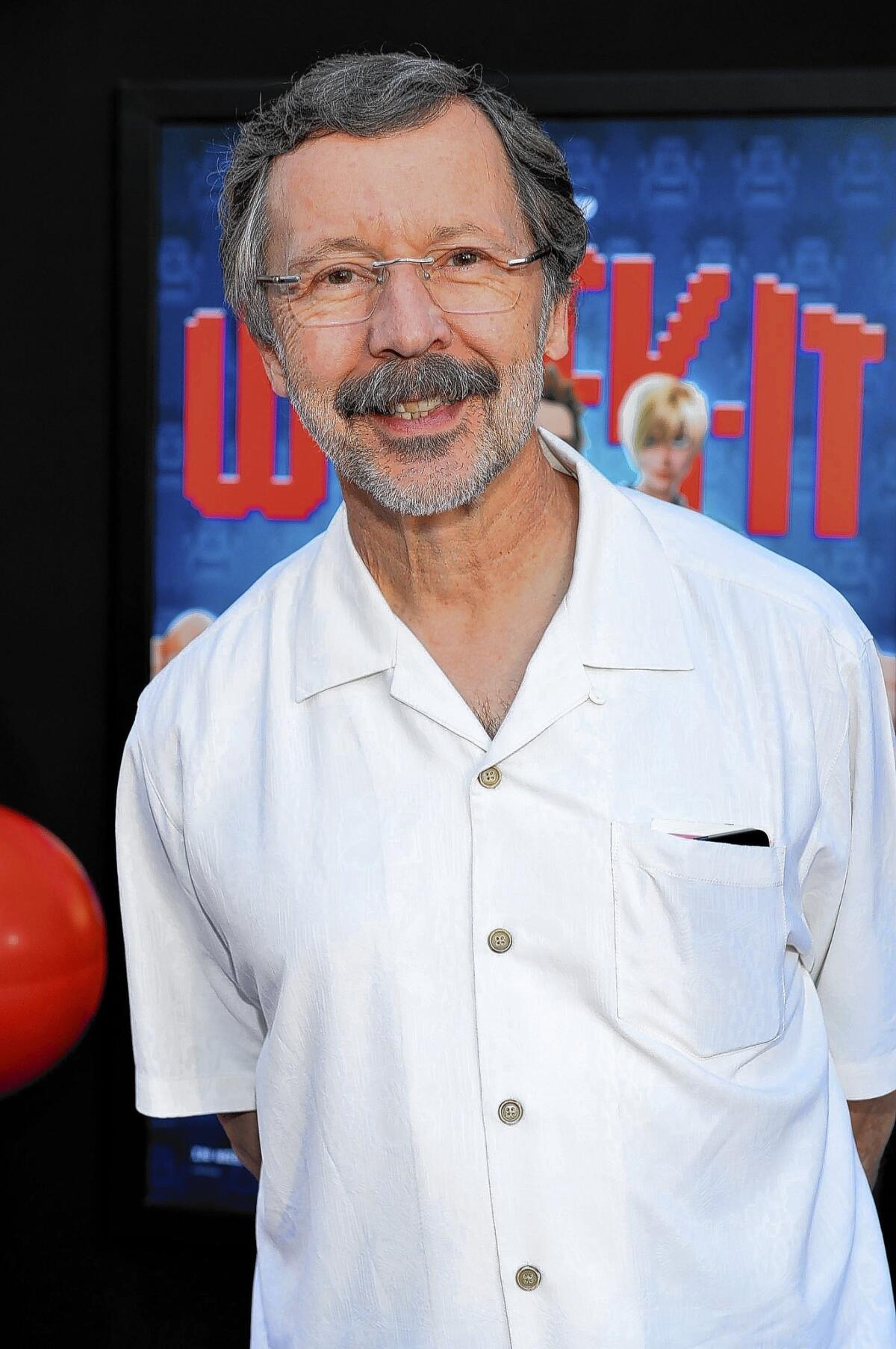

Ed Catmull’s ‘Creativity, Inc.’ is a thoughtful look at Pixar

Animation giant Pixar uses technology only as a means to an end; its films are rooted in human concerns, not computer wizardry.

The same can be said of the new book “Creativity, Inc.,” Ed Catmull’s endearingly thoughtful explanation of how the studio he co-founded generated hits such as the “Toy Story” trilogy, “Up” and “Wall-E.”

Catmull was a 1970s computer animation pioneer (university classmates included Netscape co-founder Jim Clark), but his book is not a technical history of how the hand-drawn artistry perfected by Disney was rendered obsolete by the processing power of machines.

Rather, he uses Pixar’s triumphs and near-disasters to outline a system for managing people in creative businesses — one in which candid criticism is delivered sensitively, while individuality and autonomy are not strangled by a robotic corporate culture.

“Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration,” written by Catmull with Los Angeles writer Amy Wallace, was published by Random House.

Some of the advice flirts with cliche: Staff must be allowed to fail, and so on. But the tips are anchored persuasively in strong examples. The key question of how much failure should be tolerated is not ignored, for instance. For Pixar, the limit is reached when a director has lost the confidence of his or her crew.

The accidental deletion of two years’ work on “Toy Story 2” is a wonderful case study. Catmull insists there was never a witch hunt to identify who typed the simple but catastrophic command into the system.

Happily, a woman working from home unexpectedly had a backup. For Catmull, this is further proof that staff should be allowed to do jobs their own way.

The troubled gestation of “Toy Story 2” almost had fatal consequences.

A late overhaul of the film put tremendous pressure on staff, to the extent that one exhausted artist accidentally left his baby in a vehicle in the company parking lot in broiling heat. The child had to be revived from unconsciousness when the mistake was realized.

Catmull feels guilty about the strain: “Asking this much of our people, even when they wanted to give it, was not acceptable.... By the time the film was complete, a full third of the staff would have some kind of repetitive stress injury.”

He concludes that it is a leader’s responsibility to stop driven and perfectionist staff members from destroying their health and that of others — something that chimes with concerns in the financial world today.

By contrast, “Toy Story 3” was a wrinkle-free production. But when Catmull lauded the crew for this, hackles rose. They took it as a sign they had played it safe, illustrating how the “Failure is good” mantra can have perverse side effects.

In one of the sharper pieces of writing, Steve Jobs, who bought Pixar from Lucasfilm and groomed it for stardom, is likened to a dolphin.

Shouting out harsh criticism was his way of taking the measure of a room, Catmull says: “Steve used aggressive interplay as a kind of biological sonar. It was how he sized up the world.” The Pixar man — whose gentle authorial voice could not be more different — stresses that his late friend and protector’s style softened.

Jobs sold Pixar to Disney for $7.4 billion in 2006. The deal left Catmull president of both Disney’s animation arm and Pixar, roles that he still holds. John Lasseter, another weighty figure in Pixar’s history, became chief creative officer of both entities.

The pair’s challenge was to revive the Disney operation without losing the open and collaborative spirit Pixar had developed.

The recent Oscar-winning success of Disney’s “Frozen” — and the strong showing of “Wreck-It Ralph” before that — suggests they have made great strides in the first of these tasks.

But Catmull’s vivid recounting of the turnaround creates an odd dynamic near the end. The last segment on Pixar’s inner workings tracks a mass brainstorming, called Notes Day, at its headquarters. Catmull bills it as a renewal, but it feels a bit leaden on the page. Maybe Disney has the edge right now.

Adam Jones is an editor at the Financial Times of London, in which this review first appeared.