Recruiting Bill Clinton

How the New Democrats recruited a leader and saved the party after three devastating Republican routs

In the aftermath of the 1988 presidential election, it didn’t take a genius to figure out that the American people weren’t buying what the Democrats were selling. If Democrats wanted to begin winning national elections again, we needed to stand for ideas and beliefs that the American people would support.

We had learned a hard lesson in the last presidential cycle. For all the good things we did between 1985 and the end of 1987, when we got into the presidential year of 1988, it was much like the presidential years of previous cycles. Those of us who wanted to see a different kind of Democratic Party were disappointed.

To bring about real change in the Democratic Party, the Democratic Leadership Conference, which we had founded in 1985 to expand the party's base and appeal to moderates and liberals—had to become a national political movement. That required two things.

First, we needed an intellectual center, because without a candidate to rally around, we needed a set of compelling ideas. Just as it was clear that we needed to paint the mural, it was also clear that we needed to beef up our capacity to paint it. We needed more substantive help. We needed a political think tank with the capacity to develop politically potent, substantive ideas that our elected officials and political supporters could embrace. In January 1989, we created the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI).

The second thing that we needed was to recognize that all knowledge did not reside in Washington. To reach out across the country for ideas and support, we had already begun organizing state DLC chapters. And by the middle of 1992, we had a presence in every state and DLC chapters in half of them, with more than 750 elected officials and thousands of rank and file members. PPI and state chapters gave the DLC critical weapons for the battle to change our party. But we still needed a battle plan.

So we looked at the results of the last six presidential elections to determine why the Democrats had lost.

We discovered that we were losing because middle-class voters, voters at the heart of the electorate, had voted Republican in 1988 by a 5-4 margin. The reason was that they did not trust Democrats to handle the issues they cared about most. In a Time magazine survey a week before the election, voters said that Republicans would do a better job than Democrats of maintaining a strong defense by 65–22; of keeping the economy strong by 55–33; of keeping inflation under control by 51–29; and, of curbing crime by 49–32. Those were the issues that drove presidential elections, and until the perception on them changed, Democrats simply were not going to be competitive.

Armed with this knowledge, we launched a four-part strategy to change the Democratic Party.

Phase one was reality therapy. We believed that Democrats needed to face the reality of why we had lost three presidential elections in a row by landslides so they would not repeat their mistakes for a fourth straight time. So we would tell them.

Second, we had to articulate a clear philosophy, a simple philosophical statement that told voters what we stood for.

Phase three was the development of substantive ideas that made up a governing agenda. That’s why we needed the PPI.

But even having the philosophy, and the governing agenda, in hand, we still stood to be disappointed in the 1992 election as we were in 1988 if we didn’t have a candidate espousing the DLC philosophy as the nominee. Like it or not, a political party is defined by its presidential candidate. So our philosophy and ideas had to pass the market test, and this was phase four of our strategy. In our system, a market test can only come in the presidential primaries, so we needed to find a candidate.

****

A little after four o’clock on the afternoon of April 6, 1989, I walked into the office of Governor Bill Clinton on the second floor of the Arkansas State Capitol in Little Rock.

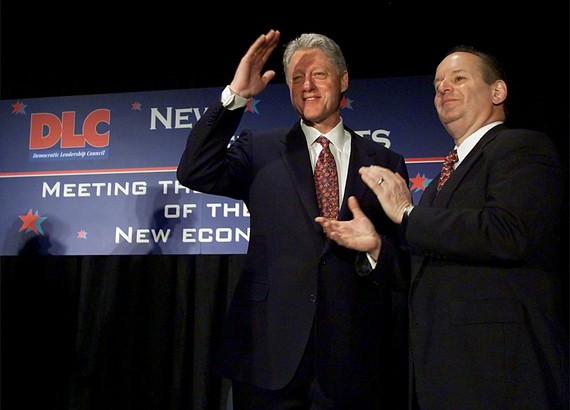

“I’ve got a deal for you,” I told Clinton after a few minutes of political chitchat. “If you agree to become chairman of the DLC, we’ll pay for your travel around the country, we’ll work together on an agenda, and I think you’ll be president one day and we’ll both be important.” With that proposition, Clinton agreed to become chairman of the Democratic Leadership Council, and our partnership was born. With Clinton as its leader, the New Democrat movement that sprung from the DLC over the next decade would change the course of the Democratic Party in the United States and of progressive center-left parties around the world.

The idea of forging a new agenda for 1992 particularly appealed to him. I’m convinced that after he decided against entering the presidential race in 1988, he concluded that the most important thing about running for that office was knowing what you’re going to do for the American people.

We talked for a few more minutes about what our agenda might include. We agreed that the Democratic Party had to modernize and reestablish its sense of national purpose, and that it was important for the party to get on the right side of the security issue. Then he called in a couple of members of the Arkansas legislature to meet me and suggested I join him and a few of his staff members for a drink at a local hangout.

Ever since Clinton had told Chuck Robb in 1987 that he was open to taking the DLC chairmanship, he was my first choice to succeed Sam Nunn. After hearing the response to his speech the year before in Williamsburg and watching him captivate the audience the previous month at the DLC meeting in Philadelphia, I was convinced that he was the best political talent I had ever seen.

But political skill was just one of several reasons I was so determined to make Clinton the next DLC chairman. He was a reform governor and understood the importance of innovative ideas to political success. As he would say in his inaugural speech as DLC chairman, “In the end, any political resurgence for the Democrats depends on the intellectual resurgence of our party. There’s far too much talk about personality in politics and far too little about what we’re going to say and do to make sense to the American people.” Clinton loved to talk about ideas, and he had a striking ability to explain the most complicated concepts clearly.

He was not afraid to challenge old orthodoxies. In the early 1980s, long before I knew him, he and Hillary Clinton pushed cutting-edge education reforms, like pay for performance and public-school choice, against the opposition of the powerful Arkansas Education Association. Speaking about education in his Philadelphia speech, Clinton said the Democratic Party was “good at doing more. We are not so good at doing things differently, and doing them better, particularly when we have to attack the established ideas and forces which have been good to us and close to us. We are prone, I think, to programmatic solutions as against those which change structure, reassert basic values or make individual connections with children.”

Most important, Clinton believed in the DLC philosophy—in the basic bargain of opportunity and responsibility. In his speech on Democratic capitalism in Williamsburg, he demonstrated that he understood the importance of both the private economy and the growth of small business, which he called the backbone of the economy. He recognized the role of government in making sure every American has the opportunity and the tools to get ahead. Clinton was a leader among governors in calling for welfare reform and personal-responsibility measures, including requiring kids to stay in school to get a driver’s license and fining parents who missed their kids’ parent-teacher conferences.

Though Clinton came from a conservative state and knew how to communicate with the moderate and conservative voters Democrats needed to win back, he was also well-regarded among liberals—and so would help the DLC broaden its appeal in all but the most extreme-left parts of the party. Appealing to a broader spectrum of the Democratic Party was important for the DLC, and for me personally. Though the political shorthand had always referred to the DLC as moderate or conservative Democrats, our ideas were really about modernizing liberalism and defining a new progressive center for our party, not simply pushing it further to the right. Coming from the center-left of the party, I was tired of having the DLC labeled as conservative. I decided to call our think tank the Progressive Policy Institute because I thought it would be harder for reporters to label it as the “conservative Progressive Policy Institute.”

Finally, Clinton would strengthen our support outside of the nation’s capital, and as a presidential possibility, he would attract national press.

At the Democratic National Convention in July, presidential nominee Michael Dukakis asked Clinton to give his nominating speech. Convention speeches are always difficult because the crowd is usually not paying attention, but this speech was a disaster for Clinton. It was long and was made even longer because the crowd screamed every time he mentioned Dukakis’s name. The result: It was widely panned. To bounce back, the ever-resilient Clinton went on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show the next week, told a few self-deprecating jokes and then played the saxophone with the band. I knew Clinton was down after the speech, and I sent him a handwritten note: “It doesn’t matter how long you speak or how well you play the sax, just so you’re still part of our team. Just in case you need a reminder, you’ve got an awful lot of admirers—and none greater than your friends at the DLC.”

In offering him the chairmanship, I had gotten a little ahead of myself. When I made my April 1989 trip to Little Rock, I knew Chuck Robb was favorably inclined toward a Clinton chairmanship, but Sam Nunn, who was planning to step down as chairman of the DLC by the fall, was not as convinced. He was concerned that Clinton would be too liberal. That was a complaint Nunn heard from a number of his Senate colleagues when he talked to them about Clinton assuming the chair.

Nunn raised those objections when the DLC board, including Nunn, Robb, Jim Jones, and me, met on July 21 to pick the next chairman—three months after I had offered the job to Clinton. I told the board that a number of members had expressed an interest in the chairmanship, including Clinton, Virginia Governor Gerry Baliles, Florida Senator Bob Graham, and Tennessee Senator Jim Sasser. But, assuming we could work out the logistics—and I was sure we could—I preferred Clinton.

Robb argued strongly for Clinton. Nunn, who argued Clinton might run for president and not give the DLC enough attention, finally agreed. As we walked together back to the Russell Senate Office Building after the meeting, Robb said to me: “If Clinton spends the next four years running for president on our stuff, we’ll be all the better for it.”

Once the board agreed, I thought it would be a simple matter to schedule an official transfer of the position. Clinton had told me he would take the chairmanship in Little Rock, but we still had to set a date for him to assume the gavel. One possibility was to have Nunn pass the gavel to Clinton at a Washington issues conference we had planned for November, a few days after the election. But as I soon learned, with my friend Bill Clinton nothing is ever simple or easy.

He did come to the November 13 conference and once again was a big hit, but he said he wasn’t quite ready for the transfer to occur. And so it would be for the next four months. He would repeatedly tell me that he was going to take the job, but he was trying to decide whether to seek another term as governor in 1990 and that decision could impact when he could take over the DLC. So 1989 turned into 1990, and Clinton had yet to take up the reins.

Nunn was getting antsy and kept pressing me to get a date from Clinton. He had met with Clinton in December of 1989 and Clinton had assured him, too, that he would take the chairmanship. The obvious time to make the change was at our national conference scheduled for New Orleans on March 22, 1990. But I had no guarantee from Clinton. Finally, in frustration on February 23, a month out from New Orleans, I wrote a “personal and confidential” memo to Clinton and personally handed it to him at the Hyatt Hotel on Capitol Hill where he was attending the annual meeting of the National Governors Association. My message was blunt:

We are getting past crunch time on the DLC chairmanship. There are a number of strategic and procedural decisions we simply have to make before the end of the day today so that we can put them into place by the New Orleans Conference.

I realize your personal situation is complex, but at the DLC, we’ve run out of time. If you can’t make a 100 percent commitment to take the DLC chairmanship this week, I have to recruit someone else.

I wrote that he was my choice and that Chuck Robb and I “put our necks on the line to get board approval,” but that was the previous July and we were still hanging.

Sam Nunn has taken his meeting with you in December and your statements to me in early January as a commitment that you would take the chairmanship, and is expecting to pass the gavel to you in New Orleans. But every signal I’ve gotten from you in the last month indicates you’re still up in the air. That ambivalence is a killer for us as we prepare for New Orleans.

I believe you are the right person for the DLC job—and the DLC job is the right job for you. We have the opportunity to redefine the Democratic Party during the next two years. If our efforts lead to a presidential candidacy—whether for you or someone else—we can take over the party, as well.

We are poised to expand the DLC effort exponentially. But our New Orleans Conference is a critical juncture—and if we are to turn the DLC effort into a full-blown political movement, New Orleans is the best launching pad we are likely to have this year. We’re a month out, and we simply need to put some things in place now or we will lose that opportunity.

Clinton looked at the memo and then said, “If I don’t run for reelection, then I’m going to have to make at least $100,000 a year.” A hundred thousand a year probably seemed like a lot of money for Clinton in 1990; his gubernatorial salary was just $35,000 a year—among the lowest of all governors. And if he left the governor’s mansion—he used to quip that he spent most of his life in public housing—he would have had to pay for a place to live for the first time since he was out of office in 1981 and 1982. I told Clinton that I’d be delighted to pay him $100,000 a year to be a full-time chairman of the DLC.

After going back and forth about whether to run for a fifth term as governor, he was scheduled to make an announcement on March 3. Craig Smith, Clinton’s aide who often traveled with him on DLC trips, called me in the middle of Clinton’s announcement speech to tell me Clinton was not running for reelection. He called me back a few minutes later and said he was indeed running. “He talked himself into running in the middle of his speech,” Craig told me.

After months of pondering, Clinton decided to run for reelection as governor and become chairman of the DLC. Nearly a year after our Little Rock meeting, at the DLC’s Annual Conference in New Orleans on March 24, 1990, Bill Clinton became the DLC’s fourth chairman. Calling Clinton a “rising star in three decades,” Sam Nunn passed him the gavel. Nunn quipped that when the DLC was created “we were viewed as a rump group. Now we’re viewed as the brains of the party. In just five years, we’ve moved from one end of the donkey to the other.”

Under Bill Clinton’s leadership, the DLC would cement that image and redefine the Democratic Party along the way.

This post is adapted from The New Democrats and the Return to Power.