In Wolfgang Becker’s classic tragicomedy Good Bye, Lenin!, released two years before Angela Merkel won the 2005 German elections, a woman slips into a coma after a heart attack and misses the fall of the Berlin Wall. When she comes to, the world has changed so completely beyond recognition that her children have to conceal the harsh new reality to prevent another breakdown.

On the 10th anniversary of Merkel’s triumph, it is worth asking: would someone who slept through the past decade be similarly shocked by the spring in history’s step? The change in mood music would certainly be disorienting. In 2005, Germany was still struggling to shake off its reputation as the “sick man of Europe”. Unemployment had risen above 5 million for the first time since the end of the second world war and GDP growth had languished at a measly 1% for four years in a row.

Business analysts at the time proclaimed that German stagnation was dragging down the rest of the eurozone; the Economist worried the ailing German patient had “been infecting the neighbourhood”. Newspaper commentators had long resigned themselves to cultural decline. The end-of-year bestseller lists included titles such as The Art of Falling into Poverty in Style and The Discovery of Laziness, alongside a novel about Weimar classicism and two biographies of Friedrich Schiller: the golden years, it seemed, were a thing of the distant past.

Ten years later, the charge is that the German economy is not too weak but too strong for the rest of Europe. In June, unemployment fell to 2.71 million, the lowest for 24 years. The twin drama of Greece’s bailout and the refugee crisis have thrust the country from the role of spectator to a player on centre stage. Far from dragging its feet, Germany is suddenly seen as a global leader. Whether it is a cold-hearted guard taking us into the debtor’s prison of the common currency, or a compassionate visionary, urging the European family to open its arms to refugees depends on your political sympathies.

Geopolitics has even gatecrashed the same bestseller lists where escapism used to rule supreme. Inside IS, Jürgen Todenhöfer’s interviews with Islamic State fighters, now rubs up against rightwing firebrand Udo Ulfkotte’s Mecca Germany: The Silent Islamisation and Yanis Varoufakis’s Time for Change.

Germany certainly has changed. But to what extent the “Merkel era” is actually defined by her decisions is far from clear. If the economic motor is chugging along nicely, most economists put this down not to Merkel’s policies but the unpopular changes to the labour market that cost her predecessor Gerhard Schröder the chancellorship and put her into power. Unemployment actually started to drop a month before the 2005 election.

If the German economy survived the 2008 crash comparatively unscathed, it was also because it was able to intensify its ties with China just as trade with the rest of the world dropped off. In 2014, China overtook the Netherlands to become the country’s fourth biggest export market. But if Merkel has furthered cooperation between Germany and China, setting up annual de facto joint cabinet meetings in 2011, this too is merely a continuation of Schröder’s recalibration of foreign policy as a tool to further economic interest.

In 10 years, the country has gone from a landmark ruling that allowed tuition fees, to phasing them out again completely, though anyone who tries to credit the chancellor for this doesn’t understand Germany’s federal system. On paper, at least, Merkel’s Christian Democrats remain broadly pro-fees.

On the subject of military intervention, the rise of impossiblynamed defence minister Karl-Theodor Maria Nikolaus Johann Jacob Philipp Franz Joseph Sylvester Freiherr von und zu Guttenberg led to talk of a revival of Prussian militarism and a waning of pacifist instincts. But Guttenberg resigned over a plagiarism scandal in 2011 and Germany opted out of military intervention in Libya the same year. The real gamechanger was the decision to deploy troops to Afghanistan in 2001 – all that happened in the Merkel era was that politicians finally admitted German troops in Kunduz were not just in an “armed conflict” but, in fact, at war.

One thing that has certainly changed is that Germans have become a tad more relaxed about being German. It’s not a nationalist revival as suggested by British tabloid scaremongering, nor philosopher Jürgen Habermas’s notion of a “constitutional patriotism”, a rational attachment to liberal democracy untainted by folkish claptrap. Instead, Germany has fostered a much vaguer notion of “party patriotism”, a phenomenon that first reared its face-painted head during the 2006 World Cup and now sweeps across the country at regular intervals.

Again, the origins may lie before the start of Merkel’s reign: in 2005, a conglomerate of publishers launched a “You are Germany” campaign designed to foster a new “spirit of entrepreneurship”. Unlike Cool Britannia, its UK equivalent, it failed to sweep up the country’s creative class, who launched a counter-campaign called “I can’t relax in Deutschland”, in which bands like Einstürzende Neubauten criticised the “renationalisation of popular culture”.

Still, something seems to have stuck. As many as 38% of the population say they are proud to be German, even if only 16% want to see their country take a leading role in world affairs. Among the young, the rate is even higher: in a 2008 survey, 86% of 14 to 18-year-olds said they were proud to be German, though they weren’t able to put a finger on why – 65% named coming third in the World Cup as a reason. They may just be more honest than their parents.

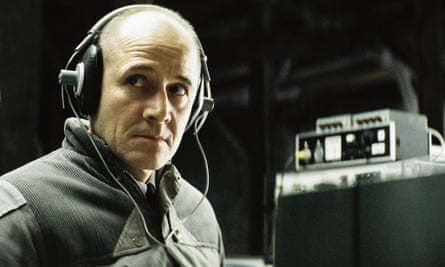

That sleepy vagueness feels like a defining feature of the Merkel era. While Germany’s economic muscle and geopolitical clout have steadily strengthened, its domestic political and cultural pulse has slowed down. At the start of the last decade, a series of German films took box offices and arthouse cinemas across the world by storm: Good Bye, Lenin! in 2003, Fatih Akin’s Head-On and Oliver Hirschbiegel’s Downfall in 2004, and Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others, released in 2006 but filmed in 2004. No German feature film has won at the Oscars or at Cannes since.

Its cultural scene remains vibrant, the craft practised at its theatres and concert halls some of the most skilled in Europe, but the days of provocateurs and mavericks who made a splash outside the national fishbowl – the Herzogs, Fassbinders, Beuys or Schlingensiefs – seem to have passed. Merkel-style consensus politics seems to have trickled down into the arts. Perhaps the most symptomatic product of her decade is a magazine that was launched in the year of her election victory and now sells more than a million copies, more than the revered news weekly Der Spiegel: Landlust, a magazine for those who fantasise about swapping the modern world for country living. The current issue includes special features on autumn flowers and poodles.

Domestic politics too is suffering from “low glucose levels”. As the Spiegel journalist Dirk Kurbjuweit put it in his recent book on Merkel’s Germany: “Our democracy lacks liveliness.” Pollster Manfred Güllner of Cologne’s Forsa Institute says he cannot remember a period in his entire career when the polls have fluctuated as little as they have since the 2013 election. “Germany is enjoying a period of stability and security,” he says. And more than a little bit of complacency.

The Merkel era has seen Germany winning the World Cup of course, with dynamic, sometimes breathtaking, football. But if anything, the football analogy makes for a worrying omen – and not only because the youth sport reforms that paved the way for the triumph in the Maracanã were, again, forced through long before 2005.

Had Germany won the World Cup not in 1990 but in 1994, it would have lifted the trophy exactly every 20 years since 1954. Exactly halfway between these peaks of excitement, there were always troughs of disappointment: non-involvement in 1964, group stage exits in 1984 and 2004.

It suggests a picture of a country that works a little bit like those robot vacuum cleaners: they cruise along gently enough but need to hit a wall before they can reset their system and change direction. What if “Mutti” Merkel is less like the reforming coaching duo Jürgen Klinsmann and Joachim Löw and more like much-loved but risk-adverse Rudi Völler (incidentally nicknamed “Aunty Käthe”, another familial metaphor)? Germany has changed, but maybe it changed in 2005 and it took the country and the rest of the world 10 years to notice. And if the country really follows the logic of its World Cup winners, another trough is just around the corner.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion