The Quiet Cruelty of When Harry Met Sally

The classic rom-com invented the “high-maintenance” woman. Thirty years later, its reductive diagnosis lives on.

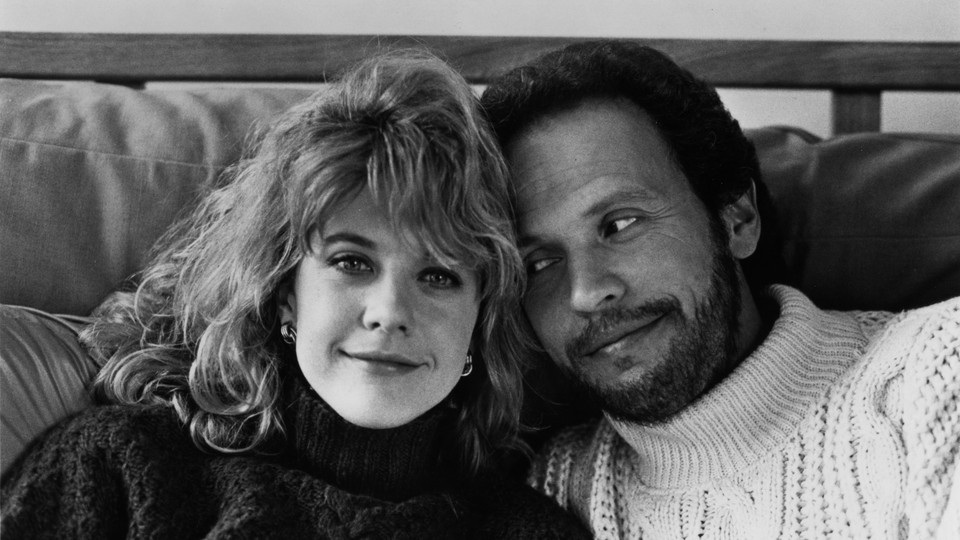

There’s a scene midway through When Harry Met Sally that finds the rom-com’s title couple, one evening, in bed—separate beds, each in their respective apartments, shown on a split screen. The will-they-or-won’t-they best friends, currently in the won’t-they stage of things, are talking on the phone as they watch Casablanca on TV. “Ingrid Bergman,” Harry muses. “Now she’s low-maintenance.”

“Low-maintenance?” Sally asks.

“There are two kinds of women,” Harry explains, anticipating her question: “high-maintenance and low-maintenance.”

“And Ingrid Bergman is low-maintenance?”

“An L-M, definitely,” Harry replies.

“Which one am I?”

Harry has anticipated this question, too—of course Sally would wonder. “You’re the worst kind,” he says, coolly. “You’re high-maintenance, but you think you’re low-maintenance.”

It’s not one of the scenes When Harry Met Sally, which turns 30 years old this month, is best known for—not the wagon-wheel coffee table, not the paprikash at the Met, not the “I’ll have what she’s having.” It’s quieter, and more functional: The scene works mostly to suggest, in a movie about love’s contingencies, a cosmic kind of wrongness. Here are Harry and Sally, who should be together but are not, engaged in the drowsy conversation a couple might have—but over the cold stretch of physical distance.

It is also a scene, though, that made for one of the film’s many lasting cultural contributions. According to the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, it was When Harry Met Sally that popularized the term high-maintenance in American culture. And there it has remained, its use climbing steadily over the past 30 years. An assessment that is also a rebuke, high-maintenance is one of those breezy truisms that is so common, it barely registers as an insult. But the term today does precisely what it did 30 years ago, as backlash brewed against the women’s movement: It serves as an indictment of women who want. It neatly captures the absurdity of a culture that in one breath demands women do everything they can to “maintain” themselves and, in the next, mocks them for making the effort. She wears makeup? High-maintenance. She shops? High-maintenance. She’d prefer the turkey burger? High-maintenance.

As insults go, just as Harry intuited, high-maintenance is extremely effective: Once introduced, it can’t really be argued with. (She is annoyed to be dismissed as high-maintenance? This is, obviously, the clearest evidence of all.) Sally, in the scene that popularized the term, resists the label—or tries to. “I don’t see that,” she protests, when Harry informs her that she is the worst kind. Harry replies with a dramatic rendering of one of her extremely specific restaurant orders: the house salad, but not with the standard dressing, and with the substituted version on the side. The salmon, but with the mustard sauce, and that sauce on the side. “On the side is a very big thing for you,” he concludes.

“Well, I just want it the way I want it,” she says.

“I know. High-maintenance.”

It’s so casual. It’s so bluntly efficient. The man, inventing the categories, and the woman, slotted into them. The man exempt; the woman, implicated. When Harry Met Sally aspired to operate as a kind of allegory—one of the movie’s working titles was the teasingly vague Boy Meets Girl—and there is an aptness to the idea that its hero’s way of reckoning with the world is to reduce it to easy rankings. (On Mallomars: “the greatest cookie of all time.” On Sally: “Empirically, you are attractive.”) Harry’s taxonomic tendencies double as defenses, yes, and as attempts to exert control over life’s chaos. But they are also one of his defining character traits. And, because of that, they infuse the film. One of Harry’s swaggering pronouncements—“No man can be friends with a woman that he finds attractive”—is also the movie’s central premise, and its question is meant to leap off the screen and into the open spaces of audiences’ lives. Can’t he? What if they—? But how about—?

As for Harry’s cold assessment of the world’s “two kinds of women,” the effect might well be the same for the women who watch the film as it was for the one who starred in it. The diagnosis might lead them to question things that don’t really require questioning. Which is also to say that it might lead them to question themselves: Which one am I?

Today there are internet quizzes, as there always will be, to help clarify things. “How High Maintenance Are You Really?” one test offers. “What % High and Low-Maintenance Are You?” invites another. The tests are testaments, in their promises to apply scientific rigor to a question that doesn’t deserve it, to movies’ power as engines of language. (The verb gaslight, for one, which is currently enjoying a tragic renaissance, comes most directly from the 1944 film of the same name.)

But high-maintenance is one of a particular subgroup of pop-cultured insults that are applied, most commonly, to women—a category that whiffs of feminist backlash. There’s MILF, popularized by American Pie; and cougar, popularized by the 2001 book Cougar: A Guide for Older Women Dating Younger Men; and cool girl, introduced by Gone Girl; and gold digger, an insult of long standing recently revived by Kanye West. There’s butterface, derived over time from movies and music. There’s Monet (Cher in Clueless: “From far away it’s okay, but up close it’s a big ol’ mess”). There’s cankle—whose coinage added one more entry to the ever-expanding list of body parts women might feel insecure about—popularized by the allegedly romantic comedy Shallow Hal. (“She’s got no ankles,” Jason Alexander’s character, Mauricio, says. “It’s like the calf merged with the foot—cut out the middleman.”)

The designations are often unfalsifiable, because they live in the eyes of their beholders. And they are often popularized in the context of comedy, which gives them another kind of impunity: Calm down, we’re just telling jokes. As it happens, the 30th anniversary of When Harry Met Sally falls around the time of the 30th anniversary of Seinfeld, the first episode of which aired on NBC in July 1989. The comedies were deeply similar in their contours. Both were propelled not so much by plot as by snappy dialogue; both were, in their ways, shows about nothing that reveled in their reductions of the world and its workings.

Seinfeld did the reveling so giddily that before long it created its own lexicon: Close talkers. Low talkers. Regifters. Mimbos. Man hands. Et cetera. It wasn’t always people whom Jerry & Co. would sort in this manner (see also the double-dip and the big salad and the vault). But Seinfeld walked a fine line. Its classifications, while often deliciously funny, also hinted at something darker, and colder. The show was animated by the idea that people are often more interesting as caricatures than they are as fuller characters and, especially in light of current events, that makes for an uncomfortable proposition.

When Harry Met Sally’s comedy was softer and kinder, but through Harry, it navigated similar tensions. Its solution was to treat its lead’s misanthropy not primarily as a flaw, but rather as a source of charm—and as a vehicle of extreme honesty. (“The only way the movie would work,” the director Rob Reiner has said, “was if we really exposed what men and women really felt and really thought about.”) The film’s writing, courtesy of the brilliant mind of Nora Ephron, insisted that Harry’s assessments of things were not callous, but simply reflections of how things were. When Harry Met Sally is ultimately the story of Harry’s arc: The question it asks, in the end, is not whether women and men can be friends, but whether a guy who hates almost everyone can open himself up to a single someone. That he proves able to evolve suggests an absolution. Sally, at one point, frustrated with Harry’s antics, calls him “a human affront to all women.” She concludes, though, with this: “You make it impossible for me to hate you.”

I’ve found it impossible to hate Harry, too. I’ve loved When Harry Met Sally, in spite of it all. It’s a movie about relationships that is also a movie about seasons—about a world that keeps spinning on its axis, its leaves changing and its people finding ways forward—and there has been, for me, something quietly comforting in that. And so over the years, soothed, delighted, I never bothered to question why it was Harry who met Sally, and not the other way around. I never wondered why it was Harry who changed so drastically over the course of the film, while Sally’s most evident evolution involved her hairstyle. I never paid much attention to all the hints the movie drops that Sally, from almost the beginning of her friendship with Harry, has been waiting for him to decide that, when it comes to her, he wants the sex part to get in the way.

What I did think about, though, every once in a while, was whether the text message I was about to send might make me seem high-maintenance. What I did sometimes wonder, packing a carry-on for a week-long trip, was whether I might be, in spite of myself, “the worst kind.” Movies’ magic can take many forms. Their words can become part of you, as can their flaws. Thirty years after When Harry Met Sally premiered, in this moment that is reassessing what it means for women to desire, it’s hard not to see a little bit of tragedy woven into comedy’s easy comforts. Sally may have gotten a happy ending; she waited so long for it, though. And waiting is not as romantic as her movie believes it to be. Maybe there were times along the way when she almost said something to Harry but didn’t, understanding how easily her preferences could be dismissed as inconvenient. Maybe she questioned herself. Maybe she knew that, despite it all, women who just want it the way they want it are still assumed to be wanting too much.