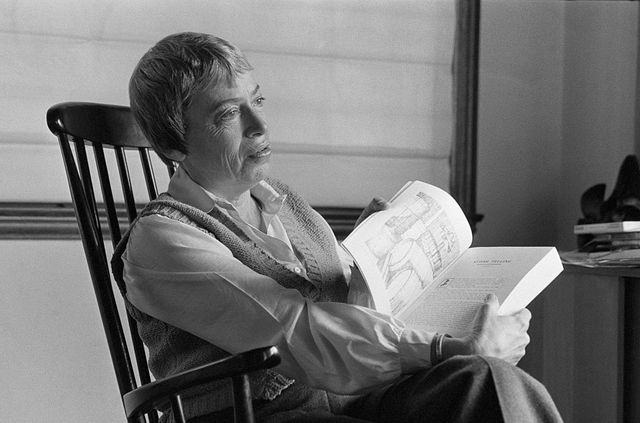

Over the course of a 77-year writing career (she pitched her first story when she was 11), Ursula K. Le Guin became one of the most influential American science fiction and fantasy writers. Unfortunately for the world, that long career ended on Tuesday, when Le Guin died in her Portland, Ore., home at age 88 after several months in poor health.

With 20 novels, dozens of poems, and more than 100 short stories, she created worlds that inspired generations of readers—many who never saw themselves in sci-fi works before—and many future authors. During her Lifetime Achievement ceremony at the National Book Awards in 2014, Neil Gaiman describe Le Guin as inimitable, saying “her words were so clean, so precise, so well-chosen...she raised my consciousness.”

That’s because through her sci-fi and fantasy Le Guin tackled issues that no other writer had ever attempted, themes like feminism, gender identity, and the inevitable corruption of capitalist societies. For example in her acclaimed 1969 novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, a male protagonist is forced to confront his masculinity after exploring a planet of genderless people, and in the award-winning short story "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas," Le Guin questions if the happiness of the many outweighs the immense suffering of one individual.

Le Guin’s stories forced readers to examine how societies—future and present—treat people. It was science fiction that prioritized humanity over technological innovations. It was fiction as a mirror that gazed back into our darker selves.

Despite publishing nonfiction and poetry, she was defined by her science fiction and fantasy writing—and the label irked her. Le Guin didn’t want to follow the rules of any genre, and those rebellions against tradition are what made her books stand out from more the mainstream. In a 2013 interview in the Paris Review, Le Guin explained how her writing diverged from her contemporaries:

“The “hard” science fiction writers dismiss everything except, well, physics, astronomy, and maybe chemistry. Biology, sociology, anthropology—that’s not science to them, that’s soft stuff. They’re not that interested in what human beings do, really. But I am. I draw on the social sciences a great deal.”

Le Guin’s social science focus is why her work feels realistic and accessible, especially those not accustomed to the strange worlds of sci-fi and fantasy. Readers who couldn’t see themselves in predictable stories of daring masculinity or testosterone-fueled space adventures turned to Le Guin, the writer who spun richly detailed fantasy through a feminist lens.

She created her own rules for what a literary science fiction writer could do. “I just didn’t know what to do with my stuff until I stumbled into science fiction and fantasy,” she told the New Yorker in 2016.

Outside her written pages, Le Guin was just as vocal about the same issues that permeated her fiction. She spoke about the effects of capitalism on art and culture and pushed for underrepresented voices in science fiction.

In a blunt letter to an editor who wanted Le Guin to blurb a 1987 anthology of science fiction that didn’t contain any writing by women, she wrote, “I cannot imagine myself blurbing a book, the first of the series, which not only contains no writing by women, but the tone of which is so self-contentedly, exclusively male, like a club, or a locker room. That would not be magnanimity, but foolishness. Gentlemen, I just don’t belong here.”

Because in Le Guin’s world—real and imagined—everyone belonged. Her impact of the genre is undeniable, and contemporary sci-fi is now full of authors who don’t follow the rules. Now contemporary writers blend elements of magic and hard science fiction, and many of them focus on things like gender and climate change.

She taught the world that science fiction and fantasy is not a lesser form of storytelling. It matters. Let’s hope that lesson sticks.