Kuan Yew as a man of the future. Now I think of him as a man of the past. You can’t try to control information flows in this day and age.” Bill Gates of Microsoft said something similar: “Singapore wants to have its cake and eat it, too.” They want to be wired into cyberspace, but keep control over information that affects their local culture.

“But no place is an island anymore,” Gates says. Not even Singapore. If you get the Internet, you will get Madonna’s lewd lyrics and New York Times columnist Bill Safire calling you a dictator. Are you a man of the past, or a man of the future? Can you have your cake and eat it, too?

Lee | I know two fundamental truths: First, in an age when technology is changing so fast, if we don’t change we’ll be left behind and become irrelevant. So you have to change, fast. Second, how you nurture the children of the next generation has not been changed, whatever the state of technology.

From small tribes to clans to nations, the father-mother-son-daughter relationship has not changed. If children lose respect for their elders and disregard the sanctity of the family, the whole society will be imperiled and disintegrate. There is no substitute for parental love, no substitute for good neighborliness, no substitute for authority in those who have to govern.

If the media are always putting down and pulling down the leaders, if they act on the basis that no leader deserves to be taken at face value, but must be demolished by impugning his motives and character, and that no one knows better than media pundits, then you will have confusion and eventually disintegration. Their attacks may make good copy and increase sales but will make it difficult for society to work.

Good governance, even today, requires a balance between competing claims by upholding fundamental truths: that there is right and wrong, good and evil. We cannot abandon society to whatever the media or the Internet sends our way, good or bad. If everyone gets pornography on a satellite dish the size of a saucer, then the governments of the world have to do something about it or we will destroy our young and with them human civilization. Without maintaining a balance, no society has a future.

Gardels | Censorship, then, is the affirmation of community values?

Lee | I would put it in slightly stronger terms. It is community approval or disapproval. When I was a student in England, I used to read a little notice in the newspapers that so-and-so could not be invited to Buckingham Palace because he had been divorced. Now they bring women that are having extramarital affairs to Buckingham Palace.

A certain barrier has been brushed aside. But such social conventions and sanctions have an important function, to uphold standards in a community. If I want to copulate in my front yard, I cannot be allowed to say it is my own business. If everyone does it, the children would be brought up confused. So the government and society must say “stop it.” That is the value of social sanctions — they are a necessary way of making everyone understand that some kind of behavior is off limits.

MULTICULTURALISM AND AIR-CONDITIONING

Gardels | Looking back, what have been the key building blocks of Singapore?

Lee | We are not a homogeneous society. If we were like Japan, then many problems would not exist. But we are a conglomeration of people who were thrown together by the British, each seeking out a better life than the one he or she left behind.

Such a mixture of people — Indians, Chinese, Malays — needs to reach a social contract, if you will, of live and let live. Otherwise, there can be no common progress. If you want to beat the other fellow down and insist that he act like you and observe your taboos, then the whole place will come apart. A live-and-let-live contract is thus a social precondition.

Gardels | Anything else besides multicultural tolerance that enabled Singapore’s success?

“Air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history.”

Lee | Air conditioning. Air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history. It changed the nature of civilization by making development possible in the tropics.

Without air conditioning you can work only in the cool early morning hours or at dusk. The first thing I did upon becoming prime minister was to install air conditioners in buildings where the civil service worked. This was key to public efficiency.