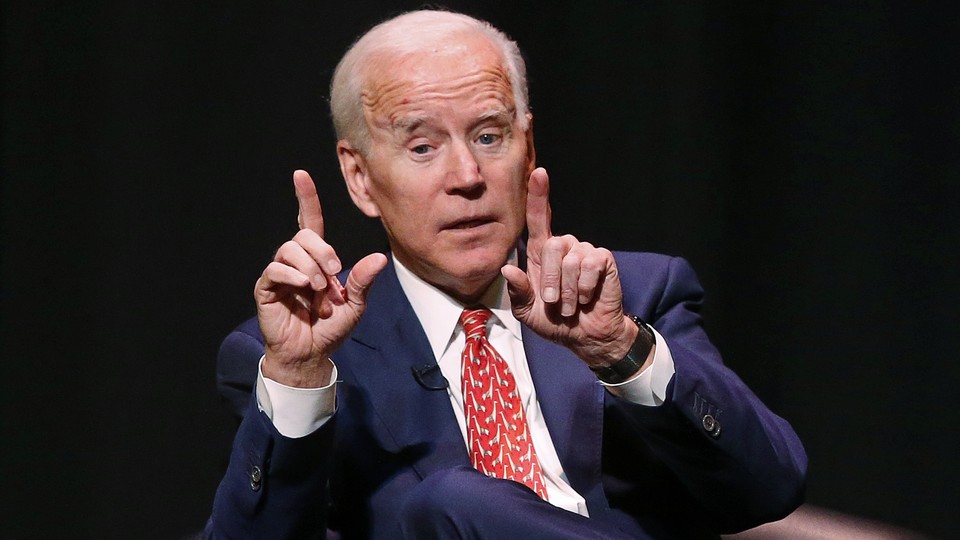

Biden’s Anguished Search for a Path to Victory

As he contemplates a 2020 run, the former vice president is focused on whether Democrats will support a centrist septuagenarian.

Joe Biden reliably blows through every public and private deadline for making a decision about running for president. But he’s giving everyone he’s seen in recent weeks the feeling that he’s very close to saying yes.

The urgency of Biden’s planning has stepped up since the beginning of the year and serves as a window into the complexity of this moment in American politics, with Donald Trump halfway through his chaotic first term and a diverse and progressive field of Democrats already lined up to run against him in 2020.

Top positions for a campaign have been sketched out. Donor outreach has accelerated, with Biden himself telling staff at some events to write down the names of people who say they’re eager to help. A list of potential “day-one endorsers” among elected officials has been prepared. Basic staff outreach is happening. Biden has even joked to people that he’s upped his daily workout to get in shape.

“I have been told that if it happens, I need to be ready to go with a moment’s notice,” said one person who’s been in conversations with Biden’s top aides.

Skepticism persists, fed by donors who are wondering why they haven’t heard anything, and operatives who others in the field assumed Biden would have locked down by now are still shopping around for other candidates.

Biden pulled the plug at the last minute in 2015, and some of those closest to him warn he still may this time.

Biden has said as much himself.

In January, he went to the New York offices of BlackRock, the major investment firm, for a meeting with Larry Fink, the CEO. They talked about the state of the world and the country, about what’s going on in the markets. Toward the end, Fink said to Biden, “I’m here to help,” according to people told about the conversation.

Biden took it as an offer to sign on with the campaign.

“I’m 70 percent there, but I’m not all the way there,” Biden told Fink.

That same 70 percent line has been circulating among Biden allies for weeks: This looks like it’s happening, but don’t write off the 30 percent chance that it doesn’t. In that time, people who’ve spoken with Biden and those around him say he is still anguishing over both whether there’s a path to victory and whether running is the right thing to do for those closest to him, knowing that his record would be attacked and sensitive questions about his family would be aired in public.

“His heart is saying, ‘Go. It’s the thing you’ve always wanted,’” said one person who’s been in touch with Biden’s staff. “His head is assessing whether there’s an opening.”

Trump worries and offends Biden, and he feels a sense of duty to the government and the country to get things back on track. He fears that other Democrats can’t beat Trump and aren’t prepared for what it would be like to take over the government in his wake. Notably, no other announced or prospective candidate has any foreign-policy experience.

But over two presidential runs, and an additional two times he came very close to jumping in, Biden has struggled to put together effective campaign operations. This time around, multiple top Democrats who express deep affection for him say they also worry that he is underestimating how hard a campaign would actually be to pull off—let alone the damage it could do to his reputation or what the exposure would mean for his family.

Biden is weighing his decision without any official polling or focus groups. He and his team have been talking with John Anzalone, a Democratic pollster who worked for both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. His ties go back to 1987, when he worked as an organizer in Iowa for Biden’s first White House run.

In several meetings recently, Anzalone laid out the realities of the Democratic-primary electorate based on public polling and election results from 2016 and 2018, concluding that it’s not as left-leaning or as young as it’s often portrayed. Biden has shown the document to other visitors, trying to decode what appetite exists for a centrist who is unapologetic about wanting to work more with Republicans, and who will turn 78 years old two weeks after Election Day 2020. Anita Dunn, who served briefly as White House communications director for Obama and is a Biden friend, has also been advising informally.

“Democrats netted 40 seats in the midterms and did so with a lot of candidates that pundits in D.C. would dismissively call ‘center left.’ But the results suggest that in fact there’s a very strong case to make that bridge-building progressivism is exactly what Democratic voters want,” said one person familiar with Biden’s thinking.

Bill Russo, a spokesman for Biden, declined to comment on his political deliberations.

Biden and his aides think Bernie Sanders, who is a year older, might help neutralize the issue of Biden’s age. Sanders is considered likely to join a progressive field that includes Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand, Cory Booker, and possibly Sherrod Brown sometime soon. A Sanders candidacy would likely encourage Biden to run because he doesn’t agree with the Vermont senator’s policies and thinks they’re losing politics.

In a primary, Biden and his advisers believe, all those left-tilting candidates would divide support and leave him with a sizable number of more moderate voters.

“We’ve got a little bit of our own lane. We just need to go own it,” said a third person who’s been in touch with Biden’s top aides. “He’s well aware that this isn’t going to be easy, he’s going to have to fight for it, but I don’t think he’s viewing this thing through the lens of matching up against any one candidate.”

In late January, Biden’s aides made this case in talking points they circulated to allies who were being asked about his plans. “Joe Biden is someone who can reassert what our core values are. He can answer the big questions facing this country with real moral authority,” reads one section.

The campaign manager, if there is a campaign, would be Greg Schultz, Biden’s longtime political director and currently the head of his American Possibilities PAC. The communications director would be Kate Bedingfield, his last communications director at the White House. Steve Ricchetti, his chief of staff at the White House, who’s stayed with him over the past two years, will serve in a similar role for the campaign, assisted by the longtime political consultant Mike Donilon.

Ricchetti and Donilon have told people that they are now as close as they can get without having the final word from Biden. One major focus: how to quickly build a base of small-dollar donors, which is of particular concern because Biden has always struggled with fundraising and doesn’t have a large existing email list.

Those reading tea leaves for his wife, Dr. Jill Biden, think she’s on board. She has been notably receptive to taking on public events and is preparing for the rollout of her own book in May. Last Monday night at an event in Florida, his daughter Ashley was spotted reacting excitedly when he told a story onstage of her asking him whether he was going to run, and saying he was nearing a decision.

But even as informed speculation leads to people guessing about where the campaign headquarters would be or dates they think might work for an announcement, big questions remain.

Among the biggest: How would he answer for his role in the Anita Hill hearings; for backing the 1994 Crime Bill, with harsh sentencing guidelines; and for supporting corporate-tilting financial legislation during his decades representing Delaware in the Senate? Still, Biden and his team look at the midterm results and think they’re proof that this may be more of a moment for him than people realize. More people won elections in November talking about protecting Obamacare, for example, than calling for Medicare for All.

Then there’s the Obama endorsement question. The two remain friends and speak on the phone. Even as the former president counseled other Democrats looking at presidential runs, he has generally avoided the topic of 2020 with Biden, and Biden hasn’t brought it up.

But if Biden runs, he’ll be running in part on the Obama-Biden record, which would raise the question of an endorsement. If Obama did endorse or even just strategically praised his former VP, he’d be putting his thumb on the scale in a way that backfired in 2016, when he did it for Clinton. Obama advisers stress that the former president thinks highly of Biden. But they deflected the question of whether this admiration would lead to an endorsement by saying they didn’t want to get ahead of the former vice president’s decision-making process.

Biden, meanwhile, is not assuming he’d get an endorsement, especially with Obama publicly and privately stressing that he does not feel like he should be the one deciding the future direction of the party.

Biden’s team has also been weighing how, if he runs, he’ll position himself within the field: as a statesman and party elder, but eager to avoid any of the inevitability that happened with Clinton. He would be attempting to run a first-among-equals campaign, which Biden allies think might be helped by all those in the Democratic chattering class who doubt he could pull it off in a changed party and political environment.

The people who believe in a Biden candidacy think it begins with his working- and middle-class white base. He also has African American support he earned from being part of Obama’s team, hero status within the LGBT community for jumping out front in support of gay marriage, and a connection to many young people nostalgic for the presidency they grew up with.

For now, even those in the inner circle wait, while the core fans hope. An email list of about 60 diehards that was active during the days of the 2015 Draft Biden effort recently lit up again, with people checking in to say that they’re still around and ready to go. In Iowa, there’s even an old staffer from his 2008 campaign who’s been using Facebook to reach out to supporters on his own and collecting résumés, just in case.

“I don’t want to make the mistake of getting hopes up until the vice president makes a statement. In 2015, Biden supporters here waited and waited, and ultimately he didn’t run,” said Marty Parrish, who was Biden’s campaign IT coordinator in Des Moines. “I’m not in the vice president’s inner circle by any means, but if and when he makes an announcement, I would expect someone will reach out to me.”