Students of English literature now tend to take for granted politicised readings of fiction and the ability to talk about Shakespeare in the same breath as Mills and Boon. But things were not always this way, and the discipline owes much of its present freedom and focus to the work of Catherine Belsey, who has died aged 80 following a stroke.

Her book Critical Practice (1980) made her name and transformed the discipline of English literature. In the 1970s academic literary analysis was, in Kate’s words, “looking distinctly dusty” in its belief that works were part of a canon to be transmitted from generation to generation, that criticism was about making value judgments, and that a text was the unique expression of a creative genius.

Kate swept these conservative tendencies aside by revealing the ways in which a canon and value judgments are political reinforcements of privilege, and that texts are products of cultural and linguistic systems.

For instance, in her discussion of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes she examined how the stories subscribe to the wider Victorian and Edwardian cultural belief in the power of “logical deduction and scientific method” to make the unknown known. At the same time, however, the fiction consistently refuses to pay close attention to female sexuality, which remains an enigmatic force on the margins of Holmes’s adventures.

This was not the fault of Conan Doyle himself, Kate concluded. Rather, it was a clue to the contradictions of his moment: everything was meant to be open to scientific analysis, but the patriarchal values of the period left female sexuality beyond the realm of explicit consideration.

Why Shakespeare? (2007) examined the dramatist’s retelling of folklore and fairytales in new ways. Kate first saw most of the plays when the Old Vic put on the complete works over a period of five years while she was a child in London. She in turn retold Shakespeare in radically new ways, putting theory to work in interpretations that drew attention to the linguistic nuances of his texts while teasing out their political relevance in explorations of family roles and values, desire, and subjectivity.

In her later publications Kate returned repeatedly to her belief that literary texts should be studied alongside other forms of culture and that English literature was limiting itself as a discipline if it failed to attend to, among other things, films, paintings, fashion, advertising, and architecture. We can learn much about early modern family values from Shakespeare’s comedies, she stressed, but we can equally learn from 17th-century tombs and privies, for they also exhibit the cultural assumptions of the time.

Delegates at a large academic conference in 1999 were shocked when Kate arrived with a Corn Flakes box measuring more than a metre in height and proceeded to tease out what the packaging suggested to consumers about nature, healthiness and “the good life”.

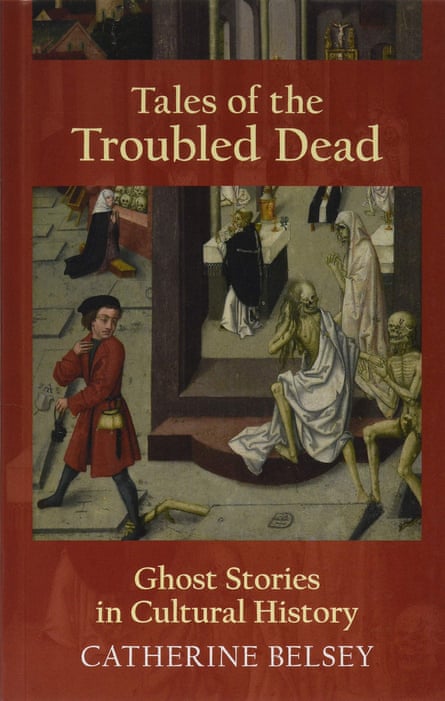

Her last book, Tales of the Troubled Dead (2019), invited readers to take ghost stories seriously – not for their veracity, but for their ability to “unsettle conventional ways of understanding the world” by allowing us to “think beyond the limited categories orthodoxy takes for granted”.

Ghosts occupy a strange realm between life and death, fact and fiction, presence and absence, and their shifting appearances in fiction across the centuries point to what cultures find difficult to name and know.

“If ghost stories maintain their appeal in our sceptical, scientific times, when answers to all imaginable questions are readily available from Google at the stroke of a key,” she concluded, “perhaps that is because tall tales continue to give tenuous substances to hopes and fears that remain outside the reach of science or psychology.”

Born in Salisbury, Wiltshire, Kate was the daughter of Rita (nee Mallett), a primary school teacher, and Jack Prigg, a chemical engineer. From Godolphin and Latymer school in Hammersmith, west London, in 1959 she went to Somerville College, Oxford, to study history, but quickly switched to English language and literature.

After a short spell in publishing and a casual post at London Zoo, in 1966 she went for postgraduate work to the newly opened University of Warwick, which was still in part a muddy building site where new spaces were taking shape. An MA was followed by her PhD thesis on patterns of conflict in the English morality plays, supervised by GK Hunter, and she received her doctorate in 1973.

Following a brief period as a fellow of New Hall, Cambridge, Kate moved to University College, Cardiff (UCC) as a lecturer in English in 1975. There was much resistance to the appointment of a woman to the Cardiff faculty, and Kate learned on arrival that her office was in a different building from the rest of the department and that her salary was lower than that of male colleagues in identical roles. “If I wasn’t already a feminist,” she said many years later, “I was after that.”

Out of her marginalised first few years at Cardiff came Critical Practice, but Kate’s commitment to radical change was not confined to the page. She remained active in local politics until the end of her life and was president and vice-president of the UCC branch of the Association of University Teachers during an era of institutional mismanagement in the 1980s that led to a financial crisis and the merger of UCC and the University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology. That resulted in the formation of what is now Cardiff University, where she was appointed a professor in 1989. Kate’s fearless leadership of the union prevented large-scale redundancies.

Interviewed by Somerville College 50 years on from her arrival there, Kate noted that she was “driven out of full-time academic life in 2003 by the mounting bureaucracy that required me to choose between writing books and compiling reports on the books I had already written, might write, would write if only a space could be made among all the monitoring, planning and applications for funding”.

Although she hated the marketised managerialism of higher education, after she retired completely from Cardiff in 2006 she held visiting posts at Swansea University and the University of Derby, where she encouraged younger generations to fight for a better university and a fairer future. She never lost her radical optimism about the difference that the humanities can make.

In 1965 Kate married the philosopher Andrew Belsey. They eventually separated, and he died in 2019. She is survived by her brother, Simon.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion