The radical Reformation

in 16th century

The expression “radical Reformation” was given to a complex and multifarious movement that found the lutherans and the swiss Reformers not daring enough, and considered that the Reformation had only gone half-way.

The origin of the movement

The so-called “radical” Reformation appeared in two different places, namely in Germany in Luther’s wake, and in Switzerland in Zwingli’s wake, but against both.

In Germany, Thomas Müntzer, a former priest who had become a pastor, thought that Luther was too restrained and had not gone the whole way, but stopped in the middle. Luther reformed the Church, but Müntzer thought society should be reformed too, made fairer by abolishing the privileges of the nobility, by giving rights to the people, by distributing wealth to all.

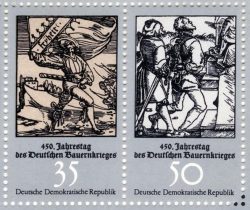

Whereas Luther called for submission to the social and political authorities, Müntzer preached revolt. The peasants, especially poor and exploited, heard him and rebelled, but were crushed at the battle of Frankhausen in 1525. Müntzer was made prisoner, tortured and then killed. Luther asked the nobility to pitilessly repress the peasants.

Between 1521 and 1524 in Zurich, Switzerland, a few inhabitants considered that Zwingli was too slow. They reproached him for his progressive reformation step by step, instead of a clear-cut break. For instance, when Zwingli was finally convinced that the mass was non-biblical, it took him three years to abolish it in favour of the reformed service. Zwingli’s purpose was pastoral and pedagogical, so he took time to explain and convince. He only made changes when he believed the people were ready for them. But some of his collaborators, gathered around the radical Grebel, wished things to be clearer, and to confront each individual with his choice and his own decisions.

The anabaptists

Müntzer and Grebel both refused to christen babies. Adults alone should be baptised after they have been converted through a personal spiritual experience. Grebel considered the baptism of children null and void. They were called anabaptists because they baptized again those who had been baptised at birth.That was the break-away point with Zwingli.

Whereas Müntzer advocated an armed revolt, Grebel chose pacifism, because a Christian should not use violence, even for a just cause.

The radicals were heavily persecuted, they were massacred in Germany, in Zurich they were drowned in the lake, and sardonically sentenced with the words : “they who sinned by the water, and shall perish by the water”. In 1523 a synod took place in Schleitheim and was called “synod of martyrs”, because almost all the participants were executed for religious reasons.

The various movements

After Thomas Münster’s defeat and the dispersal of Grebel’s friends, the radical reformation went on through small clandestine groups of which little is known. After a bloody period in the town of Münster (Wesphaly) in 1534-35 (the theme of Sartre’s play Le Diable et le Bon Dieu (The Devil and the Good God), they objected to violence and definitely became pacifists.

Three tendencies often combine in those groups:

- Firstly, Antipedobaptism, or refusal to christen children. The lutherans and reformed wanted a church for the people, not separated from the city. The radicals wanted a church for the “pure”. The worshippers should break away from the majority and from the earthly city, which justified the refusal of the baptism of children. After 1535, the main leader of this movement was Dutch – Menno Simon after whom the Mennonites were named. This trend can still be seen in the present Baptist movement.

- Secondly Illuminism or spiritualism proclaimed that the Holy Spirit spoke directly to the believers, teaching them the doctrines, dictating their behaviour through revelations. In this movement some people pretended they were prophets. Illuminists can be considered the spiritual ancestors of the present-day Pentecostal and Charismatics.

- Thirdly, Unitarism or Anti-trinitarism refused the dogma of trinity considered non-biblical. It sought to reconcile revelation and reason, because one and the other were God given. Fausto Socin, an Italian who had settled in Poland, and died in 1604, was its leader. This trend is present in liberal Protestantism and Unitarism.

The radical reformation did not want to keep anything of the catholic Church. Its purpose was only to follow the apostolic model, to recreate the Church of the New Testament by eradicating the heritage of past centuries. The Lutherans and Reformed thought that anything not forbidden in the Bible was allowed. For the radicals, what was not expressly called for in the Bible was forbidden.

The radical Reformation never succeeded in winning over a territory, nor in having a geographical centre, though this almost happened in Poland. It became quite influential in Transylvania (nowadays Romania), but never ruled a region. The radical Reformation was composed of small, discreet, and often influential groups lead by marginal intellectuals who wandered all over Europe – i.e. Servet, Marpeck, Schlatter, Joris, and the best known Menno Simon and Fausto Socin- rather than by university teachers, as was the case with the magisterial reformation. It mainly concerned artisans -nowadays called technicians. It was terribly persecuted as much by the lutherans and the reformed as by the catholics.

Bibliography

- Books

- BAECHER Claude, Michael Sattler, la naissance d’Église de professants, Excelsis, 2002

- Collectif, Miroir des martyrs (anabaptistes), Excelsis, 2003

Associated notes

-

Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531)

Zwingli, a pastor and theologian, based the Reformation on Bible study. In his opinion the Reformation comprised fighting social injustice. -

Several models of Reformation

In itself, the Reformation appeared everywhere. Everywhere, in France, in Switzerland, it was indigenous, a fruit of the land and of various circumstances that, nevertheless, produced similar fruit. -

The Calvinist Reformation in 16th century

The Reformation later known as Calvinist movement was launched by several reformers and spread to many parts of Europe, from Zurich and Geneva. -

The Catholic Reformation or Counter-Reformation in 16th century

The council of Trent (1545-1563) was a turning point in the history of Catholicism when dogma and disciplinary reforms were passed.