When in the course of human events it becomes necessary to visit a tiny records office in southern England because it claims to have a copy of the Declaration of Independence, a decent respect for history requires investigation.

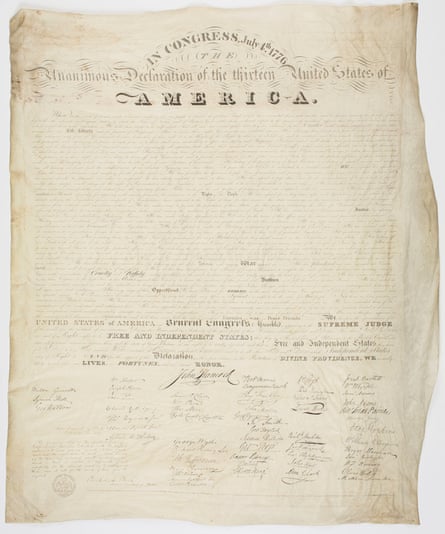

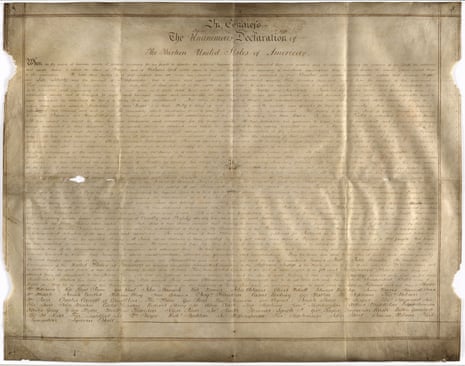

On Friday two Harvard University researchers announced they had found a parchment copy of the declaration, only the second parchment manuscript copy known to exist besides the one kept in the National Archives in Washington DC. Professor Danielle Allen and researcher Emily Sneff presented their findings on the document, known as “The Sussex Declaration”, at a conference at Yale on Friday, and published initial research online.

Sneff found her first clue of the manuscript in August 2015, while compiling records for a university database. “I was just looking for copies of the Declaration of Independence in British archives,” Sneff told the Guardian.

But the listing, for the West Sussex record office, struck Sneff as odd because it mentioned parchment, a material suggesting a document made for a special occasion and not simply a broadside copy.

“I reached out to them a bit skeptically,” Sneff said. “The description was a little vague but once we saw an image and talked to a conservator we started to get excited.”

Before Sneff asked, the British officials had never taken a close look at the manuscript. They had received it in 1956 from a local man, who worked with a law firm that represented the dukes of Richmond. “The closer we looked at it there were just things that made it a clearly unique and mysterious document,” Sneff said.

Allen and Sneff first tried to deduce when and where the manuscript was made by analyzing handwriting, spelling errors and parchment styles and preparation. They concluded it dated to the 1780s, and was produced in America, most likely in New York or Philadelphia.

Their next question proved more difficult: who was the man behind the parchment? Allen and Sneff believe the leading candidate was James Wilson, a Pennsylvania delegate to the continental congress, one of six men to sign both the declaration and constitution, and, later, one of the original supreme court justices. The researchers argue that Wilson, who argued vociferously for a popularly-elected president and separation of powers, played a more influential role in American history than most historians have recognized.

The clue that led them to Wilson, Sneff said, was a stark anomaly on the manuscript compared to its counterpart in Washington DC and later copies: “The names of the signers are all scrambled.”

Unlike previously known copies of the declaration, which have signatures grouped by states, the Sussex copy has its signatures in a patterned jumble. Sneff and Allen hypothesize that the appearance of randomness was deliberate and symbolic, part of a nationalist argument that the United States was founded by citizens, each created equal, and not by a looser confederation of states.

Wilson drew the researchers’ attention, Sneff said, because he repeatedly “invoked the declaration but with the understanding that the declaration was signed by one community, one group of individuals, that they were not enumerated by states.”

Michael Meranze, a professor of the revolutionary era at the University of California Los Angeles, called the evidence behind the manuscript’s 1780s American origin “very persuasive”, and the Wilson hypothesis “plausible” if uncertain.

“There was a huge debate over the constitution, about whether it was a compact of states or of the people,” he said. “Wilson was very much in favor of a nation that claimed its direct roots on popular sovereignty, even if he was simultaneously an elitist in many ways.”

Meranze added that while he also found it convincing that the signatures were disordered deliberately, he cautioned that it was difficult to argue who did so or why without more evidence. “We tend to forget these documents were contested and put to different uses, and not simply monuments,” he said. “It’s a fascinating discovery.”

Sneff and Allen plan to publish their first paper this year in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, and are still working to find more clues about who had the manuscript created. They also face a third confounding riddle: how did it end up in Chichester?

Copies of the declaration made their way to England in the wake of its original 1776 signing, but the Sussex Declaration was made sometime in the next decade, years when America’s leading statesmen were at odds over a post-war financial crisis, an armed uprising and an uncertain constitution. Somehow the manuscript landed in Britain, possibly in the possession of the dukes of Richmond.

Sneff said she is hoping to gain access to the papers of the dukes to trace the declaration’s history, possibly as far back as Charles Lennox, a contemporary of George III who was called “the radical duke” because he supported American colonists in their rebellion against the king and parliament.

“It would be nice to associate this document with the radical duke,” Sneff said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion