The laws of football now stretch to precisely 140 pages, but our comprehension of them could probably be covered in 140 characters. Football has always been a simple, intuitively understood game, with exceptions to that few and far between.

Two spring to mind. The first is the offside law, the bane of pepper pots up and down the land. Though the ever-changing interpretation of offside has caused much confusion, it's actually a pretty straightforward concept and one that is, at least, exactly defined. The same is not true when it comes to volleys. Depending which watercooler you lurk by, you will find an entirely different comprehension of what constitutes a volley.

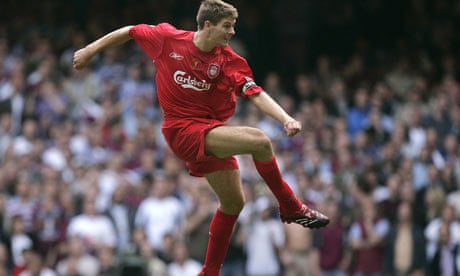

By way of example, Steven Gerrard's winner at Bolton on Saturday was widely described as a volley, yet the ball bounced before he adjusted his body to lash it into the net. As such, can it really be called a volley? There is scarcely anything resembling consensus on this issue. Take a not dissimilar goal from Gerrard in the 2006 FA Cup final, which was described by both Wikipedia and this site as a volley even though it bounced twice before he thrashed it into the net.

The confusion is all the more inexplicable given that we all grew up playing a game in which a volley was precisely characterised: Heads and Volleys. In that, if the ball bounced it was not a volley. Simple. Yet many now think they know different. Are you really smarter than your 10-year-old self?

In the spirit of this, and in view of our commitment to tackle the really big issues, we have attempted to split this type of shot into four sub-genres.

1) A volley

When the ball has not bounced since being touched by the previous player. Obvious examples include Zinedine Zidane's European Cup-winning goal in 2002 and Marco van Basten's miraculous finish in the European Championship final of 1988. But it also includes goals where the attacker has had more than one touch, provided the ball does not hit the floor (see No4), such as this outrageous finish for Swindon by Simon Cox.

2) A half-volley

Many football fans say a half-volley is a shot struck when the ball has bounced once, but in tennis and in cricket there is a different – and surely correct – understanding of the term. A half-volley is hit at precisely the moment that the ball bounces or a split-second after, as with this effort from David Ginola or umpteen strikes from the king of the half-volley, Matthew Le Tissier (here we have exhibits A, B, C and D). With half-volleys it shouldn't matter whether the ball has bounced before it is then struck on the bounce, as with this famous half-volley from Gerrard or this deranged masterpiece from Tony Yeboah; the only defining characteristic is the point at which contact is made, not what has gone before.

3) A bouncing ball

Examples including that Gerrard goal in the 2006 FA Cup final, and Mark Hughes's famous scissor-smash against Spain. And although "struck a bouncing ball into the top corner" sounds nowhere near as exciting as "volleyed into the top corner", these surely aren't volleys. After all, they would not have counted in Heads and Volleys. In a sense that is a little harsh on Hughes, because his was a harder skill than most, but to call it a volley is as illogical as counting shots that hit the woodwork as shots on target. But this type of goal deserves a better name. A bolley? Oh.

4) A make-your-own volley

These are goals where the player manufactures the volley himself, having received either a flat pass or a bouncing one. The primest cuts are probably Paul Gascoigne against Scotland and Thierry Henry against Manchester United. This in no way reduces the majesty of such goals – Henry's in particular is terrifyingly good – but they are not volleys in the truest sense, because the ball is so much easier to strike and control. It's basic physics. But this type of goal also needs a name. A molley? Oh.

At least we now know what constitutes a volley. It's simple. Right?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion