- Art imitates life in the Master’s timeless tale of wartime espionage

- It plunges ordinary folk into exceptional, dangerous circumstances

- Polar opposites learn to unite and fight against a common enemy

- The Lady’s popularity endures, giving birth to numerous homages

- These include various spirited remakes and theatrical adaptations

- Screenplay by two British cinema legends led to spin-off film series

- Lady played by icon of London theatre and belated Hollywood star

- Source novel author’s works also adapted for other classic films

Note: this is one of 100-odd Hitchcock articles coming over the next few months. Any dead links are to those not yet published. Subscribe to the email list to be notified when new ones appear.

Part 1: Production and Ethel Lina White on home video | 2: Lady’s home video releases | 3: Soundtrack releases and remakes | 4: More “Vanishing Lady” films | 5: Similar train films

Contents

- Production

- More Ethel Lina White on home video

- The Unseen (1945)

- The Spiral Staircase (1946)

- Others

- Related articles

Production

“Superb, suspenseful, brilliantly funny, meticulously detailed entertainment” – Halliwell’s Film Guide

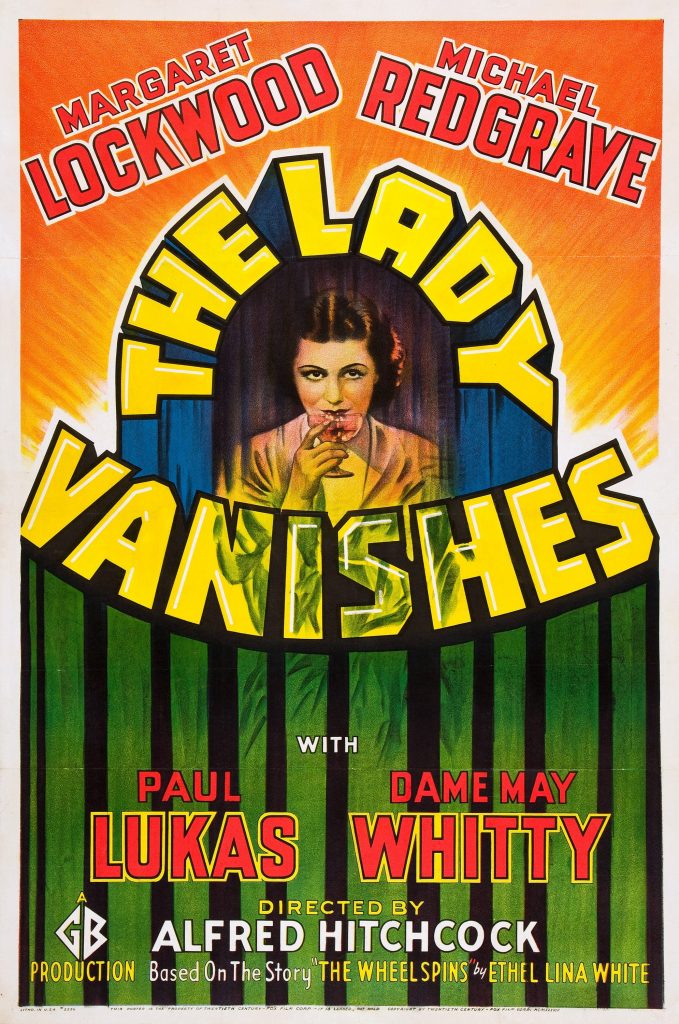

The star-studded comedy thriller that took the world by storm. The subtlety with which the humour of Miss Froy’s preposterous disappearance (played by the Splendid Dame May Whitty) gradually gives way to desperation and danger as the train carries the cast through Eastern Europe makes The Lady Vanishes a true Hitchcock masterpiece. Interestingly, it was Hitchcock’s last but one film in England for 10 years. Selznick invited him to Hollywood while The Lady Vanishes was in the making. – UK Rank LaserDisc (1982)

“Hitchcock’s mystery is directed with such skill and velocity that it has come to represent the quintessence of screen suspense.” – Pauline Kael

When an elderly lady mysteriously disappears on a train to London, a young woman embarks on a journey of intrigue,

danger and romance in this sparkling suspense classic. A search for her new friend, Miss Froy (the superb Dame May Whitty), soon embroils pretty young traveler, Iris (Margaret Lockwood) and fellow traveler Gilbert (Michael Redgrave) in the sinister shenanigans of an enemy spy ring. Considered among Hitchcock’s finest films, this brilliant comic-mystery rockets along with a first class script and top-notch performances from the most fascinating cast of characters since Grand Hotel. All aboard! – US Hallmark 4-VHS The Master of Intrigue (1995)

What to say? The Lady Vanishes completes Hitch’s famed sextet of 1930s thrillers and stands proud as one of his greatest works. Of all the Master’s British films, she’s perhaps only pipped to the post in popularity by The 39 Steps. Therefore, it seems only natural she should inspire a similar number of remakes, homages, spin-offs and finally, in 2019, not one but two comedic stage plays. The first to be performed, in the spring of that year, returns to the source novel for its framework, whereas the second, which premièred in the autumn, is based squarely on Hitch’s film. Said novel, The Wheel Spins (1936), was penned by Ethel Lina White though most copies have been retitled since the runaway success of its more famous cinematic offspring.

Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat were the pair of fast-rising writer-producer-directors responsible for the screenplay. It was originally meant for director Roy William Neill, who is perhaps best known for helming the lion’s share of the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes series. When production delays led to a scheduling conflict, Hitch came onboard, making Lady one of the few projects he joined when it was already in progress. Launder and Gilliat’s contribution to British cinema history is inestimable and they were responsible, in at least one guise or other, for over a hundred films, almost half of them jointly. But several in particular that feature their input are directly related to Lady. Firstly, her immediate progenitors are Rome Express and Seven Sinners, with Night Train to Munich (1940) her sequel in all but name. Gilliat co-wrote Hitch’s next outing, Jamaica Inn, while both men wrote, produced and directed the fantastic wartime flag-waver Millions Like Us, which saw the return of two major characters from Lady.

- Launder and Gilliat (1977) – Geoff Brown

Launder and Gilliat (2013) – Bruce Babington

L-R: Naunton Wayne, Margaret Lockwood, Dame May Whitty, Michael Redgrave, Basil Radford and Cecil Parker

Movie Locations: The Lady Vanishes

Unlike screenwriter Charles Bennett with Hitch’s preceding five films, Launder and Gilliat didn’t deviate too drastically from the novel. The chief changes they made were to drop a vicar and his wife, and replace a pair of sisters with two wholly new characters, namely Charters and Caldicott, played by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne respectively. This last especially was a masterstroke, as the popularity of the duo’s continuing adventures on film and radio over the ensuing 14 years will readily attest. In fact, their very appearance saw them on another wartime rail journey in Night Train to Munich. Radford, who also appeared in party scenes in both Young and Innocent and Jamaica Inn, was a veteran of the First World War, as attested by the scar on his right cheek.

Two other significant changes from White’s novel occur: the hapless Miss Froy, who is unwittingly drawn into the novel’s intrigue, is transformed in the screenplay into a knowing, active protagonist. Secondly, our heroine, Iris Henderson, has no romantic prospect whatsoever in the novel; neither a pending marriage nor even a prospective reconfigured matrimonial match at journey’s end. In that regard, Hitch’s Iris now has a much more complete and satisfying story arc. Iris provided the international break-out role for Margaret Lockwood, who had enjoyed a steadily ascending career in British plays and films over the previous five years, and would go on to become a mainstay of film and television for the next 35 before before withdrawing entirely from public life.

My Favourite Hitchcock: The Lady Vanishes – Jonathan Coe, The Guardian

Lady’s witty script is peppered with more bon mots and one-liners than you can shake a stick at, and you’ll also find Hitch’s most ephemeral MacGuffin to date. Spoiler: it’s a tune. Though even more slight than the “Air Ministry secrets” driving the plot of The 39 Steps, it well recalls the theme tune that led Hannay to cracking that mystery. The complete shooting script is reproduced in Masterworks of the British Cinema: Brief Encounter, Henry V , The Lady Vanishes (1990).

