Faraway friction with Palestinians follows some Israelis to World Cup in Qatar

Fans and journalists unable to hide their identities assailed, told to go home by locals and others at soccer tournament, as love of sports unable to overcome geopolitical disputes

DOHA, Qatar — Over the last few years, the once-unthinkable idea of Israelis visiting the Persian Gulf and openly displaying their nationality has become not only possible, but prosaic to the point of banality.

So when Qatar announced that it would allow Israelis to visit the country for the World Cup soccer tournament, some may have assumed they would be welcomed with the same open arms they have received in the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain since the signing of the Abraham Accords.

But instead of kicking it with friendly locals and others from around the Arab world gathering in Doha, some Israelis attending the tourney who have revealed their identity say they have been accosted, badgered or worse, a rude reminder that outside of the autocratic regimes that normalized with Jerusalem, Israel remains deeply unpopular throughout much of the region.

“The atmosphere toward us is hostile,” said Haim, an Israeli fan at the tournament who declined to provide his last name.

FIFA, world soccer’s governing body, pitches the World Cup as a politics-free zone, touting the ability of sports to unify otherwise belligerent nationalities. But despite fans’ shared love of the beautiful game, international affairs have nonetheless dribbled into the tournament, such as Tuesday’s high-stakes matchup between the US and Iran darkly shaded by ongoing tensions between Washington and Tehran. (The US prevailed 1-0 in that game, going through to the last 16 of the tournament and sending Iran home.)

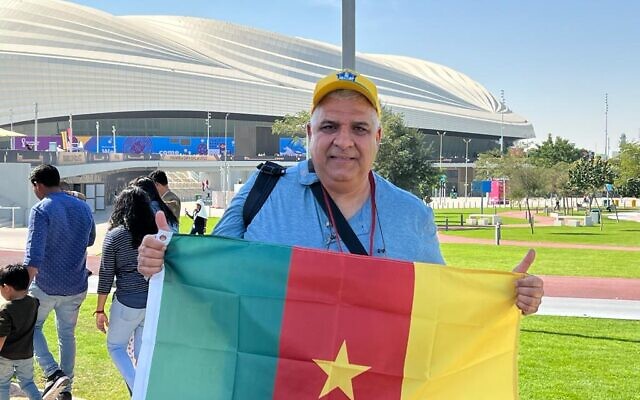

In Doha, national flags are everywhere, carried by fans from the 32 competing countries and countless others from around the globe, with Palestinian flags especially ubiquitous. But Israelis traveling to the tournament were advised by the Foreign Ministry in Jerusalem to not advertise their nationality, leaving their flags at home, along with other symbols that might identify where they are from or, for Israeli Jews, their religion.

Haim, who has been to three previous World Cups, said this year was the first time he had attended without an Israeli flag. A Star of David pendant that normally dangles from his neck was also missing.

“I feel like I’m watching the World Cup in disguise,” he lamented.

Rishon Lezion resident Reuven Eliasi said he had also been harassed by some fans yelling at him: “No Israel, only Palestine.”

But the former career soldier in an elite Israel Defense Forces unit, who served in hostile places like Gaza, Lebanon and the West Bank, said he was not letting the criticism get to him.

“I’m a man who believes in absolute love,” he said. “In the end, the connection is between people, not governments.”

Others have also shrugged off any ill-will toward Israelis, or say they have not experienced it despite not hiding where they are from.

“I tell them I’m from Israel, and they smile and have a lot of questions. Even fans from Iran and Saudi [Arabia],” said Yossi Blank, from the northern Israeli city of Karmiel.

Rotem Raz Rostovsky, who lives and works in Athens, said when he tells people he’s Israeli, some “make a face,” while others are “actually very happy and friendly.”

“I’m not going around with an Israeli flag over here,” he said. “But I speak Hebrew in public. I personally don’t feel any sense of insecurity.”

“At the start, I was concerned because we hadn’t expected there to be so many people here from Arab countries,” he added. “But all-in-all, people are here to watch soccer.”

Among the most prominent incidents of Israelis being abused have been experienced by journalists, who wear lanyards identifying their origin and are unable to disguise their identities.

Dor Hoffman, a soccer commentator for the Kan public broadcaster, said he was kicked out of both a restaurant and a taxi in Doha after his nationality was revealed.

Having filmed the restaurant incident, Hoffman recounted that the owner “asked for my phone, and deleted the videos… I felt threatened. This is part of what happens here, it’s important that it gets told. I’m not seen as an individual here, I’m an Israeli from an enemy state.”

“Everyone needs to be careful here and look after themselves,” Hoffman warned.

Videos of reporters being badgered or yelled at have been shared by both Israelis and Palestinians. Some have been published by Qatari media with the caption: “No to normalization.”

In one video, another reporter for Kan, Moav Vardi, was filmed putting his hands up as he silently absorbed a torrent of abuse from a Qatari wearing a Saudi Arabian soccer jersey.

— Richard Medhurst (@richimedhurst) November 27, 2022

“It is Palestine, there is no Israel. This is Qatar, this is our country, you are not welcome here. There is only Palestine. There is no Israel,” the fan said, in a video that has been viewed more than five million times.

Channel 12 reporter Ohad Hemo shared a video of him arguing back after also being told there is no Israel. “Israel exists, from now until forever Israel exists,” he is seen yelling back at a fan wearing a Palestinian flag.

Here’s another video where Israeli journalist is saying Arabs for some reason are very hostile to him, shows a clip towards the end of Saudi fans repeatedly chanting “Falasteen” while he responds “Israel is a reality and will be until day of judgement” pic.twitter.com/meWFhBK7P7

— لينة (@LinahAlsaafin) November 23, 2022

Channel 13 sports reporter Tal Shorrer said he has been shoved, insulted and accosted by Palestinians and other Arab fans during his live reports from the tournament.

“You are killing babies!” a few Arab fans yelled as they rammed into him during a broadcast.

Shorrer said that while interactions with Qatari officials had been perfectly pleasant, the streets were a different story. Shorrer recalled that a cellphone salesman angrily yelled at a friend to get out of Doha when he noticed their phone settings in Hebrew.

“I was so excited to come in with an Israeli passport, thinking it was going to be something positive,” he said. “It’s sad, it’s unpleasant. People were cursing and threatening us.”

In a lengthy Twitter thread, Yedioth Ahronoth reporters Raz Shechnik and Oz Mualem noted that they had been mocked and criticized, including by Israeli right-wingers, for trying to pass themselves off as Ecuadorian journalists in order to avoid confrontations, including instances where they felt threatened by bystanders during interviews.

“We feel hated, surrounded by hostility, unwelcome,” they wrote. “It’s a great World Cup, true, but we’ll leave here with a very bad feeling.”

An Arab football fan confronts the Israeli broadcaster, who said I am from Ecuador in Qatar. #FIFAWorldCup pic.twitter.com/G8bkUjnY7P

— PALESTINE ONLINE ???????? (@OnlinePalEng) November 28, 2022

Israelis are not the only ones whose tribulations back home have followed them to Qatar. Vlogger Vitya Kravchenko, who fled Russia after President Vladimir Putin announced the “partial mobilization” of over 300,000 Russian citizens in September, said he had faced hostility in Doha from Polish fans.

Kravchenko said that prior to the war, he was a proud Russian. But when asked about his nationality by fellow soccer fans in Doha, “I tell them I’m from Serbia.”

“This war is the biggest catastrophe in my life. When I speak to myself, I say I don’t want to be a Russian. The problem is not about other people, the problem is my own conscience.”

Officials in Qatar, which hosted an Israeli trade office until 2010, have insisted the temporary opening to Israelis is purely to comply with FIFA hosting requirements — not a step to normalizing ties.

The small Gulf nation is largely supportive of the Palestinians, providing hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to Gaza, and Palestinian flags have been on display everywhere around Doha during the tournament.

Eliasi said he understood the backing for the Palestinians, and was unperturbed by the displays of support.

“If people want to raise Palestinian flags, why should I care,” he said. “But if they do it on an Israeli university campus in front of my daughters, then it’s more of a problem.”

Agencies contributed to this report.

Are you relying on The Times of Israel for accurate and timely coverage right now? If so, please join The Times of Israel Community. For as little as $6/month, you will:

- Support our independent journalists who are working around the clock;

- Read ToI with a clear, ads-free experience on our site, apps and emails; and

- Gain access to exclusive content shared only with the ToI Community, including exclusive webinars with our reporters and weekly letters from founding editor David Horovitz.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel