Editor Jen Johnson "has a particular interest in helping students craft well-written doctoral research, from the sentence level up." Check out her previous posts, on everything from social change writing to the assumptions in a study.

Showing posts with label Tech Tips. Show all posts

Paraphrasing Generators Impede Learning

The most common questions I hear from Walden students are about how they can save time. Specifically, students often ask whether they can use X program to help them with their writing. The programs students are asking about can vary, but common ones I hear about are APA reference generators, spell check, and Grammarly. The question is understandable: You are busy students, balancing work, family, and school, and you have limited time. If there’s a way to save you time, I’m with you!

Unfortunately, my answer to this type of question often disappointments the students asking it. Rather than a whole-hearted endorsement, I explain that potentially the program they are asking about could be useful, but that all writers need to be careful that they are using these programs judiciously. I go on to say that English grammar, academic writing, and APA are complex and often dependent on context, which computer programs sometimes can’t understand. My recommendation to these students, then, is that if they must use these programs, use and review their results carefully.

Another Chapter in the Story: Paraphrasing Generators

That seems like the end of the story, right? Well, not quite. My standard response to this question changed slightly when I learned about a new type of program promising amazing results to academic writers: paraphrasing generators. There are many versions of paraphrasing generators, but all of them promise quick and easy paraphrasing that avoids plagiarism. The problem with these paraphrasing generators, however, is that they aren’t really paraphrasing generators—they are really synonym generators, which isn’t true paraphrasing.

Let’s take a closer look at why paraphrasing generators aren’t really paraphrasing at all. Paraphrasing is a difficult academic writing skill because it’s complex. Strong paraphrasing requires critical thinking where a writer represents a source’s ideas in their own voice. What makes a paraphrase in your own voice? Three things: (1) focus on the key information needed for the context of your paragraph; (2) use of your own word choice; and (3) use of your own sentence structure. Complex, right?

Paraphrasing generators only address one of these three parts: swapping out words with synonyms. They can’t determine the most relevant information to include, how it fits into the context of your paragraph and your own ideas, and how to rephrase the ideas into your own voice, all essential parts of a paraphrase.

The other issue is because paraphrasing generators rely on synonyms, the result can be strangely worded at best and unintelligible at worst. Synonyms are tricky things; most of the time writers must choose synonyms carefully to avoid changing the sentence’s meaning. Using synonyms judiciously is important when using even one synonym in a sentence, but entire sentences of synonyms become so unclear that the original meaning is entirely lost.

Let’s Take a Look: A Paraphrasing Generator Result

Let’s take a look at these issues in practice so we can see the actual result of using a paraphrasing generator. Here is an original quote and the result of a paraphrasing generator. Read both carefully, then ask yourself: Does the result from the paraphrasing generator accurately reflect the original quote’s meaning? Does it sound like a new, original voice?

Original Quote: "Online teaching observations are valuable tools for documenting and improving teaching effectiveness" (Purcell, Scott, & Mixson-Brookshire, 2018, p. 5).

Result from Paraphrasing Generator: Web based showing perceptions are profitable instruments for reporting and enhancing adequacy.

Hopefully you’ve generated some ideas in response to my questions above. Here are my responses:

- The result from the paraphrasing generator changes the meaning of the original. Where the original quote refers to “valuable tools,” the paraphrasing generator says “profitable instruments.” Something being valuable is very different than being profitable, which has connotations of monetary gain that valuable doesn’t.

- The paraphrasing generator also doesn’t make sense! Where the original talked about “observations,” the paraphrasing generator says “showing perceptions.” If you’re like me, you’re probably wondering what “showing perceptions” even are. Additionally, the phrase “instructing adequacy” from the paraphrasing generator isn’t clear.

- The paraphrasing generator doesn’t create a new, original voice because it relies on the original quote’s sentence structure. If we were to diagram these two sentences—marking out their grammatical structure—they would be exactly the same.

As you can see, the paraphrasing generator doesn’t have very good results. But beyond that—beyond all of the problematic aspects we’ve discussed so far about paraphrasing generators—there’s one final drawback:

Programs like paraphrasing generators get in the way of your learning! They offer a quick solution, but this short-term gain impedes long-term progress. If writers use paraphrasing generators, they aren’t engaging with the research they are reading, learning how to put it in their own voice and developing their paraphrasing skills.

Paraphrasing generators have a certain appeal, especially if writers are looking to save time or they believe their promises of avoiding plagiarism. However, they are much more problematic than the other programs students often ask me about. While Grammarly, spell check, and APA reference generators can be used cautiously and still be helpful, my conclusion? Paraphrasing generators should be avoided altogether; they simply have too many drawbacks to be helpful to academic writers.

Beth Nastachowski is the Manager of Multimedia Writing Instruction in the Writing Center. She joined the Writing Center in 2010, and enjoys helping students develop their own voice as writers through webinars, residencies, and multimedia resources. She is also Contributing Faculty for Walden's Academic Skills Center (ASC).

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Speech-to-Text: Prewriting by Speaking

Let’s face it, scholarly writing can be frustrating—sometimes you might face writer’s block, sometimes you might face issues juggling school, work, and other responsibilities, and sometimes, yes, sometimes, you just don’t feel like writing. Period. I don’t mean just the mental tasks involved with scholarly writing, but the physical one too (so much time staring at a screen and typing!).

That said, one of the hardest parts about being in a position as such can be when you are beginning a writing project. For this blog post, I will be discussing how you might use your computer’s speech recognition software to enable Microsoft Word’s speech-to-text features for prewriting (i.e., brainstorming, freewriting, journaling, creating an outline, or otherwise organizing your thoughts). Since this post is more theoretical, I won’t be discussing the technical “how” of using MS Word’s speech-to-text, but rather the “why.” If you have questions about using MS Word features and functions, you can contact the Academic Skills Center's Microsoft Word tutoring team. I also found this tutorial on setting up speech recognition on my computer helpful.

My own introduction to using MS Word’s speech-to-text was as a graduate student. More specifically, as a graduate student, I wrote three twenty-five page papers per semester (and that’s not including, of course, discussion board posts and other shorter assignments). Over the course of my masters and doctoral studies, this clocks into about fifty twenty-five page papers. It’s easy to believe how sometimes I got tired of writing but still needed to keep the momentum up. So, I started to use speech-to-text as a way to both get myself motivated to write and to help with the process of writing.

Brainstorming, Freewriting, and Journaling

I sometimes used speech-to-text just to brainstorm ideas for paper topics. For instance, when I wasn’t sure what I wanted to focus a paper on, I would “talk through” ideas on paper without having to sit down and write. Similarly, other times I would have a loosely articulated idea and I would use speech-to-text as a way to freewrite, or journal, to flesh my idea out more. For me, the physical act of writing could sometimes lead me to more writer’s block issues, making me feel like I had to come up with something and start drafting. Thus, speech-to-text allowed me to just freely brainstorm, freewrite, or journal while simultaneously keeping notes, taking some of the pressure off and leading to actual drafting as opposed to more writer’s block.

Creating and Outline and Organizing Thoughts

In addition to helping me brainstorm and flesh out ideas further, speech-to-text was also helpful when I wanted to use an outline to draft those larger papers. For example, those longer course papers required a lot of planning, and outlining provided a way to layout and manage my argument which took some of the head work and time out of the process. Thus, for me, speech-to-text helped with time management. Like many students, I had several other responsibilities outside of my coursework, such as teaching, so having a program that helped me with time management, to include cutting down my typing and drafting time, was a huge plus. To be clear, I could work on an outline while making dinner or in-between teaching sections of classes. Then, when I was ready to start drafting, the process went more smoothly because I there was less struggle with starting up.

Motivation

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the ability to use speech-to-text in Microsoft Word to brainstorm, freewrite, outline, and organize my ideas helped to keep me motivated to write. Rather than sit down in front of my computer and feel blocked about what I wanted to write about, struggle with fleshing out my loosely formed ideas, or face issues with time management and drafting, I could use speech-to-text to keep me motivated to write because it helped break down the process of drafting in ways that sitting at a computer often didn’t. For me, sometimes the act of writing itself creates writer’s block because I fail to see the trees amongst the forest. Taking some of the typing time out of drafting relieved some of the pressure and helped motivate me when it was time to sit down and start drafting.

Next time you are faced with a writing assignment—or maybe even the masters thesis or dissertation—you might try using your computer’s speech-to-text programs to help with brainstorming, outlining, and keeping you motivated. Whether you use speech-to-text or not, I do recommend prewriting as a way to support a smooth writing process. As my dissertation chair once said to me—slow and steady wins the race!

Let us know if you’ve tried speech-to-text for prewriting in Microsoft Word. How did it go? Have you used any other technology for prewriting? Share in the comments below!

Veronica Oliver is a Writing Instructor in the Walden Writing Center. In her spare time she writes fiction, binge watches Netflix, and occasionally makes it to a 6am Bikram Yoga class.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Technical Tips for Longer Writing Projects

Monday, June 19, 2017 Capstone Writing , Dissertation , Tech Tips , Walden University , Writing Process No comments

I admit, I definitely have a love-hate relationship with MS Word; while there are so many options for making the word processing simpler and ensuring the finished document looks slick, there always seems to be some quirk or default in the system that makes me feel more like I’m wrestling with the document rather than revising it.

Once I started to dig into the various functions available in MS Word and got over some of my fear and anxiety about the software, my relationship with MS Word improved a lot. Now I recommend many of the functions I used to nervously avoid, and there are several options I could not do without when working with longer documents.

Word Support

Remember, there are people out there whose job it is to help. Playing around with software or new functions you aren’t used to using can feel intimidating, and sometimes you don’t even know what you don’t know or what to ask. Take some time to familiarize yourself with the different MS Word resources available through the Academic Skills Center, and you will be surprised at what you could learn that will help you later on.

If you scan down the menu to the left of the page and review the resources available at some of those links, you may even recognize solutions to problems you have encountered before. (I did not even know what a dot leader was until I had to learn how to fix them.) Plus, you will have a better idea what Word can do and how you can use it to compose your manuscript.

The Academic Skills Center offers one-on-one support, and you can either make an appointment or send your questions to WordSupport@waldenu.edu.

Moving Swiftly yet Carefully in Longer Documents

Beyond the formatting tools are the specific editing functions in MS Word. While you are not required to use it in your own revision practice, all Walden students should be well-versed in how to use Track Changes and the different options for viewing those changes in your document. Your faculty (such as your chairperson and doctoral committee) will use these functions to give you feedback on your drafts, and if you do not know how to view their feedback or incorporate their changes, this can cause frustration on all sides.

I cannot overstate the usefulness of the editing functions of Find and Replace. You may want to use the Replace function less frequently (the “Replace all” option can lead to some confusing and ungrammatical results if you do not read over everything carefully first), but Find will be your friend every time.

Scrolling through a document can get tedious, not to mention hard on the eyes, and printing out your work and reviewing a hard copy will not guarantee you catch every instance of a word or phrase. The Find function (which you can access with the keyboard shortcut “Ctrl+F” on a PC or “Command+F” on a Mac) lets you navigate through your document with the greatest of ease and ensures you locate everything you are looking for (provided you spelled it correctly…).

You can use the Find function to update verb tenses, check for acronym or abbreviation use, and locate the first time you cite a specific source so you know when to use the abbreviation et al. Best of all, you can quickly confirm whether or not your citations have corresponding reference entries listed at the end of the document and whether you have only included reference entries for those sources you directly cited. (Trying to check for this without the Find function could take hours when you are dealing with something the size of a dissertation or doctoral study.)

The Limits of Software’s Magic

You still want to avoid relying too heavily on software options to generate your draft. Some students use citation management software, for example, to help keep track of their reference and citation information. None of these systems is perfect, unfortunately, and their adherence to APA can range from the merely imperfect to the terrible, so make sure you know APA well enough to proofread for errors, and try to avoid using a system that does not let you add your own changes easily.

Do not be afraid to experiment with technical options for revising and organizing your document. If you label files clearly and save often, there is nearly no mistake you cannot undo, so be brave. If, for example, you replace the wrong thing or delete something you meant to keep, you can always undo it and move on. The more practice you have working with the different technical options available to you, the more you can revise like a professional.

Lydia Lunning is a Dissertation Editor and the Writing Center's Coordinator for Capstone Services. She earned degrees from Oberlin College and the University of Minnesota, and served on the editorial staff of Cricket Magazine Group.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

A Writing Center Review: Recite Reference Checker

Managing and updating citations is an arduous, but critical, part of the scholarly writing process. These tasks can be particularly vexing for capstone writers because their work is lengthy, undergoes so much revision, and demands precision, accuracy, and correct formatting. Today, I will provide some perspective on a tool that might be helpful to Walden students, particularly students in the process of writing their capstone studies. The tool is Recite Reference Checker.

Many students are familiar with citation managers such as EndNote, Zotero, RefWorks, and Mendeley. These tools allow you to create a database of sources, from which you can compile citation information and automatically create in-text citations and reference lists. You can annotate research articles as well as create libraries for specific projects. For many individuals and those working on collaborative projects, these tools are useful at all stages of the research process, from writing a literature review to proofreading for publication.

However, Recite is different from a reference citation manager in that it is a citation checker. Its tagline is “Reference Checking Made Easy.” In contrast to citation managers, this is a tool that you would probably find most useful when proofreading your study before your defense or submission to the URR and ProQuest.

Recite is currently free as it is undergoing Beta testing. Its developer, 4cite Labs, plans to introduce “very competitive pricing” after testing is complete. All you need to use it is a Google account. Another plus for Walden students is that it is compatible with APA style, one of the two citation styles Recite supports.

User Experience: How Recite Worked for Me

To use the service, you login in using your Google account on Recite’s website. Then, you upload your own document. I recommend uploading your full study, as opposed to an individual chapter or section, as the software checks your in-text citations against your reference list.

Recite will first show you a list of all in-text citations from your document. The output is color-coded. Dark blue indicates that your citation correctly matches a reference entry. Yellow indicates a possible match while red indicates no match.

|

| Demonstration of Recite's Color Coded Citation Checking |

The software also compares your citations and entries to literature in its databases and suggests possible errors. For example, you may have a wrong name or, for a source with multiple authors, you might have authors out of order. Recite will show you an entry that it thinks is correct. That way, you can assess whether your citation and possible reference entry need to be changed. The software will also tell you when it can find no references for an author or year.

Another positive is that Recite checks your citations and reference entries and tells you about possible APA errors. For example, in one of your sentences, you might include “Smith et al.” as an author in a citation. If this work only has two authors, Recite can tell you that this is an invalid use of “et al.” Recite will also go through your reference list and check whether your entries are correctly formatted in terms of APA. It will show you places for you need to include an ampersand or modify your punctuation, for example.

Evaluation: Is Recite Right for Walden Capstone Writers?

With its integration of APA and its ease of use, Recite seems like a helpful tool for capstone writers. Like any tool, however, Recite may provide you with inaccurate reference or formatting information. You cannot use it as an alternative for double-checking your source information and formatting. If Recite points out a possible mismatch between your reference entry and what it has in its database, you should still double-check your PDF or printout and confirm whether your entry needs to be corrected.

Likewise, if Recite points out a possible APA error (e.g., an ampersand should be used instead of “and” in the author element of a reference entry), you need to be able to determine whether this is, indeed, an error. There really is no shortcut to developing your own APA proficiency as a capstone writer. That is why we offer so many APA resources on our website.

You can test Recite for yourself by either uploading a document or by reviewing the markup on a demo paper on its website. Be sure to read Recite’s terms of service and privacy policy if you decide to use it. Also, keep in mind that Recite stores your document for a “short amount of time,” but the company says this is temporary, while the software is Beta.

Let us know in the comments box whether you have used Recite and what you think about it.

Tara Kachgal is a dissertation editor in the Walden University Writing Center. She has a Ph.D. in mass communication from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and teaches for the School of Government's online MPA@UNC program. She resides in Chapel Hill and, in her spare time, serves as a mentor for her local running store's training program.

.png)

Never miss a new post; Opt-out at any time

Tech Tip: How to Find DOIs for Multiple Articles at One Time

This tech tip will teach you how to find the DOI for multiple articles at one time using CrossRef. I shared this trick at a recent virtual residency, and it was a big hit with students. Who doesn’t like to save a little time?

First, prepare your reference list.

Create an APA-formatted reference list with your electronic journal article entries. Do not use hanging indents, though. You’ll need to eventually, but CrossRef won’t accept that formatting.

Next, visit CrossRef

1. Go to https://doi.crossref.org/simpleTextQueryThen, format the entry

After submitting your reference entries, CrossRef will return your list with any DOIs it has found in red text, as in the following example:

Clark, D., & Roayer, H. (2013). The effect of education on adult mortality and health: Evidence from Britain. The American Economic Review, 103(6), 2087-2120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2087

CrossRef recommends using the doi as it is returned, with the http:// opening. However, in APA style, using either the full http:// address or removing the "http://dx.doi.org" and starting it off with doi: is acceptable. If you use the http:// version of the doi, remember to deactivate the hyperlink in Word.

Copying the CrossRef returns into your reference list is fine, but note that the formatting will change. To put the above example entry into APA style, you would need to:

Copying the CrossRef returns into your reference list is fine, but note that the formatting will change. To put the above example entry into APA style, you would need to:

- Deactivate the hyperlink

- Double space the lines

- Create a hanging indent

- Italicize the journal title and volume number

So, your final reference entry would look like this:

Clark, D., & Roayer, H. (2013). The effect of education on adult mortality and health: Evidence from Britain. The American Economic Review, 103(6), 2087-2120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2087

That's it! Now when your reference list contains multiple electronic journal articles, you can search for all the DOIs at one time..png)

Anne Shiell is a writing instructor and the coordinator of social media resources at the Walden Writing Center. She also produces WriteCast, the Writing Center's podcast.

|

Get new posts in your email inbox!

|

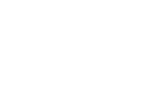

One App Worth Having: A Review of the APA Concise Dictionary of Psychology App

|

| Image © APA, 2013 |

When it comes to technology, I am what you might call old school. For example, while I started keeping a blog ages ago—way back in 2007—I still get cranky whenever Blogger decides to “improve” the site and services, because it means I have to adjust my own familiar, comfortable processes to the changes. And—dare I admit this?—I just sent my first text message ever about six months ago, using my old flip-style cell phone, which is almost never on because I never remember to charge the battery.

I am almost daily made aware of my technological hang-ups by my husband, who is pretty much the exact opposite of me. While I typically scorn what I call “bells and whistles” (who needs a GPS device when you’ve got a real map, after all?), he has a serious appreciation for all the latest developments. To illustrate: On my husband’s nightstand rests a slim Kindle e-reader, clad in a leather case; on mine, a stack of no fewer than 10 books, forever in rotation. He once persuaded me to read a screen or two of text on his Kindle, and while I appreciated its novelty and portability, I am happy to report that I still prefer the heft and feel of a real book in my hands over the convenience of a mobile device. Maybe it’s the writer in me, or the college English major, or the girl who spent all her childhood summers slouched against the stacks in the local library, but no e-reader will ever give me the same reading experience as a real, live, honest-to-goodness book.

That said, I’ve recently been convinced that there are times when the e-version of a book might be just as good, if not better, than the original print. A case in point: The American Psychological Association (APA) now offers a mobile version of its 583-page APA Concise Dictionary of Psychology (APA, 2008). When I heard about this app, I borrowed my husband’s smartphone to investigate. Here’s what I discovered: At $30, the app is slightly less expensive than the print version of the dictionary, but with the same content of more than 10,000 definitions and with a few capabilities that the print version cannot offer. For example, the app allows the user to search by keyword or to simply browse terms, and it offers links to other terms within definitions. To experiment, I searched for Freud and got the result Freudian slip, the definition for which provided a link to the phrase slip of the tongue, which led me to the term spoonerism. In addition to these basic search and browse functions, the app provides search history and the ability to add notes about definitions and mark terms as favorites. It also offers the Historical Figures in Psychology listing available in the print version, along with other features unique to the app version, including Word of the Day and Psychologist of the Day (I got cocaine dependence and Lev Vygotsky one day, resolution and John Hughlings Jackson the next).

In sum, this app may be a good resource for students who like the convenience of having a reference work readily available on their mobile phone, without the need to tote around a 2-pound text. And if you’re like me, an added bonus is the extra room the app leaves in your book bag for those treasured books you cannot bear to read in any other form.

A final note: If you are interested in the app version of the dictionary, know that you will need to buy the full version; the free trial version is little more than a teaser, offering a limited selection of terms and no access to the Word of the Day, Psychologist of the Day, and other special features.

For more information about both the print and mobile version of the APA Concise Dictionary of Psychology, visit APA's website.

Mapping Your Mind With Bubbl.us

I am not a visual learner. That’s what I told myself, anyway, when studying for college exams with a friend and attempting to make sense of the crazy bubbles that comprised his history notes. He tried to convince me that the mess of scribbles he called a “mind map” was an excellent way of note-taking, but I stubbornly stuck to my chronological, college-ruled list.

A mind map begins with a key concept or idea written in the center of a piece of paper or electronic space, and the idea is usually enclosed in a bubble. Related ideas, also in bubbles, branch out from that center idea. As the writer adds more and more ideas, making additional branches and sub-branches, the writer can also use lines or arrows to connect ideas. I realized the beauty of those interconnected bubbles years later when, older and wiser, I tried mind mapping for a graduate school assignment. If I had used a mind map back in college and been able to better visualize the relationships between the events, people, and social movements that I was studying, I might have scored better on that history exam.

To create a mind map, you can use good old pen and paper or a free electronic mapping tool like Bubbl.us, which allows you to color code your ideas and easily add, delete, and rearrange bubbles. I’ll use screenshots from Bubbl.us here to show how a mind map begins and develops.

