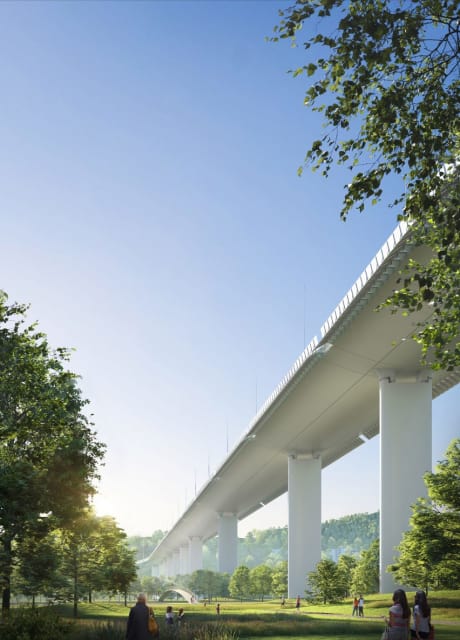

A rendering of Renzo Piano’s planned bridge, which will replace the collapsed Morandi Bridge. (Image courtesy of Renzo Piano.)

Five months after the deadly Genoa bridge collapse, the city has announced that it will replace the structure with another bridge that its designer claims will “last for a thousand years.”

On December 19, 2018, city mayor Marco Bucci announced a €202 million new bridge ($229 million) over the Polcevera River to replace the collapsed Morandi Bridge. The distinctive concrete bridge collapsed on August 15, killing 43 people and destroying many of the buildings underneath it. The reasons for the bridge’s collapse are still unknown.

The new bridge will be designed by architect Renzo Piano, who got his start as the codesigner of Paris’s CentrePompidou and more recently designed The Shard in London and the Whitney Museum in New York. Piano offered both his concept and his supervision on the project for free, calling it “an act of civic duty.”

Finishing the new bridge quickly is important for both residents and businesses in the city. Before its collapse, the Morandi was part of Genoa’s A10 motorway, an important link between Italy and France. In the wake of the collapse, the route has been closed off, and the city has been cut in half. "We want to solve a problem of infrastructure and mobility important not only for the city but also for the region, for this part of northern Italy, and I dare say, also for Switzerland and France," Bucci explained.

But amidst fears of another collapse, the construction team must manage a delicate balance between speed and quality.

Design

Piano’s design, which has far more piers and shorter spans than its doomed predecessor, also lacks that structure’s distinctive concrete stays. (Image courtesy of Renzo Piano.)

One of the possible culprits in the Morandi collapse was the bridge’s unusual design. Architect Riccardo Morandi was famous for his A-frame, cable-stayed bridges, which typically have very few stays per span (the Morandi Bridge, for example, had two). He also used both steel and concrete for his stays, coating steel cables with prestressed concrete.

The official investigation into the collapse is considering the theory that the cables in the southern stay broke, causing the bridge to become more unbalanced and more stays to break. In light of this possible explanation, the government-issued decree awarding the project mentioned that the bridge would need to be built with weight-bearing columns rather than stays “in respect for the psychological aversion that matured in the city after the collapse of the Morandi Bridge.”

Piano’s winning design is entirely stay less—it’s a simple white beam bridge supported by tall elliptical piers. The bridge features a continuous 1.1km (3,600ft) steel deck, with 20 spans and 19 reinforced concrete piers. In contrast, Morandi’s bridge had eight piers and nine spans, the longest of which was 690ft. The increased number of piers and shorter spans should give the new bridge more support than its predecessor.

The Morandi Bridge relied on a relatively small number of concrete-coated metal stays for its support. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Piano says that his bridge will “have elements of a boat because that is something from Genoa.” The piers look like the bow of a ship when viewed from the side, and the light from the lamps will be in the shape of a sail. The lamps also memorialize the tragic collapse; there will be 43 of them, one for each of the victims. Piano has called the bridge “very Genovese … [s]imple but not trivial.”

He has also emphasized how durable his design will be, saying in a recent interview with Dezeen that bridges “should be designed to last 1,000 years.” Piano believes such longevity is an achievable goal: “If you use steel, you add the right protection and you make every piece accessible, so that you can repair or repaint every five to 10 years."

Piano’s comment about accessibility is a direct reference to one of the flaws of the Morandi. Because its stays were made of metal coated in concrete, it was difficult to directly check whether they had corroded. One possible reason for the collapse is that insufficiently prestressed concrete could have let in water to erode the stays, quietly breaking the “backbone” of one of the spans without showing any external signs of damage.

Construction

One of the rumored reasons for the old bridge's collapse is potential mafia involvement in the construction process. Commentators have speculated that members of the mafia may have weakened the bridge by using sand-heavy concrete to cut costs. Whether or not this was a factor in the bridge's collapse, the construction process for its replacement will be under heavy scrutiny from the public.

The construction of the replacement bridge will be completed by Pergenova, a joint venture between infrastructure group Salini Impregilo and shipbuilder Fincantieri Infrastructure. Italferr, the consulting arm of the Italian railway state company, will handle the engineering tasks.

Salini Impregilo has built a total of 102 bridges over its 100-year lifespan, and the company has already collaborated with Piano on several concert halls. While Fincantieri doesn’t have the same kind of civil engineering experience, it will be focusing on the steel deck of the bridge.

An infographic shows the scale of the construction project. (Image courtesy of Fincantieri.)

The company plans to produce the components of the bridge spans in its Genoa-Sestieri shipyard and the company’s facility near Verona, and then transport them to the jobsite still in pieces. Onsite, the workers will weld together the pieces of each span while they are still on the ground, then lift the spans into place with strand jacks and a mobile crane.

What Next for the Bridge?

A rendering of the bridge from a farther distance gives a view of how it will look in the context of Genoa. (Image courtesy of Renzo Piano.)

While the three organizations involved in the project have ambitious plans, they won’t be able to get started on the construction work right away. Although the demolition work has started on the western half of the bridge, the ongoing investigation means that construction workers are still barred from the collapsed eastern end of the structure.

Currently, the bridge also faces possible legal challenges. Bridge operator Autostrade per l’Italia has been barred from participating in either the demolition or construction of the new bridge, as 20 of its employees are currently on trial for involuntary manslaughter for their possible role in the earlier bridge's collapse. The company has also been told that it must finance both the demolition and the construction. On December 28, Autostrade said that it had filed a complaint against the ban, claiming the restriction violated Italian law.

But despite the challenges, the Genovese have high hopes for their new bridge.

For Genoa, the rebuilding of the bridge isn’t just about reconnecting a divided city: it’s about creating a symbol of hope and progress in the city. The Morandi was a recognizable city icon, and its destruction tore a hole in the city. The hope is that Piano’s new bridge can replace it well.

“Twelve months to help relaunch Genoa,” said Pietro Salini, Salini Impregilo’s chief executive, during the mayor’s announcement about the new bridge. “That is the dream that we are hoping to give the Genoese before Christmas in memory of the victims of this terrible tragedy: to relaunch the city as quickly as possible and send a strong message to the entire country: Public works can kick-start the economy and start to create jobs again.”