Abstract

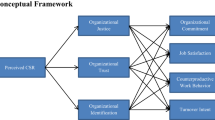

Drawing on the job demands-resources model and positive organizational scholarship, this study examines proactive personality as an antecedent of frontline employees’ proactive customer-service performance (PCSP). It also investigates the potential mediating role of positive psychological states on the relation between proactive personality and PCSP and the potential moderating role of the service-failure recovery climate (SFRC) on the relation between proactive personality and positive psychological states. To test our hypotheses, we used a moderated parallel mediation model and data obtained from 62 branch managers and 358 frontline branch employees of three well-known appliance households and 3C (computers, communications, and consumer electronics) chain stores in Taiwan. The results of multiple-regression and SPSS PROCESS macro analyses indicate that proactive personality was positively related to manager-rated PCSP via employees’ work engagement and perceptions that their work was meaningful. Further, the positive relationship between proactive personality and PCSP through both work engagement and meaningful work perceptions was moderated by SFRC. These findings shed light on the effect of frontline employees’ proactive personality as a personal resource driving their PCSP; the roles of positive psychological states as mediators that help explain the potential intermediary mechanisms; and a boundary condition of SFRC that may weaken the positive relationship between employees’ proactive personality and psychological states. The implications, limitations, and future research directions are included.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the service industries prioritize high-quality customer experience, companies must also develop and leverage enabling factors in their internal and external environments to gain competitive advantages. Employees on the ‘front line’ span the boundary between their organization and its customers, and their work behaviors therefore have a direct impact on how the latter evaluate the former’s service performance and quality. From an interactionist viewpoint, employees’ work behaviors are a function of both their predispositions (e.g., personality types) and work contexts (e.g., organizational climate and leadership style) (e.g., Tett and Burnett, 2003). Proactive employees are characterized by their active responses to challenges and their tendency to influence their environments rather than being constrained by them (e.g., Bateman and Crant, 1993; Buss, 1987). In other words, they create opportunities and, as such, are highly valued by organizations (Fuller and Marler, 2009). Empirically, wished-for performance outcomes at the person-, group-, and whole-company levels have been found to relate to proactive personality (Chong et al., 2021; Haynie et al., 2017) and with job satisfaction (Wang and Lei, 2021) and positive work behaviors (Kim, 2019; McCormick et al., 2019). Using meta-analytic regression analysis with the Big Five personality traits controlled for, Spitzmuller et al. (2015) examined proactive personality’s influence on behavior/performance outcomes and found that it was unique in the cases of overall job performance and organizational citizenship.

Although the effects of proactive personality on individual and organizational outcomes have been fruitfully explored, more research on certain key aspects of it remains to be done. For instance, scant empirical work on the role of this personality type in service occupations has been done. This is fairly surprising, given that proactive customer-service performance (PCSP)—defined as self-starting, persistent service behavior with long-term goals—is seen as an essential component of performance in the service sector (Rank et al., 2007). Front-line employees who deliver customer-service proactively can anticipate and meet work requirements while exceeding customers’ expectations and thus tend to ensure their customers are satisfied. Here, the proactive personality’s nomological network is extended via a reconceptualization of PCSP as one of its outcomes.

Second, the existing literature appears to reflect scholars’ incomplete understandings of both how and when employees’ exhibitions of their proactive personalities achieve desirable outcomes—or, indeed, undesirable ones. This has prompted calls for further empirical work (Sun et al., 2021). Accordingly, from the perspective of positive psychology, our study explores proactive personality’s association with PCSP by considering the parallel mediating effects of an affective, motivational variable, work engagement, and an emotional-experience motivational variable, perceived meaningful work. As well as helping to fill the above-mentioned research lacunae, its research model extends the proactive-personality and positive-psychology literature by conceptualizing perceived meaningful work and work engagement as potential mediators that transfer proactive personality to key work outcomes: in this case, PCSP.

Third, given the potential parallel mediating effects of work engagement and perceived meaningful work, and the ultimate goal of contributing to the improvement of management practices, we construct a research framework based on Bakker and Demerouti’s (2007) model of job demands-resources, hereafter “JD-R”, and use it to identify specific work contexts in which managers can help employees who lack initiative obtain compensating resources, and thereafter demonstrate higher levels of work engagement and perceptions of the meaningfulness of their work. In this effort, exploration of boundary conditions is critically important insofar as it may provide clues about structures or pathways that can offset the lack of proactive personality in the quest for positive management outcomes. Therefore, this study examines whether a particular work context—the service-failure recovery climate (SFRC)—may be able to compensate for poor customer-service performance caused by employees’ lack of proactive personality. As such, the current study can be expected to clarify the relationship PCSP/proactive personality relationship.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Front-line employees’ proactive personality and proactive customer-service performance

As briefly noted above, employees with proactive personalities respond to environmental stress and challenges by attempting to shape their environment in a beneficial direction rather than being unduly influenced by external circumstances (Major et al., 2012). Therefore, as compared with other employees, those with proactive personalities are more likely to recognize opportunities, take active measures to improve their performance, and persevere until their goals are met (Wang et al., 2017).

The PCSP construct, meanwhile, refers to front-line service employees, on their own initiative, improving processes, anticipating future problems and their solutions, and working persistently across all phases of service (Grant and Ashford, 2008; Rank et al., 2007). Behaviors such as these can be distinguished from the mere completion of tasks because the former involves transcending one’s service script, standard operating procedures (Raub and Liao, 2012), and/or job descriptions (Rank et al., 2007). PCSP also differs from customer-oriented prosocial and organizational citizenship behavior in that it involves purposive initiative, forward-thinking, and the adoption of preventive measures (Raub and Liao, 2012).

