Abstract

The composition of the gut microbiota is in constant flow under the influence of factors such as the diet, ingested drugs, the intestinal mucosa, the immune system, and the microbiota itself. Natural variations in the gut microbiota can deteriorate to a state of dysbiosis when stress conditions rapidly decrease microbial diversity and promote the expansion of specific bacterial taxa. The mechanisms underlying intestinal dysbiosis often remain unclear given that combinations of natural variations and stress factors mediate cascades of destabilizing events. Oxidative stress, bacteriophages induction and the secretion of bacterial toxins can trigger rapid shifts among intestinal microbial groups thereby yielding dysbiosis. A multitude of diseases including inflammatory bowel diseases but also metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes type II are associated with intestinal dysbiosis. The characterization of the changes leading to intestinal dysbiosis and the identification of the microbial taxa contributing to pathological effects are essential prerequisites to better understand the impact of the microbiota on health and disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sonnenburg JL, Backhed F (2016) Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535(7610):56–64

LeBlanc JG et al (2013) Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: a gut microbiota perspective. Curr Opin Biotechnol 24(2):160–168

Honda K, Littman DR (2016) The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature 535(7610):75–84

Thaiss CA et al (2016) The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature 535(7610):65–74

Mayer EA, Tillisch K, Gupta A (2015) Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. J Clin Invest 125(3):926–938

Zitvogel L et al (2015) Cancer and the gut microbiota: an unexpected link. Sci Transl Med 7(271):271ps1

Arumugam M et al (2011) Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 473(7346):174–180

Walker AW et al (2011) High-throughput clone library analysis of the mucosa-associated microbiota reveals dysbiosis and differences between inflamed and non-inflamed regions of the intestine in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Microbiol 11:7

Lupp C et al (2007) Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe 2(2):119–129

Wlodarska M, Kostic AD, Xavier RJ (2015) An integrative view of microbiome–host interactions in inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Host Microbe 17(5):577–591

Gerard P (2016) Gut microbiota and obesity. Cell Mol Life Sci 73(1):147–162

Knip M, Siljander H (2016) The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12(3):154–167

Tremlett H et al (2017) The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: a review. Ann Neurol 81(3):369–382

Neu J, Walker WA (2011) Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med 364(3):255–264

Schwabe RF, Jobin C (2013) The microbiome and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 13(11):800–812

Seekatz AM, Young VB (2014) Clostridium difficile and the microbiota. J Clin Invest 124(10):4182–4189

Cox, MJ, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF (2013) Sequencing the human microbiome in health and disease. Hum Mol Genet 22(R1):R88–R94

Turnbaugh PJ et al (2006) An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444(7122):1027–1031

Gregory JC et al (2015) Transmission of atherosclerosis susceptibility with gut microbial transplantation. J Biol Chem 290(9):5647–5660

Rakoff-Nahoum S, Foster KR, Comstock LE (2016) The evolution of cooperation within the gut microbiota. Nature 533(7602):255–259

Chow J, Tang H, Mazmanian SK (2011) Pathobionts of the gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol 23(4):473–480

Tenaillon O et al (2010) The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol 8(3):207–217

Stecher B et al (2007) Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol 5(10):2177–2189

Chevalier C et al (2015) Gut microbiota orchestrates energy homeostasis during cold. Cell 163(6):1360–1374

Li L, Zhao X (2015) Comparative analyses of fecal microbiota in Tibetan and Chinese Han living at low or high altitude by barcoded 454 pyrosequencing. Sci Rep 5:14682

Ritchie LE et al (2015) Space environmental factor impacts upon murine colon microbiota and mucosal homeostasis. PLoS One 10(6):e0125792

Scott KP et al (2013) The influence of diet on the gut microbiota. Pharmacol Res 69(1):52–60

Demehri FR, Barrett M, Teitelbaum DH (2015) Changes to the intestinal microbiome with parenteral nutrition: review of a murine model and potential clinical implications. Nutr Clin Pract 30(6):798–806

Le Chatelier E et al (2013) Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 500(7464):541–546

Ley RE et al (2005) Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(31):11070–11075

Ley RE et al (2006) Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444(7122):1022–1023

Kasai C et al (2015) Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterol 15:100

Caricilli AM et al (2011) Gut microbiota is a key modulator of insulin resistance in TLR 2 knockout mice. PLoS Biol 9(12):e1001212

Cani PD et al (2007) Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56(7):1761–1772

Festi D et al (2014) Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 20(43):16079–16094

Martinez-Medina M et al (2014) Western diet induces dysbiosis with increased E. coli in CEABAC10 mice, alters host barrier function favouring AIEC colonisation. Gut 63(1):116–124

Wu GD et al (2011) Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334(6052):105–108

Shankar V et al (2017) Differences in gut metabolites and microbial composition and functions between Egyptian and U.S. children are consistent with their diets. mSystems 2(1)

Russell WR et al (2011) High-protein, reduced-carbohydrate weight-loss diets promote metabolite profiles likely to be detrimental to colonic health. Am J Clin Nutr 93(5):1062–1072

Liu X et al (2014) High-protein diet modifies colonic microbiota and luminal environment but not colonocyte metabolism in the rat model: the increased luminal bulk connection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307(4):G459–G470

Magee EA et al (2000) Contribution of dietary protein to sulfide production in the large intestine: an in vitro and a controlled feeding study in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 72(6):1488–1494

Alemany M (2012) The problem of nitrogen disposal in the obese. Nutr Res Rev 25(1):18–28

Zahedi Asl S, Ghasemi A, Azizi F (2008) Serum nitric oxide metabolites in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Clin Biochem 41(16–17):1342–1347

Dykhuizen RS et al (1996) Antimicrobial effect of acidified nitrite on gut pathogens: importance of dietary nitrate in host defense. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40(6):1422–1425

Zhang C et al (2012) Structural resilience of the gut microbiota in adult mice under high-fat dietary perturbations. ISME J 6(10):1848–1857

Caesar R et al (2015) Crosstalk between gut microbiota and dietary lipids aggravates WAT inflammation through TLR signaling. Cell Metab 22(4):658–668

Bell DS (2015) Changes seen in gut bacteria content and distribution with obesity: causation or association? Postgrad Med 127(8):863–868

Islam KB et al (2011) Bile acid is a host factor that regulates the composition of the cecal microbiota in rats. Gastroenterology 141(5):1773–1781

Murakami Y, Tanabe S, Suzuki T (2016) High-fat diet-induced intestinal hyperpermeability is associated with increased bile acids in the large intestine of mice. J Food Sci 81(1):H216–H222

Thomas C et al (2008) Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7(8):678–693

Thomas C, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K (2008) Bile acids and the membrane bile acid receptor TGR5-connecting nutrition and metabolism. Thyroid 18(2):167–174

Watanabe M et al (2006) Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 439(7075):484–489

Fiorucci S, Distrutti E (2015) Bile acid-activated receptors, intestinal microbiota, and the treatment of metabolic disorders. Trends Mol Med 21(11):702–714

De Filippo C et al (2010) Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(33):14691–14696

DiBaise JK et al (2008) Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity. Mayo Clin Proc 83(4):460–469

Backhed F et al (2004) The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(44):15718–15723

Sanders FW, Griffin JL (2016) De novo lipogenesis in the liver in health and disease: more than just a shunting yard for glucose. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 91(2):452–468

Guarner F, Malagelada JR (2003) Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 361(9356):512–519

Arslan N (2014) Obesity, fatty liver disease and intestinal microbiota. World J Gastroenterol 20(44):16452–16463

Le Poul E et al (2003) Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem 278(28):25481–25489

Brown AJ et al (2003) The Orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem 278(13):11312–11319

Ang Z, Ding JL (2016) GPR41 and GPR43 in obesity and inflammation—protective or causative? Front Immunol 7:28

Zaibi MS et al (2010) Roles of GPR41 and GPR43 in leptin secretory responses of murine adipocytes to short chain fatty acids. FEBS Lett 584(11):2381–2386

Xiong Y et al (2004) Short-chain fatty acids stimulate leptin production in adipocytes through the G protein-coupled receptor GPR41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(4):1045–1050

Brandsma E et al (2015) The immunity-diet-microbiota axis in the development of metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Lipidol 26(2):73–81

Cummings JH et al (1987) Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28(10):1221–1227

Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT (2003) Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc Nutr Soc 62(1):67–72

Walker AW et al (2011) Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J 5(2):220–230

Cani PD et al (2009) Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 58(8):1091–1103

Everard A et al (2011) Responses of gut microbiota and glucose and lipid metabolism to prebiotics in genetic obese and diet-induced leptin-resistant mice. Diabetes 60(11):2775–2786

Parnell JA, Reimer RA (2012) Prebiotic fibres dose-dependently increase satiety hormones and alter Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes in lean and obese JCR:LA-cp rats. Br J Nutr 107(4):601–613

Backhed F et al (2007) Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(3):979–984

Aronsson L et al (2010) Decreased fat storage by Lactobacillus paracasei is associated with increased levels of angiopoietin-like 4 protein (ANGPTL4). PLoS One 5(9)

Cani PD, Everard A (2014) Akkermansia muciniphila: a novel target controlling obesity, type 2 diabetes and inflammation? Med Sci (Paris) 30(2):125–127

Everard A et al (2013) Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(22):9066–9071

Malik A et al (2016) IL-33 regulates the IgA-microbiota axis to restrain IL-1alpha-dependent colitis and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest 126(12):4469–4481

Kang CS et al (2013) Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially Akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. PLoS One 8(10):e76520

Gilbert HJ (2010) The biochemistry and structural biology of plant cell wall deconstruction. Plant Physiol 153(2):444–455

Fabich AJ et al (2008) Comparison of carbon nutrition for pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun 76(3):1143–1152

Pacheco AR et al (2012) Fucose sensing regulates bacterial intestinal colonization. Nature 492(7427):113–117

Pickard JM et al (2014) Rapid fucosylation of intestinal epithelium sustains host-commensal symbiosis in sickness. Nature 514(7524):638–641

Vimr ER et al (2004) Diversity of microbial sialic acid metabolism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68(1):132–153

Marcobal A et al (2011) Bacteroides in the infant gut consume milk oligosaccharides via mucus-utilization pathways. Cell Host Microbe 10(5):507–514

Ng KM et al (2013) Microbiota-liberated host sugars facilitate post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens. Nature 502(7469):96–99

Huang YL et al (2015) Sialic acid catabolism drives intestinal inflammation and microbial dysbiosis in mice. Nat Commun 6:8141. doi:10.1038/ncomms9141

Rogers MA, Aronoff DM (2016) The influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the gut microbiome. Clin Microbiol Infect 178(2):e1–e9

Freedberg DE et al (2015) Proton pump inhibitors alter specific taxa in the human gastrointestinal microbiome: a crossover trial. Gastroenterology 149(4):883–885

Tsai CF et al (2017) Proton pump inhibitors increase risk for hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis in a population study. Gastroenterology 152(1):134–141

Forslund K et al (2015) Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature 528(7581):262–266

Korpela K et al (2016) Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat Commun 7:10410

Dethlefsen L, Relman DA (2011) Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 Suppl 1:4554–4561

Furuya-Kanamori L et al (2015) Comorbidities, exposure to medications, and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 36(2):132–141

Galdston I (1944) Eubiotic medicine. Science 100(2587):76

Guslandi M (2011) Rifaximin in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 17(42):4643–4646

Pimentel M et al (2011) Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med 364(1):22–32

Swanson HI (2015) Drug metabolism by the host and gut microbiota: a partnership or rivalry? Drug Metab Dispos 43(10):1499–1504

Aura AM et al (2011) Drug metabolome of the simvastatin formed by human intestinal microbiota in vitro. Mol Biosyst 7(2):437–446

Yadav V et al (2013) Colonic bacterial metabolism of corticosteroids. Int J Pharm 457(1):268–274

Wallace BD et al (2010) Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science 330(6005):831–835

Lim YJ, Yang CH (2012) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy. Clin Endosc 45(2):138–144

Robbe C et al (2003) Evidence of regio-specific glycosylation in human intestinal mucins: presence of an acidic gradient along the intestinal tract. J Biol Chem 278(47):46337–46348

Corfield AP (2015) Mucins: a biologically relevant glycan barrier in mucosal protection. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850(1):236–252

Ahn DH et al (2005) TNF-alpha activates MUC2 transcription via NF-kappaB but inhibits via JNK activation. Cell Physiol Biochem 15(1–4):29–40

Hokari R et al (2005) Vasoactive intestinal peptide upregulates MUC2 intestinal mucin via CREB/ATF1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289(5):G949–G959

Larsson JM et al (2011) Altered O-glycosylation profile of MUC2 mucin occurs in active ulcerative colitis and is associated with increased inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17(11):2299–2307

Goto Y et al (2014) Innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal epithelial cell glycosylation. Science 345(6202):1254009

Png CW et al (2010) Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria. Am J Gastroenterol 105(11):2420–2428

Sela DA et al (2008) The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(48):18964–18969

Derrien M et al (2004) Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54(Pt 5):1469–1476

Martens EC, Chiang HC, Gordon JI (2008) Mucosal glycan foraging enhances fitness and transmission of a saccharolytic human gut bacterial symbiont. Cell Host Microbe 4(5):447–457

Etzold S, Juge N (2014) Structural insights into bacterial recognition of intestinal mucins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 28C:23–31

Mahdavi J et al (2014) A novel O-linked glycan modulates Campylobacter jejuni major outer membrane protein-mediated adhesion to human histo-blood group antigens and chicken colonization. Open Biol 4:130202

Ruiz-Palacios GM et al (2003) Campylobacter jejuni binds intestinal H(O) antigen (Fuc alpha 1, 2Gal beta 1, 4GlcNAc), and fucosyloligosaccharides of human milk inhibit its binding and infection. J Biol Chem 278(16):14112–14120

Kyogashima M, Ginsburg V, Krivan HC (1989) Escherichia coli K99 binds to N-glycolylsialoparagloboside and N-glycolyl-GM3 found in piglet small intestine. Arch Biochem Biophys 270(1):391–397

Byres E et al (2008) Incorporation of a non-human glycan mediates human susceptibility to a bacterial toxin. Nature 456(7222):648–652

Tangvoranuntakul P et al (2003) Human uptake and incorporation of an immunogenic nonhuman dietary sialic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100(21):12045–12050

Barr JJ et al (2013) Bacteriophage adhering to mucus provide a non-host-derived immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(26):10771–10776

McGovern DP et al (2010) Fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) non-secretor status is associated with Crohn’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 19(17):3468–3476

Johansson ME et al (2015) Normalization of host intestinal mucus layers requires long-term microbial colonization. Cell Host Microbe 18(5):582–592

Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ (2010) Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol 10(3):159–169

Suzuki K et al (2004) Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(7):1981–1986

Elinav E et al (2011) NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell 145(5):745–757

Wlodarska M et al (2014) NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell 156(5):1045–1059

Nowarski R et al (2015) Epithelial IL-18 equilibrium controls barrier function in colitis. Cell 163(6):1444–1456

Gersemann M et al (2009) Differences in goblet cell differentiation between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Differentiation 77(1):84–94

Huber S et al (2012) IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature 491(7423):259–263

Zheng Y et al (2008) Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med 14(3):282–289

McSorley SJ et al (2002) Bacterial flagellin is an effective adjuvant for CD4+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol 169(7):3914–3919

McDermott PF et al (2000) High-affinity interaction between gram-negative flagellin and a cell surface polypeptide results in human monocyte activation. Infect Immun 68(10):5525–5529

Van Maele L et al (2010) TLR5 signaling stimulates the innate production of IL-17 and IL-22 by CD3(neg)CD127+ immune cells in spleen and mucosa. J Immunol 185(2):1177–1185

Vijay-Kumar M et al (2010) Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science 328(5975):228–231

Vijay-Kumar M et al (2007) Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest 117(12):3909–3921

Carvalho FA et al (2012) Transient inability to manage proteobacteria promotes chronic gut inflammation in TLR5-deficient mice. Cell Host Microbe 12(2):139–152

Kobayashi KS et al (2005) Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science 307(5710):731–734

Petnicki-Ocwieja T et al (2009) Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(37):15813–15818

Salzman NH et al (2010) Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol 11(1):76–83

Ogura Y et al (2001) A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 411(6837):603–606

Wehkamp J et al (2005) Reduced Paneth cell alpha-defensins in ileal Crohn’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(50):18129–18134

Davis CP, Savage DC (1974) Habitat, succession, attachment, and morphology of segmented, filamentous microbes indigenous to the murine gastrointestinal tract. Infect Immun 10(4):948–956

Kumar P et al (2016) Intestinal interleukin-17 receptor signaling mediates reciprocal control of the gut microbiota and autoimmune inflammation. Immunity 44(3):659–671

Gaboriau-Routhiau V et al (2009) The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity 31(4):677–689

Sakaguchi S et al (2008) Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 133(5):775–787

Arthur JC et al (2012) Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 338(6103):120–123

Wohlgemuth S et al (2009) Reduced microbial diversity and high numbers of one single Escherichia coli strain in the intestine of colitic mice. Environ Microbiol 11(6):1562–1571

Di Giacinto C et al (2005) Probiotics ameliorate recurrent Th1-mediated murine colitis by inducing IL-10 and IL-10-dependent TGF-beta-bearing regulatory cells. J Immunol 174(6):3237–3246

Sokol H et al (2008) Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(43):16731–16736

Kashiwagi I et al (2015) Smad2 and Smad3 inversely regulate TGF-beta autoinduction in clostridium butyricum-activated dendritic cells. Immunity 43(1):65–79

Ihara S et al (2016) TGF-beta signaling in dendritic cells governs colonic homeostasis by controlling epithelial differentiation and the luminal microbiota. J Immunol 196(11):4603–4613

Sato J et al (2014) Gut dysbiosis and detection of “live gut bacteria” in blood of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 37(8):2343–2350

Mazmanian SK, Kasper DL (2006) The love-hate relationship between bacterial polysaccharides and the host immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 6(11):849–858

Ivanov II et al (2009) Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 139(3):485–498

Karczewski J et al (2014) The effects of the microbiota on the host immune system. Autoimmunity 47(8):494–504

Wen L et al (2008) Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature 455(7216):1109–1113

Burrows MP et al (2015) Microbiota regulates type 1 diabetes through Toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(32):9973–9977

Larsson E et al (2012) Analysis of gut microbial regulation of host gene expression along the length of the gut and regulation of gut microbial ecology through MyD88. Gut 61(8):1124–1131

Kriegel MA et al (2011) Naturally transmitted segmented filamentous bacteria segregate with diabetes protection in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(28):11548–11553

Clarke TB et al (2010) Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med 16(2):228–231

Ganal SC et al (2012) Priming of natural killer cells by nonmucosal mononuclear phagocytes requires instructive signals from commensal microbiota. Immunity 37(1):171–186

Khosravi A et al (2014) Gut microbiota promote hematopoiesis to control bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe 15(3):374–381

Hill DA et al (2012) Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat Med 18(4):538–546

Zeissig S, Blumberg RS (2014) Life at the beginning: perturbation of the microbiota by antibiotics in early life and its role in health and disease. Nat Immunol 15(4):307–310

Ng SC et al (2013) Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 62(4):630–649

Murk W, Risnes KR, Bracken MB (2011) Prenatal or early-life exposure to antibiotics and risk of childhood asthma: a systematic review. Pediatrics 127(6):1125–1138

Flohr C, Pascoe D, Williams HC (2005) Atopic dermatitis and the ‘hygiene hypothesis’: too clean to be true? Br J Dermatol 152(2):202–216

Winter SE et al (2010) Gut inflammation provides a respiratory electron acceptor for Salmonella. Nature 467(7314):426–429

Scanlan PD, Shanahan F, Marchesi JR (2009) Culture-independent analysis of desulfovibrios in the human distal colon of healthy, colorectal cancer and polypectomized individuals. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 69(2):213–221

Hensel M et al (1999) The genetic basis of tetrathionate respiration in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 32(2):275–287

Pryor WA, Squadrito GL (1995) The chemistry of peroxynitrite: a product from the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide. Am J Physiol 268(5 Pt 1):L699–L722

Winter SE et al (2013) Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science 339(6120):708–711

Lopez CA et al (2012) Phage-mediated acquisition of a type III secreted effector protein boosts growth of salmonella by nitrate respiration. MBio 3(3)

Manrique P et al (2016) Healthy human gut phageome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(37):10400–10405

Minot S et al (2011) The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res 21(10):1616–1625

Stern A et al (2012) CRISPR targeting reveals a reservoir of common phages associated with the human gut microbiome. Genome Res 22(10):1985–1994

Norman JM et al (2015) Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 160(3):447–460

Zhang X et al (2000) Quinolone antibiotics induce Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages, toxin production, and death in mice. J Infect Dis 181(2):664–670

Fraser JS, Maxwell KL, Davidson AR (2007) Immunoglobulin-like domains on bacteriophage: weapons of modest damage? Curr Opin Microbiol 10(4):382–387

Arike L, Hansson GC (2016) The densely O-glycosylated MUC2 mucin protects the intestine and provides food for the commensal bacteria. J Mol Biol 428(16):3221–3229

Kim YS, Ho SB (2010) Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 12(5):319–330

Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP (2005) Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat Rev Microbiol 3(10):777–788

Rebuffat S (2012) Microcins in action: amazing defence strategies of Enterobacteria. Biochem Soc Trans 40(6):1456–1462

Ghazaryan L et al (2014) The role of stress in colicin regulation. Arch Microbiol 196(11):753–764

Patzer SI et al (2003) The colicin G, H and X determinants encode microcins M and H47, which might utilize the catecholate siderophore receptors FepA, Cir, Fiu and IroN. Microbiology 149(Pt 9):2557–2570

Sassone-Corsi M et al (2016) Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut. Nature 540(7632):280–283

Losurdo G et al (2015) Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in Ulcerative colitis treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 24(4):499–505

Scaldaferri F et al (2016) Role and mechanisms of action of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in the maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis patients: an update. World J Gastroenterol 22(24):5505–5511

Kommineni S et al (2015) Bacteriocin production augments niche competition by enterococci in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract. Nature 526(7575):719–722

Gebhart D et al (2015) A modified R-type bacteriocin specifically targeting Clostridium difficile prevents colonization of mice without affecting gut microbiota diversity. MBio 6(2)

Xin B et al (2016) Thusin, a novel two-component lantibiotic with potent antimicrobial activity against several gram-positive pathogens. Front Microbiol 7:1115

Cammarota G et al (2015) The involvement of gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: potential for therapy. Pharmacol Ther 149:191–212

Scott FW et al (2017) Where genes meet environment-integrating the role of gut luminal contents, immunity and pancreas in type 1 diabetes. Transl Res 179:183–198

Losurdo G et al (2016) The interaction between celiac disease and intestinal microbiota. J Clin Gastroenterol 50(Suppl 2):S145–S147

Tang WH, Hazen SL (2014) The contributory role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 124(10):4204–4211

Lucas A, Cole TJ (1990) Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet 336(8730):1519–1523

Gartner LM et al (2005) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 115(2):496–506

Foster JP, Seth R, Cole MJ (2016) Oral immunoglobulin for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm and low birth weight neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD001816

Srinivasjois R, Rao S, Patole S (2013) Prebiotic supplementation in preterm neonates: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Nutr 32(6):958–965

Costeloe K et al (2016) Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001 in very preterm infants: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 387(10019):649–660

Kuper H, Adami HO, Trichopoulos D (2000) Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J Intern Med 248(3):171–183

Irrazabal T et al (2014) The multifaceted role of the intestinal microbiota in colon cancer. Mol Cell 54(2):309–320

Franco AT et al (2005) Activation of beta-catenin by carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(30):10646–10651

Wang F et al (2014) Helicobacter pylori infection and normal colorectal mucosa-adenomatous polyp-adenocarcinoma sequence: a meta-analysis of 27 case–control studies. Colorectal Dis 16(4):246–252

Hatakeyama M, Higashi H (2005) Helicobacter pylori CagA: a new paradigm for bacterial carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci 96(12):835–843

Gao Z et al (2015) Microbiota disbiosis is associated with colorectal cancer. Front Microbiol 6:20

Ahn J et al (2013) Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 105(24):1907–1911

Castellarin M et al (2012) Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 22(2):299–306

Han YW et al (2005) Identification and characterization of a novel adhesin unique to oral fusobacteria. J Bacteriol 187(15):5330–5340

Fardini Y et al (2011) Fusobacterium nucleatum adhesin FadA binds vascular endothelial cadherin and alters endothelial integrity. Mol Microbiol 82(6):1468–1480

Rubinstein MR et al (2013) Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/beta-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 14(2):195–206

Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R (2007) Regulation of spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis through the adaptor protein MyD88. Science 317(5834):124–127

Salcedo R et al (2010) MyD88-mediated signaling prevents development of adenocarcinomas of the colon: role of interleukin 18. J Exp Med 207(8):1625–1636

Hu B et al (2010) Inflammation-induced tumorigenesis in the colon is regulated by caspase-1 and NLRC4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(50):21635–21640

Zaki MH et al (2010) IL-18 production downstream of the Nlrp3 inflammasome confers protection against colorectal tumor formation. J Immunol 185(8):4912–4920

Chen GY et al (2011) A functional role for Nlrp6 in intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Immunol 186(12):7187–7194

Saleh M, Trinchieri G (2011) Innate immune mechanisms of colitis and colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 11(1):9–20

Fukata M et al (2007) Toll-like receptor-4 promotes the development of colitis-associated colorectal tumors. Gastroenterology 133(6):1869–1881

Wang EL et al (2010) High expression of Toll-like receptor 4/myeloid differentiation factor 88 signals correlates with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 102(5):908–915

Doan HQ et al (2009) Toll-like receptor 4 activation increases Akt phosphorylation in colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res 29(7):2473–2478

Fukata M et al (2006) Cox-2 is regulated by Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) signaling: role in proliferation and apoptosis in the intestine. Gastroenterology 131(3):862–877

Fukata M, Abreu MT (2007) TLR4 signalling in the intestine in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans 35(Pt 6):1473–1478

Yu LC et al (2012) Host-microbial interactions and regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier function: from physiology to pathology. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 3(1):27–43

Calle EE, Kaaks R (2004) Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 4(8):579–591

Cario E, Podolsky DK (2000) Differential alteration in intestinal epithelial cell expression of toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Infect Immun 68(12):7010–7017

Bernstein CN et al (2001) Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer 91(4):854–862

Lukas M (2010) Inflammatory bowel disease as a risk factor for colorectal cancer. Dig Dis 28(4–5):619–624

Uronis JM et al (2009) Modulation of the intestinal microbiota alters colitis-associated colorectal cancer susceptibility. PLoS One 4(6):e6026

Azcarate-Peril MA, Sikes M, Bruno-Barcena JM (2011) The intestinal microbiota, gastrointestinal environment and colorectal cancer: a putative role for probiotics in prevention of colorectal cancer? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301(3):G401–G424

Wu S et al (2003) Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces c-Myc expression and cellular proliferation. Gastroenterology 124(2):392–400

Goodwin AC et al (2011) Polyamine catabolism contributes to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced colon tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(37):15354–15359

Cuevas-Ramos G et al (2010) Escherichia coli induces DNA damage in vivo and triggers genomic instability in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(25):11537–11542

Singh N et al (2014) Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity 40(1):128–139

Alasmari F et al (2014) Prevalence and risk factors for asymptomatic Clostridium difficile carriage. Clin Infect Dis 59(2):216–222

Carter GP, Rood JI, Lyras D (2012) The role of toxin A and toxin B in the virulence of Clostridium difficile. Trends Microbiol 20(1):21–29

Kelly CP et al (1994) Neutrophil recruitment in Clostridium difficile toxin A enteritis in the rabbit. J Clin Invest 93(3):1257–1265

Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL (2008) Bile salts and glycine as cogerminants for Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol 190(7):2505–2512

Wilson KH, Perini F (1988) Role of competition for nutrients in suppression of Clostridium difficile by the colonic microflora. Infect Immun 56(10):2610–2614

Theriot CM et al (2014) Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Commun 5:3114

Buffie CG et al (2012) Profound alterations of intestinal microbiota following a single dose of clindamycin results in sustained susceptibility to Clostridium difficile-induced colitis. Infect Immun 80(1):62–73

Lawley TD et al (2012) Targeted restoration of the intestinal microbiota with a simple, defined bacteriotherapy resolves relapsing Clostridium difficile disease in mice. PLoS Pathog 8(10):e1002995

Reeves AE et al (2011) The interplay between microbiome dynamics and pathogen dynamics in a murine model of Clostridium difficile infection. Gut Microbes 2(3):145–158

Hopkins MJ, Macfarlane GT (2002) Changes in predominant bacterial populations in human faeces with age and with Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Microbiol 51(5):448–454

Rea MC et al (2012) Clostridium difficile carriage in elderly subjects and associated changes in the intestinal microbiota. J Clin Microbiol 50(3):867–875

van Nood E et al (2013) Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 368(5):407–415

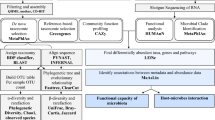

Garza DR, Dutilh BE (2015) From cultured to uncultured genome sequences: metagenomics and modeling microbial ecosystems. Cell Mol Life Sci 72(22):4287–4308

Thiele I, Palsson BO (2010) A protocol for generating a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. Nat Protoc 5(1):93–121

Chen J et al (2007) Improving metabolic flux estimation via evolutionary optimization for convex solution space. Bioinformatics 23(9):1115–1123

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation Grant CRSII3_154488/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weiss, G.A., Hennet, T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 2959–2977 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-017-2509-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-017-2509-x