Ten Intergroup Relations Films for the Current Era

Following the eruption of racial violence at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia on August 12, 2017, the 1943 US War Department film, Don’t Be a Sucker, went viral, suggesting that news outlets and social media users found its message to be newly relevant. Don’t Be a Sucker, which warns Americans of the perils of falling for divisive fascist rhetoric, was one of countless films, radio broadcasts, and television specials produced by governmental and civic organizations during the mid-twentieth century.

Together, these groups forged a loosely defined social movement around the concept of “intergroup relations.”[I] Flourishing between World War II and the 1960s, the intergroup relations movement aimed to combat not only the spread of fascist ideology, but also racism, religious intolerance, and other forms of prejudice. Although not without its flaws, the intergroup movement is worth reflecting on today as activists, political figures, and everyday Americans strategize ways to fight the latest resurgence of xenophobia, bigotry, and hate.

By way of an introduction to the movement, here are some key examples of intergroup relations films and broadcasts with relevance for the current political era.

Produced under the auspices of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ), this film tells the story of a thwarted attempt by Nazis to infiltrate the United States. Reflecting the intergroup movement’s breadth of focus, Greater Victory argues that immigrants are Americans, too, and ends with a display of inter-racial cooperation and tri-faith unity.

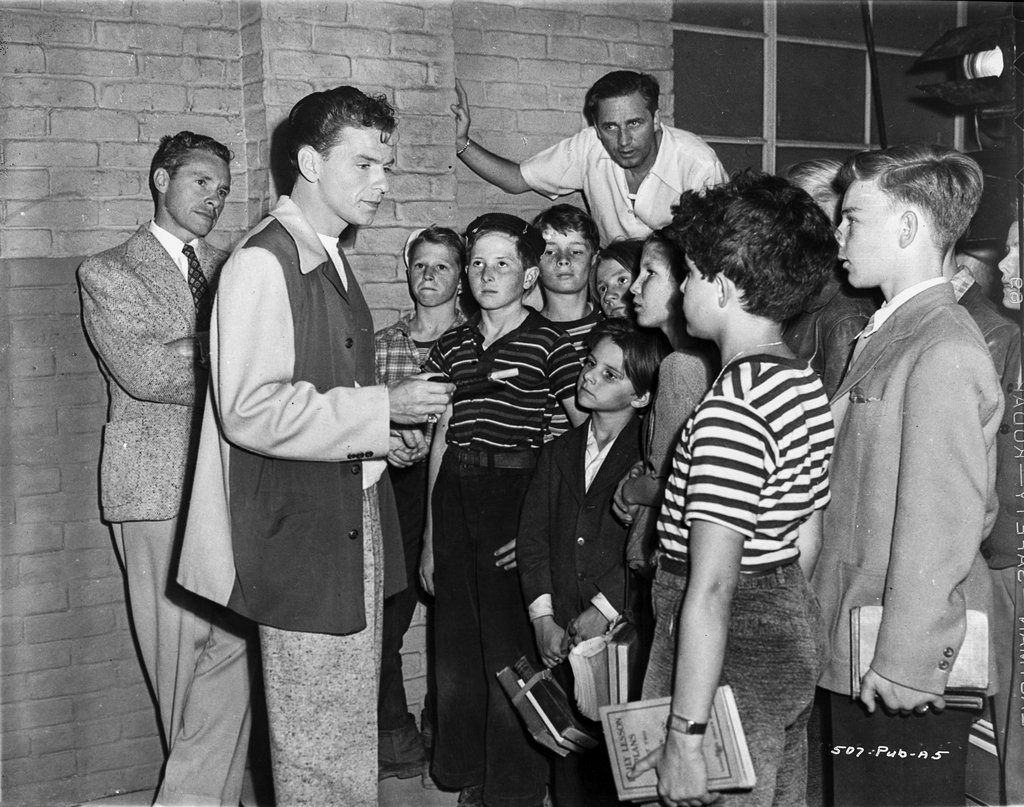

Written by Albert Maltz prior to his blacklisting as a member of the “Hollywood Ten,” this film features Frank Sinatra singing Abel Meeropol’s classic Popular Front anthem, “The House I live In.” In the film, Sinatra confronts a group of boys bullying a peer because of his religion. After comparing the boys’ actions to those of the Nazis and obliquely condemning the racial segregation of blood plasma by the Red Cross during the war, Sinatra treats the gang to an impromptu performance of Meeropol’s song.

Meeropol is also remembered for penning “Strange Fruit,” the haunting protest song made famous by Billie Holiday. An activist with ties to the CPUSA, Meeropol was a prominent and controversial figure on the Left. Notably, he and his wife adopted the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg following the couple’s execution for espionage in 1953. As an adaptation of Meeropol’s song, the film version of The House I Live In exemplifies the intergroup movement’s indebtedness to what Michael Denning calls “the cultural front” that flourished in the 1930s and 1940s.

Produced in Hollywood to promote the NCCJ’s American Brotherhood Campaign of 1946, The American Creed features a bevy of classic cinema stars including Ingrid Bergman, Eddie Cantor, Katharine Hepburn, and Jimmy Stewart speaking out in broad terms against disunity, intolerance, and hate. Discussing the film in 1955, NCCJ historian James Pitt, gushed, “the motion picture industry did this miracle for American Brotherhood in thirty days—producing, distributing, and exhibiting The American Creed to an applauding audience of 85 million people.”[II]

Sponsored by the United Auto Workers (UAW) and produced by United Productions of America (UPA), this animated film is an adaptation of anthropologists Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish’s pamphlet, “The Races of Mankind.” Brotherhood of Man uses “scientific anti-racism” to discredit the idea of white racial superiority. Organized labor leaders took an active interest in the intergroup movement during this era due to the outbreak of wildcat “hate strikes” by the white rank-and-file, who were concerned about the postwar implications of wartime integration. Brotherhood of Man was directed by UPA’s Robert Cannon; Ring Lardner and Maurice Rapf are credited as writers on the film, along with Phil “P.D.” Eastman. Like Maltz, Lardner and Rapf would later fall victim to the postwar Hollywood Red Scare. John Hubley was the film’s principal animator. During this time, he worked with both Eastman and Cannon at UPA, which later produced such animated classics as Gerald McBoing Boing (1950) and the “Mr. Magoo” cartoon shorts and TV series.

A series of 8 short films: Visit the AJC site directly to stream this series.

Produced under the auspices of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), these “anti-prejudice” animated shorts were distributed free of charge to television stations and circulated in 16mm format to schools, civic groups, and churches. Like Brotherhood of Man, each spot uses what is known as “limited animation,” a style of animation in which elements of frames are reused, giving the shorts their minimalist aesthetic. Each short explores a different scenario in which cooperation among members of different racial, ethnic, and religious groups is necessary for success. For example, in “Baseball,” members of the same team refuse to cooperate with one another. Only after overcoming their differences and working together is the team able to win the game. Tom Glazer provides folk music accompaniment, singing, “A nation’s like a baseball team / it’s run by teamwork too / And every race and every creed / works with Y- O- U! Play Ball!” As noted on the AJC’s website, a version of “Baseball” aired on television during the 1952 World Series.

Visit the AJC site directly to stream this film.

Produced under the auspices of The Civil Rights Association, The Challenge attempts the formidable task of dramatizing the Truman Administration’s 1947 report, To Secure These Rights: The Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights. Featuring a gumshoe reporter and female photographer, The Challenge begins as a film noir about a racially motivated murder. The murder and subsequent acquittal of the white perpetrators becomes one of several incidents that the reporter and photographer investigate in working on a story about civil rights in the United States. However, as they finish their work, the pair realize that their story is incomplete. A full account of the state of American civil rights needs to address not only violations against these rights, but also the progress being made towards greater social justice and equality. The reporter and photographer proceed to learn about the efforts being made by legislators, community organizers, educators, and labor leaders to curb discrimination and eradicate systemic inequality. Notably, The Challenge features both William Green, President of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), as well as Philip Murray, President of the Congress of Industrial Workers (CIO) prior to these organizations’ merger.

Produced by Dynamic Films and featuring a young Patty Duke in a supporting role, An American Girl tells the story of Norma, a white, Christian teenager who experiences social ostracization after she begins wearing a Jewish charm bracelet. The film connects Norma’s story to the larger context of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust through The Diary of Anne Frank, which Norma reads and which serves as inspiration for Norma’s own diary entries.

Produced by the Centron Corporation, a leading educational film company, What About Prejudice? tells the story of a group of teenagers who ostracize one of their peers, Bruce Jones. Bruce, who never appears fully onscreen, is different from the other high school students; however, the viewer never learns precisely how he is different. This was a common strategy of intergroup relations films, which aimed to convey the idea that all forms of bigotry, such as anti-Semitism and white racism, are manifestations of the same single social ill known as prejudice. What About Prejudice? was one of several films produced by the Centron Corporation as part of their “Discussion Problems in Group Living” series. These films addressed a range of issues affecting American youth, and were intended to be used as conversation-starters prompting discussion of the topics within small groups.

- Destiny’s Tot (Dir. Fielder Cook, 1960)

Visit the AJC site directly to view this film.

With its frank, psychoanalytic exploration of both same-sex and incestuous desire, Destiny’s Tot, directed by Fielder Cook, is one of the strangest films in the intergroup relations genre. Destiny’s Tot was produced in cooperation with the AJC and aired on NBC in 1960 before being distributed as an educational film. Featuring Robert Duvall as a fascist organizer imprisoned for treason during World War II, Destiny’s Tot is an adaptation of Robert Lindner’s Rebel Without a Cause: The Hypno-Analysis of a Criminal Psychopath. Like its source material, the broadcast uses Freudian theory to explore the psychological origins of the authoritarian personality.

Produced by the National Urban League (NUL), A Morning for Jimmy differs from the other films and broadcasts on this list by addressing African American teenagers rather than a presumed audience of white viewers. In keeping with the NUL’s focus on vocational guidance, A Morning for Jimmy suggests that through job training black youth can overcome not only encounters with prejudicial attitudes but also with discriminatory hiring practices. Although the NUL’s racial politics were moderate, during the 1960s the League would increasingly self-identify as a civil rights organization. A Morning for Jimmy is a pivotal film within the intergroup relations movement. As a production sponsored by a group with ties to both the intergroup and civil rights movements, the film points to the ways in which these two movements overlapped, as well as the fact that the civil rights movement largely displaced the intergroup movement as the 1960s progressed.

Header Image: On the set of The House I Live In (Mervyn LeRoy, 1945).

NOTES

Special thanks to the Internet Archive and the AJC Archives for doing the important work of preserving, digitizing, documenting, and making accessible these films.

[I] For more on the intergroup relations movement, see Stuart Svonkin, Jews Against Prejudice: American Jews and the Fight for Civil Liberties (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997). On the closely related tri-faith movement, see Kevin M. Schultz, Tri-Faith America: How Catholics and Jews Held Postwar America to Its Protestant Promise (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). For scholarship in film and media studies on the intergroup movement, see Anna McCarthy, “The Politics of Wooden Acting,” in The Citizen Machine: Governing by Television in 1950s America (New York: The New Press, 2010), 83-118.

[II] James E. Pitt, Adventures in Brotherhood (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Co., 1955), 99.

Copyright: © 2017 Film Quarterly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.