Previous research has also suggested that proactive individuals believe in their own ability to shape their environments (Bandura, 1977). More specifically, in a workplace culture that encourages people to exceed their formal role requirements, those with proactive personalities are likely to do so. Proactive employees also exhibit high PCSP: i.e., the quality of their work does not slip even when they are dealing with complaints, unexpected requests, and other surprises (Jauhari et al., 2017). In short, PCSP describes employees’ positive behavior in the workplace that goes beyond following supervisory directions and fulfilling job functions and that enables them to determine optimal ways to please customers through high-quality service (Li et al., 2016).

Workers who maximize their usage of workplace resources, and develop their own resources, tend to show PCSP (Raub and Liao, 2012). It has also been argued that a proactive personality is one such personal resource (Zhu et al., 2017; see also Sumaneeva et al., 2021). Therefore, we propose that:

H1. Front-line service employees’ PCSR will be positively associated with their proactive personalities.

Work engagement as a mediator

The connectedness of individuals to their job roles can be termed work engagement (Kahn, 1990). Schaufeli et al. (2002) further defined it as a motivational construct marked by absorption, vigor, and dedication. Schaufeli and Bakker’s (2004) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) defines vigor in terms of energy, willingness, and perseverance; dedication around challenge, pride, and enthusiasm; and absorption, as preoccupation with work, in a positive sense (see also Bakker et al., 2008).

JD-R holds that job resources boost work engagement. These may be external factors such as tech support or streamlined workflow; personal qualities or knowledge; or other miscellaneous factors like the available time. However, they can be broadly divided into two types: job resources (e.g., feedback; social support) and personal ones (e.g., optimism and self-efficiency). Considered a personal resource, a proactive personality makes a person more likely to be highly engaged (Wang et al., 2017) and happy (Cooper-Thomas et al., 2014) in his/her job. And some specific behaviors of proactive employees—e.g., unilaterally expanding their roles and networking—help them shape their working environments to suit them better (Oldham and Fried, 2016). According to Li et al. (2014), proactive personality is linked both to greater control over one’s job control and more support from one’s supervisors. Having such a personality could also drive work engagement by motivating the quest for more or better job resources. Unsurprisingly, then, work engagement is predicted by proactive personality (Mubarak et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2017). The present paper adopts JD-R as its framework for this predictive relationship.

For psychologists, work engagement is a positive psychological state: specifically, one that arises from the quantity and/or quality of workplace resources exceeding workers’ expectations, and that usually therefore leads to better performance (Gorgievski and Hobfoll, 2008). This positive state then enables the expansion of such workers’ thought-action repertoires, i.e., idea-to-execution connections. And people who can create their own resources become more proactive at work (Salanova and Schaufeli, 2008) and thus more likely to provide great service (Wang et al., 2017).

In other words, the demonstrably positive relation between work engagement and PCSP indicates that a proactive personality is a personal resource. Moreover, because an abundance of personal resources helps front-line service workers establish their job resources and rise to a range of work-related challenges, it tends to strengthen those workers’ positive emotions and motivation to be proactive (Rich et al., 2010). Hence:

H2. The relationship between front-line service employees’ PCSR and proactive personalities will be mediated by work engagement.

Meaningful work as a mediator

The perception of one’s own work as meaningful revolves around the concept of value (Hackman and Oldham, 1975). For Steger et al. (2012), meaningful-work perceptions can be broken down into meaning made through work (i.e., work that helps employees to make sense of the world around them), greater-good motivation (i.e., having a job that is useful to society), and positive meaning (i.e., having a career that people considers meaningful). These perceptions have long been explored by organizational behavior researchers, and their importance in the workplace has been widely recognized (Bailey et al., 2019; Lepisto and Pratt, 2017). For example, the unique features of meaningful work and its implications for employees’ perceptions and emotions about their work and organizations are demonstrated by the concepts of workplace spirituality (Petchsawang and Duchon, 2009), which refers to employees’ emotional attachment to their organization or profession, and work activity (Hackman and Oldham, 1976). Moreover, workers who derive a sense of meaning from their jobs have an enhanced sense of well-being outside the workplace, which has been measured in terms of life satisfaction, general health, and a sense of purpose (e.g., Allan et al., 2015; Steger et al., 2012).

Perceptions that work is meaningful also strongly predict workplace performance (Fürstenberg et al., 2021). They are also closely associated with various desirable and undesirable outcomes, including but not limited to job satisfaction, citizenship behaviors, engagement, negative affect, and withdrawal intention (Allan et al., 2019). In an early exploration of the antecedent variables of meaningful work, Hackman and Oldham (1975) showed that task significance and task identity were among the most important determinants of the perceived meaningfulness of work. Other antecedent variables such as transformational leadership (Aryee et al., 2012), perceived organizational support, and personality traits (Akgunduz et al., 2018) have also received empirical support. However, few, if any, prior studies have simultaneously explored the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions of proactive personality, meaningful work perception, and PCSP in an integrated model. This study fills that gap.

As we have seen, due to their receptivity to challenges and openness to the experience of new work and new processes, people who have proactive personalities seek to rearrange their working lives (Campbell, 2000). Therefore, they tend to put their ‘hearts and souls’ into work that is highly meaningful and—if necessary—take risks to find employment that matches their individual personalities (Bergeron et al., 2014). In short, employees with proactive personalities attach great importance to the meaningfulness of work. It seems reasonable to speculate, based on the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), that perceived meaningfulness will trigger employees’ cognitive-affective processes that transform into desired behavioral outcomes (i.e., PCSP). Ritchie et al. (2016) argued that such perceptions trigger positive emotions but also that they both initiate and facilitate the broadening-and-building process, thereby highlighting to people that their own work is important/valuable. Meaningfulness perceptions stimulate people’s interest in work, prompt them to deliver service proactively, and open their minds to new ways of serving. When people’s mindsets are broadened in this way, according to the broaden-and-build framework (Fredrickson, 2001), they will try to build resources of three kinds: psychological, social, and intellectual. When front-line service employees find their work to be meaningful, they seek additional information or new knowledge to improve their task performance (i.e., intellectual resources); and connect with leaders and peers in various departments of their organization to find synergies that will improve their service processes (i.e., social resources); and/or gain a deep understanding of themselves and their surroundings, seize opportunities to provide services that are helpful to customers, and gain confidence in their service role (i.e., physical resources; Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005). Thus, perceiving that their work is meaningful broadens front-line service employees’ mindsets and builds their resource pools, thereby motivating and enabling them to proactively improve service quality and performance.

To explain how a proactive personality may enhance the positive emotions arising from work meaningfulness and how positive emotions that lead to broadened mindsets allow front-line service employees to explore new service approaches or processes that will better serve their customers, this paper will rely on the concept of personal resources and the broaden-and-build theory. Also, because the typical proactive person is self-disciplined and works hard, s/he is likely to devote attention and energy to work, perceive meaning in it, and give importance or value to it (Bateman and Crant, 1993; Crant, 2000). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that employees with strongly proactive personalities will find their work psychologically meaningful and consequently exhibit higher PCSP. This also implies an indirect relationship between proactive personality and PCSP, mediated by meaningful work perceptions. Taking our first two hypotheses in tandem, we therefore suggest that:

H3. Front-line service employees’ perception that their work is meaningful will mediate the PCSR/proactive-personality relationship.

Performance-focused climate as a moderator

In exploring the moderating effect of SFRC, we will not re-test the above hypotheses regarding the main effects of personal resources and our two selected mediating variables (i.e., engagement and meaningful work). Instead, we will focus on the potential interaction between SFRC and personal resources on the grounds that little, if any, research has been conducted on the boundary conditions of two of them: work engagement and meaningful work relationships.

An organizational climate comprises the shared meanings and values that people acquire in a workplace (Schneider and Reichers, 1983); and employees’ ideas of what is important, rewarding, and desired in that environment are filtered through their feelings about such climates (Schneider et al., 1998). In our research framework, the SFRC moderator variable belongs to a subcategory of organizational climate, i.e., its psychological climate, and reflects managers’ support for employees by providing training and other resources that empower them, as well as recognizing it when they correct service failures and rewarding them accordingly. Defining it in this way is in line with the centrality of functional resources both to work-goal achievement and to individual development/growth (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007).

This study, following Menguc et al. (2017), conceptualizes SFRC as an organizational resource. JD-R research’s prevailing view is that organizational and other resources will jointly lead to more positive outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and engagement). However, we propose that the valence of the effects of personal resources on engagement with one’s work and a sense of meaning in that work may be dependent upon whether the moderating resource complements an existing one vs. compensates for one that is absent (Menguc et al., 2017). If the former, it is likely to have a positive effect, and if the latter, a negative one. Thus, we expect that—to the extent it is a resource—SFRC will moderate the impacts of personal resources on perceived meaningfulness and on engagement either positively or negatively, according to whether its function is compensatory or complementary. As noted earlier, employees with highly proactive personalities have a greater sense of their own responsibility for changing unfavorable situations and, therefore, will try harder to find methods and tools for doing so. Further, employees with such personalities tend to have strong learning orientations and self-efficacy in learning and to demonstrate proactive behaviors, including the active pursuit of self-improvement and the active acquisition of knowledge and skills pertinent to their work. Thus, for employees with highly proactive personalities, SFRC is only a compensatory organizational resource.

We have also been inspired by prior literature on the information-ceiling effect, whereby new data are more useful to information-poor individuals than to their information-rich counterparts (Sama et al., 1994). Specifically, such work has prompted us to examine whether SFRC is a moderator of two positive relationships: i.e., of engagement and meaningfulness, on the one hand, and with proactivity, on the other. Based on the information-ceiling principle, we speculate that when managers view SFRC as an organizational resource provided to employees (e.g., service-skills training), employees with proactive personalities will benefit less from it than those who lack such personalities. This is because when employees with less proactive personalities perceive their organization as having high SFRC, they are reassured that—despite their lack of certain service skills—their managers will give them the training and tools they need (complementary resources) to facilitate effective recovery in the wake of service failures. However, for employees with highly proactive personalities who can already recover from this type of failure due to already having acquired the relevant resources, SFRC-derived training, resources, and technical support are not especially invigorating or practically helpful. In other words, the effect of high SFRC on employees with highly proactive personalities is limited. Therefore:

H4. The positive relations between (a) work engagement and (b) meaningful work, on the one hand, and proactive personality, on the other, will be weaker under a high (vs. low) SFRC.

Testing moderated mediation effects

Moderated mediation is a situation in which the operation of a mediation effect is dependent upon another variable (Edwards and Lambert, 2007). Here, we suggest that the strength of our theorized mediating effects of work engagement and meaningful work on the PCSP/proactive personality relationship will be governed by SFRC. Based on H1 through H4, we suggest that among front-line service employees with less proactive personalities, work engagement and meaningful work perception can be stimulated to exert a motivational effect on PCSP in the organizational context of an SFRC. Thus, the mediating effect of PCSP, which is a situational variable in organizations, will be enhanced through work engagement and meaningful work perception in the case of front-line service employees with less proactive personalities. From this, we can infer that PCSP provides opportunities for employees with less proactive personalities to exercise autonomy. To pursue and achieve the required high levels of customer-service performance, employees with less proactive personality traits can be motivated by high PCSP situations provided and modeled by their organizations to develop stronger meaningfulness perceptions and higher work engagement; and, on that basis, demonstrate more PCSP. Thus:

H5. In the indirect relation of proactive personality to PCSP, mediation by (a) work engagement and (b) meaningful work will have weaker effects when SFRC is high.

Methods

Participants/procedures

We recruited front-line service employees and their branch managers from 62 branches of three popular Taiwanese retail chains. The aim of grouping employees with their own managers was to reduce common-method variance (CMV; Podsakoff et al., 2003). In that grouping, the branch managers responded to questions about the PCSP of their own front-line service employees, while the latter answered questions about work engagement, the perceived meaningfulness of work, SFRC, and their own proactivity. Valid returns were collected from all 62 target branches and included questionnaires completed by all 62 branch managers and by 358 non-managers. At least three, but no more than eight people (including the manager) at any participating branch participated (M = 5.78). The per-branch average number of employees (including the manager) was 10, so our overall response rate was 67.7% (i.e., [358 + 62]/[62 × 10]). The proportion of males to females in the sample was almost exactly 3:2. Most participants (78.5%) had college or university degrees. Non-managerial employees aged 20–29 constituted 36.3% of the sample; those 30–39, 37.9%; those 40–49, 21.1%; and those over 50, 4.7%. Such employees had, on average, spent 6.5 years in their jobs (SD = 4.43). Managers, who were 73.8% male, had an average age of 35 (SD = 5.94) and had had their jobs for an average of 7.3 years (SD = 4.45).

Measures

The constructs were operationalized via questionnaire items adapted from prior literature and, except for control variables, were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Proactive personality. We used a six-item version of the proactive personality scale (Parker, 1998) to gauge the non-managerial employees’ proactive personality levels. A sample item was “I excel at identifying opportunities.” Previous studies have shown that this six-item scale has adequate internal consistency and construct validity across various national contexts, including Spain (Claes et al., 2005) and China (Li et al., 2010). This instrument’s Cronbach’s α was 0.94.

Work engagement. The nine-item version of UWES (Schaufeli et al., 2006; Cronbach’s α, 0.94) was used to measure this construct. Its three dimensions—vigor, dedication, and absorption—were each measured via an equal number of items (n = 3).

Meaningful-work perceptions. Five items, comprising a single dimension (May et al., 2004; Cronbach’s α, 0.90), were utilized to capture the front-line employee’s perceptions of work meaningfulness.

Service failure recovery climate. SFRC was measured via a six-item instrument developed by Menguc et al. (2017; Cronbach’s α, 0.92).

Proactive customer-service performance. We measured PCSP with six items adapted by Jauhari et al. (2017; Cronbach’s α, 0.87) from Rank et al. (2007). For these items only, the manager respondents were asked to answer for their subordinates rather than on their own behalf.

Control variables. Non-managerial employees’ ages, genders, education levels, and job-tenure lengths were included as control variables.

Data analysis

We adopted a two-phased approach to the empirical testing of our moderated parallel mediation model and hypothesized relationships. Phase 1 consisted of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of our instruments’ measurement quality and validity, and Phase 2 of multiple linear ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Hypothesis testing was conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 25.

Results

Analysis of the instruments

We expected CMV risk to be relatively high because self-assessment was the basis of our independent variables. Therefore, we tested for it using Harman’s (1976) single-factor analysis. Varimax principal component analysis indicated that only 19.5% of the total variance was explained by the largest factor: far lower than Hair et al.’s (2010) 50% threshold. Thus, CMV risk was non-significant.

Next, CFA and reliability analysis were conducted for the reasons mentioned above. Convergent validity, as indicated by average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings, surpassed 0.50 for each variable (see Table 1), which is acceptable (Hair et al., 2010). AVE was also above 0.50 in all cases, which is likewise acceptable, and composite reliability is >0.60. And as Table 2 shows, discriminant validity was adequate because the square root of the AVE of each construct exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations (Hair et al., 2010).

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics of our variables and the relevant analytical results are presented in Table 2. Apart from the moderator variable, all inter-variable correlations were significant (p < 0.01) and positive.

Mediation test

We used OLS regression and the PROCESS macro in SPSS 25 (Models 1, 4, and 7), developed by Hayes (2013), to test our mediation and moderated-mediation hypotheses. As Table 3 indicates, PCSP was positively and significantly correlated with proactive personality (b = 0.42, p < 0.01; see M3, step 1), supporting H1.

From Table 3, we can see that proactive personality was positively and significantly correlated to work meaningfulness (b = 0.48, p < 0.01; M1, step 1) and engagement with work (b = 0.44, p < 0.01; M2, step 1). When the control variables. proactive personality was added to the model, meaningful-work perception (β = 0.42, p < 0.01; see M3, step 2) and proactive personality (β = 0.22, p < 0.01) were both found to be significantly correlated with PCSP. In combination with our findings regarding H1, this meant that seeing their work as meaningful partially mediated the relationship of PCSP with the respondents’ proactive personalities. Much as in M3’s step 2, we added work engagement in step 3. The results indicate that both work engagement (β = 0.47, p < 0.01) and proactive personality (β = 0.21, p < 0.01) were significantly correlated with PCSP. Thus, in light of our H1 results, work engagement was a partial mediator of the PCSP/proactive personality relation. A bootstrapping analysis (Preacher et al., 2007) to test such mediation effects showed that both were significant: with proactive personality’s indirect effect on PCSP via work engagement being 0.182 (95% confidence interval (CI): [0.13–0.23], p < 0.01), and its indirect effect on it via meaningful-work perception, 0.178 (95% CI: [0.12–0.34], p < 0.01). Thus, both H2 and H3 were supported (Fig. 1).

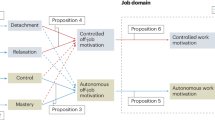

Moderation tests

H4a and H4b respectively posited that SFRC weakens two relationships of proactive personality, i.e., with work engagement and with meaningful-work perceptions (Table 3), with significant coefficients in both step 2 of M1 (β = −0.16, p < 0.01) and step 2 of M2 (β = −0.17, p < 0.01). Thus, H4a and H4b were both supported. To dig deeper into why these interactions occurred, we split SFRC into a “low” variant (1 SD below M) and a “high” one (1 SD above M). Simple-slope plots show a weakening of the positive correlations between proactive personality, on the one hand, and engagement (Fig. 2) and meaningfulness (Fig. 3), on the other, when SFRC was in the “high” category.

Moderated mediation test

To find out whether SFRC moderated the indirect effect of proactive personality on PCSP via the mediation of work engagement and/or meaningful work, we again used the bootstrapping approach. For computing the moderated-mediation index, we used Model 7 of SPSS’s Hayes (2013) PROCESS Macro. If this index differs from 0, it can be concluded that the indirect effect differs across SFRC levels. The results from the model that incorporated work engagement as a mediating variable revealed a significant index of moderated mediation (index = −0.054, 95% bootstrapped CI: [−0.093 to −0.021]): i.e., showed a more pronounced/stronger indirect effect when SFRC levels were low (indirect effect = 0.18, 95% bootstrapped CI: [0.118–0.248]) than when they were high (indirect effect = 0.069, 95% bootstrapped CI: [0.025–0.115]).

Similarly, in the model with meaningful-work perception as a mediator, the results revealed a significant index of moderated mediation (index = −0.036, 95% bootstrapped CI: [−0.066 to −0.013]): i.e., a more pronounced/stronger indirect effect was observed at low SFRC levels (indirect effect = 0.131, 95% bootstrapped CI: [0.067–0.204]) and weaker one at high SFRC levels (indirect effect = 0.058, 95% bootstrapped CI: [0.021–0.104]). Thus, H5a and H5b were both supported.

Discussion

Proactive personality and the psychological processes underlying emotional-motivational and affective-motivational states have been studied very extensively. However, hardly any such research has examined mediating mechanisms. This study confirmed our expectations that front-line service employees’ proactive personality would influence their PCSP via the parallel mediators of work engagement and meaningful-work perception. Additionally, this study’s results confirm our moderated mediation model, which was hypothesized based on the information-ceiling effect. Specifically, SFRC moderates the indirect positive PCSP impact of proactive personality both via meaningful work perception and via work engagement; and this relationship is weaker when SFRC is high than when it is low.

Implications for theory

This study’s findings have four key theoretical implications. First, by expanding JD-R models to include intermediary mechanisms and moderated mediation analysis, we were able to confirm that a positive relation between proactive personality and employee PCSP existed. Employees with proactive personalities actively seek and create opportunities to demonstrate their proactivity and to achieve continuous, meaningful change. They are therefore seen as having a propensity to take actions that influence their work environments (Bateman and Crant, 1993). We thus expect that service workers who have proactive personalities will shape their environments in ways that boost their own performance (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001); and that such shaping will, in turn, inspire them to achieve better PCSP by actively seeking opportunities, strengthening their connections with peers, and maintaining customer relationships.

Second, individual dispositions are conceived of (e.g., under JD-R) as personal resources contributing to engagement with one’s work (Zhu et al., 2017). However, as noted by Inceoglu and Warr (2011), modeling of personality traits’ contributions to job engagement has been rare; and in the decade since they wrote, little has changed, with Wang et al. (2017) and Mubarak et al. (2021) representing two rare exceptions. Regarding mediating mechanisms, the motivational process presented in this study is consistent with that of JD-R theory, which holds that proactive workers tend to be highly engaged and perform well in the workplace, and that work engagement mediates these relationships. These findings align with other recent research results (Lazauskaite-Zabielske et al., 2018), suggesting that certain workers perform well because they can mobilize all their personal resources to cope with intensive work environments. These results are also consistent with Li et al.’s (2017) findings that various mechanisms potentially account for the effects on performance outcomes (including engagement) of employee traits (as personal resources), whether such effects are direct or indirect.

Third, in line with Akgunduz et al.’s (2018) findings, the current study has confirmed that having a proactive personality increases the odds that a person will perceive his/her work as meaningful. We have also shown that workers with such personalities exhibit greater willingness than others to (1) perform work they regard as having value and (2) keep job-hopping until they find a role that is profoundly meaningful to them (Crant, 2000). Our findings also suggest that in service industries, front-line employees’ service performance increases as they accept their work and come to perceive it as meaningful. As well as helping to fill an important gap in the empirical study of work meaningfulness’s performance outcomes (Bailey et al., 2019), this study has revealed that when people complete tasks, they feel are valuable and important, they will fully utilize their skills to pursue success and/or further career-related self-development.

Fourth, the current work upholds the idea that work meaningfulness operates as a mediator: specifically, of the relationship between people’s proactive service performance and their proactive personalities. This rounds out prior conceptualizations of work meaningfulness while also providing evidence—based on our reconceptualization—that a proactive personality enhances service performance. As a whole, supporting Frieder et al. (2018), our findings extend JD-R to include mediating mechanisms whereby service performance is linked to personality via work meaningfulness.

Finally, we considered SFRC not only as a need but also as an organizational resource; and revealed that the proactive personality’s impact on work-engagement/work-meaningfulness relation depends on the proactive personality/SFRC relationship being a compensatory or complementary one. These findings imply that proactivity’s impact on the engagement/meaningfulness relation diminishes in a service-failure recovery environment because SFRC and proactive personality are compensatory; that is, SFRC represents an unfavorable condition. This is again consistent with the information-ceiling literature (Sama et al., 1994). In other words, regardless of the training, resources, or support provided by management, employees with proactive personalities may have already been using these organizational resources proactively in customer-service processes. Conversely, employees with less-proactive personalities appreciate the support provided by management, are more engaged in their work, and have a deeper sense of its meaningfulness. Accordingly, high SFRC can compensate for employees’ less-proactive personalities, and low SFRC can be compensated for by employees’ highly proactive personalities. Here, it should also be noted that our findings are strongly at variance with some previous ones, from research that focused—perhaps too narrowly—on complementarity when looking at how resources impacted the engagement/meaningfulness relation (Fay et al., 2023; Mubarak et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2017). Again, however, we would like to stress the importance of whether resources are complementary or compensatory in particular individuals’ cases.

Practical implications

Our research has shown that the proactive personality of a front-line service employee positively influences his/her PCSP. Therefore, when considering new candidates for front-line service employment, managers should assess their levels of proactivity as an indicator of their future service performance and strive to recruit those with more proactive personalities.

This study has also shown that front-line service employees’ proactive personalities can enhance their work engagement and thus improve their PCSP. Therefore, boosting front-line service employees’ engagement with there work may be critically important to those seeking to inspire them to exceed service-quality expectations. Sonnentag et al. (2010) posited that engagement can be actively developed, but that it is more persistent/stable than various other states: notably, moods. According to Bakker (2015), optimization of their workers’ job demands and job resources can actively stimulate work engagement in organizations. From the present study’s results, it would appear that service providers can enhance the work engagement of their front-line service employees as follows. First, to boost their contentment and facilitate their personal growth, such providers should design their work to be challenging and demand personal agency. Additionally, managers should encourage worker participation in decision-making about service-process improvements and place more stress on opportunities for employees’ growth.

Previous research on the antecedents of meaningful-work perception has focused on identifying how particular job characteristics facilitate it (e.g., Allan, 2017) and tried to avoid viewing bosses as forging meaningfulness-management strategies that their workers then passively receive (Bailey et al., 2017). This study centered on employees’ personality traits, advances that agenda by acknowledging the active role of a proactive personality in creating a sense of meaningfulness. Emphasis on the proactive behaviors associated with having a proactive personality is another approach whereby employees could enhance the perceived meaningfulness of their work. For example, given that task significance has been found to significantly influence meaningful-work perception, benefiting others—i.e., “help behavior” (Lin et al., 2020)—may be key to employees’ experience of work meaningfulness (Allan, 2017). Thus, organizations seeking to enhance the meaningfulness of their employees’ roles could usefully focus such efforts on task significance. More specifically, fostering more opportunities for their workers to positively impact other people, heightening their awareness of such impact (e.g., Allan et al., 2018), or conveying the vision of a desired transformational leadership (Chen et al., 2018), employees’ perception that their work is meaningful can be deepened, and this, in turn, will encourage them to demonstrate positive work behaviors.

Finally, this study’s findings suggest that, under high SFRC, employees with less-proactive personalities may be better at understanding meaningful work’s implications, be more highly engaged in customer-service work, and make greater improvements in their customer-service performance because, in such a climate, their organizations provide them with complementary resources. Therefore, we recommend that organizations implement internal service–remediation mechanisms (e.g., service-skills training, emotion regulation, empowerment, and feedback mechanisms) to enhance employees’ adherence to service values and strengthen their enthusiasm for and confidence in service delivery, as doing so should ultimately enable both the organization and its individual employees to achieve high service performance.

Limitations of this paper and future avenues for research

First, this research relied on cross-sectional data, and thus, its results cannot be the basis of inferences about causality. Accordingly, similar future work should make use of longitudinal designs and/or mixed methods. Doing so would also reduce CMV risk.

Second, proactive personality is the most important determinant of all proactive behaviors, and proactive behaviors are predictive, change-oriented, and self-motivated (Griffin et al., 2007). Thus, follow-up studies with the aim of enhancing performance outcomes could usefully explore the future unpredictability of organizational climate or its moderating effect (e.g., concern climate, performance-focused climate) on how proactive behavior/personality relates to affective and motivational states.

Finally, in focusing on the boundary conditions and mediating mechanisms of the personality/performance relationship, we neglected another research stream: namely, the mechanisms whereby jobs’ social and task characteristics influence performance outcomes. We, therefore, recommend that future studies adopt integrated research frameworks that will allow them to simultaneously explore multiple mechanisms whereby proactive personality and job characteristics directly and/or indirectly affect work engagement and meaningful work perception. In other words, future research needs to clarify the complex black boxes of mediating mechanisms by elucidating both the unique and the shared mechanisms of personality traits and task/job characteristics that affect meaningfulness and engagement.

Data availability

The datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Akgunduz Y, Alkan C, Gök ÖA (2018) Perceived organizational support, employee creativity and proactive personality: The mediating effect of meaning of work. J Hosp Tour Manag 34:105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.01.004

Allan BA (2017) Task significance and meaningful work: a longitudinal study. J Vocat Behav 102:174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.011

Allan BA, Batz-Barbarich C, Sterling HM, Tay L (2019) Outcomes of meaningful work: a meta‐analysis. J Manag Stud 56(3):500–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12406

Allan BA, Duffy RD, Collisson B (2018) Helping others increases meaningful work: evidence from three experiments. J Couns Psychol 65(2):155–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000228

Allan BA, Duffy RD, Douglass R (2015) Meaning in life and work: a developmental perspective. J Posit Psychol 10(4):323–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.950180

Aryee S, Walumbwa FO, Zhou Q, Hartnell CA (2012) Transformational leadership, innovative behavior, and task performance: test of mediation and moderation processes. Hum Perform 25(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2011.631648

Bailey C, Madden A, Alfes K, Shantz A, Soane E (2017) The mismanaged soul: existential labor and the erosion of meaningful work. Hum Resour Manag Rev 27(3):416–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.11.001

Bailey C, Yeoman R, Madden A, Thompson M, Kerridge G (2019) A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: progress and research agenda. Hum Resour Dev Rev 18(1):83–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318804653

Bakker AB (2015) A job demands-resources approach to public service motivation. Publ Adm Rev 75(5):723–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12388

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol 22(3):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Taris TW (2008) Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 22:187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393649

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Gen Learn. https://www.instructionaldesign.org/?s=General+Learning

Bateman TS, Crant JM (1993) The proactive component of organizational behavior: a measure and correlates. J Organ Behav 14(2):103–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140202

Bergeron DM, Schroeder TD, Martinez HA (2014) Proactive personality at work: seeing more to do and doing more. J Bus Psychol 29(1):71–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9298-5

Buss D (1987) Selection, evocation, and manipulation. J Personal Soc Psychol 53(6):1214–1221. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1214

Campbell DJ (2000) The proactive employee: managing workplace initiative. Acad Manag Perspect 14(3):52–66. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2000.4468066

Chen SJ, Wang MJ, Lee SH (2018) Transformational leadership and voice behaviors: the mediating effect of employee perceived meaningful work. Pers Rev 47(3):694–708. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2017-0016

Chong S, Van Dyne L, Kim YJ, Oh JK (2021) Drive and direction: empathy with intended targets moderates the proactive personality-job performance relationship via work engagement. Appl Psychol 70(2):575–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12240

Claes R, Beheydt C, Lemmens B (2005) Unidimensionality of abbreviated proactive personality scales across cultures. Appl Psychol 54(4):476–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00221.x

Cooper-Thomas HD, Paterson N, Stadler M, Saks L (2014) The relative importance of proactive behaviors and outcomes for predicting newcomer learning, well-being, and work engagement. J Vocat Behav 84(3):318–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12240

Crant JM (2000) Proactive behavior in organizations. J Manag 26:435–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00044-1

Edwards JR, Lambert LS (2007) Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods 12(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.12.1.1

Fay D, Strauss K, Schwake C, Urbach T (2023) Creating meaning by taking initiative: proactive work behavior fosters work meaningfulness. Appl Psychol 72(2):506–534. https://iaap-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/apps.12385

Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotion. Am Psychol 56:218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

Fredrickson BL, Branigan C (2005) Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognit Emot 19(3):313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/2F02699930441000238

Frieder RE, Wang G, Oh IS (2018) Linking job-relevant personality traits, transformational leadership, and job performance via perceived meaningfulness at work: a moderated mediation model. J Appl Psychol 103(3):324–333. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/apl0000274

Fuller B, Marler LE (2009) Change driven by nature: a meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J Vocat Behav 75(3):329–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008

Fürstenberg N, Alfes K, Shantz A (2021) Meaningfulness of work and supervisory‐rated job performance: a moderated‐mediation model. Hum Resour Manag 60(6):903–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22041

Gorgievski MJ, Hobfoll SE (2008) Work can burn us out or fire us up: Conservation of resources in burnout and engagement. In JRB Halbesleben (ed.), Handbook of stress and burnout in health care. pp 7–22. Nova Science

Grant AM, Ashford SJ (2008) The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res Organ Behav 28:3–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.002

Griffin MA, Neal A, Parker SK (2007) A new model of work role performance: positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad Manag J 50(2):327–347. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.24634438

Hackman JR, Oldham GR (1975) Development of the job diagnostic survey. J Appl Psychol 60:159–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0076546

Hackman JR, Oldham GR (1976) Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory. Organ Behav Hum Perform 16(2):250–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010) Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall

Harman HH (1976) Modern factor analysis (3rd ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press

Hayes AF (2013) An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050

Haynie JJ, Flynn CB, Mauldin S (2017) Proactive personality, core self-evaluations, and engagement: the role of negative emotions. Manag Decis 55(2):450–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2016-0464

Inceoglu I, Warr P (2011) Personality and job engagement. J Pers Psychol 10(4):177–181. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000045

Jauhari H, Singh S, Kumar M (2017) How does transformational leadership influence proactive customer service behavior of frontline service employees? Examining the mediating roles of psychological empowerment and affective commitment. J Enterp Inf Manag 30(1):30–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-01-2016-0003

Kahn WA (1990) Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad Manag J 33(4):692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Kim SL (2019) The interaction effects of proactive personality and empowering leadership and close monitoring behaviour on creativity. Creat Innov Manag 28(2):230–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12304

Lazauskaite-Zabielske J, Urbanaviciute I, Rekasiute BR (2018) From psychosocial working environment to good performance: the role of work engagement. Baltic J Manag 13(2):236–249. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-10-2017-0317

Lepisto DA, Pratt MG (2017) Meaningful work as realization and justification: toward a dual conceptualization. Organ Psychol Rev 7:99–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386616630039

Li M, Wang Z, Gao G, You X (2017) Proactive personality and job satisfaction: the mediating effects of self-efficacy and work engagement in teachers. Curr Psychol 36(1):48–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9383-1

Li N, Liang J, Crant JM (2010) The role of proactive personality in job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: a relational perspective. J Appl Psychol 95(2):395–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018079

Li WD, Fay D, Frese M, Harms PD, Gao XY (2014) Reciprocal relationship between proactive personality and work characteristics: a latent change score approach. J Appl Psychol 99(5):948–965. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036169

Li Y, Chen M, Lyu Y, Qiu C (2016) Sexual harassment and proactive customer service performance: the roles of job engagement and sensitivity to interpersonal mistreatment. Int J Hosp Manag 54:116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.02.008

Lin W, Koopmann J, Wang M (2020) How does workplace helping behavior step up or slack off? Integrating enrichment-based and depletion-based perspectives. J Manag 46(3):385–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318795275

Major DA, Holland JM, Oborn KL (2012) The influence of proactive personality and coping on commitment to STEM majors. Career Dev Q 60:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2012.00002.x

Wang L, Lei L (2021) Proactive personality and job satisfaction: social support and hope as mediators. Curr Psychol 18:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01379-2

May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM (2004) The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organ Psychol 77(1):11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

McCormick BW, Guay RP, Colbert AE, Stewart GL (2019) Proactive personality and proactive behaviour: perspectives on person-situation interactions. J Occup Organ Psychol 92(1):30–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12234

Menguc B, Auh S, Yeniaras V, Katsikeas CS (2017) The role of climate: implications for service employee engagement and customer service performance. J Acad Mark Sci 45(3):428–451. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11747-017-0526-9

Mubarak N, Khan J, Yasmin R, Osmadi A (2021) The impact of a proactive personality on innovative work behavior: the role of work engagement and transformational leadership. Leadersh Organ Dev J 42(7):989–1003. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2020-0518

Oldham GR, Fried Y (2016) Job design research and theory: past, present and future. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 136:20–35. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.05.002

Parker SK (1998) Enhancing role breadth self-efficacy: the roles of job enrichment and other organizational interventions. J Appl Psychol 83:835–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.6.835

Petchsawang P, Duchon D (2009) Measuring workplace spirituality in an Asian context. Hum Resour Dev Int 12(4):459–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860903135912

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860903135912

Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF (2007) Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar Behav Res 42:185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Rank J, Carsten JM, Unger JM, Spector PE (2007) Proactive customer service performance: relationships with individual, task, and leadership variables. Hum Perform 20(4):363–390. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08959280701522056?journalCode=hhup20

Raub S, Liao H (2012) Doing the right thing without being told: joint effects of initiative climate and general self-efficacy on employee proactive customer service performance. J Appl Psychol 97(3):651–667. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026736

Rich BL, Lepine JA, Crawford ER (2010) Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad Manag J 53(3):617–635. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258130125_Job_engagement_Antecedents_and_effects_on_job_performance

Ritchie TD, Sedikides C, Skowronski JJ (2016) Emotions experienced at event recall and the self: Implications for the regulation of self-esteem, self-continuity and meaningfulness. Memory 24(5):577–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2015.1031678

Salanova M, Schaufeli WB (2008) A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. Int J Hum Resour Manag 19(1):116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701763982

Sama LM, Kopelman RE, Manning RJ (1994) In search of a ceiling effect on work motivation. J Soc Behav Pers 9(2):231–237. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279986463_In_Search_of_a_Ceiling_Effect_on_Work_Motivation_Can_Kaizen_Keep_Performance_Rising

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB (2004) Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi‐sample study. J Organ Behav 25:293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli W, Bakker A, Salanova M (2006) The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ Psychol Meas 66:701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker AB (2002) The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud 3(1):71–92. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schneider B, Reichers AE (1983) On the etiology of climates. Pers Psychol 36(1):19–39. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schneider B, White SS, Paul MC (1998) Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: tests of a causal model. J Appl Psychol 83(2):150–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.150

Sonnentag S, Dormann C, Demerouti E (2010) Not all days are created equal: the concept of state work engagement. In AB Bakker & MP Leiter (ed.), Work engagement: a handbook of essential theory and research. pp 25–38. (Psychology Press). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-06187-003

Spitzmuller M, Sin HP, Howe M, Fatimah S (2015) Investigating the uniqueness and usefulness of proactive personality in organizational research: a meta-analytic review. Hum Perform 28(4):351–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2015.1021041

Steger MF, Dik BJ, Duffy RD (2012) Measuring meaningful work: the work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J Career Assess 20(3):322–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160

Sumaneeva KA, Karadas G, Avci T (2021) Frontline hotel employees’ proactive personality, I-deals, work engagement and their effect on creative performance and proactive customer service performance. J Hum Resour Hosp Tour 20(1):75–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2020.1821429

Sun J, Li WD, Li Y, Liden RC, Li S, Zhang X (2021) Unintended consequences of being proactive? Linking proactive personality to coworker envy, helping, and undermining, and the moderating role of prosocial motivation. J Appl Psychol 106(2):250–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000494

Tett RP, Burnett DD (2003) A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J Appl Psychol 88(3):500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500

Wang Z, Zhang J, Thomas CL, Yu J, Spitzmueller C (2017) Explaining benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of engagement, team proactivity composition and perceived organizational support. J Vocat Behav 101:90–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.04.002

Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE (2001) Crafting a job: revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad Manag Rev 26(2):179–201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378011

Zhu H, Lyu Y, Deng X, Ye Y (2017) Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: a conservation of resources perspective. Int J Hosp Manag 64:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.04.004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Peng made substantial contributions to study conception and design; Peng and Chen contributed to data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation. Author Chen participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Chen gave the final approval for the version to be submitted and any revised versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Research Ethics Committee (Approval No.: 201706ES015) of National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Informed consent

The questionnaire survey in this study only involves minimal risk behaviors research and does not involve personal privacy issues. We obtained informed consent from the participants by enclosing confirmation questions (e.g., voluntary participation; withdrawal at any time; possible uses of their information) for the consent statement in the study questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, JC., Chen, CM. Linking proactive personality to proactive customer-service performance: a moderated parallel mediation model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 700 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02219-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02219-3