Protestantism

in the Scandinavian countries

At the beginning of the XVIth century, Scandinavia consisted of two kingdoms : one was made up of Norway and Denmark and the other Sweden and Finland. They both loosely belonged to the same confederation (the Union of Kalmar) which disintegrated at the time of the Reform movement. Lutheranism soon became the main religion and this favoured the constitution of national Churches which could each retain the use of its own language – they were all under State control. Today, even if the churches are not full, the influence of Lutheranism can still be deeply felt in the life of these countries.

Denmark

Lutheranism was introduced by Hans Tausen (1494-1561), a former monk who had been a student of Luther’s in Wittenberg. It took hold in 1523 in the reign of Frederic Ist (1523-1533) : the Diet of Odensee proclaimed religious and political freedom from Rome. In 1530, a specifically Lutheran confession of faith (asserting the importance of justification by faith) was taken up by the king (Confession Hafniensis). However it was in the reign of his son, king Chiristian III (1534-1559) that the main principles of the Lutheran Reformation movement were officially imposed on the population ; in this way the national religion of Denmark became Lutheranism. In 1537, (Diet of Copenhagen) a new liturgy written in Danish replacing the previous one ; any catholic bishops who refused to convert to Lutheranism were dismissed and replaced by others chosen by Johannes Bugenhagen (1485-1558), a friend of Luther’s, a pastor in Wittemberg and the main organizer of the first Lutheran Churches in the Scandinavian countries. The possessions and convents of the Catholic Church were redistributed to the Lutheran Church, which established a synodal system of government. A consistory provided the necessary links between the Churches and the king. The university of Copenhagen became Lutheran. The Bible was translated into Danish in 1550. Official Protestantism in Denmark, as in the other Scandinavian countries, was built on the same lines as the German model : a main body of regional protestant states, each under the control of its prince. In 1559 Frederic II came to the throne ; he was a conservative king who had little sympathy for protestants who were not Lutherans ; he refused to welcome reformed refugees from the Spanish Low Countries who had been persecuted by the duke of Alba. He and his subjects remained loyal to the Confession of Augsburg so his country was largely spared the terrible conflicts which existed in Germany due to the increase in reformed Protestantism.

Christian IV (1588-1648) succeeded in 1596. He followed in his father’s steps as a strict Lutheran : he forbade the Jesuits, who had become fervent supporters of the Counter-Reform movement, from entering Denmark and all catholic priests were banned.

However, he made a grave mistake : when he joined the Thirty Years war alongside the German protestants, his troops fared badly, leaving Sweden to emerge as the most powerful Scandinavian country at that time.

In the XVIIIth century, the pietistic movements came to Denmark but they did not have a negative impact on orthodox Lutheranism as it had become rather dry and intellectual by then. In the second part of the XVIIIth century rationalism had a great influence on the country (these ideas led to the establishment of sophisticated scientific institutions in Denmark) ; however by the beginning of the XIXth century it had declined in popularity. It was then that the revival movements had a large following ; they criticized the dependence of the Church on the State and in 1849 the Constitution voted a law in favour of complete religious freedom. Indeed, Church and State were closely linked ; the Constitution established that the Evangelical Lutheran Church should be the national Church of Denmark. Parliament was its legal authority and the Ministry of Church Affairs, its administrative authority. The moral aspect of the State’s support of the Church was catered for by the fact that the king had to be a member of the Church.

In 2005, out of 5.3 million inhabitants in Denmark, 85 per cent were Christian, 4.5 million of which belonged to the Lutheran evangelical Church. The other protestants and in particular, the Baptists played an active role but remained in the minority. Only one per cent of the population was Catholics ; however the situation has since changed due to the presence of many different cultural groups in the country, so the Churches will have to adapt to different circumstances.

There were several distinguished Danish protestants : the brilliant astronomer Thycoe Brahé (1546-1601), the writers Andersen and Karen Blixen ; perhaps the most famous protestant was the philosopher Soren Kirkegaard (1813-1855).

Webstie of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark (Folkekirkens mellemkirkelige Råd)

Norway

Norway was under Danish control. For this reason : Lutheranism was imposed on the country in 1537, according to the principle of Cujus regio, ejus religio, (the king imposed his own religion on his subjects). As in Denmark, the Catholics were banned and Danish replaced latin in the liturgy. However, the poorer parts of the population did not welcome these changes : indeed, they remained faithful to certain catholic traditions until the beginning of the XVIIth century. Due to this fact, Lutheranism only made its way fairly slowly into Norway compared to Denmark one positive result of this was that many catholic bishops, who had been imprisoned for their faith, later becoming Lutheran. In 1638, it was decided that catholic inhabitants who had still not renounced their faith should have their possessions confiscated.

In 1814, the Constitution voted the separation of Norway from Denmark and also union with Sweden ; nevertheless the nation still remained Lutheran. During the period when Norway was united to Sweden (until 1905), the life and structure of the Norwegian Church was controlled by the Swedish Lutheran Church, in spite of the fact that its administrative base remained in its new capital, Christiana, which is now known as Oslo.

Until 1845 only the Lutheran Church and its Episcopal government were allowed. In 1813 the University of Oslo was set up, with a faculty of theology alongside the already existing faculties of medicine and philosophy. The revival movements had more influence here than in Denmark and there was a certain amount of religious tolerance : Methodists, Baptists, Adventists and Pentecostal Churches were allowed to be officially established in the country.

In 1981, Parliament voted that the Church of Norway should be the State Church, with the king at its head : he would impose his authority through the State Council, or rather through those within it who were baptized members of the national Church. In this way, a Lutheran Head of State would govern the Church – it would not just be governed as if it were a secular body. Laws concerning the Church were to be dealt with by Parliament, which consisted mostly of Norwegian Church members. The “Royal Ministry of Culture and Church Affairs” would be responsible for administrative duties.

In 2002, a report was published, “the same Church – a next Church structure” ; it suggested practical steps towards loosening the ties between the State and the Church, although the Episcopal synodal structure of the latter would remain intact.

Some famous Norwegian protestants were : the dramatist Ibsen (1828-1905) and the composer Grieg (1848-1907).

Website of the Norwegian Church (Den Norske Kirke)

Sweden

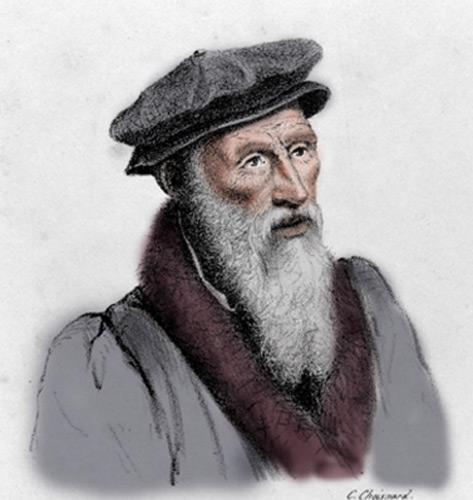

In 1523, Gustave Vasa (1496-1560) forced the Danish to flee from Sweden. When he was elected king, his principal policy as a hero of independence was to break off any remaining ties with the Papacy and to free his country from the economic power of the Church.

He relied on the support of the Petri brothers, who were disciples of Luther, to introduce the Reform movement into Sweden.

In 1527, at the diet of Vasterâs, it was declared that “the word of God should be preached in all purity throughout the kingdom”; in this way the Swedish national Church came into being. When the possessions of the Church (more than 20 per cent of the wealth of the country) were confiscated, Gustave Vasa was able to consolidate his financial position. However, this reform was predominantly an affair of the court and aristocracy – the population was not much involved ; for this reason he held back, considering that a close link with the Reform movement could be dangerous for the stability of his political situation. Indeed, the more radical tendency of the evangelical movement in Germany was not at all reassuring for the king – so much so that he dismissed the reformed members of his council.

Nevertheless, the situation gradually changed : on the one hand his neighbours, Denmark and Norway officially adhered to the Reformation movement, on the other hand, catholic priests gave their support to the peasants’ revolt which was taking place in the south of the country. For this reason, the king felt justified in breaking off relations with the Catholic Church in 1529. The Swedish national Church was officially Lutheran and governed according to a system of synods and consistories, but it still retained many Roman Catholic traditions. Unlike the Danish Church, it was not linked to the State in theory or in practice ; but was semi-independent ; the archbishop of Uppsala continued to be at its head and it only recognized the king’s sovereignty in secular matters.

King John III (1569-1592) had a catholic wife (her brother was the king of Poland) ; under her influence there was a last attempt at reconciliation with the Catholic Church, but it failed. In 1593, his brother duke Charles (later proclaimed king in 1604), called a synod in Uppsala where the decision was made to definitively adhere to the Confession of Augsburg.

In the reign of Gustave II Adolphe (1611-1632), the Swedish Church became more firmly established ; adherence to the confession of Augsburg became compulsory, with no other religion being tolerated. Gustave II Adolphe led his country into the Thirty Years war and became the champion of Lutheranism in opposition to the catholic House of Austria. In addition, he went on to conquer many territories in Russia, Denmark and Poland, thus becoming the absolute master of the Baltic regions. His daughter queen Christina, who succeeded him, followed all the latest developments in learning at that time (and even called Descartes to come and visit the Swedish court). The queen was also interested in theology and abdicated from the crown because she wished to convert to Catholicism.

The XVIIIth century was marked by innumerable wars and sadly for Sweden, a major conflict with Russia. In spite of the military brilliance of Charles II (1697-1718), his kingdom was defeated by Peter the Great and all the former territories were lost. The king had to hand over power to Parliament. The influence of the pietists, who had come from Germany, threatened to divide the country on a religious level ; one of them was called Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688-1718) who created the “New Church”. These tendencies were strongly repressed by the authorities who banned any private religious meeting.

The Constitution of 1809 proclaimed that the king and members of the government had to belong to the Church of Sweden. In I805 king Charles XIII, who had no child of his own, chose the Napoleonic officer Bernadotte to be his successor. He was crowned in 1818, as Charles XIV, had to accept all the demands of his new country and abjure Catholicism. In the XIXth century, democracy made remarkable progress and on the religious level, the Lutheran Revival movements also expanded considerably in this period ; in fact several free Churches were set up (the Methodists, the Baptists, etc.).

At the beginning of the XXth century, Sweden became a leading member of the new ecumenical movement. One of its founders was the archbishop Nathan Söderblom (1866-1931), who won the Nobel Prize in 1930 ; he set up the international commission “Life and Action”, which held its constituent assembly in Stockholm in 1925.

There were many distinguished Lutheran personalities in Sweden, and two stand out particularly : Dag Hammasrskjöld (1905-1961), secretary general of the UN and the diplomat Raoul Wallenberg (1912-1947), who saved the lives of millions of Jews when he was serving in Budapest in 1944.

Today, the Church of Sweden is administered by a general synod, which put forward the names of bishops that are later appointed by the government ; the archbishop of Uppsala is the “primus inter pares”. From 2000 onwards it has no longer been considered an established Church, but rather a “community of faith”. At present, the Church of Sweden has 7.2 million members, that is to say, about 80 per cent of the population. However, there is a great decline in faith and only 2 per cent are considered to be actually practicing Christians. Surprisingly, 90 per cent of its members have a Church burial. The Church of Sweden has many diaconal and missionary activities throughout the world.

Some foreign Lutheran Churches and a reformed Church with 63 000 members also form part of the Swedish protestant community.

