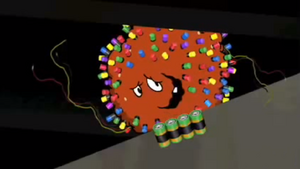

The Boston bomb scare occurred on Wednesday, January 31, 2007, after the Boston Police Department and the Boston Fire Department mistakenly identified battery-powered LED placards resembling the Mooninites from Aqua Teen Hunger Force as improvised explosive devices. Placed throughout Boston, Massachusetts, and the surrounding cities of Cambridge and Somerville, these devices were part of a guerrilla marketing advertising campaign for Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters.

The incident led to controversy and criticism from a number of media sources, including The Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, Fox News, The San Francisco Chronicle, New York Times, CNN and The Boston Herald, some of which ridiculed the city's response to the devices as disproportionate and indicative of a generation gap between city officials and the younger residents of Boston, at whom the ads were targeted. Several sources noted that the hundreds of officers in the Boston police department or city emergency planning office on scene were unable to identify the figure depicted for several hours until a younger staffer at Mayor Thomas Menino's office saw the media coverage and recognized the figures as characters from the TV show. After the devices were removed, the Boston Police Department stated in their defense that the ad devices shared "some characteristics with improvised explosive devices," which they said included an "identifiable power source, a circuit board with exposed wiring, and electrical tape." Investigators were not mollified by the discovery that the devices were not explosive in nature, stating they still intended to determine "if this event was a hoax or something else entirely." Although city prosecutors eventually concluded there was no ill intent involved in the placing of the ads, the city continues to refer to the event as a "bomb hoax" (implying intent) rather than a "bomb scare."

A 2013 publication by WGBH News wrote that the majority of Boston youth thought that arresting two men who placed devices, Peter "Zebbler" Berdovsky and Sean Stevens, was not warranted.

Planning[ ]

In November 2006, Boston area artist Zebbler (aka Peter Berdovsky) met John (aka VJ Aiwaz) in New York City. John worked for a marketing organization named Interference, Inc., and asked Berdovsky if he would be interested in working on a promotional project. Berdovsky agreed and enlisted the help of Sean Stevens for the project. Interference shipped Berdovsky 40 electronic signs. Adrienne Yee of Interference e-mailed him a list of suggested locations and a list of things not to do. According to police, the suggested locations for the devices included "train stations, overpasses, hip/trendy areas and high traffic/high visibility areas." The signs were to be put up discreetly overnight. They were to be paid $300 each for their assistance.

Berdovsky, Stevens, and Dana Seaver put up 20 magnetic lights in the middle of January. They dubbed the activity "Boston Mission 1." While Stevens and Berdovsky put up the lights, Seaver recorded the activity on video and sent a copy to Interference. On the night of January 29, 2007, in what was called "Boston Mission 2," 18 more magnetic lights were put in place. This included one under Interstate 93 at Sullivan Square in Charlestown.

Devices[ ]

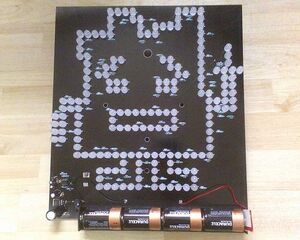

The devices were promotional electronic placards for the forthcoming Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters. Each device, measuring about 1 by 1.5 feet, consisted of a printed circuit board (PCB) with black soldermask, light-emitting diodes, and other electronic components soldered to it, including numerous resistors, a few capacitors, and at least one integrated circuit package. At the bottom was a pack of four Publix brand D-cell batteries, with magnets attached to the back so the devices could be easily mounted on any magnetic surface. The batteries were originally covered in black tape to blend in with the black PCB.

Two variants were manufactured with the LEDs arranged in pixelated likenesses of Ignignokt and Err. Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley said the device "had a very sinister appearance. It had a battery behind it, and wires." Others compared the displays to the Lite-Brite electric toy in appearance.

Scare[ ]

On January 31, 2007, at 8:05 a.m., a passenger spotted one of the devices on a stanchion that supports an elevated section of Interstate 93 (I-93), above Sullivan Station and told a policeman with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) of its presence. At 9 a.m., the Boston Police Department bomb squad received a phone call from the MBTA requesting assistance in identifying the device. Authorities responded with what the Boston Globe described as "[an] army of emergency vehicles" at the scene, including police cruisers, fire trucks, ambulances, and the Boston Police Department bomb squad. Also present were live TV crews, large crowd of onlookers, and helicopters circling overhead. Peter Berdovsky, who had placed the device, went to the scene and video recorded the situation. Berdovsky recognized the device with which the police were dealing, but made no attempt to inform the police at the scene. Berdovsky returned to his apartment and contacted Interference, the company who had hired him to place the lights. He was told by Interference that they would handle informing the police and that he should personally say nothing about the situation.

During the preliminary investigation at the site, police found that the device shared "some characteristics with improvised explosive devices." These characteristics included an identifiable power source, circuit board with exposed wiring, and electrical tape. After the initial assessment, Boston police shut down the northbound side of I-93 and parts of the public transportation system. Just after 10 a.m., the bomb squad used a small explosive filled with water to destroy the device as a precaution. MBTA Transit police Lieutenant Salvatore Venturelli told the media at the scene, "This is a perfect example of our passengers taking part in homeland security." He refused to describe the object in detail because of the ongoing investigation, responding only that "It's not consistent with equipment that would be there normally." Investigators were trying to determine "if it was a hoax or something else entirely," according to Venturelli. By 10:21 a.m. it was determined to be "some sort of hoax device," according to a police timeline of the events.

At 12:54 p.m., Boston police received a call identifying another device located at the intersection of Stuart and Charles Street. At 1:11 p.m. the Massachusetts State Police requested assistance from the bomb squad with devices found under the Longfellow and Boston University bridges.Both bridges were closed as a precaution, and the Coast Guard closed the river to boat traffic.

At 1:26 p.m., friends of Peter Berdovsky received an e-mail from him, which alleged that five hours into the scare, an Interference Inc. executive requested Berdovsky "keep everything on the dl." Travis Vautour, a friend of Berdovsky, stated: "We received an e-mail in the early afternoon from Peter that asked the community that he's a part of to keep any information we had on the down low and that was instructed to him by whoever his boss was." Two hours later, Interference notified their client, Adult Swim. Between 2 and 3 p.m., a police analyst identified the image on the devices as an Aqua Teen Hunger Force character, and police concluded the incident was a publicity stunt. Turner Broadcasting System issued a statement concerning the event at around 4:30 p.m. Portions of the Turner statement read:

"We regret that they were mistakenly thought to pose any danger. The packages in question are magnetic lights that pose no danger. They are part of an outdoor marketing campaign in 10 cities in support of Adult Swim's animated television show Aqua Teen Hunger Force. They have been in place for two to three weeks in Boston, New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, Seattle, Portland, Austin, San Francisco, and Philadelphia. Parent company Turner Broadcasting is in contact with local and federal law enforcement on the exact locations of the billboards. We regret that they were mistakenly thought to pose any danger."[1]

Some devices had been up for two weeks in the cities listed before the Boston incident occurred, although no permits were ever secured for the devices' installation. The marketing company responsible for the campaign, Interference, Inc., made no comment on the situation. Berdovsky and Stevens, the individuals hired by Interference to install the signs, were arrested by Boston police during the evening of January 31, and charged with violating Chapter 266: Section 102A½ of the General Laws of Massachusetts, which states that it is illegal to display a "hoax device" with the motive to cause citizens to feel threatened, unsafe, and concerned. Both were held at the State Police South Boston barracks overnight and were released on $2,500 bail from the Charlestown Division of Boston Municipal Court the following morning.

Reactions[ ]

On February 27, 2007, just a month after the incident, the Boston police bomb squad responded and detonated another object that they believed to be a bomb, which turned out to be a city-owned traffic counter. In the months following the scare, stickers reading, "Don't Panic! This is NOT A BOMB. Do not be afraid. Do not call the police. Stop letting the terrorists win," began to appear on Boston parking meters, ATMs, and other objects in public.

On March 18, 2007, at the annual St. Patrick's Day Breakfast in South Boston, jokes were made about the incident by Massachusetts politicians. Tom Menino said it was a good way to obtain a local aid package for the city (referring to the $1 million in "good faith money for homeland security" that Cartoon Network paid the city of Boston to avoid a lawsuit). Congressman Stephen Lynch claimed that the Mooninites were part of a sleeper cell that also included SpongeBob SquarePants and Scrappy-Doo. State Treasurer Timothy P. Cahill held up a picture of a Mooninite with Mitt Romney's face on it, saying "We had to blur out his real feelings about Massachusetts."

Aftermath[ ]

On February 5th, 2007 state and local agencies came to an agreement with both Turner Broadcasting and Interference, Inc., to pay for costs incurred in the incident. As part of the settlement, which resolves any potential civil or criminal claims against the companies, Turner and Interference agreed to pay $2 million: $1 million to go to the Boston Police Department and $1 million to the Department of Homeland Security. This was in addition to the companies' apologies, which local authorities deemed too little as announced by Dan Conley, district attorney for Suffolk County, Massachusetts, in a speech on NECN, saying the people who are responsible for this "reckless stunt", are liable for the havoc it caused to both the city and the region.

On February 9th, 2007, the week after this occurred, Cartoon Network's general manager and executive vice president, Jim Samples, resigned "in recognition of the gravity of the situation that occurred under my watch", and with the "hope that my decision allows us to put this chapter behind us and get back to our mission of delivering unrivaled original animated entertainment for consumers of all ages". Following Samples's resignation, Stuart Snyder was named his successor. The Boston bomb scare is frequently cited by fans as having directly led to Cartoon Network's first "Dark Age" from 2008 to 2010, when the network relied heavily on imported Canadian cartoons and began emphasizing live-action programming (culminating in the infamous CN Real block) to compete with Nickelodeon and Disney Channel.

In total, ten cities were involved in the marketing campaign, which began two to three weeks before the incident in Boston. The NYPD contacted Interference, Inc., to request a list of 41 locations where the devices were installed. Officers were able to locate and remove only two devices, both located near 33rd Street and West Side Highway at the High Line overpass. The NYPD did not receive any complaints about the devices, according to police spokesman Paul Brown. At 9:30 p.m. on the evening of January 31, the Chicago Police Department received a list of installation locations from Interference, Inc. Police recovered and disposed of 20 of the 35 devices. Police Superintendent Philip Cline admonished those responsible for the campaign, stating, "one of the devices could have easily been mistaken for a bomb and set off enough panic to alarm the entire city." Cline went on to say that, on February 1, he asked Turner Broadcasting to reimburse the city for funds spent on locating and disposing of the devices. Two men were briefly held in connection to the incident.

Fewer than twenty devices were found in Seattle and neither the Seattle Police Department nor the King County Sheriff's Office received 9-1-1 calls regarding them. King County Sheriff's spokesman John Urquhart stated, "To us, they're so obviously not suspicious ... We don't consider them dangerous. In this day and age, whenever anything remotely suspicious shows up, people get concerned —and that's good. However, people don't need to be concerned about this. These are cartoon characters giving the finger."

Interference, Inc., hired two people to distribute twenty devices throughout Philadelphia on January 11.[50] One of these was Ryan, a 24-year-old from Fishtown, who claimed that he was promised $300 for installing the devices, only 18 of which were actually functional. Following the scare in Boston, the Philadelphia Police Department recovered three of the 18 devices. Joe Grace, spokesman for Philadelphia Mayor John F. Street, was quoted as saying, "We think it was a stupid, regrettable, irresponsible stunt by Turner. We do not take kindly to it." A cease-and-desist letter was sent to Turner, threatening fines for violating zoning codes.

No devices were retrieved in Los Angeles and Lieutenant Paul Vernon of the Los Angeles Police Department stated that "no one perceived them as a threat." The many Los Angeles signs were up for over two weeks before the Boston scare without incident. Police Sergeant Brian Schmautz stated that officers in Portland had not been dispatched to remove the devices, and did not plan to unless they were found on municipal property. He added, "At this point, we wouldn't even begin an investigation, because there's no reason to believe a crime has occurred."[ A device was placed in inside 11th Ave. Liquor on Hawthorne Boulevard in Portland, where it remains. San Francisco Police Sergeant Neville Gittens said that Interference, Inc. was removing them, except for one found by art gallery owner Jamie Alexander, who reportedly "thought it was cool" and had it taken down after it ceased to function.

An Aqua Teen Hunger Force episode from season five entitled "Boston" was produced as the series creators' response to the bomb scare, but Adult Swim pulled it to avoid further controversy.[63] The episode has never aired, and has never been formally released to the public legally in any format. However, it was illegally leaked online in January 2015.[64][65] In addition, Ignignokt appears in the Season 5 DVD sleeve, dressed up as Osama Bin Laden. Historical legacy

Author Gregory Bergman wrote in his 2008 book BizzWords that the devices in question were "essentially homemade Lite-Brites".[8] Bergman concluded: "That this occurred in Boston, home to Harvard, MIT, and other famous schools of learning, is embarrassing."[8] Computer security expert Bruce Schneier wrote in his 2009 book Schneier on Security that Boston officials were "ridiculed" for their overreaction to the incident.[9] Schneier wrote, "Almost no one looked beyond the finger pointing and jeering to discuss exactly why the Boston authorities overreacted so badly. They overreacted because the signs were weird."[9] Schneier characterized this as a form of "Cover Your Ass" security.[9]

In his 2009 book Secret Agents, historian and communication professor Jeremy Packer discussed a phenomenon in culture called the "panic discourse" and described the incident as a "spectacular instance of this panic".[6] Packer stated the discovery of the lightboards prompted "a city government and media panic".

The Boston Phoenix published an article in 2012 looking back on the incident and interviewed Zebbler for his thoughts on its place in history. The Boston Phoenix called the incident the "Great Mooninite Panic of 2007". The publication concluded that the city of Boston was impacted due to the fact that it was "oblivious" to the Mooninite character from popular culture. Zebbler thought that history would not be likely to repeat itself with a similar event, and surmised that marketing agencies would instead be more apt to first contact law enforcement to get permission for such an event.

WGBH requested a comment in 2013 from Zebbler to reflect back on the incident, and he stated he thought the overreaction by the government was a greater symptom of the American culture during that time period. Zebbler said he would take part in a subsequent guerilla marketing event if there was a benevolent motivation behind it.

Sources[ ]

- ↑ CNN Statement from Turner Broadcasting Co. by Shirley Powell, January 31, 2007

![[adult swim] wiki](https://static.wikia.nocookie.net/adultswim/images/e/e6/Site-logo.png/revision/latest?cb=20230813010904)