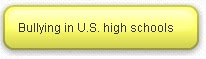

So, let’s say you’re writing a paper on bullying in U.S. high schools. This main topic goes in a bubble in the center of the page:

Next, start branching off of that central bubble with related ideas. What comes to mind when you think about bullying in U.S. high schools? What do you know from course work, preliminary research, or personal experience? For example, the topic might make you think about prevention programs, effects of bullying, and different types of bullying. These subtopics can each go in a bubble that branches off from the main bubble, like this:

Then, keep branching off of these bubbles with additional ideas, categories, subcategories—anything you can think of that’s related, including words, phrases, facts, quotations, questions, examples, and sources. Pretty soon, your mind map will start looking like this:

As your mind map grows, use arrows to connect your ideas. You might first think about sharing photos as a type of bullying done through text messaging, for example, but then realize that bullying through Facebook can also involve sharing photos. Even though the “Sharing photos” bubble branches off of the “Texting” bubble, you can link “Facebook/social networks” to “Sharing photos” with an arrow.

Creating a mind map can be a freeing way to capture and connect all of your ideas on a topic. Even if you’re more comfortable with a traditional outline, you might find—as I did—that using a different form of brainstorming and note-taking can help expand your thinking and see connections you might have otherwise missed. Also, looking at the overall structure of your mind map can help you determine if you need to broaden or narrow your topic to match the scope of your assignment.

Next time you need to choose a paper topic, take notes, or beat a writer’s block, try this exercise:

- Get out a piece of paper or sign up for Bubbl.us (you can save up to three mind maps with a free account).

- Put your main idea in a bubble at the center of the page or space.

- Spend 10 minutes building your mind map, creating additional bubbles and sub-bubbles that branch off of your main idea.

- Pause, and look at your whole map. Draw lines or arrows to connect related ideas.

Here are a couple tips to keep in mind:

- Use words and phrases, rather than full sentences, in your bubbles.

- Don’t worry about your map looking professional—it’s okay to go a little wild, and it’s okay if no one else understands how to read your map. Your map only needs to make sense to you.

- Don’t limit yourself! The more bubbles, the better. Getting your ideas down on paper (or a screen) can spark others. Afterward, you can always delete bubbles that do not belong.

Mind mapping is not just for academic writing. It can be a helpful tool in the workplace, too. The Wall Street Journal recently published an article on how one financial advisory firm is using mind mapping to help clients negotiate financial planning.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A former teacher of college composition courses, Writing Instructor Anne Shiell is a self-described punctuation geek.

Punish the Procrastinator! A Review of the Write or Die App

By Kayla Skarbakka and Nik Nadeau, Writing Consultants

You have a looming deadline and are just about to start that paper when you notice the dust bunnies under your desk. A text from your daughter. That new episode of Parks and Recreation on Hulu.

Sound familiar? Oftentimes, “sitting down to write” means “doing everything I can think of to avoid writing.” If you—like many of us in the Writing Center—find yourself in that situation a bit too frequently, you might want to check out Write or Die, a free online application (also available for purchase on iPad or Desktop) that helps writers combat procrastination.

According to Write or Die’s creator, the so-called “Dr. Wicked,” the app uses negative reinforcement to get writers to put words on the page. Using the app is simple: set yourself a time and word goal and get to work. As long as you keep typing into the text box, you are in the clear.

Think twice, though, before pausing to read that new e-mail or grab another cup of coffee. If you stop typing for more than a few seconds, you face consequences ranging from a gentle pop-up reminder to keep writing (Gentle Mode) to an unpleasant sound that persists until you continue typing (Normal Mode) to self-erasing text (Kamikaze Mode). The final consequence level, “Electric Shock Mode,” is, fortunately, not actually a usable option.

In the words of Dr. Wicked, “the idea is to instill in the would-be writer… a fear of not writing” (“Write or Die,” 2013, para. 6), giving writers real and immediate consequences for self-sabotaging behaviors. Intrigued by this idea, writing tutors and professional procrastinators Kayla and Nik decided to try the application to help them with their own writing projects.

Kayla’s Take

After playing around with the various consequence options available in the Write or Die app, I have determined that I am (a) a speedy typer and (b) an awfully slow thinker.

I simply mean that as long as my goal was to get words—any words—on the screen, then the “fear of not writing” was a fantastic motivator. Do I want to hear crying babies, blaring car horns, or “Peanut Butter Jelly Time”? No thank you.

There’s a lot to be said for focusing on quantity. Ten minutes of madcap typing in the Write or Die app (much of it asides like “Oh geez, that’s bad; obviously I will fix that later”), and I managed to work through a plot problem in a story that has been nagging me – no lie – for 2 years.

However, I soon found myself wanting to slow down and write a bit more thoughtfully. I wanted to be picky and playful with language; I wanted to be accurate, deliberate, and detailed. Turns out I can’t write in that way quickly enough for Dr. Wicked, though, and let me tell you: it’s difficult to concentrate with “Never Gonna Give You Up” blasting from your speakers every 15 seconds.

