One of the single most iconic silent films and certainly the most famous picture from the pre-feature era, A Trip to the Moon has been studied and discussed for over a century. Why is it so beloved and how did it drill down so deeply into our pop culture? That’s what we’re going to find out.

Seek out new life forms and new civilizations—and kill them.

Some films are famous for certain scenes. Many have lines of quotable dialogue. However, there is a very small and exclusive club of movies that are remembered and symbolized by a single image.

A face in the moon with a rocket in its eye. That image from A Trip to the Moon is so famous that it is instantly recognizable even to people who have never seen a single silent film. It has been referenced and imitated in everything from children’s books to music videos. Martin Scorsese’s 2011 film Hugo was built around the scene and its creator, Georges Méliès.

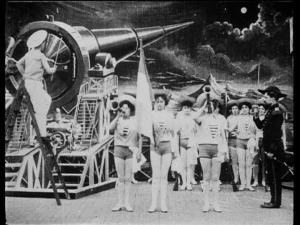

A Trip to the Moon is a mixture of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells (among other sources) all played with tongue in cheek. In a strange alternate Europe where the men wear wizard robes and the military is entirely staffed by women in hot pants, Professor Barbenfouillis (George Méliès) has come up with a mad plan. He intends to build a large, bullet-shaped metal capsule and fire himself to the moon with a giant cannon. His plan is dismissed as madness but five of his colleagues agree to accompany him.

The massive cannon is soon constructed, Barbenfouillis and company climb into their vessel and are shot at the moon. They hit the moon’s eye (it strikes me that I should start singing Dean Martin about now), disembark and start to explore.

The moon is as magical as Barbenfouillis had promised but the little party is soon set upon by the acrobatic Selenites, the native inhabitants of the moon. Barbenfouillis manages to kill their king with his umbrella and the scientists escape and climb back into the capsule. They make it back to earth and are feted for their adventures.

The story may seem simple to us today but it was quite an elaborate production for 1902. Keep in mind that projecting films for a paying audience was less than a decade old. The star and studio systems were in embryonic stages. Georges Méliès created magic in miniature, allowing his audience to ooo and aah and be thrilled for a few moments.

Also, further examination of the tale shows us that the story may not be as simple as we think. Film historian Matthew Solomon points out that Méliès 1890s political cartoons mocked militant nationalism and bullying colonialism. The whimsical path of destruction wrought by Barbenfouillis and his associates suddenly takes on disturbing real-world implications. It’s reasonable to conclude that Méliès was not celebrating the violent expedition to the moon; he was satirizing it.

Of course, if the social and political satire flies over the heads of modern viewers, we can at least take comfort in the fact that contemporary audiences also took the film at face value and simply enjoyed the fantastic adventures.

A Trip to the Moon was Méliès most ambitious production to date and it was an immediate hit with audiences. It also became one of the most pirated films in the young film industry. It was stolen, it was imitated and, ultimately, it was almost lost. Its recovery is one of the success stories of film preservation and part of the secret of its longevity.

Why do we remember it?

Thousands of short films were released during the first decade of commercial moviemaking. Out of those thousands, why is this film the one that has drilled deep into our consciousness? I am not in favor of dissecting this particular film down to its molecules (let’s preserve the magic) but here are a few thoughts on the subject.

It was extremely advanced for its time.

A motion picture with thirty scenes? That may not seem like much but it was quite ambitious in 1902. Further, Méliès was creating an entire fantasy planet to enchant his viewers. His investment of time and money paid off in worldwide enthusiasm for the film. Méliès himself saw little of the profits and only part of the acclaim. As mentioned before, the film was quickly pirated and passed off as the work of others.

In his essay Theatricality, Narrativity and Trickality, Andre Gaudreault writes that one aspect of A Trip to the Moon that often gets overlooked is its editing. Méliès employed extremely rapid editing by 1902 standards. In one case, he uses four shots in less than twenty seconds. Keep in mind that during this period, it was not unusual for films to be made up of a few lengthy scenes that played out without a single cut. Impressive.

I should also point out that Méliès embraced the theatricality of his sets and setting. His films wear their artificiality on their sleeve. (Do films have sleeves? Bear with me.) The painted sets and otherworldly costumes are not intended to fool or trick the audience. They exist to set the mood and they do an excellent job of it.

It can be boiled down to a single iconic image.

The man in the moon with a rocket in his eye. As mentioned before, this image is iconic. The concept of the man in the moon is familiar to the majority of audiences in Europe and North America (possibly in more places as well, I haven’t made study of it). Méliès took the concept and brought it to its logical conclusion. If the moon is a man’s face, it stands to reason that a spacecraft would be very irritating indeed.

The gentle humor and absurdist look at astronomy ended up creating the perfect formula for a memorable motion picture image.

It got just enough right to be seen as prescient.

Okay, so the moon doesn’t have acrobatic green men who disappear into puffs of candy-colored smoke when struck by umbrellas. You need a space suit and there are no maidens perched on stars. However, A Trip to the Moon’s rocket and cannon are not so terribly different from how the real trip to the moon occurred. Giving credit for artistic license and the time in which it was filmed, it did a pretty amazing job.

This prescient vision has led to some… interesting observations. One documentary on Méliès bizarrely brings up the “fake moon landing” conspiracy theory. “They could have faked the landing—like Melies! But he did it first! Nya nya nya!” That’s taking their admiration for their subject a little far, don’t you think? (Lunar truthers. Feh!)

It was an early target for preservation.

The talkie revolution hit in the late 1920s and silent films were seen as relics. Some were scavenged for footage to be glued into sound films. Some were destroyed. Some simply rotted away. Around the time that Al Jolsen was declaring that we ain’t seen nothing yet, interested parties in France were trying to track down and preserve the early history of film. In the case of Méliès, after the collapse of his studio, he destroyed his own body of work, burning hundreds of his own films.

He had not made a picture in years but Méliès was not without his champions. One of collectors of the past was Jean Acme Leroy. He obtained a partial print of A Trip to the Moon and upon his death, the Museum of Modern Art purchased his film collection. MoMA widely circulated the film (along with The Great Train Robbery) as an example of early narrative film and this is generally accepted to be the start of its revival outside of France.

Even in those dark times for lovers of silent cinema, A Trip to the Moon continued to gleam as one of the crown jewels of early film.

We are still in love with the dream.

We can be technical and go on and on about symbolism and technical marvels but the fact remains that all beloved films share an indescribable quality—shall we call it charisma?—that makes their audiences want to visit the world that they create.

Méliès set out to charm his audiences with painted sets and an unfettered imagination. His goal was simple but he succeeded in ways that would likely have astonished him. Over 110 years after A Trip to the Moon was released, most viewers would be hard-pressed to name major theater stars, composers, conductors, or even presidents and kings of 1902. But it seems that everyone knows that man in the moon with the rocket in his eye.

Movies are technical and they certainly can be subjected to academic examination. However, as I mentioned before, digging too deeply into the technical can kill the dream. In the end, I suppose the best answer is to say that we love it because it is wondrous.

A Trip to the Moon, in color

Movies had been in color since almost the beginning. In the case of Méliès, certain films were meticulously colored by hand. A Trip to the Moon was one of these films. (Méliès painted his sets in black and white, assuring that they would film well on the primitive nitrate.) When interest in this magician of early cinema was rekindled, the copies of A Trip to the Moon were battered, damaged, incomplete and in black and white.

Fortunately, a color print showed up in Spain. After years of painstaking restoration (the film was so badly decayed that it had fused into a solid mass), A Trip to the Moon was finally available with its original colors.

The Extraordinary Voyage, the 2011 documentary that accompanies that home media release of A Trip to the Moon, shows how the restoration was achieved and how a combination of old-fashioned film work and the latest technology joined forces to save a movie that would otherwise have been lost.

And now we come to something even more controversial than fake moon landings: silent film scores. There is nothing that silent film fans will argue about more (well, that and projection speed) than whether or not a score is suitable. Period music only! No synthesizers!

Just so you know where I stand, I am very much in favor of modernized scores. Within reason, of course. But I do like films scores that at least acknowledge that Prokofiev happened.

I say all this because A Trip to the Moon has a non-traditional score by the French electronica-ish duo Air. This score was met with derision is some circles but I quite liked it. So there.

I enjoyed hearing the thoughts of the band members, which were included as an extra on the DVD/Blu-ray release. Air respected the film enormously but they did not want to be stuck in another time. They stated that they had no wish to be forgers, that is, replicating the sounds of 1902 exactly. Rather, they wanted to include nods to the old days but make the score modern.

I subscribe to the belief that music is as important as the images on the screen. So when a score is said to “draw attention to itself,” that is not a bad thing in my book. A great many iconic sound film scores (Lawrence of Arabia; Star Wars; Alexander Nevsky; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; Yojimbo; The Elephant Man) do draw attention to themselves but they also support and harmonize with the images on the screen.

That being said, a lot of modern bands have made a bad name for themselves by treating silent films as free music videos. For example, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a rather tedious fad of allowing goth metal bands to play their existing songs over horror classics like Nosferatu and The Phantom of the Opera. In that case, the music is no longer an equal partner, it is an obnoxious interloper.

But let’s say we are not dealing with the heavy metal crowd. Let’s say that we are hiring a jazz, electronica or cabaret act. What then? Often, the problem with hiring bands for silent film scores is that they have no experience in movie music of any kind, aside from contributing a song to a compilation soundtrack. Stating the obvious but writing a film score is very different from writing a 2-5 minute song. Air had written and performed the acclaimed score for The Virgin Suicides (1999) so they were in a much better position to understand the needs of a silent film than many of their brethren.

For a band to succeed, respect for the film that they have been engaged to accompany is a must. Air clearly has that respect. Their style may not be for everyone but it suits me just fine.

***

A Trip to the Moon is an iconic silent film and probably the single most famous motion picture of the decade of the 1900s. It is also a window into a simpler age when it seemed that anything was possible in the movies. All I can say is that you really should see it for yourself.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, the cited essays can be found in the anthology Fantastic Voyages of the Cinematic Imagination: Georges Méliès’s Trip to the Moon. The book comes very highly recommended as a serious and scholarly dissection of this famous film, though it does occasionally become bogged down in its own jargon and does that kill-the-magic thing I have been talking about.

Movies Silently’s Score: ★★★★★

Where can I see it?

There are a lot of different editions floating around but I will restrict the discussion to high quality releases. The restored color version of A Trip to the Moon was released on DVD and Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. The release also includes an interview with Air, a documentary on Méliès and the restoration of the color film. It also contains the more familiar black and white version of the film with multiple score options. It really is the one to get for fans and film buffs.

The black and white version of A Trip to the Moon was also included in the Georges Melies: First Wizard of Cinema box set and the The Movies Begin: A Treasury of Early Cinema

box set. The Méliès disc from the latter release is also available as a stand-alone item

.

Great job of discussing a great film. This was the movie that made me want to start my own project to discover the cinema of an earlier era.

Thank you! It really is a magical film.

Beautiful review. Nice, too, that you mentioned HUGO, which is one of my all-time favorite movies *about* movies, right up there with CINEMA PARADISO.

Thank you! I have met a lot of newer silent fans who were introduced through Hugo.

That was a good survey of the movie and its importance, Fritzi. I think one of the first things that got me excited about searching on the web was finding a page on the Trip to the Moon operetta and the attraction at Coney Island’s Luna Park. I didn’t remember encountering them in film history books.

That is intriguing. Cross-promotion is much older than people think.

This is a terrific review for all sorts of reasons. However, there is one typo, the name should be spelled “H. G. Wells” not “Welles” as in “Orson Welles.”

Cecil B. DeMille and I have one major thing in common: neither one of us ever could spell 😉

Lovely to read your comments on this iconic film! It was one of the films that first triggered my interest in silent movies, so it will always be fondly remembered by me. On a slightly different note, when you mentioned the music in silent films, this reminded me of the showing of an early silent Hitchcock film, Champagne, made when he was still in the UK. I didn’t get the chance to see it in person, as it was broadcast in a cinema in London (too far away for me!), but the organisers had the great idea of streaming it live online and not showing just the film, but also the buildup to it (ie the audience arriving and taking their seats). The music was provided by an all-female quartet who incorporated modern songs into the score – for instance, Madonna’s “Poppa don’t Preach” when the heroine was being told off by her father. I wasn’t sure about this at first, but it did start to grow on me after a while and I found it quite witty. Another nice touch was that all four performers turned up at the cinema wearing matching 20’s flapper dresses, so they really got into the spirit of things!

You hit on the real secret to success for a non-traditional score: respect for the material. It sounds like the quartet tried to get into the spirit of things and put thought into their selections.

Oh, this film is a classic. The effects might seem crude by today’s standards but this was revolutionary when it came out, and in that sense it’s still impressive especially when you consider what other filmmakers were doing at the time (the Lumière bros., for example).

Yes, it was incredibly ambitious.

Most of this film also appeared in the 1956 version of Around the world in 80 days.

I haven’t seen that one in a long time. I seem to recall it was a great cure for insomnia.

It is, though at least they don’t give snide commentary when they show some of the Melies clip.

I love this film! The Hugo book was, along with my discovery of Clara Bow, what really introduced me to the world of silents – and Méliès.

Hurrah!

Excellent review of a cinematic cornerstone. But I’m curious about the black and white version that I’ve seen broadcast several times on TCM, the one with the clumsy (and completely unnecessary) spoken narration that supposedly was based on something Melies intended to be used with the film. Do you know what the story is on that aspect, the “narration,” of the film?

I also find the narration to be clunky but it seems that it was reasonably common during this period (check out “The Sounds of Early Cinema” for details). Films were accompanied by narrators or entire troupes of actors, depending on the exhibitor.

In Japan, silents films were usually narrated too. It’s weird, but I think with better writing and immersion, it could be kinda cool.

The benshi in Japan really made the narration an art, trilling their R’s for criminals, raising their pitch for ladies, speaking from the stomach for lords, etc. I think the main problem with A Trip to the Moon’s narration is that it really doesn’t add to the action on the screen. Is better delivery the answer, I wonder?