“Russian warship, go fuck yourself.” These words, uttered by a Ukrainian serviceman on Snake Island, defined the first day and much of the first phase of Ukraine’s resistance to the Russian invasion. Whether it was the expletives addressed to Russian soldiers on Ukrainian road signs or the memes of farmers towing Russian tanks, a bitter humor has characterized Ukrainian soldier and civilian responses to the war.

Perhaps this is because humor is an underdog’s weapon, and because Ukraine’s president is a former comic actor. However, not every state would turn an obscene meme into a postage stamp, which depicts a soldier flipping off the Moskva warship and sold out in days. As (possible) proof that the jest hit the mark, the Ukrainian postal service reported that it was hit by a cyberattack shortly after. It is clear that the Ukrainian state has seized on the power of humor to define this war.

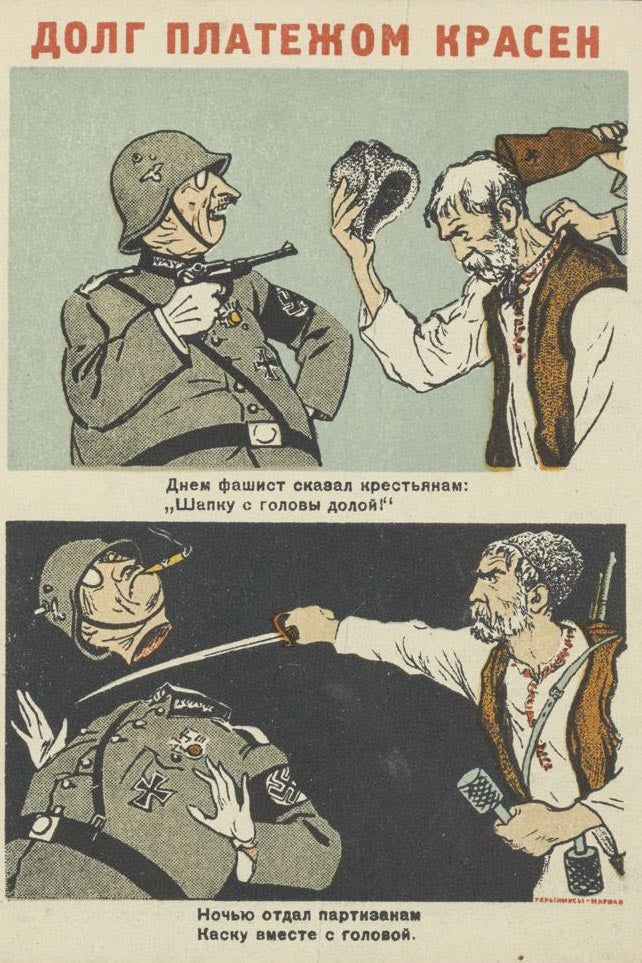

But to fully understand the prominence of humor in Ukraine’s defense, one must turn to history and the legacy of World War II. The Ukrainian state is consciously deploying laughter to define its position on the correct side of a just war, which is a playbook the Soviets used to great effect versus Nazi Germany. In that war, state-sponsored caricatures and humor were used to solidify a moral argument about the USSR’s position and bridge the ideological divide with its U.S. and British allies. Internally, the Soviets recognized the power of laughter to maintain social morale and as a weapon in its own right.

Ironically, in a war where both sides vie for the moral legacy of World War II, Russia seems incapable of laying claim to the war’s humor legacy and all its implications. Russia’s state narratives weave a menacing message about “denazification” and draw somber parallels between today’s soldiers and World War II heroes. Russia’s soldiers may be laughing privately in their trenches, and Russian civilians may be finding ways to do the same, but there is no outward-facing, state-generated humor script to sell a war of aggression, particularly when that war is largely hidden from public view inside the country and diminished to a “special military operation.”

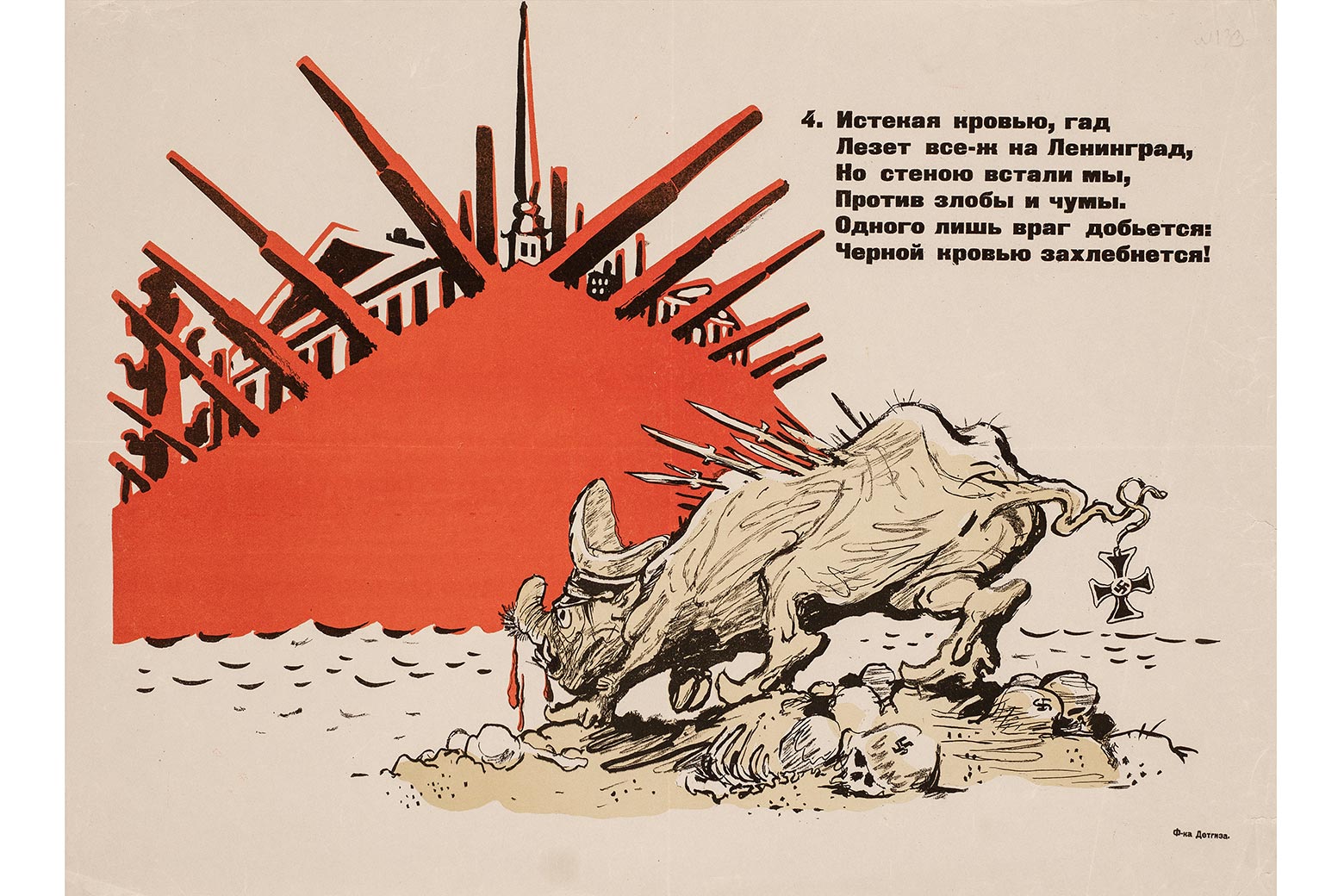

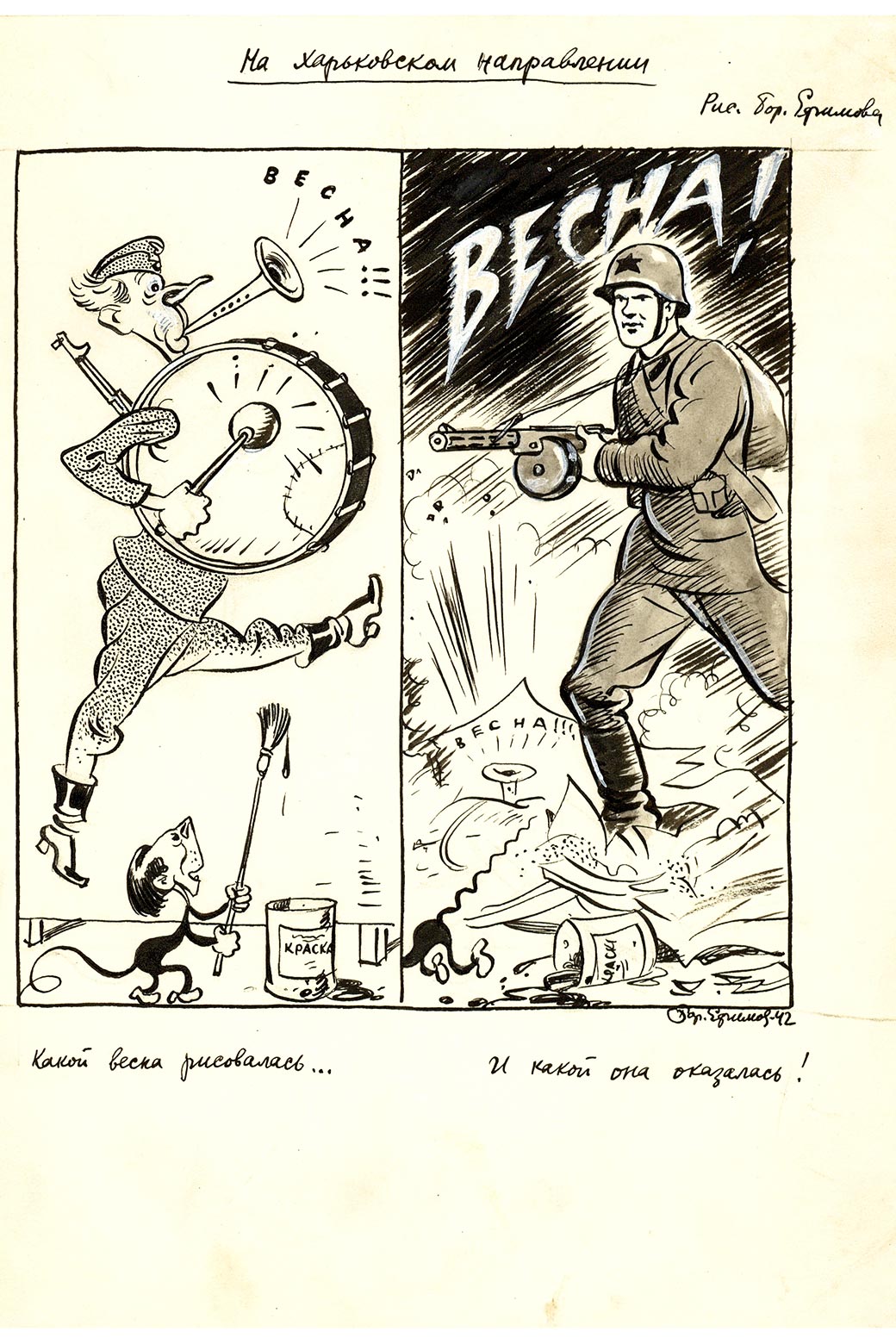

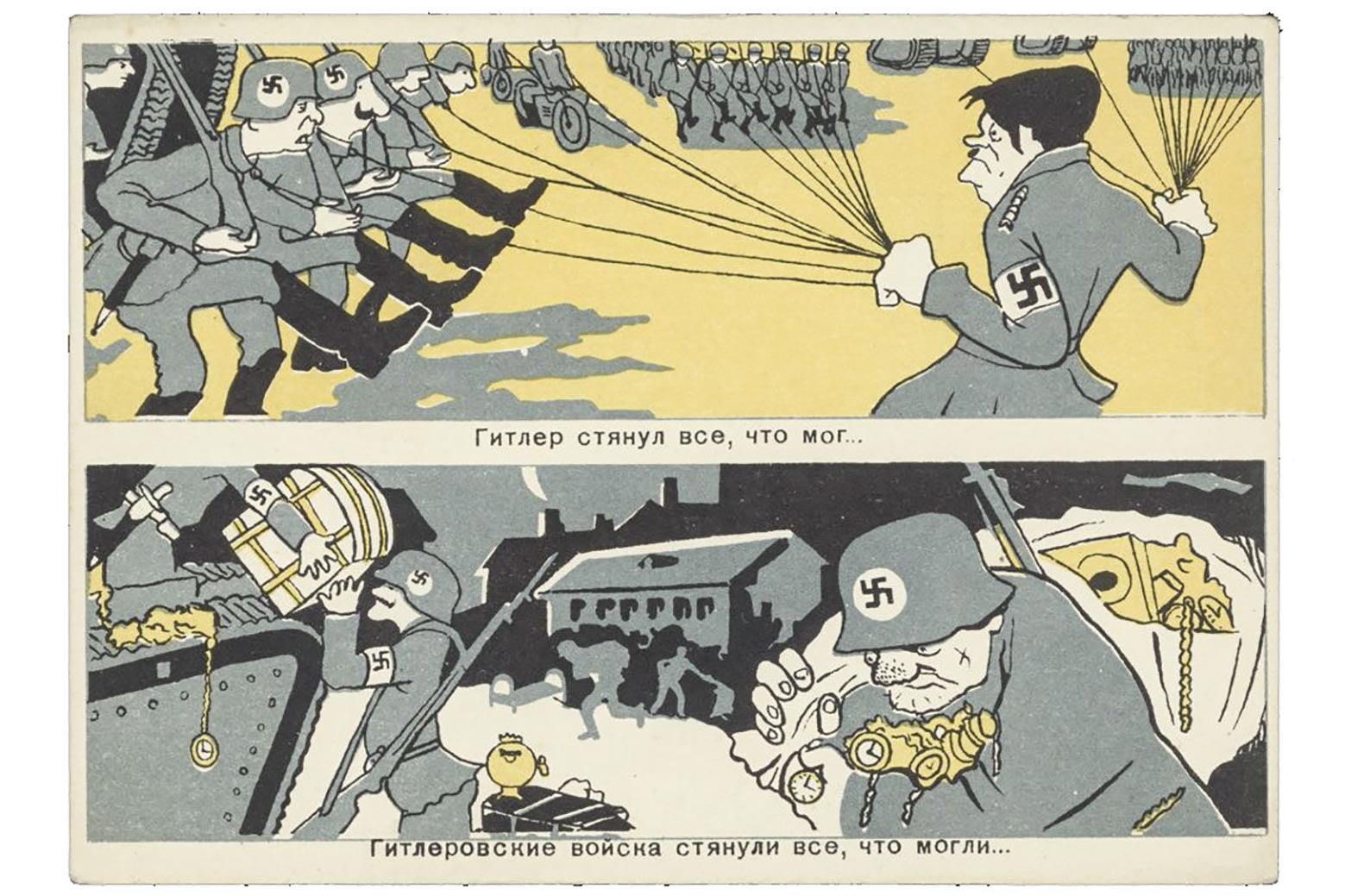

If you ask a Russian today about the humor legacies of the Winter War—Moscow’s disastrous offensive war on Finland (1939–40)—you’ll likely get a blank stare. Ask them the same question about the Great Patriotic War (1941–45) and they’ll recall the iconic caricatures ridiculing Hitler as well as the “fritzes” that adorned daily updated poster displays—called “TASS Windows”— throughout the homefront, or the bitter but urgent calls for violence from Soviet poets. The surviving military veterans would recall a righteous laughter that suffused the front lines, where each army published its humor anthology, soldiers traded humor magazines for tobacco, and tank drivers carefully stenciled their own renditions of Soviet caricature art on their armor.

When the Wehrmacht invaded Soviet territory on June 22, 1941, the centralized Soviet culture industry sprang into action, building off long-standing Soviet notions of collective laughter as a bonding tool for class formation and a way to demarcate friend from enemy. As graphic artist Dmitri Moor said of Soviet humor in 1938: “We don’t have laughter for laughter’s sake, simple belly-laughs … just like we don’t have art for art’s sake. Here, art and laughter are implements of battle.”

Not only was state-sanctioned humor ubiquitous—it was central to the Soviet state’s conception of the war, which was framed as a conflict between those who laughed openly and those who could not. In its first issue after the German invasion, the main Soviet satirical journal, Krokodil, announced: “Murderers do not know how to laugh. Murderers are afraid of laughter. In fascist Germany laughter is banned.” On the Soviet side, the journalist David Zaslavsky claimed in 1943: “Unflinching and stalwart is our certainty in our just cause, our victory. The talented Soviet people performs its selfless work … with happy jokes and laughter.”

If laughter was the barometer of a just war, it was also recruited to perform a variety of tasks for the Soviet war effort. The celebrated poster artist and Kyiv native Boris Efimov noted that caricaturists were like “snipers,” on the lookout for any enemy mistake or misfortune. Their job was to “find his vulnerable, funny points, for if they are found and the enemy is made to look funny … the person who laughs at his enemy will become higher than the enemy, he will overcome his fear.” For Efimov, the connection between laughter and dispersing fear was a “simple physiological sensation”: Laughter gave a positive charge and, hence, relief. And for both state and society, the sense of relief must have been especially palpable now that the weapons of Soviet humor, which for years had been trained against “Trotskyites,” “wreckers,” and other internal enemies, could now be pointed at a common external threat.

But this enemy was burning Soviet towns, murdering civilians, and laying waste to the Soviet army. Because of that, this war humor would be tinged with hate. Ilya Ehrenburg, a novelist and war correspondent, clarified the role of the Soviet writer in such conditions: “It’s often said that we need to teach the people to hate. I don’t think it’s possible, just like you can’t teach love. Hatred is born in our people. They learned it at Istra, at the gallows of Volokolamsk.” (These towns were largely reduced to rubble in the German march toward Moscow. Upon Soviet liberation of these locations in December 1941, Ehrenburg, who was there, described seeing a gallows with eight Soviet civilians hanging.) “Writers have given shape to these feelings and pointed them in one direction”: In other words, writers provided the oxygen to sustain the people’s fire and made sure it blew toward the enemy. “You can teach disdain, and you must teach disdain,” he went on. “Our people still don’t adequately disdain the enemy.”

Made in July 1943, the summer after Stalingrad, Ehrenburg’s statement is chilling, reflecting his belief in the need to move beyond a baseline hate to foment peaks of pointed resentment and sustained vengefulness. The way to do this was to make better satire: to unmask the hypocritical essence of “fritzes” who, despite their pretense toward “culture” and material wealth, were methodically and “pedantically” subjecting Soviet civilians to looting and slaughter. He added: “They’re so repulsive to us that no one could possibly worry about the fate of Germany after the war. Right now Germans just disgust me. And there is nothing wrong with that.”

To kill, to bring relief, and to overcome fear: There was a heavy burden imagined for Soviet war humor, yet the consensus was that humor had risen to the challenge. In 1942 the three-person caricature team Kukryniksy and the artistic collective behind the TASS Windows won Stalin Prizes, the Soviet Union’s highest honor. In July 1943, for the first time in its existence, the Union of Soviet Writers, which was formed in 1934, gathered to discuss satire and humor, and the leading lights of Soviet culture agreed that the war had brought “gigantic growth” to the role and meaning of laughter in Soviet society. One writer enthused about humor’s role in creating a “moral-political unity that our enemies lack.” Another described poster art as the “daily bread of the spirit” for Soviet civilians.

