Nathalie Peutz first visited Socotra, the largest island in Yemen’s Socotra Archipelago, in 2003. She returned in 2004 and lived for a year and a half in Homhil, a protected area on the eastern tip of the island, where she stayed with the local community and carried out anthropological fieldwork.

"People at first were suspicious of me," says Peutz. "They wondered why an American would want to live in their village." Peutz, an assistant professor of anthropology at New York University Abu Dhabi, has continued to visit Socotra on and off ever since. She has witnessed first-hand Socotra's transformation from a marginalised region, stranded in the Indian Ocean more than 322 kilometres south of Yemen and about 96 kilometres east of the horn of Africa, to a popular tourist destination, after the island was made a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2008 in recognition of its striking flora and fauna (Socotra is often referred to as "the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean"). More recently, Socotra's situation has changed again, the ongoing civil war in Yemen, as well as a pair of devastating cyclones in 2015, destroying the tourism industry.

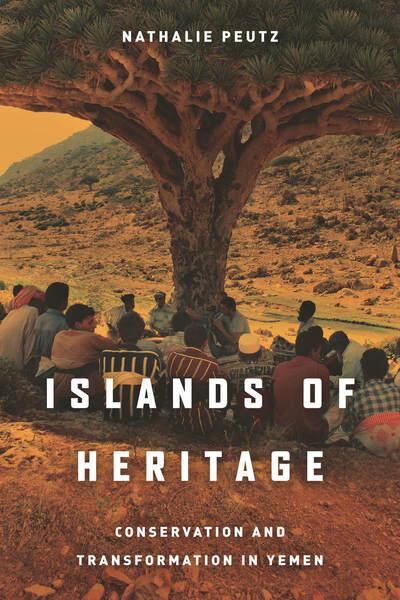

'Islands of Heritage'

Peutz has now written a fascinating book, Islands of Heritage: Conservation and Transformation in Yemen, in which she explores the ways the people of Socotra have responded to the increasing influence of outside forces on their island. Islands of Heritage is less about the animals and plants that make Socotra unique and more about the impact of conservation efforts on the islanders; it is about language and culture and what happens to these when an island experiences rapid and radical change.

Mainland Yemen, of course, has also undergone enormous change since 1990 and the unification of South Yemen and North Yemen. “A political scientist may write about what’s happened in Yemen from the perspective of [the capital] Sanaa,” says Peutz. “But this book tells the story from the perspective of the people [on Socotra], who were never really central to those developments but were still affected by them.”

Too often, she argues, Socotrans are muscled out of the limelight by the very island they inhabit – either because of its biodiversity ("Outsiders linking Socotrans' value to their environment," says Peutz) or because of its strategic significance. This book places the Socotrans front and centre.

The influence of external powers

At the heart of Islands of Heritage is the question of whether or not it is ever beneficial, particularly in terms of conservation and heritage, for external powers to influence and intervene. "Socotra is interesting to me because what is going on there is going on all over the world," says Peutz. "People are worried about cultural loss, language loss and how to retain what it is that makes them distinctive."

Although Peutz points out that interest in Socotra’s natural resources dates back two millennia, modern-day scientific research on the island’s biodiversity began to snowball around the turn of the 21st century. It was during this period that a new term – “the Environment” – was introduced into the lexicon of the islanders, despite, Peutz writes, “Socotrans’ long-standing traditions of resource conservation and regulation.”

It was as if western scientists and conservationists were trying to introduce to Socotrans something that they had relied upon – and maintained – for many hundreds of years. "These are people who have always been completely dependent on their environment in a way that I am not in my daily life," says Peutz.

The conservation effort can also have unintended consequences. Peutz tells me a story, not in the book, about the time she was driving alongside some Socotran men when one of them threw a bottle of Pepsi out of the window. When Peutz asked what he was doing, the man replied: "This is a place of dirt, not 'the Environment' where people come to take pictures."

The parts of Socotra being protected, and promoted to tourists, had seemingly become all that mattered – the rest of the island was now somehow less important.

'Green imperialism'

This pervasive conservation effort in the early 2000s – which Peutz, borrowing the term from British historian Richard Grove, describes as “green imperialism” – was not the only change Socotrans were experiencing, either. Socotran heritage was becoming increasingly important, too.

For the most part, though, this desire to celebrate heritage was generated by the Socotrans and the Socotran diaspora (in 2004, it was estimated that about 5,000 Socotrans lived overseas, the majority of them in the UAE and Oman), rather than by outside forces. In short, the Socotrans felt that, while the world marvelled at the environment, their own history was being forgotten.

As Peutz writes: “This international and state focus on Socotra’s natural heritage generated a concerted interest among Socotrans in their cultural heritage: a heritage they could better define and control – and thus profit from … For at the same time that Socotra was gaining prominence nationally and internationally, it seemed to be losing – according to its emigrants, at least – more and more of its distinctive identity, culture and traditions.”

Distinctively Socotran

What is interesting, though, is that when it comes to heritage, the islanders have managed much more effectively to withstand external pressures. They have curated their own type of heritage, one they recognise as Socotran, rather than one foisted upon them. There are active efforts to maintain the Socotran language; there is a vibrant Socotri poetry community, which for five years supported an annual poetry festival modelled on the UAE's Million's Poet television show; and, in 2008, the Socotra Folk Museum opened on the northern coast of the island.

Reading Peutz’s book, what becomes clear is that, while the preservation of heritage often feels like a nostalgic process, on Socotra it has empowered, rather than hindered, the islanders.

It was, for example, during the period of the Yemeni Revolution in 2011-2012 that Socotrans drew strength from and mobilised their heritage to negotiate for greater political and cultural autonomy. The same Socotrans who had been championing the use of Socotri language through the annual poetry festivals took to the streets and, eventually, the negotiating table to demand political reform, improved connectivity to the mainland, and constitutional protections for their language.

'Heritage is what you make it'

Heritage, which is normally considered conservative, became a rallying call of the Socotran revolution, a vehicle for change. As Peutz explained in a talk last year: "Heritage is what you make it, and if it's your language, your poetry, your ideas, your history, it can really mobilise people."

In the book, Peutz highlights the Socotra Folk Museum as the embodiment of the type of heritage Socotra wants to celebrate – not inward-looking but expansive and inclusive: "The Socotra Folk Museum tells the story not of an island that is 'untouched' or 'lost' … but of a regionally interconnected society that has experienced profound transformations."

Islands of Heritage, then, illustrates that Socotra is not at all the isolated land, unspoilt by the outside world, that we like to believe. This idea fits a western narrative, of course, but in reality, Socotra is very much connected to Africa and the Gulf through historic and contemporary migration.

The UAE's support of Socotra

Peutz tells me that when she started writing the book, she hadn't expected to focus so much on the UAE, which continues to provide humanitarian aid to Socotra, and the Gulf. What is clear is that Socotra both influences and is influenced. "We shouldn't think of the island as insular," says Peutz. Its remoteness, which previously meant it was the poorest region of Yemen, now ensures that it has been largely protected from the war and famine that plagues mainland Yemen.

_______________

Read more:

I saw first-hand the UAE’s efforts to rebuild Socotra

Special report: paradise regained in Socotra

UAE organisation delivers cooking gas to Socotra residents to prevent deforestation

_______________

The path ahead

But what about the future of the island? Will it be able to continue this balancing act between preserving the environment and encouraging tourism? Between maintaining its heritage and negotiating its connections to the Gulf states?

Peutz is cautiously optimistic. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, a year or two from now, people are travelling to Socotra for the weekend,” she says. “If that happens, I think it would be good for all those visitors to see what Socotrans themselves have accomplished. More than anything, I’m really humbled by what Socotrans have done.

“When the war started, all the international NGOs left and it was the Socotran youth who took it upon themselves to clean their island. And when it came to heritage, they realised, ‘We don’t need to wait for experts, we can collect our own stories.’”

'Islands of Heritage: Conservation and Transformation in Yemen' is out now, published by Stanford University Press