Abstract

Background:

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) growth relies on angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) release. Hypoxia within tumour environment leads to intracellular stabilisation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (Hif1α) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT3). Melatonin induces apoptosis in HCC, and shows anti-angiogenic features in several tumours. In this study, we used human HepG2 liver cancer cells as an in vitro model to investigate the anti-angiogenic effects of melatonin.

Methods:

HepG2 cells were treated with melatonin under normoxic or CoCl2-induced hypoxia. Gene expression was analysed by RT–qPCR and western blot. Melatonin-induced anti-angiogenic activity was confirmed by in vivo human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) tube formation assay. Secreted VEGF was measured by ELISA. Immunofluorescence was performed to analyse Hif1α cellular localisation. Physical interaction between Hif1α and its co-activators was analysed by immunoprecipitation and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

Results:

Melatonin at a pharmacological concentration (1 mM) decreases cellular and secreted VEGF levels, and prevents HUVECs tube formation under hypoxia, associated with a reduction in Hif1α protein expression, nuclear localisation, and transcriptional activity. While hypoxia increases phospho-STAT3, Hif1α, and CBP/p300 recruitment as a transcriptional complex within the VEGF promoter, melatonin 1 mM decreases their physical interaction. Melatonin and the selective STAT3 inhibitor Stattic show a synergic effect on Hif1α, STAT3, and VEGF expression.

Conclusion:

Melatonin exerts an anti-angiogenic activity in HepG2 cells by interfering with the transcriptional activation of VEGF, via Hif1α and STAT3. Our results provide evidence to consider this indole as a powerful anti-angiogenic agent for HCC treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Over half a million new cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are diagnosed each year, being the main malignant hepatobiliary disease and the third cause of cancer-related death worldwide (Jemal et al, 2011). Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with cirrhosis and hepatic dysfunction in 80% of patients, which makes its prognosis and treatment more difficult than in many other cancers (Sengupta and Siddiqi, 2012). Dysregulation of cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis is frequently associated with HCC development and progression, and understanding these molecular pathways becomes essential to the development of effective therapies (Cornella et al, 2011). Like some other solid tumours, HCC growth relies on new vessels formation, required for nutrients and oxygen supply (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Incipient success of anti-angiogenic therapy in similar tumours (Hurwitz et al, 2004; Johnson et al, 2004) suggests that adjuvant anti-angiogenic agents combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy may be particularly attractive approaches to target tumour and endothelial cells, and thus, to enhance treatment efficacy (Sun and Tang, 2004).

Deficit of oxygen availability within the tumour microenvironment is highly associated with tumour progression (Albini et al, 2012). Oxygen homeostasis is directly regulated via hypoxia inducible factor 1 (Hif1α). Whereas normoxia leads to its ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation, under hypoxia, Hif1α is stabilised and able to translocate to the nucleus, where it induces the expression of several genes such as erythropoietin (EPO), nitric oxide synthases, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Vaupel, 2004). Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted protein that acts as a potent mitogen for vascular endothelial cells and some other cell types, being one of the main regulatory factors in angiogenesis and neovascularisation (Ferrara et al, 2003). Moreover, VEGF appears frequently hyperexpressed in HCC tissues, which consistently correlates with tumour size and histologic tumour grade (Tischer et al, 1991). Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a well-known oncogene in HCC and in some other tumour types (Ji and Wang, 2012). Besides its participation in normal physiological processes, it has been found constitutively activated in cancers, transcriptionally activating oncogenes encoding for apoptosis inhibitors and cell-cycle regulators, such as Bcl-x(L), cyclin D1, and c-Myc (Wang et al, 2012). Many studies suggest that, like Hif1α, STAT3 also behaves as an angiogenesis inductor involved in VEGF expression; activated via phosphorylation, it enhances Hif1α stability and acts as a co-activator under hypoxia (Jung et al, 2005). Interestingly, both STAT3 and Hif1α have been associated in mediating VEGF transcription, and the presence of regulatory sites located in high proximity within its promoter suggests their close cooperation in the transcriptional regulation of this growth factor (Niu et al, 2008).

Nowadays melatonin, the main product of the pineal gland, has attracted increasing attention because of its protective role in several pathophysiological situations, including different cancer types, where it exerts oncostatic effects (Hill and Blask, 1988; Farriol et al, 2000; Futagami et al, 2001; Cini et al, 2005; Garcia-Santos et al, 2006; Garcia-Navarro et al, 2007; Mauriz et al, 2007; Cabrera et al, 2010; Chiu et al, 2010; Gonzalez et al, 2010; Carbajo-Pescador et al, 2011, 2013). Our group has shown the melatonin oncostatic activity in HepG2 liver tumour cells, highlighting its pro-apoptotic properties through upregulation of cell death-related processes (Martin-Renedo et al, 2008; Carbajo-Pescador et al, 2009, 2011, 2013). In addition, it has been recently reported a mechanism by which melatonin sensitises human hepatoma cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces apoptosis by downregulating COX-2 expression, increasing the levels of CHOP and decreasing the Bcl-2/Bax ratio (Zha et al, 2012). Melatonin anti-angiogenic properties have been reported both in in vivo (Cho et al, 2011; Cui et al, 2012) and in vitro models, implementing the existing knowledge regarding to its oncostatic role (Kim et al, 2013). Moreover, a significant decline in the serum levels of VEGF has been found in metastatic cancer patients with different histotypes, including HCC, when treated with melatonin, which suggests that its ability to control tumour growth could be related, at least in part, to its anti-angiogenic features (Lissoni et al, 2001). However, the precise mechanism that underlies melatonin anti-angiogenic effects in HCC has not been fully elucidated. Herein, the present research was aimed to assess melatonin action on tumour angiogenesis in an in vitro model of HCC, focusing on its ability to interfere with the transcriptional activation of VEGF via Hif1 and STAT3.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Stock cells routinely were grown as monolayer cultures in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1), glutamine (4 mM), and pyruvate (100 μg ml−1) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C and the medium was changed every other day. Cell culture reagents were from Gibco (Life Technologies, Madrid, Spain). Melatonin was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Confluent HepG2 cells growing in complete media were replated in 9.6 cm2 culture dishes, at a density of 150 000 cells/plate, in 2 ml of complete medium. After 24 h, the plating medium was replaced with fresh medium containing melatonin dissolved in DMSO (0.2% DMSO final concentration in the plate). Two melatonin concentrations were tested, 1 nM (within the 0.3–1.2 nM physiological range), and 1 mM as a supraphysiological/pharmacological concentration (Cui et al, 2012). CoCl2 was added at a final concentration of 100 μ M to mimic hypoxia. Among all the divalent metals that act as hypoxic mimetics, CoCl2 has shown to induce hypoxia, increasing Hif1α stability by antagonising Fe+2, an essential cofactor required for oxygen to interact with prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) and degradate Hif1α (Bansal, 2009). Besides, our dose of cobalt has been previously used to induce hypoxia with non-toxic effects (Dai et al, 2008). For inhibition studies, hepatocytes were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 μ M Stattic (Tocris, Bristol, UK) for 1 h before treatment.

Western blot analysis

After treatments, cultured cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed by adding ice-cold RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% sodium deoxycholate, 10% SDS, 1 mM NaF and protease cocktail inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and scraped off the plate. The extract was transferred to a microfuge tube and centrifuged for 10 min at 15 000 g. Equal amounts of the supernatant protein (20 μg) were separately subjected to SDS–PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C with polyclonal antibody to VEGF (rabbit, 1 : 1000 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Hif1α (rabbit, 1 : 1000 dilution; Abcam), Phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) (D3A7) from mouse and Stat3 from rabbit 1 : 100 dilution (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Equal loading of protein was demonstrated by probing the membranes with a rabbit anti β-actin polyclonal antibody (1 : 2000 dilution; Sigma). After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (1 : 4000; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and visualised using ECL detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). The density of the specific bands was quantified with an imaging densitometer (Scion Image, Maryland, MA, USA).

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR

For real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT–PCR), confluent HepG2 cells growing in complete media were replated in 6-well culture plate, at a density of 150 000 cell/well in a total volume of 2 ml of complete medium. After treatment, total RNA was obtained by using a Trizol reagent (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and quantified by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop 1000; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Residual genomic DNA was removed by incubating RNA with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesised using M-MLV RT (Roche Molecular Systems), and the negative control (no transcriptase control) was performed in parallel. cDNA was amplified using FastSt art TaqMan Probe Master (Roche) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan primers and probes for Hif1α (NM_001530 and Hs00153153_m1) and VEGF (NM_001025366 and Hs00900055_m1) genes were derived from the commercially available TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems). Relative changes in gene expression levels were determined using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Crespo et al, 2008). The cycle number at which the transcripts were detectable (CT) was normalised to the cycle number of β-actin detection.

Tube formation assay

Basement membrane extracellular matrix (Matrigel, BME, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) was thawed at 4 °C overnight. A 96-well plate and 200 μl pipette tips were also kept at 4 °C overnight and both the plate and tips were placed on ice during the entire experiment. In all, 50 μl of Matrigel was loaded in each well of the 96-well plate and the plate was incubated at 37 °C in a tissue culture incubator for 30 min to allow the matrix to polymerise. Trypsinised human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) from a primary culture with rare or non expression of endogenous VEGF were mixed with EBM-2 supplemented with VEGF (20 ng ml−1) or the conditioned media (CM) from HepG2 cells incubated under hypoxia (CoCl2) with or without the pharmacologic concentration (1 mM) of melatonin for 24 h, making the appropriate cell density (25 000 cells/well) and added on top of the gel in the 96-well plate. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C in a tissue culture incubator and the formation of the capillary-like tubes was observed after 6 h. Wells were imaged using a Nikon microscope. Quantification of tube formation was assisted by S.CORE, a web-based image analysis system (S.CO BioLifescience, Munich, Germany). Tube formation indices represent the degree of tube formation. The indices were calculated using the following equation: (tube formation index)=(mean single tube index)2 × (1−confluent area) × (number of branching points/total length skeleton). The values of the variables used in the equation were obtained automatically by S.CORE.

Quantitation of VEGF production

Media were collected from 200 000 cells in 6-well culture plates and centrifuged at 800 r.p.m. for 4 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris and then stored at 70 °C. Vascular endothelial growth factor in the medium was measured by using the Quantikine human VEGF ELISA kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to manufacturer’s instruction.

Hif1α transcription activity assay

The Hif1α transcriptional activity was analysed by Hif1α transcription factor assay using TransAM HIF-1 transcription factor assay kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, nuclear extracts were added onto 96-well microplate coated with oligonucleotides containing hypoxia response element (HRE) (5′-TACGTGCT-3′) from the EPO gene. The HIF dimers present in nuclear extracts bind with high specificity to this response element and are subsequently detected with an antibody directed against Hif1α. Addition of a secondary antibody conjugated to HRP provides a sensitive colorimetric readout that is easily quantified by spectrophotometry. The HeLa-CoCl2 nuclear extracts provided with the commercial kit were used as a positive control of Hif1α transcriptional activity. Values are expressed as optical density (OD) at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 655 nm.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HepG2 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and EDTA-Free Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) for 30 min on ice. Total cell lysates (1 mg of protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with 2 μg of anti-phospho0STAT3 (Santa Cruz), anti-Hif1α (Abcam), and anti-Acetyl-CBP (Lys1535)/p300 (Lys1499) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) for 1 h at 4 °C. Protein G Sepharose (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) was added and incubation continued overnight at 4 °C. Precipitates were washed three times with ice-cold lysis buffer, resuspended in Laemmli buffer, and boiled for 10 min. Bound proteins were separated on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel and analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

ChIP assay

Chromatin of cultured cells was fixed and immunoprecipitated according to Benet et al (2010). Cells were incubated with 100 μ M CoCl2, 1 mM melatonin and both together for 24-h period. Then, cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde in PBS buffer by gentle agitation for 10 min at room temperature to crosslink proteins to DNA. Next, cells were washed, resuspended in lysis buffer and sonicated on ice for 8 × 15 s steps at a 20% output in a Branson Sonicator. Sonicated samples were centrifuged to clear supernatants. DNA content was quantified by picogreen (Life Technologies) and properly diluted to maintain an equivalent amount of DNA in all the samples (input DNA). For the immunoprecipitation of protein–DNA complexes, 4 μg of specific antibody (anti-HIF1α NB100-134; NOVUS Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) and rabbit pre-immune IgG (sc-2027, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) (background DNA fraction) were added. Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C on a 360° rotator (antibody-bound DNA fraction). Immunocomplexes were affinity absorbed with 60 μl of protein G agarose/Salmon Sperm DNA (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) (pre-washed with lysis buffer for 1 h at 4 °C by gentle rotation), and collected by centrifugation (1000 r.p.m., 1 min). The antibody-bound and background DNA fractions were washed as described in Benet et al (2010). Crosslinks were reversed by adding 100 μl of 10% Chelex (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and boiling for 10 min. The Chelex/protein G bead suspensions were incubated with proteinase K (20 mg ml−1) for 30 min at 55 °C while shaking, followed by another 10 min boiling. Suspensions were centrifuged and supernatants were collected. The eluates were used directly (input 1/5) as a template for Q-PCR with a LightCycler 480 instrument. Amplification was real-time monitored, stopped in the exponential phase of amplification and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Amplifications of the VEGF gene sequences among the pull of DNA were performed with specific primers flanking from −1041 to −750 region, forward 5′-CAGGAACAAGGGCCTCTGTCT-3′, reverse 5′-TGTCCCTCTGACAATGTGCCATC-3′. The PCR conditions for the VEGF promoter region were 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, 1 min at 72 °C. The amplification of the VEGF promoter region was analysed after 35 cycles.

Immunofluorescence analysis

To study the localisation of Hif1α, staining of Hif1α was performed on HepG2 cells. Cells were grown on coverslips for 24 h. Thereafter, cells were treated with melatonin as indicated. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilised with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, and pre-treated with blocking solution. After fixation and after blocking the non-specific binding, the coverslips were incubated with rabbit anti Hif1α (HIF1α NB100-134, NOVUS Biologicals) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Thereafter, the secondary antibodies donkey anti-rabbit conjugated with FITC (Jackson Immuno Research, Baltimore, PA, USA). After washing, the coverslips were mounted on DakoCytomation Fluorescent Mounting Medium (DAKO). The preparations were analysed with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Melville, NY, USA). Image analysis was performed using the ImageJ software v3.91 (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). To quantify Hif1α nuclear translocation, results from fluorescence colocalisation studies were represented graphically in scatterplots where the intensity of one colour was plotted against the intensity of the second colour for each pixel. Nuclear regions were defined as ‘region of interest’ (ROI) to determine Hif1α nuclear translocation, and the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) was used as a statistic for quantifying colocalisation.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean values±s.e.m. of the indicated number of experiments. A t-test was used to determinate differences between pairs of treatments, as indicate in results. One-way ANOVA followed by Student–Newmann–Keuls post hoc test was used to determine differences between the mean values of the different treated groups. P<0.05 was considered as significant. Values were analysed using the statistical package Statistica 10.0 (Statsoft Inc, Tulsa OK, USA).

Results

Effect of melatonin on VEGF levels and hypoxia-induced angiogenesis

Oxygen deficiency is a hallmark of solid tumours that drives VEGF production and angiogenesis. To determine the effect of oxygen levels on angiogenesis-related factors in our in vitro model of HCC, HepG2 cells were incubated in normoxia or exposed to CoCl2 (100 μ M) as a hypoxia mimetic in a kinetic experiment from 2 to 24 h.

As shown in Figure 1A, there was a hypoxia-dependent VEGF induction from the first 2 h of treatment, and an increase in the protein levels of Hif1α and phospho-STAT3 which reached a maximum at 24 h, time at which the inhibitory effect of the pharmacological melatonin concentration (1 mM) resulted more effective. Once our experimental conditions were set up and the use of CoCl2 as an effective hypoxia inductor confirmed, the 24-h time point was chosen for further experiments.

Effect of melatonin on VEGF levels and hypoxia-induced angiogenesis. HepG2 cells were incubated in normoxia or exposed to CoCl2 (100 μ M) as a hypoxia mimetic in a kinetic experiment from 2 to 24 h, and VEGF, Hif1α phospho-STAT3, and STAT3 protein expression was analysed by western blot (A). Effect of normoxia/hypoxia and melatonin treatments on VEGF mRNA levels (B), VEGF cell protein levels (C) and VEGF secreted to the culture media (D). HUVECs tube formation assay (E). Tube formation index (S.CORE) (F). Data are expressed as a percentage of mean values±s.e.m. of four experiments performed in triplicate. *p<0.05 significant differences vs control. #P<0.05 significant differences between CoCl2 and melatonin+CoCl2-treated cells.

Beside growth factors and interleukins, hypoxia is the major VEGF inductor, which stimulates new capillary vessels formation to counteract low oxygen tension. Thus, in our experiments, 24 h of 100 μ M CoCl2 treatment effectively enhanced VEGF mRNA levels (Figure 1B). Significant increases in VEGF protein expression and in the amount of VEGF released into the culture medium were also observed (Figures 1C and D). Moreover, as shown in Figure 1, melatonin did not exert a significant effect on protein levels in normoxia, only affecting the amount of secreted VEGF under these conditions. By contrast, melatonin treatment did clearly reduce hypoxia-induced VEGF expression and release to the medium.

To further confirm melatonin anti-angiogenic activity suggested by the induced decrease of VEGF levels under hypoxia, HUVECs tube formation assay was performed. HepG2 cells were cultured under conditions of CoCl2-induced hypoxia with or without the pharmacological concentration of melatonin (1 mM) for 24 h, and CM were applied to HUVECs in a series of angiogenic assays. As show in Figure 1E, hypoxia induced HUVECs to display their typical morphology and phenotype of endothelial cells, whereas this effect was prevented by melatonin treatment.

Melatonin inhibits hypoxia-induced Hif1α activation

Once shown that melatonin anti-angiogenic activity is related with its ability to modulate VEGF levels, we next focused on elucidating the molecular mechanisms involved. Assuming that Hif1α is the major regulator of this endothelial growth factor, Hif1α mRNA levels and protein expression were measured in HepG2 cells exposed to normoxia or hypoxia and melatonin treatment. As expected, Hif1α transcription was induced by CoCl2 treatment, as shown by the increases in both mRNA and protein level. Similarly to the effects found on VEGF, only the 1 mM melatonin dose exerted an inhibitory effect on Hif1α-induced expression. However, while Hif1α protein expression was inhibited (Figure 2A), Hif1α mRNA levels did not decrease significantly after melatonin treatment (Figure 2B), even under hypoxia, suggesting that melatonin effects takes place at a post-transcriptional level.

Melatonin inhibits hypoxia-induced Hif1 α activation. Effect of normoxia/hypoxia and melatonin treatments on protein levels (A), Hif1α mRNA levels (B), and Hif1α nuclear translocation (C). Scatterplots of green and blue green pixel intensities and Pearsońs correlation coefficient (PCC) (D). Effect of melatonin treatment on Hif1α transcriptional activity. HeLa cell nuclear extracts treated with CoCl2 provided with the kit were used as a positive control for Hif1α activation (E). Data are expressed as a percentage of mean values±s.e.m. of four experiments performed in triplicate. *p<0.05 significant differences vs control. #P<0.05 significant differences between CoCl2 and melatonin+CoCl2-treated cells.

It is widely accepted that to transcriptionally activate its target genes, Hif1α needs to translocate into the nucleus. Thus, we visualised its dynamic translocation by using fluorescence microscopy of HepG2 untreated or treated cells under normoxia or induced hypoxia. As show in Figure 2C, under normoxia, Hif1α was always located in the cytosol, and melatonin treatment did not affect its location. However, CoCl2 treatment induced Hif1α nuclear translocation, an effect that was prevented by melatonin 1 mM. Furthermore, results were consistent with those observed when measuring Hif1α ability to specifically bind the HRE. As shown in figure 2D, hypoxia significantly enhanced Hif1α transcription, while melatonin inhibited its activation in a dose-dependent manner.

Melatonin prevents hypoxia recruited STAT3/Hif1α/CBP/p300 within VEGF promoter

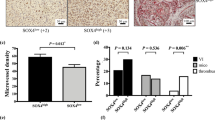

STAT3 is an essential mediator of VEGF transcription by direct binding to its promoter (Niu et al, 2008). Furthermore, it induces Hif1α stability and enhances its transcriptional activity, behaving as a co-activator and conforming a transcriptional complex together with CBP/p300 (Gray et al, 2005). Considering the close relationship between Hif1α and STAT3, we decided to analyse whether effects on Hif1α and VEGF expression could be mediated via STAT3 inhibition. As shown in Figure 2A, CoCl2 treatment resulted in STAT3 activation by phosphorylation at Tyr 705 residue, without affecting total STAT3 levels. However, this effect was prevented by incubation with melatonin 1 mM. Furthermore, melatonin effects under hypoxia were similar to those observed when HepG2 cells were exposed to the selective STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic (Figures 3A and B), and combined treatment with both melatonin and Stattic resulted in a synergic inhibitory effect on Hif1α and phospho-STAT3 activation and VEGF expression.

Melatonin prevents hypoxia recruited STAT3/Hif1α/CBP/p300 within VEGF promoter. VEGF secreted protein from HepG2 cells under normoxia/hypoxia, with or without melatonin treatment and exposed to the selective STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic (A). Hif1α, phospho-STAT3, STAT3, and VEGF protein expression in HepG2 cells under normoxia/hypoxia, with or without melatonin treatment and exposed to the selective STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic (B). Effect of hypoxia and/or melatonin treatment on Hif1α, phospho-STAT3, and CBP/p300 association measured by co-immunoprecipitation (C). Effect of melatonin on Hif1α binding to VEGF promoter region analysed by ChIP. M: marker; IgG: Rabbit control IgG (D). Data are expressed as a percentage of mean values±s.e.m. of four experiments performed in triplicate. *p<0.05 significant differences vs control. #P<0.05 significant differences between CoCl2 and melatonin+CoCl2-treated cells.

Since both functional Hif1α and phospho-STAT3 are known to be required for high VEGF activity (Jung et al, 2005), and owing to the proximity of their binding sites within VEGF promoter, they are assumed to share a transcriptional complex together with CBP/p300. To analyse melatonin ability to disrupt the stability of this complex, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assay. As shown in Figure 3C CoCl2 treatment resulted in increased association between Hif1α, phospho-STAT3, and CBP/p300, confirming that they are likely linked. Furthermore, our results suggest that melatonin treatment inhibited this association and thus, VEGF transcriptional activation.

Although our data support the idea that melatonin prevents VEGF synthesis by blocking its transcription in HepG2 cells, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed under normoxia and hypoxia to investigate whether Hif1α occupancy of the VEGF promoter was affected by melatonin. As shown in Figure 3D. CoCl2-induced hypoxia resulted in enhanced promoter binding activity vs normoxia, and this effect was suppressed by 1 mM melatonin treatment.

Discussion

HCC is the most common liver cancer, and even been the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, effective therapy is currently lacking (Midorikawa et al, 2010). This type of cancer is considered as a hypervascular tumour, and angiogenesis has a critical role in HCC growth and progression (Wu et al, 2007). The high proliferation rate of tumour cells enhances local hypoxia within the HCC microenvironment; increasing new vessels formation for tumour oxygen and nutrients supply (Li et al, 2011), and allowing metastatic spreading by connection to the pre-existing vessels (Chekhonin et al, 2012). Although melatonin’s ability to suppress angiogenesis mainly through VEGF downregulation has been shown in other tumour types (Lissoni, 2002; Kim et al, 2013), there are no reports about its anti-angiogenic activity in liver cancer. In the present study, we used the human liver cancer cell line HepG2 and HUVEC to analyse the potential anti-angiogenic activity of melatonin in HCC.

As indicated above, VEGF is an important growth factor implicated in cancer angiogenesis and can also be used as a tumour marker (Kammerer et al, 2012; Marton et al, 2012). Different studies have suggested that targeting the VEGF pathway could be even more effective strategy that targeting the tumour itself, based on the fact that angiogenesis and hypervascularisation is a common denominator of solid tumours, regardless their etiological origin (Tabernero, 2007). In HCC, increased VEGF expression has been reported to correlate with tumour progression, microvessel invasion and metastasis of HCC (Sun and Tang, 2004), and VEGF serum measurement are accepted to indirectly estimate tissue values, providing useful prognostic information for HCC management (Poon et al, 2003). Although VEGF expression is driven by many factors, hypoxia seems to be the main regulator of its production (Ferrara, 2004). Results from the present study verified that incubation of cells with CoCl2 mimics the hypoxia situation, as confirmed by the observed increase of VEGF protein expression and secretion vs normoxia. Moreover, VEGF levels were effectively reduced by melatonin treatment, mainly at the tested pharmacological dose. Thus, and since microvessels density reflects tumour angiogenicity, and is considered vital for tumour prognostic (Kitamura et al, 2012; Sun et al, 2012), we performed in vitro tube formation assay, as a widely accepted approach to measure the reorganisation stage of angiogenesis, under our experimental conditions. Results showed that melatonin treatment decreased VEGF secretion by HepG2 cells; therefore, HUVECs cultured with CM from the melatonin treated group were unable to display its endothelial features. Similarly to our findings, melatonin has been previously shown to inhibit human pancreatic carcinoma cell PANC-1-induced HUVECs proliferation and migration by inhibiting VEGF expression (Cui et al, 2012).

Once confirmed the anti-angiogenic properties of melatonin, we focused on elucidating the responsible molecular mechanism. Results showed a hypoxia-dependent activation of VEGF transcriptional regulators, Hif1α and phospho-STAT3, which were also inhibited by melatonin at the pharmacologic concentration, 1 mM. The present data suggest that melatonin anti-angiogenic activity in liver cancer cells may be mediated, at least in part, by inhibition of Hif1α nuclear translocation, required for its transcriptional activation and subsequent VEGF expression. Moreover, results reported in other tumour types also point to melatonin ability to modulate Hif1α activity (Dai et al, 2008; Park et al, 2010; Cho et al, 2011; Alvarez-Garcia et al, 2012, 2013).

STAT3 has been shown to be a potential modulator of Hif1α-mediated VEGF expression, and the development of STAT3 inhibitors may be of interest for clinical treatment, especially of solid tumours (Jung et al, 2007). In this regard, molecules like betulinic acid, with anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties similar to melatonin, have been reported to suppress angiogenesis via STAT3 and Hif1α inhibition in PC-3 prostata cancer cells (Shin et al, 2011). Micro RNAs like miR-20b, which are known to regulate cellular processes such as proliferation and angiogenesis, have been documented to modulate VEGF expression by targeting HIF-1α and STAT3 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Cascio et al, 2010). Consistently, in the present study we observed a decrease of STAT3 activation after melatonin treatment. Combined treatment with the STAT3 inhibitor Stattic, known to prevent STAT3 activation, dimerisation and nuclear translocation (Schust et al, 2006); resulted in a synergic effect, with a decrease in VEGF production, via inhibition of the activation of Hif1α and STAT3 required for optimal VEGF synthesis. This suggests that melatonin anti-angiogenic effects may due to its ability to prevent STAT3 activation, which normally increases Hif1α stability and enhances its transcriptional activity.

Although previous studies reported that either Hif1α or STAT3 alone transcriptionally activate VEGF expression (Matsumura et al, 2012; Riddell et al, 2012), some evidence suggest that a maximal induction is reached when both transcription factors bind to the VEGF promoter, where they are presumably linked within the same transcriptional complex together with CBP/p300 co-activator (Gray et al, 2005; Rathinavelu et al, 2012). Considering the importance of this active complex for an efficient VEGF production, we hypothesised that melatonin effects could be related with its capacity to interrupt this transcriptional complex stability. Thus, while hypoxia induced by CoCl2 treatment resulted in increased association between Hif1α, phospho-STAT3, and CBP/p300, melatonin was able to prevent the physical interaction between these proteins, as confirmed by the immunoprecipitation assays. Moreover, our ChIP experiments revealed that Hif1α occupancy of the VEGF promoter was affected by melatonin treatment, providing final evidence to support a hypothetic model of melatonin inhibition of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in HCC, which is depicted in Figure 4. Results observed at the higher melatonin dose may be, in some aspect, related with the exceptionally high physiological concentrations of melatonin in the bile of mammals (Tan et al, 1999), suggesting that hepatocytes may have a particular ability to concentrate melatonin, and so pharmacologic doses may be especially effective in inhibiting liver cancer.

Model of melatonin inhibition of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in HCC. Hif1 is the major regulator of oxygen homeostasis. Whereas normoxia induces Hif1α proteosomal degradation, under hypoxia is stabilised and translocates to the nucleus where it forms a complex with phospho-STAT3 and CBP/p300 to upregulate VEGF expression, and thus hypoxia-induced angiogenesis. Melatonin pharmacological doses exert anti-angiogenic effects through inhibition of the previously described molecular mechanism.

Summarising, this is the first report showing that Hif1α and STAT3 transcription factors promote VEGF production in hypoxia-related angiogenesis in HCC. Considering the results from the current study and previous research data (Carbajo-Pescador et al, 2009, 2013), as well as the lack of toxicity of melatonin even at high doses, it seems reasonable to recommend further research to test the usefulness of the indole for the prevention and treatment of liver cancer in patients.

Change history

09 July 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Albini A, Tosetti F, Li VW, Noonan DM, Li WW (2012) Cancer prevention by targeting angiogenesis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9: 498–509.

Alvarez-Garcia V, Gonzalez A, Alonso-Gonzalez C, Martinez-Campa C, Cos S (2012) Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by melatonin in human breast cancer cells. J Pineal Res 54: 373–380.

Alvarez-Garcia V, Gonzalez A, Alonso-Gonzalez C, Martinez-Campa C, Cos S (2013) Antiangiogenic effects of melatonin in endothelial cell cultures. Microvasc Res 87: 25–33.

Bansal A (2009) Molecular mechanisms of acclimatization to high altitude hypoxia: role of hypoxia mimetic cobalt chloride. DRDO Science Spectrum 1: 172–179.

Benet M, Lahoz A, Guzman C, Castell JV, Jover R (2010) CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPalpha) and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (HNF4alpha) synergistically cooperate with constitutive androstane receptor to transactivate the human cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) gene: application to the development of a metabolically competent human hepatic cell model. J Biol Chem 285: 28457–28471.

Cabrera J, Negrin G, Estevez F, Loro J, Reiter RJ, Quintana J (2010) Melatonin decreases cell proliferation and induces melanogenesis in human melanoma SK-MEL-1 cells. J Pineal Res 49: 45–54.

Carbajo-Pescador S, Garcia-Palomo A, Martin-Renedo J, Piva M, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Mauriz JL (2011) Melatonin modulation of intracellular signaling pathways in hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cell line: role of the MT1 receptor. J Pineal Res 51: 463–471.

Carbajo-Pescador S, Martin-Renedo J, Garcia-Palomo A, Tunon MJ, Mauriz JL, Gonzalez-Gallego J (2009) Changes in the expression of melatonin receptors induced by melatonin treatment in hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells. J Pineal Res 47: 330–338.

Carbajo-Pescador S, Steinmetz C, Kashyap A, Lorenz S, Mauriz JL, Heise M, Galle PR, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Strand S (2013) Melatonin induces transcriptional regulation of Bim by FoxO3a in HepG2 cells. Br J Cancer 108: 442–449.

Cascio S, D'Andrea A, Ferla R, Surmacz E, Gulotta E, Amodeo V, Bazan V, Gebbia N, Russo A (2010) miR-20b modulates VEGF expression by targeting HIF-1 alpha and STAT3 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 224: 242–249.

Chekhonin VP, Shein SA, Korchagina AA, Gurina OI (2012) VEGF in tumor progression and targeted therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 53: 389–413.

Chiu CC, Chen JY, Lin KL, Huang CJ, Lee JC, Chen BH, Chen WY, Lo YH, Chen YL, Tseng CH, Chen YL, Lin SR (2010) p38 MAPK and NF-kappaB pathways are involved in naphtho[1,2-b] furan-4,5-dione induced anti-proliferation and apoptosis of human hepatoma cells. Cancer Lett 295: 92–99.

Cho SY, Lee HJ, Jeong SJ, Lee HJ, Kim HS, Chen CY, Lee EO, Kim SH (2011) Sphingosine kinase 1 pathway is involved in melatonin-induced HIF-1alpha inactivation in hypoxic PC-3 prostate cancer cells. J Pineal Res 51: 87–93.

Cini G, Neri B, Pacini A, Cesati V, Sassoli C, Quattrone S, D'Apolito M, Fazio A, Scapagnini G, Provenzani A, Quattrone A (2005) Antiproliferative activity of melatonin by transcriptional inhibition of cyclin D1 expression: a molecular basis for melatonin-induced oncostatic effects. J Pineal Res 39: 12–20.

Cornella H, Alsinet C, Villanueva A (2011) Molecular Pathogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 821–825.

Crespo I, Garcia-Mediavilla MV, Almar M, Gonzalez P, Tunon MJ, Sanchez-Campos S, Gonzalez-Gallego J (2008) Differential effects of dietary flavonoids on reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generation and changes in antioxidant enzyme expression induced by proinflammatory cytokines in Chang Liver cells. Food Chem Toxicol 46: 1555–1569.

Cui P, Yu M, Peng X, Dong L, Yang Z (2012) Melatonin prevents human pancreatic carcinoma cell PANC-1-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cell proliferation and migration by inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J Pineal Res 52: 236–243.

Dai M, Cui P, Yu M, Han J, Li H, Xiu R (2008) Melatonin modulates the expression of VEGF and HIF-1 alpha induced by CoCl2 in cultured cancer cells. J Pineal Res 44: 121–126.

Farriol M, Venereo Y, Orta X, Castellanos JM, Segovia-Silvestre T (2000) In vitro effects of melatonin on cell proliferation in a colon adenocarcinoma line. J Appl Toxicol 20: 21–24.

Ferrara N (2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev 25: 581–611.

Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J (2003) The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med 9: 669–676.

Futagami M, Sato S, Sakamoto T, Yokoyama Y, Saito Y (2001) Effects of melatonin on the proliferation and cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (CDDP) sensitivity of cultured human ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol 82: 544–549.

Garcia-Navarro A, Gonzalez-Puga C, Escames G, Lopez LC, Lopez A, Lopez-Cantarero M, Camacho E, Espinosa A, Gallo MA, Acuna-Castroviejo D (2007) Cellular mechanisms involved in the melatonin inhibition of HT-29 human colon cancer cell proliferation in culture. J Pineal Res 43: 195–205.

Garcia-Santos G, Antolin I, Herrera F, Martin V, Rodriguez-Blanco J, del Pilar Carrera M, Rodriguez C (2006) Melatonin induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cancer cells. J Pineal Res 41: 130–135.

Gonzalez A, Del Castillo-Vaquero A, Miro-Moran A, Tapia JA, Salido GM (2010) Melatonin reduces pancreatic tumor cell viability by altering mitochondrial physiology. J Pineal Res 50: 250–260.

Gray MJ, Zhang J, Ellis LM, Semenza GL, Evans DB, Watowich SS, Gallick GE (2005) HIF-1alpha, STAT3, CBP/p300 and Ref-1/APE are components of a transcriptional complex that regulates Src-dependent hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF in pancreatic and prostate carcinomas. Oncogene 24: 3110–3120.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144: 646–674.

Hill SM, Blask DE (1988) Effects of the pineal hormone melatonin on the proliferation and morphological characteristics of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) in culture. Cancer Res 48: 6121–6126.

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350: 2335–2342.

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61: 69–90.

Ji J, Wang XW (2012) Clinical implications of cancer stem cell biology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol 39: 461–472.

Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, Herbst RS, Nemunaitis JJ, Jablons DM, Langer CJ, DeVore RF 3rd, Gaudreault J, Damico LA, Holmgren E, Kabbinavar F (2004) Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 2184–2191.

Jung JE, Kim HS, Lee CS, Park DH, Kim YN, Lee MJ, Lee JW, Park JW, Kim MS, Ye SK, Chung MH (2007) Caffeic acid and its synthetic derivative CADPE suppress tumor angiogenesis by blocking STAT3-mediated VEGF expression in human renal carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis 28: 1780–1787.

Jung JE, Lee HG, Cho IH, Chung DH, Yoon SH, Yang YM, Lee JW, Choi S, Park JW, Ye SK, Chung MH (2005) STAT3 is a potential modulator of HIF-1-mediated VEGF expression in human renal carcinoma cells. FASEB J 19: 1296–1298.

Kammerer PW, Koch FP, Schiegnitz E, Kumar VV, Berres M, Toyoshima T, Al-Nawas B, Brieger J (2012) Associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the VEGF gene and long-term prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med 42: 374–381.

Kim KJ, Choi JS, Kang I, Kim KW, Jeong CH, Jeong JW (2013) Melatonin suppresses tumor progression by reducing angiogenesis stimulated by HIF-1 in a mouse tumor model. J Pineal Res 54: 264–270.

Kitamura H, Koike S, Nakazawa K, Matsumura H, Yokoi K, Nakagawa K, Arai M (2012) A reversal in the vascularity of metastatic liver tumors from colorectal cancer after the cessation of chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and histological examination. J Surg Oncol 107: 155–159.

Li S, Yao D, Wang L, Wu W, Qiu L, Yao M, Yao N, Zhang H, Yu D, Ni Q (2011) Expression characteristics of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and its clinical values in diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Mon 11: 821–828.

Lissoni P (2002) Is there a role for melatonin in supportive care? Support Care Cancer 10: 110–116.

Lissoni P, Rovelli F, Malugani F, Bucovec R, Conti A, Maestroni GJ (2001) Anti-angiogenic activity of melatonin in advanced cancer patients. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 22: 45–47.

Martin-Renedo J, Mauriz JL, Jorquera F, Ruiz-Andres O, Gonzalez P, Gonzalez-Gallego J (2008) Melatonin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cell line. J Pineal Res 45: 532–540.

Marton I, Knezevic F, Ramic S, Milosevic M, Tomas D (2012) Immunohistochemical expression and prognostic significance of HIF-1alpha and VEGF-C in neuroendocrine breast cancer. Anticancer Res 32: 5227–5232.

Matsumura A, Kubota T, Taiyoh H, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Ichikawa D, Shiozaki A, Komatsu S, Nakanishi M, Kuriu Y, Murayama Y, Ikoma H, Ochiai T, Kokuba Y, Nakamura T, Matsumoto K, Otsuji E (2012) HGF regulates VEGF expression via the c-Met receptor downstream pathways, PI3K/Akt, MAPK and STAT3, in CT26 murine cells. Int J Oncol 42: 535–542.

Mauriz JL, Molpeceres V, Garcia-Mediavilla MV, Gonzalez P, Barrio JP, Gonzalez-Gallego J (2007) Melatonin prevents oxidative stress and changes in antioxidant enzyme expression and activity in the liver of aging rats. J Pineal Res 42: 222–230.

Midorikawa Y, Sugiyama Y, Aburatani H (2010) Molecular targets for liver cancer therapy: from screening of target genes to clinical trials. Hepatol Res 40: 49–60.

Niu G, Briggs J, Deng J, Ma Y, Lee H, Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Kay H, Cress WD, Jove R, Yu H (2008) Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is required for hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha RNA expression in both tumor cells and tumor-associated myeloid cells. Mol Cancer Res 6: 1099–1105.

Park SY, Jang WJ, Yi EY, Jang JY, Jung Y, Jeong JW, Kim YJ (2010) Melatonin suppresses tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting HIF-1alpha stabilization under hypoxia. J Pineal Res 48: 178–184.

Poon RT, Lau CP, Cheung ST, Yu WC, Fan ST (2003) Quantitative correlation of serum levels and tumor expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 63: 3121–3126.

Rathinavelu A, Narasimhan M, Muthumani P (2012) A novel regulation of VEGF expression by HIF-1alpha and STAT3 in HDM2 transfected prostate cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med 16: 1750–1757.

Riddell JR, Maier P, Sass SN, Moser MT, Foster BA, Gollnick SO (2012) Peroxiredoxin 1 Stimulates Endothelial Cell Expression of VEGF via TLR4 Dependent Activation of HIF-1alpha. PLoS ONE 7: e50394.

Schust J, Sperl B, Hollis A, Mayer TU, Berg T (2006) Stattic: a small-molecule inhibitor of STAT3 activation and dimerization. Chem Biol 13: 1235–1242.

Sengupta B, Siddiqi SA (2012) Hepatocellular carcinoma: important biomarkers and their significance in molecular diagnostics and therapy. Curr Med Chem 19: 3722–3729.

Shin J, Lee HJ, Jung DB, Jung JH, Lee HJ, Lee EO, Lee SG, Shim BS, Choi SH, Ko SG, Ahn KS, Jeong SJ, Kim SH (2011) Suppression of STAT3 and HIF-1 alpha mediates anti-angiogenic activity of betulinic acid in hypoxic PC-3 prostate cancer cells. PLoS ONE 6: e21492.

Sun HC, Tang ZY (2004) Angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: the retrospectives and perspectives. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 130: 307–319.

Sun XT, Yuan XW, Zhu HT, Deng ZM, Yu DC, Zhou X, Ding YT (2012) Endothelial precursor cells promote angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 18: 4925–4933.

Tabernero J (2007) The role of VEGF and EGFR inhibition: implications for combining anti-VEGF and anti-EGFR agents. Mol Cancer Res 5: 203–220.

Tan D, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ, Qi W, Hanes MA, Farley NJ (1999) High physiological levels of melatonin in the bile of mammals. Life Sci 65: 2523–2529.

Tischer E, Mitchell R, Hartman T, Silva M, Gospodarowicz D, Fiddes JC, Abraham JA (1991) The human gene for vascular endothelial growth factor. Multiple protein forms are encoded through alternative exon splicing. J Biol Chem 266: 11947–11954.

Vaupel P (2004) The role of hypoxia-induced factors in tumor progression. Oncologist 9: 10–17.

Wang X, Crowe PJ, Goldstein D, Yang JL (2012) STAT3 inhibition, a novel approach to enhancing targeted therapy in human cancers (Review). Int J Oncol 41: 1181–1191.

Wu XZ, Xie GR, Chen D (2007) Hypoxia and hepatocellular carcinoma: the therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22: 1178–1182.

Zha L, Fan L, Sun G, Wang H, Ma T, Zhong F, Wei W (2012) Melatonin sensitizes human hepatoma cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Pineal Res 52: 322–331.

Acknowledgements

Sara Carbajo-Pescador is granted by the Consejería de Educación (Junta de Castilla y León, Spain) and Fondo Social Europeo. Raquel Ordoñez is granted by the program Formación del Profesorado Universitario from the Ministry of Education (Spain). Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd) is funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III. This work has been partially supported by Fundación Investigación Sanitaria en León. All experiments comply with the current laws of Spain and the European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Carbajo-Pescador, S., Ordoñez, R., Benet, M. et al. Inhibition of VEGF expression through blockade of Hif1α and STAT3 signalling mediates the anti-angiogenic effect of melatonin in HepG2 liver cancer cells. Br J Cancer 109, 83–91 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.285

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.285

Keywords

This article is cited by

Anti-drug resistance, anti-inflammation, and anti-proliferation activities mediated by melatonin in doxorubicin-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma: in vitro investigations

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2023)

A novel HIF1α-STIL-FOXM1 axis regulates tumor metastasis

Journal of Biomedical Science (2022)

Membrane progesterone receptor α (mPRα) enhances hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor secretion and angiogenesis in lung adenocarcinoma through STAT3 signaling

Journal of Translational Medicine (2022)

Hypoxia Modulates Melanoma Cells Proliferation and Apoptosis via miRNA-210/ISCU/ROS Signaling

Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine (2022)

Anlotinib combined with temozolomide suppresses glioblastoma growth via mediation of JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2022)