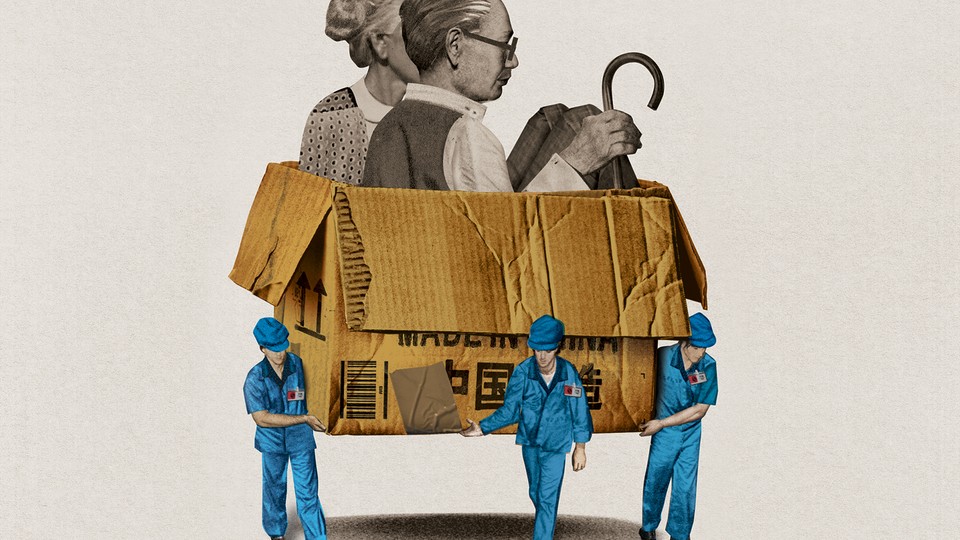

China’s Twilight Years

The country’s population is aging and shrinking. That means big consequences for its economy—and America’s global standing.

On opposite sides of the globe, two debates that will profoundly affect the future of the United States, and indeed the world, are raging. One of them has become shrilly public, while the other remains almost secret. On the surface they might seem to have little to do with each other, but at bottom, they are inextricably linked.

The first debate, which is unfolding in America, concerns immigration. Republicans like Donald Trump and Ted Cruz have staked out some of the more radical positions in this debate, such as urging that the U.S. build a wall to keep out illegal immigrants and that it deport the millions who are already here. The other debate, which is playing out in Beijing, is about how big a navy China should build, and how much it should contest America’s primacy in the world’s oceans.

To a degree scarcely suspected by most people, both debates—and more generally, America’s chances of maintaining its standing in the world—are bound up in the two countries’ sharply contrasting population dynamics.

Under President Xi Jinping, China has until very recently appeared to be a global juggernaut—hugely expanding its economic and political relations with Africa; building artificial islands in the South China Sea, an immense body of water that it now proclaims almost entirely its own; launching the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, with ambitions to rival the World Bank. The new bank is expected to support a Chinese initiative called One Belt, One Road, a collection of rail, road, and port projects designed to lash China to the rest of Asia and even Europe. Projects like these aim not only to boost China’s already formidable commercial power but also to restore the global centrality that Chinese consider their birthright.

As if this were not enough to worry the U.S., China has also showed interest in moving into America’s backyard. Easily the most dramatic symbol of this appetite is a Chinese billionaire’s plan to build across Nicaragua a canal that would dwarf the American-built Panama Canal. But this project is stalled, an apparent victim of recent stock-market crashes in China.

Many economists believe that these market plunges are early manifestations of a historic slowdown in the Chinese economy, one that is bringing the country’s soaring growth rates down to earth after three decades of expansion. But the current slowdown pales in comparison with a looming societal crisis: In the years ahead, as China’s Baby Boomers reach retirement age, the country will transition from having a relatively youthful population, and an abundant workforce, to a population with far fewer people in their productive prime.

The frightening scope of this decline is best expressed in numbers. China today boasts roughly five workers for every retiree. By 2040, this highly desirable ratio will have collapsed to about 1.6 to 1. From the start of this century to its midway point, the median age in China will go from under 30 to about 46, making China one of the older societies in the world. At the same time, the number of Chinese older than 65 is expected to rise from roughly 100 million in 2005 to more than 329 million in 2050—more than the combined populations of Germany, Japan, France, and Britain.

The consequences for China’s finances are profound. With more people now exiting the workforce than entering it, many Chinese economists say that demographics are already becoming a drag on growth. More immediately alarming are the fiscal costs of having far more elderly people and far fewer young people, starting with the expense of creating the country’s first modern national pension system.

Unlike residents of China’s prosperous eastern cities, hundreds of millions of peasants and migrant laborers have scant personal savings and rudimentary retirement coverage, if any. “One goal is to extend pension coverage to everyone,” says an economist with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in Beijing. “But that will be very expensive, because most people haven’t paid anything into the system at all. Basically, what this means is a wealth transfer.” Providing health care to these same disadvantaged classes will also be vastly expensive.

Mark L. Haas, a Duquesne University political scientist, has for some time warned of a looming contest between guns and canes—a variant on the old idea of guns versus butter—as the world’s major countries grapple with demographic change. “China’s political leaders beginning in roughly 2020 will be faced with a difficult choice: allow growing levels of poverty within an exploding elderly population, or provide the resources necessary to avoid this situation,” Haas writes in Political Demography. If China’s government decides in favor of the latter option, Haas argues, American power will benefit. More broadly, he foresees a coming “geriatric peace,” as nations around the world find themselves too burdened to challenge America’s military preeminence.

Recent events may well provide a preview of this reality. When Xi Jinping announced last year that he was slashing China’s armed forces by 300,000 troops, Beijing spun the news as proof of China’s peaceful intentions. Demographics provide a more compelling explanation. With the number of working-age Chinese men already declining—China’s working-age population shrank by 4.87 million people last year—labor is in short supply. As wages go up, maintaining the world’s largest standing army is becoming prohibitively expensive. Nor is the situation likely to improve: After wages, rising pension costs are the second-biggest cause of increased military spending.

Awakening belatedly to its demographic emergency, China has relaxed its one-child policy, allowing parents to have two children. Demographers expect this reform to make little difference, though. In China, as around the world, various forces, including increasing wages and rising female workforce participation, have, over several decades, left women disinclined to have large families. Indeed, China’s fertility rate began declining well before the coercive one-child restrictions were introduced in 1978. By hastening and amplifying the effects of this decline, the one-child policy is likely to go down as one of history’s great blunders. Single-child households are now the norm in China, and few parents, particularly in urban areas, believe they can afford a second child. Moreover, many men won’t become fathers at all: Under the one-child policy, a preference for sons led to widespread abortion of female fetuses. As a result, by 2020, China is projected to have 30 million more bachelors than single women of similar age.

“It really doesn’t matter what happens now with the fertility rate,” a demographer at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences told me. “The old people of tomorrow are already here.” She predicted that in another decade or two, the social and fiscal pressures created by aging in China will force what many Chinese find inconceivable for the world’s most populous nation: a mounting need to attract immigrants. “When China is old, though, all the countries we could import workers from will also be old,” she said. “Where are we to get them from? Africa would be the only place, and I can’t imagine that.”

Not so long ago, conventional wisdom in China held that the country’s economy would soon overtake America’s in size, achieving a GDP perhaps double or triple that of the U.S. later this century. As demographic reality sets in, however, some Chinese experts now say that the country’s economic output may never match that of the U.S.

With American Baby Boomers entering retirement, the United States has its own pressing social-safety-net costs. What is often neglected in debates about swelling entitlement spending, however, is how much better America’s position is than other countries’. Once again, numbers tell the story best: By the end of the century, China’s population is projected to dip below 1 billion for the first time since 1980. At the same time, America’s population is expected to hit 450 million. Which is to say, China’s population will go from roughly four and a half times as large as America’s to scarcely more than twice its size.

Even as China’s workforce shrinks, America’s is expected to increase by 31 percent from 2010 to 2050. This growing labor supply will boost economic growth, strengthen the tax base, and relieve pressure on the Social Security system. At the same time, Americans will continue to enjoy a substantial advantage over the Chinese in terms of per capita income. This advantage in wealth will continue to underwrite U.S. security commitments and capabilities around the world.

That the U.S. is not facing population shrinkage is due largely to immigration. America’s fertility rate, while higher than that of China and many European countries, is still below the threshold required to avoid shrinkage, about 2.1 children per woman. By keeping its doors relatively open to newcomers, America is able to replenish itself. If the country were instead to shut its doors, its population would plateau and its median age would climb more steeply. According to the Pew Research Center, immigrants and their children and grandchildren will account for 88 percent of U.S. population growth over the next 50 years.

These new arrivals are widely portrayed in a variety of ways that fail to convey their true importance to the American economy and future. Sometimes they are thought of as undesirables who get by doing scut work. Other times they are depicted as taking good jobs and opportunities from citizens. In some cases, they are demonized as criminals. Less often, they are romanticized as the brainpower driving American technological ingenuity.

The truth is broader and far less exotic. America assimilates outsiders on a scale matched by no other powerful country: Immigrants inhabit every rung of society and work in every sector. Immigration, perhaps more than any other single factor, sustains American prosperity. And immigration will, shrieking campaign rhetoric notwithstanding, spare the United States the fate now threatening to engulf its competitors.