Website of the Swedish Church (Svenska kyrkan)

Finland

Lutheranism took hold in Finland, a possession of the Swedish crown, without any particular opposition, in the middle of the XVIth century. The bishop Michel Agricola translated the Bible into Finnish, thus laying down the basis of the language. Finnish Lutheranism retained many characteristics of Catholicism including the worship of the virgin Mary and a belief in purgatory : in this way there was no major rupture for the former followers of Catholicism when the new national Lutheran Church came into being. When Finland was annexed by Russia in 1809, certain popular religious movements displayed a tendency to emotional extremism, which almost led the traditional Church to exclude them from its ranks. From 1869 onwards, the evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland was no longer considered to be a State Church, but rather simply an established Church.

Contrary to most Lutheran Churches, the Church of Finland did not sign the Concord of Leuenberg in 1973. This agreement announced full communion between Lutheran, reformed and united Churches.

84 per cent of the Finnish people (4.4 million) belong to the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church.

The Baltic States

In 1561, when the Teutonic order ceased to be in control of Livonia, Lutheranism became the official religion in Estonia, which had been annexed by Sweden, as well as the independent duchy of Courlande. During the Russian period (starting in 1721), there were many conflicts between the Protestants and orthodox priests : for this reason the pastors of Estonia were of German origin until the end of the XIXth century. Pietism and the Moravian brothers were very influential in the XIXth century.

Estonia (as well as the other two Baltic States) became independent in 1918, after having suffered from the domination of Denmark, Sweden, Germany and Russia for centuries. Religious life was particularly difficult when the three States became part of the Soviet Union between 1940 and 1990 ; they also had to submit to occupation by the Germans during the Second World War.

In 2005 Christians represented 63 per cent of the population : 230 000 protestants who mostly belonged to the Estonian Lutheran Evangelical Church, 220 000 were members of the Orthodox Church and there were very few Catholics.

In Lithuania, which had strong links with Poland, Lutheran parishes mostly came into being through the influence of Prussia. However, due to the Counter Reform movement, the country returned to Catholicism. Today, it remains the major religion (80 per cent) of the country and there are very few protestants (1 per cent).

In Latvia Lutheranism was introduced in 1558 but the western part of the country remained Catholic. The Polish crown took possession of Latvia in 1561 but due to the immigration of a great many German Lutherans, Latvia retained a certain amount of independence, particularly in the religious domain. In 1721, it was taken over by Russia but between the two world wars independence was decreed. The Russians returned to power after the Second World War and encouraged immigration from throughout the USSR ; today among the immigrant part of the population (10 per cent), 30 per cent speak Russian.

67 per cent of the population are Christian : 720 000 are members of the Orthodox Church, 435 000 are Catholic and 280 000 Protestant. The main Protestant Church is the Lutheran Evangelical Church of Latvia.

Bibliography

- Books

- MILLER John, L’Europe protestante aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles, Belin-De Boeck, 1997

- MOURIQUAND Jacques et PIVOT Laurence, L’Europe des protestants de 1520 à nos jours, Jean-Claude Lattès, 1993

Associated notes

-

Protestantism in England in the 16th century (separation from Rome)

Henri VIII’s divorce led to the start of a national Church supported by Parliament. After eleven years of religious turmoil following the king’s death, Anglicanism was established by Elizabeth I... -

Protestantism in Germany

The Lutheran Reformation movement was a crucial event in German history. This theological and religious revolution had a major effect on German politics, language and culture. Today Germany has several... -

Protestantism in Belgium

Although the Low Countries and Belgium (which was in fact part of the latter for several centuries) had shared a common history in the past, the consequences of the events... -

Protestantism in Switzerland

Reformed protestantism is deeply rooted in Switzerland because of Calvin, who lived in Geneva and Zwingli, who lived in Zurich. The Swiss Confederation goes back to the XIIth century ; it... -

Protestantism in Bohemia and Moravia (Czech Republic)

In the XIVth century, Jean Hus introduced the Reform Movement to Bohemia and Moravia (these two countries are now known as Czechoslovakia), where it caught on quickly with the local... -

Protestantism in Italy and Spain

There was fierce opposition to the Reform Movement, so it never really took a permanent hold in these two countries. The Jesuits in Italy, and especially the Spanish Inquisition, were...