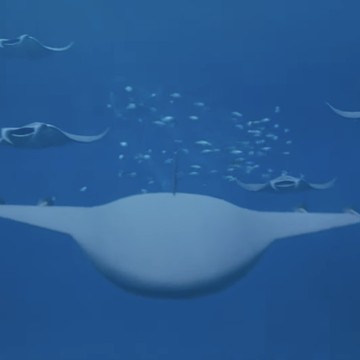

A soldier wears a skullcap that stimulates his brain to make him learn skills faster, or reads his thoughts as a way to control a drone. Another is plugged into a Tron-like “active cyber defense system,” in which she mentally teams up with computer systems “to successfully multitask during complex military missions.”

The Pentagon is already researching these seemingly sci-fi concepts. The basics of brain-machine interfaces are being developed—just watch the videos of patients moving prosthetic limbs with their minds. The Defense Department is examining newly scientific tools, like genetic engineering, brain chemistry, and shrinking robotics, for even more dramatic enhancements.

But the real trick may not be granting superpowers, but rather making sure those effects are temporary.

Augmented Once, Augmented Forever?

The latest line augmentation research at DARPA, the Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology (N3) program, is focused on one key part of augmenting soldiers: making sure the effects can be reversed.

Creating a seamless interface between human and machine invokes images of brain implants and cutting-edge prosthetics. The webpage of DARPA’s program notes that “the most effective, state-of-the-art neural interfaces require surgery to implant electrodes into the brain.” The N3 program, however, falls in line with the current trend in U.S. military research: Figuring out ways temporary, non-invasive ways to enhance soldiers.

The question of reversibility steers a lot of the debate over human augmentation. There are many ways to improve a person, from vaccines to corrective eye surgery. The question becomes when such efforts cross the line into “human enhancement.” Some researchers cite anything above a “baseline human” as augmentation. Laser surgery to correct vision is not enhancement, but a contact lens that enables 4x zooming would be.

Things get thornier as scientists learn more about how to hack the human body and more enhancements become possible. This is most evident in genetic therapy when doctors add DNA containing a functional version of a lost or defective gene back into a cell. Medical researchers are getting good at this: Just this month, medical researchers for the first time cured an inherited disease that blinds its victims. “This restored vision to treated children and adults,” the news release claimed, “and in turn their success enabled the entire field of gene therapy for human disease.”

Just as prosthetics for amputees can lead to exoskeletons, gene-based cures can be adapted to become enhancements. If scientists can discover a way to circumvent a genetic limitation — say, adding cat DNA to human eyes cells to see better in the dark — such therapies can become tools in the enhancement chest. But gene therapy can be reversed by reinserting the original gene. At least, in theory.

Can a Soldier Consent?

The coming issues with human enhancement will ripple across the military and society. The only way to avoid these problems seems to be to make sure the techniques are safe for soldiers and reversible after they are discharged.

Last year, three Canadian defense researchers published a paper that explored the intersection of human enhancement and ethics. They found that the permanence of the enhancement could have impacts on troops in the field (“will unequal distribution of the technology between soldiers cause tension and lead to dysfunction?”) as well as a return to civilian life (“a permanent technology give a veteran an unfair advantage or disadvantage at finding employment?”)

They also note that “many soldier resilience human enhancement technologies raised health and safety questions.” These problems would ease when an enhancement is temporary: A soldier can train to use an exoskeleton and a temporary chemical boost wouldn’t carry into civilian life.

Or would they? A soldier could follow an order to take an enhancement that is considered temporary but in reality has unexpected problems. The Canadian researchers wrote:

“Are there unknown side effects or long term effects that could lead to unanticipated health problems during deployment or after discharge? Moreover, is it ethical to force a soldier to use the technology in question, or should he/she be allowed to consent to its use? Can consent be fully free from coercion in the military?”

The Augmentation Arms Race Is Coming

The Pentagon’s desire for reversible human augmentations over potentially irreversible ones will favor some technologies winning out over others. Exoskeletons over implants, for example. But that doesn’t mean strange-sounding body hacks won’t find their place at the Pentagon.

For example, the military is obsessed with new ways to improve training, and whether soldiers’ brains can be stimulated to learn skills more quickly. A 2018 report from this year’s Mad Scientist conference, a future tech conference run by the U.S. Army, states that “there are studies being conducted that explore the possibility of directly emulating those expert brain states with non-invasive EEG caps that could improve performance almost immediately.” In other words, the term “thinking cap” is about to become more literal.

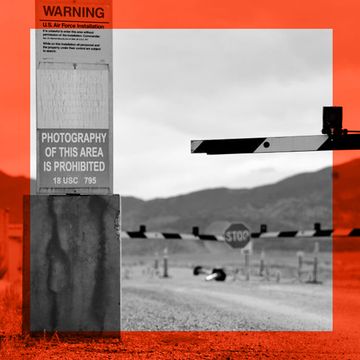

There’s common worry in the defense world that casts a shadow over human enhancement: Will America’s ethics be its downfall, dooming the U.S. to second place in the super-soldier arms race?

After all, totalitarian regimes do not have many ethical limits or transparent media to report on experiments. Gene editing equipment has drown drastically cheaper and easier to use in recent years, putting those tools within reach of well-funded non-government actors such as terrorist groups and drug cartels.

As one U.S. Navy report in 2015 noted: “Major ethical concerns about the voluntary and reversible nature of such augmentations mean that it is more likely these enhancements will first gain traction in state and non-state forces that do not place as much weight on ethical concerns as our own.”

Every medical advance is now eyed for augmentation potential, and not just in the United States. Rogue regimes, terrorist camps, and drug cartels don’t read papers that have phrases “potential ethical issues,” “ policy modifications,” or “ethical assessments.”

In the future, U.S. forces may find themselves on the lagging side of the human augmentation. And they may be happy for it.

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.