Abstract

Osteoporosis, through its association with fragility fracture, is a major public health problem, costing an estimated $34.8 billion worldwide per annum. With projected demographic changes, the burden looks set to grow. Therefore, the prevention of osteoporosis, as well as its identification and treatment once established, are becoming increasingly important. Osteoporosis is secondary when a drug, disease or deficiency is the underlying cause. Glucocorticoids, hypogonadism, alcohol abuse and malnutrition are among the most frequently recognized causes of secondary osteoporosis but the list of implicated diseases and drugs is growing and some of the more recently recognized associations, such as those with haematological conditions and acid-suppressing medications, are less well publicized. In some cases, advancement in treatment of the primary disease has led to people living long enough to develop secondary osteoporosis; for example, successful treatment for breast and prostate malignancies by hormonal manipulation, improved survival in HIV with the advent of anti-retroviral therapies, and improved treatment for cystic fibrosis. This Review emphasizes the importance of secondary osteoporosis, discusses familiar and less well-known causes and what is known of their mechanisms, provides guidance as to the pragmatic identification of secondary osteoporosis and summarizes treatment options, where available.

Key Points

Osteoporosis and associated fragility fractures are major public health problems, but once fractures develop, it is already too late; thus, prevention is a priority

A growing number of diseases, deficiencies and drugs are recognised as causing secondary osteoporosis, and should be suspected as causes in particular among men and pre-menopausal women presenting with osteoporosis

In most cases, the general principle of treatment of secondary osteoporosis is to treat the underlying disease or deficiency, or to remove the relevant drug

Mechanisms of secondary osteoporosis vary and include low bone mass, increasing falls, and reduced bone quality—treatment strategies might need to be adapted for different patients

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Office of the Surgeon General (US). The frequency of bone disease in Bone health and Osteoporosis: a Report of the Surgeon General. (US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, USA, 2004).

British Orthopaedic Association. The Care of Patients with Fragility Fracture. (British Orthopaedic Association, UK, 2007).

Harvey, N., Dennison, E. & Cooper, C. Osteoporosis: impact on health and economics. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 99–105 (2010).

Ross, P. D., Davis, J. W., Epstein, R. S., Wasnich, R. D. Pre-existing fractures and bone mass predict vertebral fracture incidence in women. Ann. Intern. Med. 114, 919–923 (1991).

Lindsay, R. et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA 285, 320–323 (2001).

Cuddihy, M. T., Gabriel, S. E., Crowson, C. S., O'Fallon, W. M. & Melton, L. J. III. Forearm fractures as predictors of subsequent osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis Int. 9, 469–475 (1999).

Deutschmann, H. A. et al. Search for occult secondary osteoporosis: impact of identified possible risk factors on bone mineral density. J. Int. Med. 252, 389–397 (2002).

Caplan, G. A., Scane, A. C. & Francis, R. M. Pathogenesis of vertebral crush fractures in women. J. R. Soc. Med. 87, 200–202 (1994).

Odabasi, E., Turan, M., Tekbas, F. & Kutlu, M. Evaluation of secondary causes that may lead to bone loss in women with osteoporosis: a retrospective study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 279, 863–867 (2009).

Moreira Kulak, C. A. et al. Osteoporosis and low bone mass in premenopausal and perimenopausal women. Endocr. Pract. 6, 296–304 (2000).

Tannenbaum, C. et al. Yield of laboratory testing to identify secondary contributors to osteoporosis in otherwise healthy women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 4431–4437 (2002).

Peris, P. et al. Clinical characteristics and etiologic factors of premenopausal osteoporosis in a group of Spanish women. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 32, 64–70 (2002).

Cerdá Gabaroi, D. et al. Search for hidden secondary causes in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause 17, 135–139 (2010).

Baillie, S. P., Davison, C. E., Johnson, F. J. & Francis, R. M. Pathogenesis of vertebral crush fractures in men. Age Ageing 21, 139–141 (1992).

Khosla, S., Lufkin, E. G., Hodgson, S. F., Fitzpatrick, L. A. & Melton, L. J. III. Epidemiology and clinical features of osteoporosis in young individuals. Bone 15, 551–555 (1994).

Poór, G., Atkinson, E. J., O'Fallon, W. M. & Melton, L. J. III. Predictors of hip fractures in elderly men. J. Bone Miner. Res. 10, 1900–1907 (1995).

Kelepouris, N., Harper, K. D., Gannon, F., Kaplan, F. S. & Haddad, J. G. Severe osteoporosis in men. Ann. Intern. Med. 123, 452–460 (1995).

Grisso, J. A. et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in men. Hip Fracture Study Group. Am. J. Epidemiol. 145, 786–793 (1997).

Scane, A. C. et al. Case–control study if the pathogenesis and sequelae of symptomatic vertebral fractures in men. Osteoporos. Int. 9, 91–97 (1999).

Evans, S. F. & Davie, M. W. Vertebral fractures and bone mineral density in idiopathic, secondary and corticosteroid associated osteoporosis in men. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59, 269–275 (2000).

Tuck, S. P., Raj, N. & Summers, J. D. Is distal forearm fracture in men due to osteoporosis? Osteoporos. Int. 13, 630–636 (2002).

Pye, S. R. et al. Frequency and causes of osteoporosis in men. Rheumatology (Oxford) 42, 811–812 (2003).

Ryan, C. S., Petkov, V. I. & Adler, R. A. Osteoporosis in men: the value of laboratory testing. Osteoporosis Int. 22, 1845–1853 (2011).

Brown, S. E. Rethinking “primary” osteoporosis: isn't all osteoporosis really just “secondary” osteoporosis? Better Bones [online] (2012).

Romagnoli, E. et al. Secondary osteoporosis in men and women: clinical challenge of an unresolved issue. J. Rheumatol. 38, 1671–1679 (2011).

Gallagher, J. C. & Sai, A. J. Is screening for secondary causes of osteoporosis worthwhile? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 6, 360–362 (2010).

Rubin, M. R. et al. Idiopathic osteoporosis in premenopausal women. Osteoporosis Int. 16, 526–533 (2005).

Dent, C. E. & Friedman, M. Idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis. Q. J. Med. 34, 177–210 (1965).

Rauch, F. & Bishop, N. Juvenile osteoporosis in Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, (ed. Rosen, C. J.) 264–267 (American Society for Bone Mineral Research, Washington, USA, 2008).

Brodsky, B. & Baum, J. Modelling collagen diseases: Structural biology. Nature 453, 998–999 (2008).

Sillence, D. O., Senn, A. & Danks, D. M. Genetic heterogeneity in Osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Med. Genet. 16, 101–116 (1979).

Marini, J. C., Cabral, W. A. & Barnes, A. M. Null mutations in LEPRE1 and CRTAP cause severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Cell Tissue Res. 339, 59–70 (2010).

Phillipi, C. A., Remmington, T. & Steiner, R. D. Bisphosphonate therapy for Osteogenesis imperfecta. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 4, Art. No.:CD005088. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005088.pub2.

Adami, S. et al. Intravenous neridronate in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 126–130 (2003).

Sakkers, R. et al. Skeletal effects and functional outcome with olpadronate in children with Osteogenesis imperfecta: a 2-year randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 363, 1427–1431 (2004).

Letocha, A. D. et al. Controlled trial of pamidronate in children with types III and IV Osteogenesis imperfecta confirms vertebral gains but not short-term functional improvement. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 977–986 (2005).

Ward, L. M. et al. Alendronate for the treatment of pediatric osteogenesis imperfecta: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 355–364. (2011).

Papapoulos, S. E. & Cremers, S. C. Prolonged bisphosphonate release after treatment in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 356 1075–1076 (2007).

Buntain, H. M. et al. Controlled longitudinal study of bone mass accrual in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 61, 146–154 (2006).

Haworth, C. S. et al. A prospective study of change in bone mineral density over one year in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 57, 719–723 (2002).

Bhudhikanok, G. S. et al. Bone acquisition and loss in children and adults with cystic fibrosis: a longitudinal study. J. Paediatr. 133, 18–27 (1998).

Haworth, C. S. Impact of cystic fibrosis on bone health. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 16, 616–622 (2010).

Sermet-Gaudelaus, I. et al. Low bone mineral density in young children with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175, 951–957 (2007).

Dif, F. et al. Severe osteopenia in CTFR-null mice. Bone 35, 595–603 (2004).

Shead, E. F. et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is expressed in human bone. Thorax 62, 650–651 (2007).

Wolfenden, L. L. et al. Vitamin D and bone health in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Endocrinol. 69, 374–381 (2008).

Papaioannou, A. et al. Alendronate once weekly for the prevention and treatment of bone loss in Canadian adult Cystic fibrosis patients (CFOS trial). Chest 134, 794–800 (2008).

Aris, R. M. et al. Efficacy of alendronate in adults with cystic fibrosis with low bone density. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 77–82 (2004).

Chapman, I. et al. Intravenous Zoledronate improves bone density in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Endocrinol. 70, 838–846 (2009).

Haworth, C. S. et al. Effect of intravenous pamidronate on bone mineral density in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 56, 314–316 (2001).

Bojesen, A. et al. Bone mineral density in Klinefelter syndrome is reduced and primarily determined by muscle strength and resorptive markers but not directly by testosterone. Osteoporosis Int. 22, 1441–1450 (2011).

Swerdlow, A. J., Higgins, C. D., Schoemaker, M. J., Wright, A. F. & Jacobs, P. A. Mortality in patients with Klinefelter syndrome in Britain: a cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 6516–6522 (2005).

Ferlin, A., Schipilliti, M. & Foresta, C. Bone density and risk of osteoporosis in Klinefelter syndrome. Acta Paediatrica 100, 878–884 (2011).

Ferlin, A. et al. Bone mass in subjects with Klinefelter syndrome: role of testosterone levels and androgen receptor gene CAG polymorphism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, E739–E745 (2011).

Eastell, R. et al. A UK Consensus Group on management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: an update. J. Intern. Med. 244, 271–292 (1998).

Kanis, J. A. et al. A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 893–899 (2004).

Weinstein, R. S. Glucocorticoid-induced bone disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 62–70 (2011).

Hofbauer, L. C., Hamann, C. & Ebeling, P. Approach to the patient with secondary osteoporosis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 162, 1009–1020 (2010).

O'Brien, C. A. et al. Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoblasts and osteocytes to induce their apoptosis and reduce bone formation and strength. Endocrinology 145, 1835–1841 (2004).

Weinstein, R. S. Glucocorticoids, osteocytes, and skeletal fragility: the role of bone vascularity. Bone 46, 564–570 (2010).

Russcher, H. et al. Two polymorphisms in the glucocorticoid receptor gene directly affect glucocorticoid-regulated gene expression. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 5804–5810 (2005).

Van Staa, T. P., Leufkens, H. G., Abenhaim, L., Zhang, B. & Cooper, C. Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. June, 2000. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 1487–1494 (2005).

Van Staa, T. P., Leufkens, H. G. M., Abenhaim, L., Zhang, B. & Cooper, C. Oral corticosteroids and fracture risk: relationship to daily and cumulative doses. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39, 1383–1389 (2000).

Van Staa, T. P., Leufkens, H. G. M., Cooper, C. Use of inhaled corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 581–588 (2001).

Cooper, M. S. et al. Osteoblastic 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type I activity increases with age and glucocorticoid exposure. J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 979–986 (2002).

Bone and Tooth Society of Great Britain, National Osteoporosis Society & Royal College of Physicians. Guidelines on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Royal College of Physicians [online]. (2003).

Grossman, J. M. et al. American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res. 62, 1515–1526 (2010).

Reid, D. M. et al. Zoledronic acid and risedronate in the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (HORIZON): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 373, 1253–1263 (2009).

Mok, C. C. et al. Extended report: Raloxifene for prevention of glucocorticoid-induced bone loss: a 12-month randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 778–784 (2011).

Saag, K. G. et al. Effects of teriparatide versus alendronate for treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: thirty six month results of a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 3346–3355 (2009).

Lau, A. N. & Adachi, J. D. Role of teriparatide in treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 6, 497–503 (2010).

Devogelaer, J. P. et al. Baseline glucocorticoid dose and bone mineral density response with teriparatide or alendronate therapy in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J. Rheumatol. 37, 141–148 (2010).

Saag, K. G. et al. Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2028–2039 (2007).

Bassett, J. H. et al. Thyroid status during skeletal development determines adult bone structure and mineralization. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1893–1904 (2007).

Cooper, M. S., Gittoes & N. J. L. Bone health and thyroid disease. Osteoporosis Rev. 18, 1–6 (2010).

Cummings, S. R., Nevitt, M. C. & Browner, W. S. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 767–773 (1995).

Bauer, D. C., Ettinger, B., Nevitt, M. C. & Stone, K. L. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Risk for fracture in women with low serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone. Ann. Intern. Med. 134, 561–568 (2001).

Flynn, R. W. et al. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration and morbidity from cardiovascular disease and fractures in patients on long-term thyroxine therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 186–193 (2010).

Turner, M. R. et al. Levothyroxine dose and risk of fractures in older adults: nested case–control study. BMJ 342, d2238 (2011).

Nicodemus, K. K. & Folsom, A. R. Iowa Women's Health Study. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes and incident hip fractures in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care. 24, 1192–1197 (2001).

Hofbauer, L. C., Brucck, C. C., Singh, S. K. & Dobnig, H. Osteoporosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 1317–1328 (2007).

Thrailkill, K. M., Lumpkin, C. K. Jr, Bunn, R. C., Kemp, S. F. & Fowkles, J. L. Is insulin an anabolic agent in bone? Dissecting the diabetic bone for clues. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 289, E735–E745 (2005).

De Liefde, I. I. et al. Bone mineral density and fracture risk in type II diabetes mellitus: the Rotterdam study. Osteoporosis Int. 16, 1713–1720 (2005).

Holst, J. J. et al. Regulation of glucagon secretion by incretins. Diabetes Obes Metab. 13, 89–94 (2011).

Venken, K., Boonen, S., Bouillon, R. & Vanderschueren, D. Gonadal steroids 117–123 in Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. (American Society of Bone Mineral Research, USA, 2008).

Shahinian, V. B., Kuo, Y. F., Freeman, J. L. & Goodwin, J. S. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 154–164 (2005).

Morgans, A. K. & Smith, M. R. RANKL-targeted therapies: the next frontier in the treatment of male osteoporosis. J. Osteoporos. http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/941310.

Smith, M. R. et al. Effects of Denosumab on bone mineral density in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 182, 2670–2675 (2009).

Fizazi, K. et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised double-blind study. Lancet 377, 813–822 (2011).

Ferrari-Lacraz, S. & Ferrari, S. Do RANKL inhibitors (denosumab) affect inflammation and immunity? Osteoporosis Int. 22, 435–446 (2011).

Cohen, S. B. et al. Denosumab treatment effects on structural damage, bone mineral density, and bone turnover in rheumatoid arthritis: a twelve month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1299–1309 (2008).

Geusens, P. P. et al. The ratio of circulating osteoprotegerin to RANKL in early rheumatoid arthritis predicts later joint destruction. Arthritis Rheum 54, 1772–1777 (2006).

Kong, Y. Y. et al. Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature 402, 304–309 (1999).

Wheater, G. et al. Suppression of bone turnover by B-cell depletion in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoporos. Int. 22, 3067–3072 (2011).

Lodder, M. C. et al. Bone mineral density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: relation between disease severity and low bone mineral density. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 1576–1580 (2004).

Diarra, D. et al. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodelling. Nat. Med. 13, 156–163 (2007).

Goldring, S. R. & Goldring, M. B. Eating bone or adding it: the wnt pathway decides. Nat. Med. 13, 133–134 (2007).

Goldring, S. R. Inflammation-induced bone loss in the rheumatic diseases. In Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases (ed. Rosen, C. J.) 272–275 (American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Washington, US, 2008).

Goldring, S. R. & Gravallese, E. M. Bisphosphonates: environmental protection for the joint? Arthritis Rheum. 50, 2044–2047 (2004).

Ali, T., Lam, D., Bronze, M. S. & Humphrey, M. B. Osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Med. 122, 599–604 (2009).

Compston, J. E. et al. Osteoporosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 28, 410–415 (1987).

Bernstein, C. N., Sargent, M. & Leslie, W. D. Serum osteoprotegerin is increased in Crohn's disease: a population-based case control study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 11, 325–330 (2005).

Moschen, A. R. et al. The RANKL/OPG system is activated in inflammatory bowel disease and relates to the state of bone loss. Gut 54, 479–487 (2005).

Bernstein, C. N., Leslie, W. D. & Leboff, M. S. AGA technical review on osteoporosis in gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 124, 795–841 (2003).

Henderson, S., Hoffman, N. & Prince, R. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effects of the bisphosphonates risedronate on bone mass in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101, 119–123 (2006).

Palomba, S. et al. Effectiveness of risedronate in osteoporotic postmenopausal women with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, parallel, open-label, two-year extension study. Menopause 15, 730–736 (2008).

Tebas, P. et al. Accelerated bone mineral loss in HIV-infected patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 14, F63–F67 (2000).

Moore, A. L. et al. Reduced bone mineral density in HIV-positive individuals. AIDS 15, 1731–1733 (2001).

Brown, T. T. & Qaqish, R. B. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS 20, 2165–2174 (2006).

Van Vonderen, M. G. et al. First line zidovudine/lamivudine/lopinavir/ritonavir leads to greater bone loss compared with nevirapine/lopinavir/ritonavir. AIDS 23, 1367–1376 (2009).

Bruera, D., Luna, N., David, D. O., Bergoglio, L. M. & Zamudio, J. Decreased bone mineral density in HIV-infected patients is independent of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 17, 1917–1923 (2003).

Mondy, K. et al. Longitudinal evolution of bone mineral density and bone markers in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36, 482–490 (2003).

Dolan, S. E., Kanter, J. R. & Grinspoon, S. Longitudinal analysis of bone density in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 2938–2945 (2006).

Fausto, A. et al. Potential predictive factors of osteoporosis in HIV-positive subjects. Bone 38, 893–897 (2006).

Cotter, E. J., Ip, H. S., Powderly, W. G. & Doran, P. P. Mechanism of HIV protein induced modulation of mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic differentiation. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 9, 33 (2008).

Fakruddin, J. M. & Laurence, J. HIV envelope gp120-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis via receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B ligand (RANKL) secretion and its modulation by certain HIV protease inhibitors through interferon-γ/RANKL cross-talk. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48251–48258 (2003).

Glesby, M. J. Bone disorders in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37 (Suppl 2), S91–S95 (2003).

Mallon, P. W. HIV and bone mineral density. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23, 1–8 (2010).

Lin, D. & Rieder, M. J. Interventions for the treatment of decreased bone mineral density associated with HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 2. Art No.:CD005645. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005645.pub2.

Callander, N. S. & Roodman, G. D. Myeloma bone disease. Semin. Haematol. 38, 276–285 (2001).

Melton, L. J. III, Kyle, R. A., Achenbach, S. J., Oberg, A. L. & Rajkumar, S. V. Fracture risk with multiple myeloma: a population-based study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 487–493 (2005).

Tian, E. et al. The role of the Wnt-signalling antagonist DKK1 in the development of osteolytic lesions in multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 2483–2494 (2003).

Morgan, G. J. et al. First-line treatment with zoledronic acid as compared with clodronic acid in multiple myeloma (MRC Myeloma IX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 376, 1989–1999 (2010).

