Are Today's Youth Really a Lost Generation?

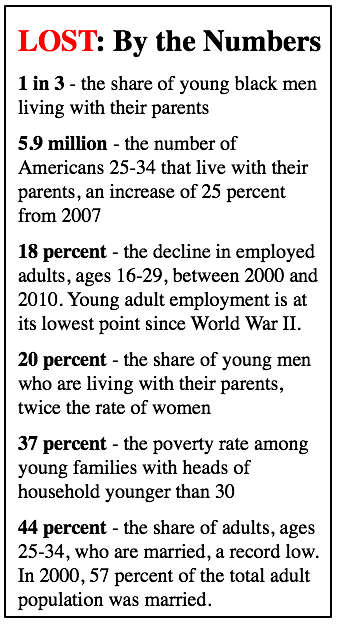

They're calling us the "Lost Generation." Young people are struggling in record numbers to find work, leave home, and start a family, according to 2010 Census figures released today.

The proximate cause is the Great Recession. The number of young Americans living with their parents, nearly 6 million, has increased by 25 percent in the last three years. But the greatest cause for concern is that even when the recession has finally let go of the economy, young Americans -- Generation Y or Millennials -- will face a longer road back to normalcy than their older peers and parents.

Last week, I compared the impact of the recession on three generations: Gen-Y, Gen-X, and Boomers. Each face a particular challenge. For Boomers, it's a wealth crisis. They invested in homes whose value has fallen by as much as 30 percent. For Gen-X, it's an income crisis. They should be in the highest-earnings years of their life, but the recession has depressed their salaries and threatened their pensions. For Gen-Y, it's about the future. The money they're not making today is a problem. But the money they might not make tomorrow is a greater concern. Two decades after graduating into a recession, an unlucky generation can continue earning 10 percent less than somebody who left school a few years before or after the downturn. When Don Peck added it all up, he found "it's as if the lucky graduates had been given a gift of about $100,000, adjusted for inflation, immediately upon graduation."

For Millennials, this is the great irony of the Great Recession. A crisis that started in the housing market could wind up having the most lasting negative impact on the one generation that didn't own any homes before the bust.

We're living within two crises. The Great Recession and the greater recession. The Great Recession is a demand crisis. The wealth shock of 2008 devastated the housing market, reduced demand for goods and services, and slowed the growth of spending and income. As latent demand reemerges -- naturally, over a long period of time, or pulled forward with stimulus -- the Great Recession will end.

But the greater recession will not. Men with low education attainment will continue to see their real incomes fall. Americans looking for work in manufacturing, IT and media will continue to find their positions under assault. In this greater recession, we are in a race between education and the twin forces of technology and globalization. It's hard to say how this trend would continue to play out for families. Would more women bypass marriages as they outearn their male peers? Or 30-somethings return to dual-earner households in the face of declining earnings in the middle class? I'm not a prophet. But it seems to me that these socio-cultural questions will come down to this tango between education attainment that enhances skills and earnings and corporate productivity that finds a way around U.S. jobs.

The news here is not all bad. The Census reports that there were "significant increases in educational attainment between 2009 and 2010." The percent of people of 25 with high school degrees increased to 85.6 percent, and the percent with bachelor's degrees increased to 28.2. College graduates have never been more numerous in the U.S. (despite what you might have heard) and the benefit of college has never been more clear (despite what you might have heard). It's lamentably boring to conclude a column about poverty and income with a "stay in school" mantra, but -- spoiler alert -- that's exactly how this column is about to end.

Investments are notoriously risky. If stock markets were safe, there would be no crashes. If bonds were safe, there would be no defaults. If mortgages were safe, there would be no Great Recession. But stocks do crash, bonds can default, and home values can fall. The safest and most profitable bet we know is a college education.

"The $102,000 investment in a four-year college yields a rate of return of 15.2 percent per year," the Hamilton Foundation reported, "more than double the average return over the last 60 years experienced in the stock market" and more than five times the return in corporate bonds, gold, long-term government bonds, or housing.

Whether or not this is a "lost generation" depends first on our recovery from the Great Recession. But in the decades after, it will depend on our ability to attain skills that match with the needs of consumers and employers through undergraduate degrees, retraining programs, and online education. More on that story in our special project next week on college and college applications. Stay tuned.