My take on Write or Die: fantastic for brainstorming, generating ideas, and warming up those writing muscles. It might even be helpful for a first draft if you’re battling writer’s block. But once you know what you want to say and are more concerned with how you say it, you might be ready to move to the word processor.

Nik’s Take

Unlike Kayla, my idea of “warming up” for writing is eating, watching YouTube, or finding one more thing to clean with a Lysol wipe. I will do ANYTHING to not write. And I find that the things I do write that I (and sometimes other people) like are those things that I didn’t really care about. Now let me explain: I care about my writing. Deeply.

But what I really need more than to care about my writing is to NOT care. To further explain, let me give an illustration:

So as you can see, where Kayla would prefer to avoid getting her ears blasted by crying babies, car horns, and every possible song that should never have been introduced to human culture, I WELCOME it. I need to be shoved off a cliff to write consistently. And, well, if that’s the way it is, I’d rather listen to “Never Gonna Give You Up” over and over again rather than, you know, actually getting shoved off a cliff.

Editor's note: Other writing apps that aim to minimize distraction are Flowstate, Freedom, and WriteRoom. Let us know what you think of these apps. Do they work for you?

General Guidance on Data Displays

By Tim McIndoo, Dissertation Editor

According to APA style, a table has a row–column structure; everything else is called a figure (chart, map, graph, photograph, or drawing). This post won't discuss the creation of a figure—the possibilities are endless—except to say that figures are not enclosed in a box (as they are in the APA Publication Manual). If you’ve not created a table before, it may take a little practice.

Here’s guidance on the (a) keyboard steps to create a table, (b) the opposite formatting of tables and figures, and (c) the APA and Walden requirements.

A. Keyboard steps to create a table

In the Word toolbar, go to Table > Insert > Table > Table size. Pick the number of columns and rows you think you’ll need. Make sure to add one each for the headers of the table and the stub column (which lists the individual items).

Under AutoFit behavior, try AutoFit to Contents. That way, your table will automatically expand to fit whatever data you put in the various cells. You can always change it later.

Under Table Style, try Table Normal. It’s standard, it’s simple, it’s clean.

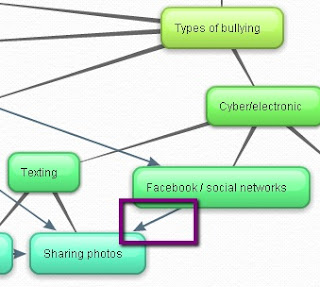

B. Formatting tables and figures (and the three forms of notes used at the end of a table). Note how tables and figures are formatted in opposite ways.

C. APA and Walden requirements

- All cells in a table, and callouts in a figure, use sentence case.

- APA style does not use boldface type or vertical lines in tables.

- Do not put a box around a figure.

- Make titles and captions concise, clear, and expressive. (APA 5.12 & 5.23)

- Do not split a table unless it is too large to fit on one entire page. It works best to start tables at the top of a page; that way, there will generally be enough space. It’s OK if the table appears on the page following its first mention.

- If a table is, indeed, too large for one page, then type (table continues) under the table, flush right. Repeat the column headings (not the table title) at the top of the new page.

- If a table or figure takes up 75% or more of a page, then set no text on that page.

- If needed, use a different point size (or font) for the text of the table or figure, but in any event, do not use smaller than 8-point type.

- For numerous examples of tables, see APA Publication Manual, pp. 129–150; for numerous examples of figures, see pp. 152–166. I would encourage studying them all closely. You can also see several examples on the Writing Center website.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Tim McIndoo, who has been a dissertation editor since 2007, has more than 30 years of editorial experience in the fields of medicine, science and technology, fiction, and education. When it comes to APA style, he says, "I don't write the rules; I just help users follow them."

There’s an App for That: Top 5 Writing Apps for 2013

By Julia Cox, Writing Consultant

Do you ever wish an omnipotent force would freeze your browser and lure you back to your writing project?

Not to be cliché, but there’s an app for that. Technology has made it easier than ever to manage your time, enhance your writing, and achieve your academic goals. As I sit here attempting to write this blog post on a sleepy Sunday—with open tabs of Facebook, Perez Hilton, Oprah.com, and Gchat—I can certainly relate.

In no particular order, here are some popular apps to help you make the best of your writing:

Freedom literally takes away your ability to browse the web during certain hours. Simply load the software, tell the program how long you wish to write internet free, and it does the rest. Highly recommended for procrastinators, blog junkies, and professional time wasters. If the antics of Justin Bieber hinder your writing goals, this app’s for you.

Adhering to the mantra of no bad crash goes unpunished, Dropbox prevents a computer disaster from signaling a lost document. Available for computers and mobile devices, Dropbox saves all files to a cloud folder accessible anywhere.

Grammar App HD

This app contains four sections—Learn, Test, Games, and Progress—helping users master trickier grammar topics. You can also use Grammar App as a guidebook for common rules and guidelines.

Dragon Dictation

Ever had a brainwave on the go? Needed to jot down a personal communication? This iPhone/iPad app is a transcriber for the future. Simply speak into the app and it generates text. You can then email it to yourself or store it on the app. You can even tell Dragon Dictation to send texts!

Advanced English Dictionary and Thesaurus

This is not your average mobile dictionary. With 250,000 entries, 1.6 million words, and 134,000 pronunciation guides, the AED can help you determine the right word, access synonyms, discover root words, compare multiple meanings, and find examples. It’s also excellent Scrabble training.

Have a favorite writing app not on this list? Feel free to Tweet or Facebook our pages and tell us about it!Presenting With Prezi

By Anne Torkelson, Writing Consultant

One of the most impressive presentations I’ve ever seen involved a PowerPoint with only one image per slide, and often no text. The presenter chose one visually stimulating photograph to represent each main point, and he let his message rather than his slides drive the presentation. No one in that audience fell asleep.

The presentation was successful because it combined image and discussion in an effective way, but also because the new approach—so different than the “death by PowerPoint” we are often subjected to—caught and kept the audience’s attention.

Many Walden students use PowerPoint, and use it well, for class projects and work presentations. Trying a new style or approach can sometimes bring new life and new ideas to your work, however. For today’s Tech Tip, I’d like to introduce you to a tool for jazzing up your presentations: Prezi.

D-O-I & Y-O-U

By Tim McIndoo, Dissertation Editor

A reference tells us who wrote what–when–where (author, year, title of article, journal, volume, issue, page range). If we take those data to a large scholarly library and attack the journal stacks, chances are good we’ll find it. But how slow and cumbersome!

In the 21st century, filing and retrieving scholarly articles (including abstracts) has become much simpler and much faster. That’s because all the standard data (author, year, title, etc.) are now commonly encoded into a unique, permanent, alphanumeric string called a digital object identifier or DOI. Here’s what a reference looks like with the DOI in position after the period that follows the page range:

Nance, M. A. (2007). Comprehensive care in Huntington’s disease: A physician's perspective. Brain Research Bulletin, 72(2-3), 175-178. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.10.027

To AutoRecovery, With Love

By Julia Cox, Writing Consultant

On August 21, 2009, tragedy struck. My MacBook crashed, exactly 11 hours before I was to begin a fresh term of graduate classes.

The next day, I stood petrified in the Apple Store, ready to pen a “dear Steve” letter (to late Apple founder Steve Jobs) bemoaning that my overpriced, allegedly immortal MacBook had come undone, my personal history interrupted, my Alexandria burned.

Indeed, the digital age has conjured new forms of personal crisis, where a frayed motherboard wire can extinguish vacation memories, silence a music collection, and destroy a canon of professional and academic documents in the space of a few seconds.

For students, technological catastrophe can be especially traumatizing, as it always strikes with an impending deadline. Microsoft users will recognize the blue screen of death. For Mac patrons like me, disaster starts with the rainbow wheel of pain. Regardless of which team you click for, the feeling of loss, pain, and nausea is the same.

AutoCorrect: The New Shorthand

If you want to speed up your work and improve the accuracy of your typing, you might try using Word’s AutoCorrect feature. It can store and paste up to 255 characters.

To access this function,

Using AutoCorrect in Word 2007

To access this function,

1. Click on the Office button in the upper left corner of the screen. A screen pops up.

2. Click on Word Options at the bottom right.

3. From the menu bar on the left, click on Proofing (third option from the top). Then look for the first heading on the page and click on the box labeled "AutoCorrect Options." The AutoCorrect dialog box then appears. Here is a screen shot of the AutoCorrect dialog box, ready for entry of a new item:

2. Click on Word Options at the bottom right.

3. From the menu bar on the left, click on Proofing (third option from the top). Then look for the first heading on the page and click on the box labeled "AutoCorrect Options." The AutoCorrect dialog box then appears. Here is a screen shot of the AutoCorrect dialog box, ready for entry of a new item:

Subscribe to: Posts ( Atom )

.png)