The Lady Vanishes – Joe Valdez

Dame May Whitty essays the part of Miss Froy, just one of many highlights in a tremendously successful seven-decade acting career lasting from her teens until just weeks before her death at the age of 82. Though she had long trodden the boards, including many roles in leading West End productions from 1890 onwards, her film début wasn’t until 1914 at the age of 49. In 1918, she became the first actress to receive a damehood. She went on to firmly establish herself in middle-aged lady character roles and from the late 1930s, having by then entered her 70s, notched up an extremely impressive tally of appearances in transatlantic stage and screen offerings. Thanks to the latter, to modern audiences she is perhaps equalled only by Margaret Rutherford in the dotty old spinster stakes. Living up to the spirit of her name, she once said, “I’ve got everything Betty Grable has… only I’ve had it longer.”

She brought both class and heart to many American classics, including Mrs. Miniver (1942), Lassie Come Home (1943), Madame Curie (1943) and Gaslight (1944). Other notable screen appearances included Hitch’s Suspicion and one he was originally due to have co-directed, Forever and a Day. Whitty and her husband, actor Ben Webster, were heirs to a theatrical dynasty and their daughter Margaret, a noted actor and stage director in her own right, penned the family history, The Same Only Different (1969). In 2004, she received her own long overdue biography, Margaret Webster: A Life in the Theater.

As with many Hitchcocks, the special effects are not always so very. But it’s all part of the plan, as explained by film scholar Maurice Yacowar, author of Hitchcock’s British Films (1977), in a paper for the 2023 HitchCon.

“Sometimes Hitchcock’s scenes of brazen falseness… tempt us to assume the Master has grown careless, sloppy, in admitting an obviously fake shot. For example, The Lady Vanishes opens on an obviously miniature setting. This isn’t just to save money. Rather, it’s a play with form, a register of pretending. It’s a visual equivalent to “Once upon a time…,” the traditional start of a folk tale like this. Of course, what “Once upon a time” really means is “Never” but also “Always.” It’s how Fiction trumps History.

The film shifts from this initial pastoral romance into hard political reality in the climactic gunfight with the Nazis. That movement of the film as a whole is also reflected in the two comic Brits’ byplay. The foppish cricket-nerds turn into warriors — and one proves a crack shot to boot.”

Spoilers ahead: Like Hitch himself, I’m averse to the over-analysis of films that ultimately says more about the interpreter than the work in question. But rich political commentary clearly runs through Lady. Its cast of international characters are obviously avatars for the various major European players of the 1930s, trudging down the path to inevitable disaster. The shadowy über antagonists of The 39 Steps, there referred to only as a “foreign power”, are here solidified into the fictitious European country of Bandrika. Both are clearly stand-ins for Nazi Germany, who couldn’t be named outright at the time for fear of upsetting international relations. To say nothing of the still-lucrative European cinema market. As in real life, until the final act, most have their own selfish interests at heart and they’re slow to wake up to the threat, but when they do, they act both bravely and decisively.

Film historian Charles Barr, writing in English Hitchcock (1999) provides an exceptionally insightful, thoroughly grounded analysis of the film. Among many keen observations, he notes that not only does it have two significant instances of life imitating art but is actually prescient in that regard. He and other commentators are oft apt to draw parallels with Cecil Parker’s spineless, ill-fated Todhunter (Tod is German for death) and his futile waving a white handkerchief in an attempt to appease attacking fascists as parodying Neville Chamberlain’s famous waving of the worthless peace treaty on his return from Munich. But shooting was completed several months before the Munich Agreement took place. Likewise with C&C’s constantly thwarted efforts to get home in time for the England versus Australia Test Match at Old Trafford, only to find… Well, let’s just say that in July 1938, that self-same tournament was abandoned due to persistent rain.

Ultimately, alongside The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes is quintessential British Hitchcock, and really needs no further recommendation. If you haven’t seen it yet, what on earth are you waiting for? Check out one of the many great quality releases now available.

My Favourite Hitchcock: The Lady Vanishes – Philip French, The Guardian

Anyone know who the on-set stills photographer was? They did a blooming good job; many of their beautiful compositions have a distinctly painterly quality and wouldn’t look out of place hanging next to Renaissance art. Rear: Cecil Parker, Linden “cheekbones to die for” Travers, Dame May Whitty, Margaret Lockwood; Front: Paul Lukas (prostrate), Naunton Wayne, Basil Radford, Michael Redgrave; the dark habit in the foreground is nun other than Catherine Lacey.

More Ethel Lina White on home video

Though a relatively prolific and hugely successful crime writer in her own time, most of White’s oeuvre has been long out of print and drifted into obscurity. The same fate has befallen many authors; witness another personal favourite, W. W. Jacobs, one of the best-selling – and best – British authors of the early 20th century. But few of his works, bar his short story “The Monkey’s Paw” have been adapted for the screen and he’s consequently all but forgotten. Works by such as these have often not dated at all and retain their power to entertain, educate and enlighten us. As is usually the case, regular adaptations in other media help keep the originals alive and relevant for modern audiences. Actually, I can’t think of any perennially popular literary endeavours that don’t have at least one high profile remake, long-running theatrical adaptation, or reimagining of some description and most of them have many. Here’s a round-up of all the big and small screen versions of White’s tales to date…

The Unseen (1945)

White’s 1942 novel Midnight House (US: Her Heart in Her Throat) was the basis for mystery thriller The Unseen (1945) and some reprints were renamed after the film. The screen version’s noir credentials were boosted further with a screenplay co-written by Raymond Chandler but it’s sadly so far officially unavailable on home video.

The Spiral Staircase (1946)

Poster by Nikos Bogris, 2018

Due to her newly raised profile, White’s earlier novel Some Must Watch (1933) was adapted for this dark, extremely Hitchcockian thriller. Again, many reprints of the novel have been renamed after the film. It was remade in 1975 and most recently as a TV movie in 2000.

The Story: A mute woman is stalked by a psychotic killer in this Hitchcockian Gothic thriller set in a turn-of-the-century New England town. Helen Capel (Dorothy McGuire) is a good-hearted young woman who has been unable to speak since she suffered a traumatic shock as a little girl. She now works as a servant in the sprawling Warren mansion, which is dominated by the cantankerous, bedridden family matriarch, Mrs. Warren (portrayed by Ethel Barrymore in a performance nominated for a 1946 Best Supporting Actress Oscar).

When the calm of the peaceful village is shattered by a bizarre murder spree, a pattern soon emerges: all of the victims are women with afflictions. Helen could well be next, and Mrs. Warren seems to feel she is in particular danger if she remains in her employ. The old woman’s stepson, Albert (George Brent), promises to protect Helen, but it might be too late. The killer has already gained entrance to the house. As a storm rages outside, the murderer is busy inside, stalking Helen from the shadows and laying the groundwork for a carefully planned trap, confident Helen will be easy prey because of her inability to speak. Co-starring Rhonda Fleming, Elsa Lanchester and Sara Allgood, skilfully directed by Robert Siodmak, and propelled by superb cinematography, The Spiral Staircase is a twisting tale of terror that works perfectly from beginning to end.

Behind the Scenes: The Spiral Staircase was adapted from the novel, Some Must Watch by Ethel Lina White. In the book, the heroine was crippled but the film’s producers decided a psycho-somatic mute would affect audiences more because she could not articulate her fears or scream for help. Performing without speaking isn’t easy, yet Dorothy McGuire makes every moment totally believable, whether she’s expressing happiness or terror. One reviewer observed that the audience with which he saw the film responded to McGuire’s performance with “frequent spasms of nervous giggling and… audible, breathless sighs.” Another effective element of the movie is its excellent camerawork, which captures the spirit of the story and helps create its high level of tension. Particularly eerie are the close-ups of the killer’s eye and the point of view shots before the murderer strikes. A finely tuned chiller, The Spiral Staircase is the perfect film for a moonless, windy night. – US CBS/Fox LD sleeve notes, (1992, LDDb)

“Anything can happen in the dark!” – Elsa Lanchester

Of those directors most closely associated with film now –Ray, Lang, Preminger et al. – Robert Siodmak remains the least appreciated, the most shadowy, perhaps the most truly noir. Although his career spanned four decades, from the 1920s to the late 60s, his reputation rests squarely on his output in the immediate post-war years, 1945-1950: the noir years. Born in Memphis, Tennessee to German-Jewish parents in 1900, Siodmak grew up in Germany. After a spell in business and in the theatre he got his start in the film industry as a title-writer and editor. In 1929 he made his directorial debut with the droll semi-documentary People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag), a silent film which also boasted the talents of writers Billy Wilder and Curt Siodmak (Robert’s brother) and co-directors Fred Zinnemann and Edgar G. Ulmer. All of these promising young film-makers were soon to flee Hitler’s Germany for Hollywood, Siodmak by way of Paris, where he worked between 1933 and 1940.

After a mixed bag of B-movies (Son of Dracula, Cobra Woman) Siodmak hit upon his forte with the moody now thriller Phantom Lady, starring Ella Raines and Franchot Tone. With its jagged, jutting compositions and barely suppressed nihilistic despair, Phantom Lady struck a balance between the feverish Germanic Expressionism the director clearly relished and the general air of war fatigue taking hold of his adopted country. More followed: Christmas Holiday (with Deanna Durbin marrying murderer Gene Kelly); The Suspect (Charles Laughton as a Crippen-type); Uncle Harry (George Sanders plans to murder his sister); The Dark Mirror (Olivia de Havilland as twins, one of them a psychopath); The Killers (Burt Lancaster awaiting death-by-flashback) and Cry of the City (Victor Mature tracking down his old friend, killer Richard Conte).

Released in 1946, The Spiral Staircase comes half-way through this spectacularly morbid, fruitful phase in Siodmak’s career. Although it’s not, strictly speaking, film noir, this old-dark-house mystery draws on the same fascination with violent psychosis and an atmosphere of fetid mistrust the director was coming to specialise in. What’s remarkable is how, liberated from the familiar claustrophobic city streets and murky menace of the crime film, Siodmak pushes these themes to new extremes. Like Fritz Lang’s similar sojourn in the country, House by the River, Spiral Staircase turns into a full-blown gothic horror: storm clouds gather, strange figures lurk in the shadows and skeletons start rattling in their cupboards. In this regard, the film can also be seen usefully in conjunction with another RKO production, Val Lewton’s Jane Eyre adaptation I Walked with a Zombie, as well as the Selznick-Hitchcock collaboration Rebecca – melodramas which anticipate Psycho by placing a vulnerable heroine in an outwardly respectable but inwardly diseased household. It seems only fair to add that while Spiral Staircase may lack the literary exoticism of the Lewton film and the fetishistic wit of the Hitchcock, its a sight more scary than either of them.

The opening, for example, is a virtuoso display of Siodmak’s visual elan. After sketching in period (1906) and place (small town New England) in a few brief strokes, the camera follows a couple of young boys as they sneak a glimpse through the curtains of a make-shift cinema (‘Motion Pictures – the wonder of the age’ reads the placard outside). We spy on a young lady (Dorothy McGuire), as she sits entranced by the silent melodrama played out before her, until the camera ascends to the hotel room above, where another woman is pulling on her nightgown, entirely ignorant of the unknown man hiding in the wardrobe. Gigantic close-ups of the voyeur’s eye are intercut with unsettlingly distorted point-of-view shots: the woman, headless, struggling into her gown, arms pulling up through the sleeves, then clenching in her death-throes. Cinema-voyeurism-perversion-death: Siodmak’s camera intimates a far more sophisticated psychological understanding than any of the pat Freudian explanations Mel Dinelli’s script will trot out. We’re three minutes into the movie, and like the film Ms McGuire is watching, its virtually a silent so far. Ironically, as we soon learn, McGuire too is silent, a mute traumatised by the death of her parents, and the next likely victim of a murderer with a special penchant for the impaired. The spiral staircase, you see, is a cycle of despair, the warped circuit of a twisted psyche.

Robert Siodmak continued to work irregularly after 1950, in Hollywood and on the continent, but never again with such concentrated purpose. The dark, dirty films at which he excelled went out of fashion, and those critics who might have championed his cause had bigger fish to fry. Nevertheless, when he passed on in 1973, Siodmak left a small, stunning cadre of work for which he will be remembered: he was one of those select film-makers who truly showed us that anything can happen in the dark. – Tom Charity, Eu Pioneer LD (1994)

There are many DVD bootlegs of this title from Italy (A&R Productions; Sinister Film/reissue), Germany (Crest Movies, Evolution, Laser Paradise; all the same company), Spain (Memory Screen/LaCasaParaCineDel Todos, Suevia/IDA Films), and others. There’s even a pirate Spanish BD-R from Blackfire Productions. Avoid them all; these are the only good quality, legit releases:

- US: Anchor Bay DVD (2000)

- MGM DVD (2005), also in 4 Horror Movies

- Kino BD and DVD (2018)

- UK: Fremantle DVD (2002, reissued 2007)

- Italy: Dall’Angelo Pictures DVD (2006)

- Sweden: Studio S DVD (2018) info

The 1975 version is a British production directed by Peter “The Italian Job” Collinson and with a transatlantic cast including Jacqueline Bisset, Christopher Plummer, John Phillip Law, Sam Wanamaker and Elaine Stritch. It’s been issued in the US on a Warner DVD (2012). It’s region 0, NTSC, so will play anywhere. The schlocky 2000 US TV remake hasn’t been released as yet but here’s its trailer.

Others

White’s novel Put Out the Light (1931) was the basis for an eponymous but sadly missing, final-season episode of Detective (1964–1969). Unfortunately, fewer than half of this BBC anthology TV series’ 45 episodes are known to survive and none are currently available for viewing.

Lastly for now, her 1939 short story “An Unlocked Window” was the basis of one of the most terrifying episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, due in no small part to being filmed in the house from Psycho. First published in the April 1934 issue of The Novel Magazine, it has since been anthologised in Murder at the Manor: Country House Mysteries (2016). It was revisited in 1985 as part of the pilot for the 1980s remake series but at the time of writing only the original version, featured in season three of Hour in 1965, is available on home video. However, if you’re in the US the latter can be viewed on NBC.

White’s final screen credit to date is for “Put Out the Light“, a 1969 episode of the three-season BBC TV Series Detective (1964–1969), based on her eponymous 1931 novel. Sadly, like so much missing-believed-wiped pre-1980s British TV, only 23 of its 45 episodes are known to survive, and this one is not among them.

Part 1: Production and Ethel Lina White on home video | 2: Lady’s home video releases | 3: Soundtrack releases and remakes | 4: More “Vanishing Lady” films | 5: Similar train films

Related articles

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: Setting the Scene

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: Miscellaneous British Films

- Free the Hitchcock 9! Releasing the BFI-Restored Silents on Home Video

- Bootlegs Galore: The Great Alfred Hitchcock Rip-off

- Alfred Hitchcock: Dial © for Copyright: British Law

- Hitchcock/Truffaut: The Men Who Knew So Much

- Alma Reville: The Power Behind Hitchcock’s Throne

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: The British Years in Print

- Alfred Hitchcock: The Dark Side or the Wrong Man?

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: Miscellaneous Releases

- Beware of Pirates! How to Avoid Bootleg Blu-rays and DVDs

- Charlie Chaplin Collectors’ Guide, Part 2: The Bad, the Ugly and the Good

For more detailed specifications of official releases mentioned, check out the ever-useful DVDCompare. This article is regularly updated, so please leave a comment if you have any questions or suggestions.

Note: The Spiral Staircase is on Kino’s “While Supplies Last” list, which means when it sells out, it will be out of print.

Under your section on The Spiral Staircase… speaking of Val Lewton and anticipations of Psycho, check out The Seventh Victim for a proto-Psycho shower scene!