Dore, R. K. The RANKL Pathway and Denosumab. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 37, 433–452 (2011).

Giuliani, N. et al. The proteosome inhibitor bortezomib affects osteoblast differentiation in vitro and in vivo in multiple myeloma patients. Blood 110, 334–338 (2007).

Vestergaard, P., Rejnmark, L. & Mosekilde, L. Proton pump inhibitors, Histamine H2 receptor antagonists, and other antacid medications and the risk of fracture. Calcif. Tissue Int. 79, 76–83 (2006).

Yang, Y.-X., Lewis, J. D., Epstein, S. & Metz, D. C. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA 296, 2947–2953 (2006).

O'Connell, M. B., Madden, D. M., Murray, A. M., Heaney, R. P. & Kerzner, L. J. Effects of proton pump inhibitors on calcium carbonate absorption in women: a randomized crossover trial. Am. J. Med. 120, 778–781 (2005).

Yu, E. W. et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of bone loss and fracture in postmenopausal women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 83, 251–259 (2008).

Coleman, R. E. et al. Skeletal effects of exemestane on bone mineral density, bone biomarkers, and fracture incidence in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer participating in the Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES): A randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 8, 119–127 (2007).

Llombart, A. et al. Immediate administration of Zoledronic acid reduces aromatase inhibitor associated bone loss in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: 12-month analysis of the E-Zo-FAST trial. Clin. Breast Cancer 12, 40–48 (2012).

Sergi, G. et al. Preventive effect of risedronate on bone loss and frailty fractures in elderly women trated with anastrozole for early breast cancer. J. Bone Miner. Metab. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00774-011-0341-1

Rizzoli, R. et al. Guidance for the prevention of bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women treated with aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer: an ESCEO position paper. Osteoporosis Int. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1870-0

Schwartz, A. V. et al. Thiazolinedione use and bone loss in older diabetic patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 91, 3349–3354 (2006).

Betteridge, D. J. Thiazolinediones and fracture risk in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 28, 759–771 (2011).

Lecka-Czerniik, B. Bone loss in diabetes: use of antidiabetic thiazolinediones and secondary osteoporosis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep, 8, 178–184 (2010).

Meier, C. et al. Use of thiazolinediones and fracture risk. Arch. Intern. Med. 168, 820–825 (2008).

Van Lierop, A. H. et al. Distinct effects of pioglitazone and metformin on circulating sclerostin and biochemical effects of bone turnover in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 166, 711–716 (2012).

Gustafson, B., Eliasson, B. & Smith, U. Thiazolinediones increase the wingless-type MMTV integration family (WNT) inhibitor Dickkopf-1 in adipocytes: a link with osteogenesis. Diabetologia 53, 536–540 (2010).

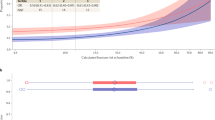

Kanis, J. A. et al. FRAX® and its applications to clinical practice. Bone 44, 734–743 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Studies of the estimated prevalence of secondary osteoporosis among women (DOC 69 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

Studies of the estimated prevalence of secondary osteoporosis among men (DOC 70 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walker-Bone, K. Recognizing and treating secondary osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 8, 480–492 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.93

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.93

This article is cited by

Osteosarcopenia predicts poor survival in patients with cirrhosis: a retrospective study

BMC Gastroenterology (2023)

A diagnostic predictive model for secondary osteoporosis in patients with fragility fracture: a retrospective cohort study in a tertiary care hospital

Archives of Osteoporosis (2023)

Use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of subsequent bone loss in a nationwide population-based cohort study

Scientific Reports (2021)

Occlusal disharmony-induced stress causes osteopenia of the lumbar vertebrae and long bones in mice

Scientific Reports (2018)

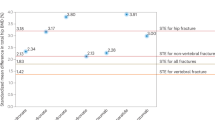

The Trabecular Bone Score (TBS) Complements DXA and the FRAX as a Fracture Risk Assessment Tool in Routine Clinical Practice

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2017)