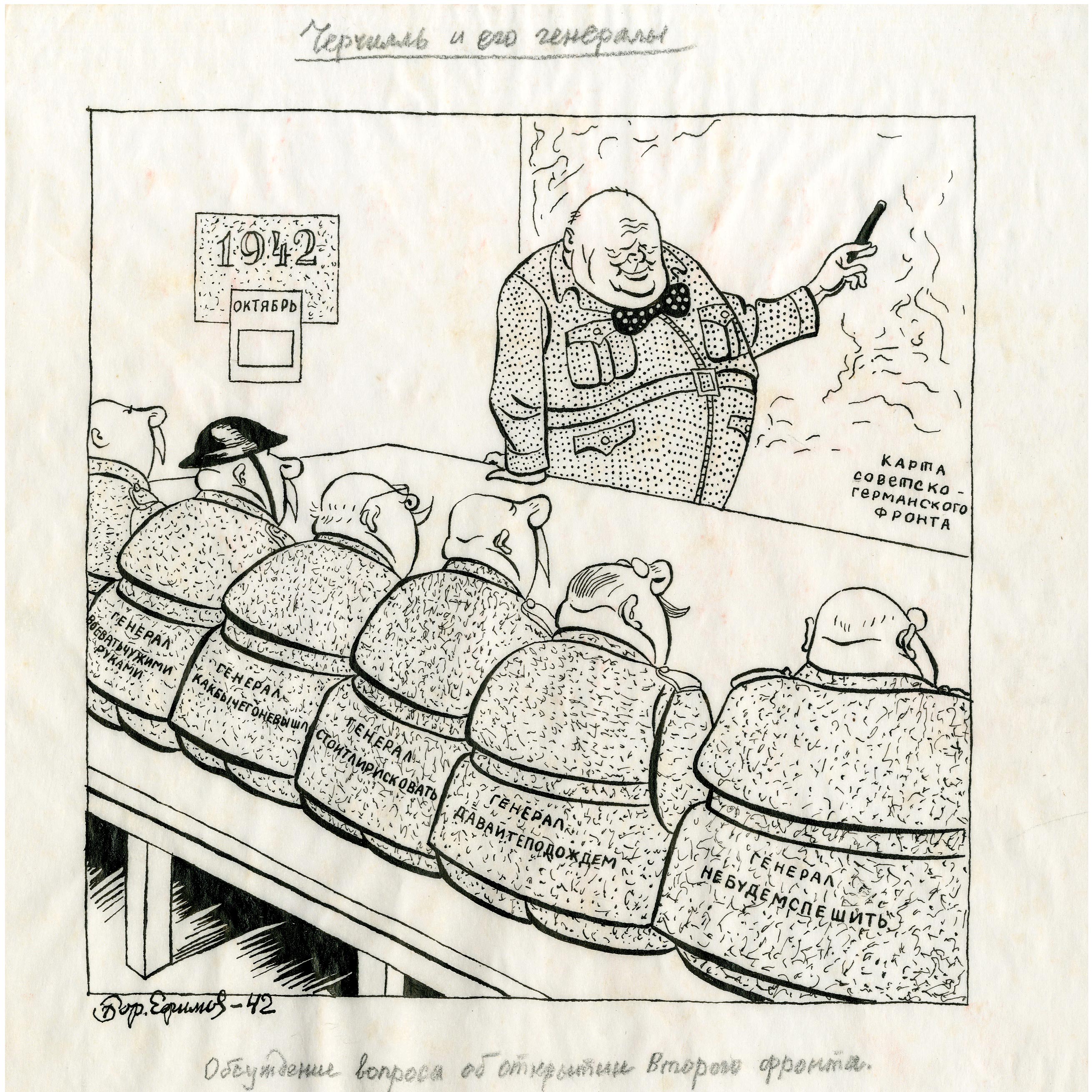

As with the Ukraine-generated memes of today’s war, Western observers kept a keen eye on humor to gauge Soviet spirits, translating cartoons in newspapers and even describing caricature art on the radio in painstaking detail. Aware of this attention, the Soviet state employed laughter and caricature as public diplomacy to build trust with its cautious allies, and then to shame Western publics and statesmen into opening a second military front in Europe. TASS Windows, with their levity and grim bitterness, created a sense of urgency when included in the Soviet war aid exhibitions that traveled across the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, inviting viewers into the emotional life of a people under siege.

