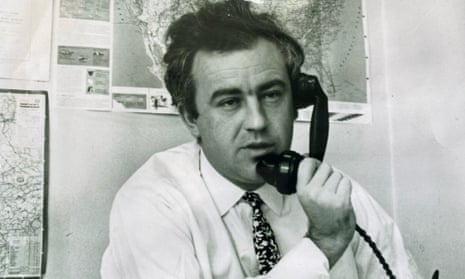

The journalist and historian Godfrey Hodgson, who has died aged 86, was among the most perceptive and industrious observers of his generation, particularly in the field of American society and politics.

His reputation was founded on his landmark study, America in Our Time: From World War II to Nixon (1976), acknowledged by the Cambridge historian Gary Gerstle as “one of the great works of political and social history written in the past half century”. At 600 pages long and in continuous print since its first publication, it was but one item in a prolific output that ran to more than 15 books, extensive university teaching and a lifetime of newspaper and television reporting (as well as numerous Guardian obituaries). As a journalist, Hodgson reckoned he had worked in 48 of the 50 US states.

The central thesis of America in Our Time was that, from the end of the second world war until the mid-1960s, what Hodgson called a “liberal consensus” defined American politics. Conservatives accepted most of the New Deal domestic philosophy espoused by Democrats, and liberals mostly accepted the aggressive foreign policy advocated by Republicans to contain and defeat communism. In theory, the free enterprise system would create abundance at home, leaving America free to civilise the world. The term “liberal consensus” had been used before, but Hodgson was responsible for its entry into the lexicon of American history.

Viewed from an age thrown into turmoil by Donald Trump, this analysis appears sadly optimistic. But it held sway as a key tenet in American academia for many years – a considerable achievement for a British writer in US scholarship. It was a measure of Hodgson’s intellectual honesty that in 2017 he could contribute to a collection of essays, The Liberal Consensus Reconsidered (edited by Robert Mason and Iwan Morgan), reflecting on the inadequacies of his earlier theory and analysing why the period had come to an end; the answers were mainly to do with race, Vietnam and the failure of US capitalism.

Born in Horsham, now in West Sussex, Godfrey returned to the Yorkshire of his family roots at the age of three when his father, Arthur Hodgson, was appointed headteacher of Archbishop Holgate’s grammar school, York. Two tragedies overshadowed his childhood. At the age of two, he contracted osteomyelitis, a bone infection; when he was seven, it became clear that his mother, Jessica (nee Hill), was suffering from untreatable multiple sclerosis.

The former left him with a disfigured right arm and an iron determination to succeed: one of his proudest achievements was later to bowl for the Winchester college first XI. The latter resulted in his being packed off to the Dragon school in Oxford at the age of nine, to shield him from his mother’s illness. He learned of her death in 1947 as a lonely 13-year-old far from home. Perhaps in part to compensate, he poured his considerable intellectual energies into study, winning scholarships to both Winchester and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he gained a first in history in 1954.

Hodgson’s introduction to the US came in the form of a copy of John Gunther’s classic study Inside USA, a gift from his father on his 14th birthday. He first encountered the real thing in 1955, when, aged 21, he sailed on the Queen Mary to take up a postgraduate scholarship at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. There he worked in the college library, and wrote his MA thesis on the civil war – not the American one of Lincoln but the English one of Cromwell. He also discovered jazz, and the American south, a region for which he developed a special affection.

Back in Britain, he learned his reporting skills on the Times before joining the Observer in 1960, initially to write the paper’s Mammon column. His great opportunity came two years later, when, aged 28, he returned to Washington as the Observer’s correspondent (1962-65), appointed by the editor, David Astor, as one of the gifted young men who would elevate his paper’s foreign coverage. This was a golden time to be a reporter in America and Hodgson loved it.

He covered the push for civil rights in the south, witnessing the tense confrontations as the first black students were escorted into the universities of Mississippi and Alabama, and he was at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington to hear Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech. Events just kept on coming: the Cuban missile crisis, the Kennedy assassination and the complex presidency of Lyndon Johnson, who, even then, Hodgson rated more highly than the liberal commentariat of the day.

Returning to London, he developed his coverage of America as a reporter on the ITV current affairs programme This Week (1965-67) and as editor of the Sunday Times Insight team (1967-71), during which time he co-wrote An American Melodrama (1969) with Bruce Page and Lewis Chester, the story of the 1968 election that brought Richard Nixon to the White House. He anchored LWT’s The London Programme (1976-81), was one of the four founding presenters of Channel 4 News (with Peter Sissons, Trevor McDonald and Sarah Hogg) from 1982 until 1985, and for two years from 1990 was foreign editor of the Independent. He was also a stalwart of Granada’s late-night What the Papers Say.

Friends observed in the younger Hodgson a rumbling tension between his yearning for academic recognition and his enjoyment of the more material pleasures of journalism, a trade that suited his gregarious personality well. He was fortunate in being able to reconcile these conflicting needs as director of the Reuters Foundation (1992-2001), a post that combined mentoring bright young foreign reporters with a fellowship at Green Templeton College, Oxford. The move opened up a world of graduate teaching, both in Britain and the US, which he continued into his 80s.

His Oxford appointment chimed well with the generosity he showed towards aspiring young colleagues. I experienced this personally as we travelled through the American south together in the summer of 1967, researching a television documentary on the civil rights movement. Each day would begin with a reading from the appropriate state guide of the Federal Writers’ Project, an inspiration of FDR’s New Deal, and continue as a free-flowing lecture often late into the evening.

The same spirit inspired his involvement in starting up, with the journalist Ben Bradlee and the literary agent Felicity Bryan, the Laurence Stern fellowship. Since 1980 it has funded a three-month summer programme on the Washington Post for a young British reporter (Guardian beneficiaries of the scheme have included David Leigh, Gary Younge, Audrey Gillan, Jonathan Freedland and Ian Black); after the Covid-19 pandemic it will return as the Stern-Bryan fellowship.

Hodgson’s later books ranged from biographies of the US statesmen Henry Stimson (The Colonel, 1990) and Edward House (Woodrow Wilson’s Right Hand, 2006) to critical studies of the rise of conservatism, including The World Turned Right Side Up (1996) and More Equal Than Others (2004). Always at his best when challenging conventional wisdoms, as in The Myth of American Exceptionalism (2009), he enjoyed particularly showing in A Great and Godly Adventure (2006) that the first Thanksgiving was not celebrated with turkey and cranberry sauce – because there wasn’t any – and that the early American settlers did not see themselves as revolutionaries against the British crown.

Following a serious fall in 2007, he nursed himself back to health by writing a delightful history of the local river near his West Oxfordshire home, Sweet Evenlode (2008). Above all, Hodgson could tell a good story.

In 1958 he married Alice Vidal, and they had two sons, Pierre and Francis. They divorced in 1969, and the following year he married Hilary Lamb, with whom he had two daughters, Jessica and Laura. Hilary died in 2015, and he is survived by his children.

Godfrey Michael Talbot Hodgson, journalist and historian, born 1 February 1934; died 27 January 2021

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion