Key Points

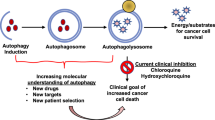

Macroautophagy (known as autophagy) is a highly regulated multi-step process that is involved in the bulk degradation of cellular proteins and organelles to provide macromolecular precursors that are recycled or that are used to fuel metabolic pathways.

Autophagy can be targeted for both stimulation and inhibition. Stimulation can be achieved through cellular stress (nutrient deprivation) and mTOR inhibition, and inhibition can be achieved through multiple targets both upstream (ULK1, Beclin 1 and VPS34 inhibitors) and downstream of the site of lysosomal fusion with the autophagosome.

Early clinical trials have demonstrated the feasibility and potential benefit of clinically inhibiting autophagy in multiple cancer types, including glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, melanoma, sarcoma and multiple myeloma.

Ongoing studies are developing novel clinical biomarkers that can be used to monitor autophagy in patients, including electron microscopy evaluation of autophagosome number in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumour samples, LC3II and ATG13 puncta by immunohistochemistry, and novel imaging techniques that use positron emission tomography and metabolomics profiles.

The role of autophagy in regulating tumour immune responses is unclear, with arguments both for and against autophagy inhibition. Further research is needed to define the safety and utility of autophagy inhibition while also maximizing tumour immune responses for improved clinical outcomes.

Markers of autophagy dependence have the potential to identify patients who will best respond to autophagy inhibition therapy. Such markers include altered RAS signalling, BRAF mutations, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation, autophagy-dependent secretion of interleukins and p53 status.

Autophagy can be an effective cancer escape mechanism and has been implicated in the development of resistance in multiple cancer types, including BRAF-mutated central nervous system (CNS) tumours and melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), bladder cancer and thyroid cancer. Combination therapy with autophagy inhibition in these cancers has the potential to reduce and reverse resistance to therapy.

Abstract

Autophagy is a mechanism by which cellular material is delivered to lysosomes for degradation, leading to the basal turnover of cell components and providing energy and macromolecular precursors. Autophagy has opposing, context-dependent roles in cancer, and interventions to both stimulate and inhibit autophagy have been proposed as cancer therapies. This has led to the therapeutic targeting of autophagy in cancer to be sometimes viewed as controversial. In this Review, we suggest a way forwards for the effective targeting of autophagy by understanding the context-dependent roles of autophagy and by capitalizing on modern approaches to clinical trial design.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Klionsky, D. J. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 931–937 (2007).

The Nobel Assembly. The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet has today decided to award the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Yoshinori Ohsumi https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2016/press.html (2016).

Amaravadi, R., Kimmelman, A. C. & White, E. Recent insights into the function of autophagy in cancer. Genes Dev. 30, 1913–1930 (2016).

White, E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 401–410 (2012).

Galluzzi, L. et al. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J. http://dx.doi.org/10.15252/embj.201490784 (2015).

Levy, J. M. & Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy during cancer therapy to improve clinical outcomes. Pharmacol. Ther. 131, 130–141 (2011).

Towers, C. G. & Thorburn, A. Therapeutic targeting of autophagy. EBioMedicine 14, 15–23 (2016).

Mizushima, N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 21, 2861–2873 (2007).

Mizushima, N., Yoshimori, T. & Ohsumi, Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 107–132 (2011). A detailed discussion of the protein and membrane interactions required for autophagosome formation.

Liang, X. H. et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 402, 672–676 (1999). Beclin 1 is identified as a putative tumour suppressor.

Klionsky, D. J. et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 12, 1–222 (2016). The definitive consensus of experimental methods that are appropriate for the study of autophagy.

Bago, R. et al. Characterization of VPS34-IN1, a selective inhibitor of Vps34, reveals that the phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-binding SGK3 protein kinase is a downstream target of class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 463, 413–427 (2014).

Dowdle, W. E. et al. Selective VPS34 inhibitor blocks autophagy and uncovers a role for NCOA4 in ferritin degradation and iron homeostasis in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 1069–1079 (2014).

Ronan, B. et al. A highly potent and selective Vps34 inhibitor alters vesicle trafficking and autophagy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 1013–1019 (2014).

Egan, D. F. et al. Small molecule inhibition of the autophagy kinase ULK1 and identification of ULK1 substrates. Mol. Cell 59, 285–297 (2015).

Petherick, K. J. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of ULK1 kinase blocks mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 11376–11383 (2015).

Akin, D. et al. A novel ATG4B antagonist inhibits autophagy and has a negative impact on osteosarcoma tumors. Autophagy 10, 2021–2035 (2014).

McAfee, Q. et al. Autophagy inhibitor Lys05 has single-agent antitumor activity and reproduces the phenotype of a genetic autophagy deficiency. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8253–8258 (2012).

Goodall, M. L. et al. Development of potent autophagy inhibitors that sensitize oncogenic BRAF V600E mutant melanoma tumor cells to vemurafenib. Autophagy 10, 1120–1136 (2014).

Malik, S. A. et al. BH3 mimetics activate multiple pro-autophagic pathways. Oncogene 30, 3918–3929 (2011).

Nazio, F. et al. mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self-association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 406–416 (2013).

DeBosch, B. J. et al. Trehalose inhibits solute carrier 2A (SLC2A) proteins to induce autophagy and prevent hepatic steatosis. Sci. Signal. 9, ra21 (2016).

Marino, G., Pietrocola, F., Madeo, F. & Kroemer, G. Caloric restriction mimetics: natural/physiological pharmacological autophagy inducers. Autophagy 10, 1879–1882 (2014).

He, C. et al. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature 481, 511–515 (2012).

Li, W. W., Li, J. & Bao, J. K. Microautophagy: lesser-known self-eating. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 1125–1136 (2012).

Arias, E. & Cuervo, A. M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy in protein quality control. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 184–189 (2011).

Kaushik, S. et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 124, 495–499 (2011).

Kon, M. et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy is required for tumor growth. Sci. Transl Med. 3, 109ra117 (2011).

Mancias, J. D., Wang, X., Gygi, S. P., Harper, J. W. & Kimmelman, A. C. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 509, 105–109 (2014).

Dou, Z. et al. Autophagy mediates degradation of nuclear lamina. Nature 527, 105–109 (2015).

Amaravadi, R. K. et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 326–336 (2007). Therapy with autophagy inhibition is identified as having combinatory effects with other anticancer agents.

Thorburn, A., Thamm, D. H. & Gustafson, D. L. Autophagy and cancer therapy. Mol. Pharmacol. 85, 830–838 (2014).

Yang, Y. P. et al. Application and interpretation of current autophagy inhibitors and activators. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34, 625–635 (2013).

Maycotte, P. et al. Chloroquine sensitizes breast cancer cells to chemotherapy independent of autophagy. Autophagy 8, 200–212 (2012).

Eng, C. H. et al. Macroautophagy is dispensable for growth of KRAS mutant tumors and chloroquine efficacy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 182–187 (2016).

Maes, H. et al. Tumor vessel normalization by chloroquine independent of autophagy. Cancer Cell 26, 190–206 (2014).

Briceno, E., Reyes, S. & Sotelo, J. Therapy of glioblastoma multiforme improved by the antimutagenic chloroquine. Neurosurg. Focus 14, e3 (2003). The results of the first clinical trial to evaluate the antitumour effects of CQ, which showed improved clinical outcomes with autophagy inhibition in glioblastoma.

Briceno, E., Calderon, A. & Sotelo, J. Institutional experience with chloroquine as an adjuvant to the therapy for glioblastoma multiforme. Surg. Neurol. 67, 388–391 (2007).

Sotelo, J., Briceno, E. & Lopez-Gonzalez, M. A. Adding chloroquine to conventional treatment for glioblastoma multiforme: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 144, 337–343 (2006).

Eldredge, H. B. et al. Concurrent whole brain radiotherapy and short-course chloroquine in patients with brain metastases: a pilot trial. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2, 315–321 (2013).

Rojas-Puentes, L. L. et al. Phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of whole-brain irradiation with concomitant chloroquine for brain metastases. Radiat. Oncol. 8, 209 (2013).

Barnard, R. A. et al. Phase I clinical trial and pharmacodynamic evaluation of combination hydroxychloroquine and doxorubicin treatment in pet dogs treated for spontaneously occurring lymphoma. Autophagy 10, 1415–1425 (2014).

Mahalingam, D. et al. Combined autophagy and HDAC inhibition: a phase I safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic analysis of hydroxychloroquine in combination with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat in patients with advanced solid tumors. Autophagy 10, 1403–1414 (2014).

Rangwala, R. et al. Combined MTOR and autophagy inhibition: Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine and temsirolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy 10, 1391–1402 (2014).

Rangwala, R. et al. Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine with dose-intense temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy 10, 1369–1379 (2014).

Rosenfeld, M. R. et al. A phase I/II trial of hydroxychloroquine in conjunction with radiation therapy and concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Autophagy 10, 1359–1368 (2014).

Vogl, D. T. et al. Combined autophagy and proteasome inhibition: A phase 1 trial of hydroxychloroquine and bortezomib in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma. Autophagy 10, 1380–1390 (2014).

Wolpin, B. M. et al. Phase II and pharmacodynamic study of autophagy inhibition using hydroxychloroquine in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist 19, 637–638 (2014).

Karsli-Uzunbas, G. et al. Autophagy is required for glucose homeostasis and lung tumor maintenance. Cancer Discov. 4, 914–927 (2014). An evaluation of the genetic knockout of autophagy-related genes and the growth of tumour cells in vivo , and the identification of a therapeutic window to inhibit autophagy in lung cancer growth and development.

Pellegrini, P. et al. Acidic extracellular pH neutralizes the autophagy-inhibiting activity of chloroquine: implications for cancer therapies. Autophagy 10, 562–571 (2014).

Wang, T. et al. Synthesis of improved lysomotropic autophagy inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 58, 3025–3035 (2015).

Yang, A. et al. Autophagy is critical for pancreatic tumor growth and progression in tumors with p53 alterations. Cancer Discov. 4, 905–913 (2014).

Boone, B. A. et al. Safety and biologic response of pre-operative autophagy inhibition in combination with gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22, 4402–4410 (2015).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01881451?term=NCT01881451&rank=1(2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02233387?term=NCT02233387&rank=1(2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01206530?term=NCT01206530&rank=1 (2017).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02042989?term=NCT02042989&rank=1(2017).

Fullgrabe, J., Heldring, N., Hermanson, O. & Joseph, B. Cracking the survival code: autophagy-related histone modifications. Autophagy 10, 556–561 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Next-generation proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 sensitizes breast cancer cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 6, 26456 (2016).

Perera, R. M. et al. Transcriptional control of autophagy-lysosome function drives pancreatic cancer metabolism. Nature 524, 361–365 (2015).

Follo, C., Barbone, D., Richards, W. G., Bueno, R. & Broaddus, V. C. Autophagy initiation correlates with the autophagic flux in 3D models of mesothelioma and with patient outcome. Autophagy 12, 1180–1194 (2016).

Lock, R., Kenific, C. M., Leidal, A. M., Salas, E. & Debnath, J. Autophagy-dependent production of secreted factors facilitates oncogenic RAS-driven invasion. Cancer Discov. 4, 466–479 (2014).

Kraya, A. A. et al. Identification of secreted proteins that reflect autophagy dynamics within tumor cells. Autophagy 11, 60–74 (2015).

Maycotte, P., Jones, K. L., Goodall, M. L., Thorburn, J. & Thorburn, A. Autophagy supports breast cancer stem cell maintenance by regulating IL6 secretion. Mol. Cancer Res. 4, 651–658 (2015).

Varadarajulu, S. & Bang, J. Y. Role of endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the clinical assessment of pancreatic neoplasms. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 25, 255–272 (2016).

Feng, Y., He, D., Yao, Z. & Klionsky, D. J. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 24, 24–41 (2014). Basic review of the history and core machinery involved in the process of autophagy.

Altman, J. K. et al. Autophagy is a survival mechanism of acute myelogenous leukemia precursors during dual mTORC2/mTORC1 targeting. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 2400–2409 (2014).

Kun, Z. et al. Gastrin enhances autophagy and promotes gastric carcinoma proliferation via inducing AMPKα. Oncol. Res. http://dx.doi.org/10.3727/096504016X14823648620870 (2017).

Masui, A. et al. Autophagy as a survival mechanism for squamous cell carcinoma cells in endonuclease G-mediated apoptosis. PLoS ONE 11, e0162786 (2016).

Tan, Q. et al. Role of autophagy as a survival mechanism for hypoxic cells in tumors. Neoplasia 18, 347–355 (2016).

Fitzwalter, B. E. & Thorburn, A. Recent insights into cell death and autophagy. FEBS J. 282, 4279–4288 (2015).

Gump, J. M. et al. Autophagy variation within a cell population determines cell fate through selective degradation of Fap-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 47–54 (2014).

Thorburn, J. et al. Autophagy controls the kinetics and extent of mitochondrial apoptosis by regulating PUMA levels. Cell Rep. 7, 45–52 (2014).

Goodall, M. L. et al. The autophagy machinery controls cell death switching between apoptosis and necroptosis. Dev. Cell 37, 337–349 (2016).

Rao, S., Yang, H., Penninger, J. M. & Kroemer, G. Autophagy in non-small cell lung carcinogenesis: a positive regulator of antitumor immunosurveillance. Autophagy 10, 529–531 (2014).

Ma, Y., Galluzzi, L., Zitvogel, L. & Kroemer, G. Autophagy and cellular immune responses. Immunity 39, 211–227 (2013).

Townsend, K. N. et al. Autophagy inhibition in cancer therapy: metabolic considerations for antitumor immunity. Immunol. Rev. 249, 176–194 (2012).

Ko, A. et al. Autophagy inhibition radiosensitizes in vitro, yet reduces radioresponses in vivo due to deficient immunogenic signalling. Cell Death Differ. 21, 92–99 (2014).

Michaud, M. et al. Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science 334, 1573–1577 (2011).

Lechner, M. G. et al. Immunogenicity of murine solid tumor models as a defining feature of in vivo behavior and response to immunotherapy. J. Immunother. 36, 477–489 (2013).

Starobinets, H. et al. Antitumor adaptive immunity remains intact following inhibition of autophagy and antimalarial treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 4417–4429 (2016).

Pietrocola, F. et al. Caloric restriction mimetics enhance anticancer immunosurveillance. Cancer Cell 30, 147–160 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. The vitamin E analogue α-TEA stimulates tumor autophagy and enhances antigen cross-presentation. Cancer Res. 72, 3535–3545 (2012).

Ladoire, S. et al. Combined evaluation of LC3B puncta and HMGB1 expression predicts residual risk of relapse after adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Autophagy 11, 1878–1890 (2015).

Ladoire, S. et al. The presence of LC3B puncta and HMGB1 expression in malignant cells correlate with the immune infiltrate in breast cancer. Autophagy 12, 864–875 (2016).

Baginska, J. et al. Granzyme B degradation by autophagy decreases tumor cell susceptibility to natural killer-mediated lysis under hypoxia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17450–17455 (2013).

Liang, X. et al. Inhibiting systemic autophagy during interleukin 2 immunotherapy promotes long-term tumor regression. Cancer Res. 72, 2791–2801 (2012).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03057340?term=NCT03057340&rank=1 (2017).

Page, D. B. et al. Glimpse into the future: harnessing autophagy to promote anti-tumor immunity with the DRibbles vaccine. J. Immunother. Cancer 4, 25 (2016).

Yu, G. L. et al. Combinational immunotherapy with allo-DRibble vacciens and anti-OX40 co-stimulation leads to generation of cross-reactive effector T cells and tumor regression. Sci. Rep. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep37558 (2016).

Hilton, T. S. et al. Preliminary analysis of immune responses in patients enrolled in a Phase II trial of cyclophosphamide wiht allogenic DRibble vaccine alone (DPV-001) or with GM-CSF or imiquimod for adjuvant treatment of stage IIIA or IIIB NSCLC. J. Immunother. Cancer 2, 249 (2014).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01956734?term=NCT01956734&rank=1 (2015).

Levy, J. M. M. et al. Autophagy inhibition improves chemosensitivity in BRAFV600E brain tumors. Cancer Discov. 4, 773–780 (2014).

Maycotte, P. et al. STAT3-mediated autophagy dependence identifies subtypes of breast cancer where autophagy inhibition can be efficacious. Cancer Res. 74, 2579–2590 (2014).

Guo, J. Y. et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 25, 460–470 (2011).

Lock, R. et al. Autophagy facilitates glycolysis during Ras-mediated oncogenic transformation. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 165–178 (2011).

Yang, S. et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev. 25, 717–729 (2011).

Sousa, C. M. et al. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature 536, 479–483 (2016).

Strohecker, A. M. et al. Autophagy sustains mitochondrial glutamine metabolism and growth of BrafV600E-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 3, 1272–1285 (2013).

Xie, X., Koh, J. Y., Price, S., White, E. & Mehnert, J. M. Atg7 overcomes senescence and promotes growth of BrafV600E-driven melanoma. Cancer Discov. 5, 410–423 (2015).

Mancias, J. D. & Kimmelman, A. C. Targeting autophagy addiction in cancer. Oncotarget 2, 1302–1306 (2011).

Thorburn, A. & Morgan, M. J. Targeting autophagy in BRAF-mutant tumors. Cancer Discov. 5, 353–354 (2015).

Levine, B. & Abrams, J. p53: the Janus of autophagy? Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 637–639 (2008).

Tang, J. Di, J., Cao, H., Bai, J. & Zheng, J. p53-mediated autophagic regulation: a prospective strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 363, 101–107 (2015).

Rosenfeldt, M. T. et al. p53 status determines the role of autophagy in pancreatic tumour development. Nature 504, 296–300 (2013).

Iacobuzio-Donahue, C. A. & Herman, J. M. Autophagy, p53, and pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1352–1353 (2014).

Huo, Y. et al. Autophagy opposes p53-mediated tumor barrier to facilitate tumorigenesis in a model of PALB2-associated hereditary breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 3, 894–907 (2013).

Morgan, M. J. et al. Regulation of autophagy and chloroquine sensitivity by oncogenic RAS in vitro is context-dependent. Autophagy 10, 1814–1826 (2014).

Vasilevskaya, I. A., Selvakumaran, M., Roberts, D. & O'Dwyer, P. J. JNK1 inhibition attenuates hypoxia-induced autophagy and sensitizes to chemotherapy. Mol. Cancer Res. 14, 753–763 (2016).

Jutten, B. & Rouschop, K. M. EGFR signaling and autophagy dependence for growth, survival, and therapy resistance. Cell Cycle 13, 42–51 (2014).

Guo, D. et al. The AMPK agonist AICAR inhibits the growth of EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastomas by inhibiting lipogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12932–12937 (2009).

Jutten, B. et al. EGFR overexpressing cells and tumors are dependent on autophagy for growth and survival. Radiother. Oncol. 108, 479–483 (2013).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02257424?term=NCT02257424&rank=1 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02378532?term=NCT02378532&rank=1 (2016).

Ma, X.-H. et al. Targeting ER stress-induced autophagy overcomes BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1406–1417 (2014).

Mulcahy Levy, J. M. et al. Autophagy inhibition overcomes multiple mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibition in brain tumors. eLife 6, e19671 (2017). The first demonstration of the use of autophagy inhibition to overcome kinase inhibitor resistance in patients.

Kang, M. et al. Concurrent autophagy inhibition overcomes the resistance of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in human bladder cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 321 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Targeting autophagy sensitizes BRAF-mutant thyroid cancer to vemurafenib. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102, 634–643 (2016).

Liu, J. T. et al. Autophagy inhibition overcomes the antagonistic effect between gefitinib and cisplatin in epidermal growth factor receptor mutant non–small-cell lung cancer cells. Clin. Lung Cancer 16, e55–e66 (2015).

Zou, Y. et al. The autophagy inhibitor chloroquine overcomes the innate resistance of wild-type EGFR non-small-cell lung cancer cells to erlotinib. J. Thorac Oncol. 8, 693–702 (2013).

Ji, C. et al. Induction of autophagy contributes to crizotinib resistance in ALK-positive lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 15, 570–577 (2014).

Zhang, S. F. et al. TXNDC17 promotes paclitaxel resistance via inducing autophagy in ovarian cancer. Autophagy 11, 225–238 (2015).

Wang, J. & Wu, G. S. Role of autophagy in cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 17163–17173 (2014).

Yu, L. et al. Induction of autophagy counteracts the anticancer effect of cisplatin in human esophageal cancer cells with acquired drug resistance. Cancer Lett. 355, 34–45 (2014).

Wu, H. M., Jiang, Z. F., Ding, P. S., Shao, L. J. & Liu, R. Y. Hypoxia-induced autophagy mediates cisplatin resistance in lung cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 12291 (2015).

Mahoney, E. et al. ER stress and autophagy: new discoveries in the mechanism of action and drug resistance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol. Blood 120, 1262–1273 (2012).

Li, Z. Y. et al. A novel HDAC6 inhibitor Tubastatin A: controls HDAC6-p97/VCP-mediated ubiquitination-autophagy turnover and reverses Temozolomide-induced ER stress-tolerance in GBM cells. Cancer Lett. 391, 89–99 (2017).

Aveic, S. & Tonini, G. P. Resistance to receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in solid tumors: can we improve the cancer fighting strategy by blocking autophagy? Cancer Cell. Int. 16, 62 (2016).

Chen, S. et al. Autophagy is a therapeutic target in anticancer drug resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1806, 220–229 (2010).

Kumar, A., Singh, U. K. & Chaudhary, A. Targeting autophagy to overcome drug resistance in cancer therapy. Future Med. Chem. 7, 1535–1542 (2015).

Sannigrahi, M. K., Singh, V., Sharma, R., Panda, N. K. & Khullar, M. Role of autophagy in head and neck cancer and therapeutic resistance. Oral Dis. 21, 283–291 (2015).

Sui, X. et al. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 4, e838 (2013).

Viale, A. et al. Oncogene ablation-resistant pancreatic cancer cells depend on mitochondrial function. Nature 514, 628–632 (2014).

Katheder, N. S. et al. Microenvironmental autophagy promotes tumour growth. Nature 541, 417–420 (2017).

Pasquier, B. Autophagy inhibitors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 985–1001 (2016).

Basit, F., Cristofanon, S. & Fulda, S. Obatoclax (GX15-070) triggers necroptosis by promoting the assembly of the necrosome on autophagosomal membranes. Cell Death Differ. 20, 1161–1173 (2013).

Chen, H. Y. & White, E. Role of autophagy in cancer prevention. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 4, 973–983 (2011).

Bedoya, V. Effect of chloroquine on malignant lymphoreticular and pigmented cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 30, 1262–1275 (1970). The anti-malarial drug CQ is first shown to inhibit tumour cell growth in vitro , as indicated by the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles.

Funakoshi, T., Matsuura, A., Noda, T. & Ohsumi, Y. Analyses of APG13 gene involved in autophagy in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 192, 207–213 (1997). The Ohsumi group cloned the first autophagy- specific gene, Apg13 in yeast ( ATG1 in humans).

Matsuura, A., Tsukada, M., Wada, Y. & Ohsumi, Y. Apg1p, a novel protein kinase required for the autophagic process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 192, 245–250 (1997). The Ohsumi group demonstrated the direct involvement of protein phosphorylation in the regulation of autophagy.

Mizushima, N., Sugita, H., Yoshimori, T. & Ohsumi, Y. A new protein conjugation system in human. The counterpart of the yeast Apg12p conjugation system essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33889–33892 (1998). The first autophagy-specific genes in higher eukaryotes were identified.

Murakami, N. et al. Accumulation of tau in autophagic vacuoles in chloroquine myopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 57, 664–673 (1998). The first study to observe that CQ can inhibit autophagy and the connection between the accumulation of cellular proteins and the inhibition of lysosomal degradation.

Kuma, A. et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432, 1032–1036 (2004). The first autophagy-deficient mouse ( Atg5−/−) was created, and indicated that autophagy is important during development.

Rao, S. et al. A dual role for autophagy in a murine model of lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 5, 3056 (2014). In vivo model that demonstrated the ability of autophagy to repress early oncogenesis but to support late-stage cancer growth.

Chi, K. H. et al. Addition of rapamycin and hydroxychloroquine to metronomic chemotherapy as a second line treatment results in high salvage rates for refractory metastatic solid tumors: a pilot safety and effectiveness analysis in a small patient cohort. Oncotarget 6, 16735–16745 (2015).

Chi, M. S. et al. Double autophagy modulators reduce 2-deoxyglucose uptake in sarcoma patients. Oncotarget 6, 29808–29817 (2015).

Bilger, A. et al. FET-PET-based reirradiation and chloroquine in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: first tolerability and feasibility results. Strahlenther. Onkol. 190, 957–961 (2014).

Goldberg, S. B. et al. A phase I study of erlotinib and hydroxychloroquine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac Oncol. 7, 1602–1608 (2012).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01594242?term=NCT01594242&rank=1 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01874548?term=NCT01874548&rank=1 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01506973?term=NCT01506973&rank=1(2017).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01978184?term=NCT01978184&rank=1 (2015).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01128296?term=NCT01128296&rank=1 (2015).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01897116?term=NCT01897116&rank=1 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors' laboratories is supported by an elope, Inc. St Baldrick's Foundation Scholar Award, NIH/NCI (K08CA193982), and the Morgan Adams Foundation (J.M.L.). T32 CA190216-1 A1 (C.G.T.) and NIH CA150925, CA190170 and CA197887 (A.T.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Glossary

- Autophagic flux

-

A measure of the amount of cellular cargo and the rate at which it is degraded by the autophagy pathway.

- Nutraceuticals

-

Food with a medicinal benefit.

- Pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic parameters

-

(PK–PD parameters). The study of the time course of metabolism (PK) and the biochemical and physiological effects (PD) of a drug.

- Maximum tolerated dose

-

(MTD). The highest dose of a treatment that is effective and that does not cause unacceptable side effects.

- Myelosuppression

-

A decrease in bone marrow activity that results in fewer red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levy, J., Towers, C. & Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 17, 528–542 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.53

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.53

This article is cited by

Crosstalk between metabolism and cell death in tumorigenesis

Molecular Cancer (2024)

Selective autophagy in cancer: mechanisms, therapeutic implications, and future perspectives

Molecular Cancer (2024)

AAA237, an SKP2 inhibitor, suppresses glioblastoma by inducing BNIP3-dependent autophagy through the mTOR pathway

Cancer Cell International (2024)

Icariin exerts anti-tumor activity by inducing autophagy via AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway in triple-negative breast cancer

Cancer Cell International (2024)

Unveiling the mechanisms and challenges of cancer drug resistance

Cell Communication and Signaling (2024)