Efimov and other artists essentially produced for foreign publics, sending cartoons to friendly artists and requesting their publication in local newspapers. In September 1942, for example, Efimov’s cartoon “The Sword of Damocles” appeared in the Manchester Guardian and the Evening Standard (London), showing a giant British sword looming over the head of Hitler and a disinterested leadership unwilling to drop it. Meanwhile, the description of another cartoon, “A Conference of War Experts,” which featured a ticking clock and characters like “General No Hurry” and “General Let’s Wait,” appeared in newspapers across America. Alongside articles about Stalin calling upon allies of the Soviet Union to “fulfill their obligations fully and on time” and about Churchill evading the topic, cartoons helped build pressure that ultimately was not released until D-Day, June 6, 1944.

And on the front, where it was most needed, humor was doing its job. Soldiers devoured the humor section of front-line newspapers and wrote in suggestions and criticisms for Krokodil. More than just engaged consumers, soldiers were deemed the truest sources of laughter and authors in their own right. The image of the mirthful, decent Soviet soldier was built through classic poems like Aleksandr Tvardovsky’s “Vasily Terkin” and through front-line humor compilations that placed the jokes of soldiers and esteemed Soviet writers side by side. In fact, Soviet writers were encouraged to take inspiration from soldiers’ humor, which was (correctly) imagined as bolder, and uninhibited by editors.

But their just cause wasn’t the only reason why Soviet soldiers were supposedly always laughing. As the writers contended, Russians were innately jovial. Of course, national character could not be connected with blood, for that was the claim of Nazi race science. Instead, Soviet writers looked to history to explain the Russian funny bone. Where did they find this Russian humor? Ukraine.

To open his keynote speech at the writers’ conference, the journalist Zaslavsky, himself born in Kyiv, reached for Nikolai Gogol, a Poltava native from central Ukraine whose novella Taras Bulba (1835) celebrated the Cossacks’ freewheeling spirit (and lethal enmity for Poles and Jews) as well as their use of a so-called caustic word (not a specific word, but a bitter and biting way of speaking) deployed in battlefield taunts. Then he turned to Ilya Repin, born near Kharkiv to a family of Cossack descent, whose painting Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1891) depicted the boisterous laughter of Cossacks in the midst of writing a famously vulgar (and apocryphal) reply to the “Turkish sultan” Mehmed IV’s request for capitulation. He finally turned to Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) as evidence of humor’s ubiquity when war is just but did not use this novel to define the flavor of Russian humor. Rather, for Zaslavsky, it was the Cossacks, the noble savages at the heart of competing Ukrainian and Russian national projects, whose “caustic word” and alleged love of freedom inspired the caricatures of Hitler and the “fritzes” that suffused Soviet wartime culture.

When a Soviet island naval base near Hanko, Finland, was bombarded for several months at the start of World War II and urged to surrender, its defenders penned an obscene response in the Zaporozhian style to the commander of joint Finnish and German forces, “his highness the henchman … the excellent executioner of the Finnish people … the chief whore of the Berlin court … Baron von Mannerheim.” In December 1943, German forces dropped leaflets around Soviet partisans in the Pinsk marshes bordering Belarus and Ukraine, urging “partisan Ivan” to return to his family and farm. The reply to “uber-scoundrel Hitlerishka,” written entirely in rhyming verse, was a relentlessly vulgar mockery of the Nazi war effort and evades easy translation. Its primary author was a journalist from the Ukrainian city of Poliske (which is now a ghost town in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone) who was promoted to Communist Party membership immediately after the war. Filled with scatological disdain, it offers Hitler and his clique a final wish: “Fuck off. Clear out of Russia, we say seriously, while it’s not too late. If you don’t leave in peace, we’ll fill your throats with shit. Goebbels and Ribbentrop, we’ll drive a stake up your asses. To you [Hitler], we’ll beat you with a club and hang you by your dick.”

The letter’s power was twofold: It would have made accepting the Germans’ offer unthinkable to any “Ivan,” and it expressed Ehrenburg’s mantra on disdain in the lexicon of a war of extermination. The imagery evoked brutalization and revenge, which forecast with terrible clarity the conduct of Soviet soldiers on European territory. If there is a uniquely expressive potential in Russian profanity, as many believe, it may be rooted in the need to express linguistically the Soviet experience of World War II.

We often forget that Ukraine has been at war since 2014, honing its laughter on a Russian enemy, disentangling a shared Russian-Ukrainian culture while defining a clear sense of Ukrainian identity. Back in 2017, on his sketch comedy show, Volodymyr Zelensky played the salo-eating bumpkin patriarch in a sketch called “A Ukrainian Family Through the Eyes of Russians.” Suddenly bored, he demands: “Wife, get me a sheet of paper. Let’s write a letter.” “To whom?” his wife asks. “To whom? To whom?! To the Turkish sultan. We morons don’t know how to write a letter to anyone else,” he jokes bitterly. The sketch ends by posing a question asked by many Russians. His neighbor arrives: “Say, you and I are Ukrainians, right? Then why do we always speak together in Russian?” Zelensky’s character retorts, “How else will the Russian viewers understand what morons we are?” Zelensky’s stage performance is composed, but angry. With an eye to the history of Soviet war humor and the power of the “caustic word” to inspire one’s fellows, it becomes clearer that Zelensky was elected president not despite being a comedian, but because he was one.

On Feb. 24, a different invader issued a different order to capitulate. The reply was immediately recognized by Ukrainians and Russian war critics as a retort to the sultan, laconic enough for Twitter. In the next days, a picture of Ukrainian soldiers painstakingly reenacting Repin’s group portrait during the 2014 Russian invasion “blew up the internet,” according to one news portal, marking a definitive repatriation of the painting and much of the Soviet World War II humor legacy back to Ukraine.

In the era of social media, the Ukrainian state can outsource much of the humor content to private citizens; however, it has clearly recognized that laughter is a barometer for a just war as well as an essential tool for preserving morale. Roman Hrybov, the Snake Island defender with the Cossack wit, was awarded military honors. As with Efimov’s caricatures, Ukraine’s humor is broadcast to a foreign audience with an implicit goal of pressuring allies to increase military aid. The Ukrainian postal service has already planned a second stamp to celebrate the sinking of the Moskva, which will be printed in Ukrainian and English. The Ukrainian National Guard has commissioned a press officer, Operator Starsky, to produce regular English-language YouTube updates often filled with sarcastic content, such as the “unboxing” of a vaunted Russian military drone found to be jerry-built with foreign technology and Russian bottle caps, or an exposé of the wreckage of a “Marvelous Russian ‘Flying Tank.’ ” The international comments are filled with affirmations of Ukrainian bravery and vows to increase the domestic pressure for increased aid.

Meanwhile, Russian state sources, such as the Ministry of Defense’s Telegram channel, stake out an entirely different legacy of World War II, choosing solemn comparisons between today’s soldiers and Red Army heroes, and reciting the grim crimes of Ukrainian nationalists against Soviet civilians. However, the Russian state’s inability to tap the rich legacy of Efimov, Ehrenburg, and other socially resonant humor suggests the country’s continued failure to fully justify the invasion, even to itself. Official Russian military humor is either absent or grotesque, for what is Russia’s unofficial yet pervasive “Z” logo for this war if not a mockery of a just cause?

As the war begins a terrible new phase, Ukrainian laughter will likely get more disdainful, as it did in World War II, an evolution that ignored any distinction between “good” and “bad” Germans, and portended future violence. State-sponsored humor has mostly celebrated Ukrainian pluck and mocked Russian ineptness and technological failures, but has avoided relishing Russian death or physical disfigurement. But this could change.

A far worse outcome, however, would be the slow extinguishing of Ukrainian laughter in its defense, which is an all-too-real possibility. Humor thus far has operated in two registers in this war: first, as a buoyant for Ukrainian morale, and second, as an invitation to foreign audiences to see the justness of the Ukrainian cause. If Ukrainians cease laughing, it will mean the collapse of morale and, with it, the resistance itself. And as during World War II, Western leaders will have to consider whether in exchange for laughing alongside Ukraine, they owe more guns and tanks.