Abstract

Though the customer journey (CJ) is gaining traction, its limited customer focus overlooks the dynamics characterizing other stakeholders’ (e.g., employees’/suppliers’) journeys, thus calling for an extension to the stakeholder journey (SJ). Addressing this gap, we advance the SJ, which covers any stakeholder’s journey with the firm. We argue that firms’ consideration of the SJ, defined as a stakeholder’s trajectory of role-related touchpoints and activities, enacted through stakeholder engagement, that collectively shape the stakeholder experience with the firm, enhances their stakeholder relationship management and performance outcomes. We also view the SJ in a network of intersecting journeys that are characterized by interdependence theory’s structural tenets of stakeholder control, covariation of interest, mutuality of dependence, information availability, and temporal journey structure, which we view to impact stakeholders’ journey-based engagement and experience, as formalized in a set of Propositions. We conclude with theoretical (e.g., further research) and practical (e.g., SJ design/management) implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last decade, the customer journey (CJ), defined as “the process a customer goes through, across all stages and touchpoints, that makes up the customer experience” (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016, p. 71), has gained prominence among managers and researchers. Though understanding the CJ has long been of interest (e.g., Howard & Sheth, 1969), current developments, including the rise of omni-channel retailing, have revitalized attention to the concept (Shavitt & Barnes, 2020). For example, the Marketing Science Institute’s (2020) Research Priorities state: “A top priority for marketers is to understand and map the CJ” (p. 2), warranting further study in this area.

The literature, to date, boasts important contributions, including the development of CJ conceptualizations (e.g., Novak & Hoffman, 2019), the CJ’s classification into particular (e.g., pre-purchase, purchase, post-purchase) stages (e.g., Van Vaerenbergh et al., 2019), exploration of the CJ’s interface with the customer experience (e.g., Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), and investigation into the effect of specific (e.g., contextual/cultural) contingencies on the CJ (e.g., Vredeveld & Coulter, 2019), among others. However, despite these advances, important gaps remain, as outlined below.

First, owing to its focus on the customer as the central stakeholder, the CJ literature is largely limited to the buyer’s dynamics in his/her journey (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Santana et al., 2020). However, service ecosystems contain not only customers but myriad stakeholders, defined as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of [an] organization’s objectives” (Freeman, 1984, p. 46), including directors, managers, employees, suppliers, owners, strategic partners, collaborators, competitors, policymakers, community organizations, the media, etc. (Hillebrand et al., 2015). These stakeholders are on their own role-related journey, which has, however, received little attention to date. To address this gap in the literature, a broadened, omni-stakeholder perspective of the journey, beyond the CJ alone, is, therefore, needed (Bradley et al., 2021). Correspondingly, we extend the CJ to the stakeholder journey (SJ), defined as “a stakeholder’s trajectory of role-related touchpoints and activities, enacted through stakeholder engagement, that collectively shape the stakeholder experience with the firm.” The SJ comprises—but transcends beyond—the CJ to cover any stakeholder’s role-related journey with the firm (Lievens & Blažević, 2021), thus ushering in a new phase of journey research (Hannay et al., 2020).

By offering the firm an enhanced understanding of its different stakeholders’ needs, goals, activities, and challenges through their respective journeys, firms’ consideration of the SJ (vs. the CJ) allows them to better understand, plan, and orchestrate their stakeholders’ journeys in mutually beneficial ways, in turn improving their stakeholder relationships (Venkatesan et al., 2018). For example, though Tesla’s CJ focus has gained the attention of prospects, expanding its focus to the SJ would allow the company to explicitly recognize its multiple stakeholders’ journey-based dynamics, helping it to more effectively coordinate, leverage, or authorize its relevant SJs and improve stakeholder processes, interactions, and relationships (Kumar & Ramachandran, 2021).

Second and relatedly, the literature has traditionally viewed the CJ in isolation, that is, by considering only the customer through his/her journey (e.g., Tax et al., 2013). While emerging recognition exists of clients journeying together (e.g., on family holidays/in massively multiplayer online games; Hamilton et al., 2021), little is known about different stakeholders’ (vs. merely customers’) intersecting journeys (Ortbal et al., 2016), exposing a second gap in the literature. Addressing this gap, we posit that the SJ traverses or intersects with that of others at relevant touchpoints (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), in turn impacting both these stakeholders’ journeys, positively or negatively. For example, a customer’s purchase based on a supplier’s recommendation transpires at the junction of the customer’s and the supplier’s journeys (vs. in isolation), revealing these journeys’ mutual influence on one another. Specifically, the customer’s (e.g., car) purchase is expected to facilitate his/her (e.g., transportation) goal fulfilment, while also contributing to the supplier’s financial performance (Mish & Scammon, 2010), thus positively impacting both these stakeholders’ journeys. However, a stakeholder’s journey can also hinder or complicate that of another (George & Wakefield, 2018). For example, Apple’s decision to keep its factories open during the pandemic would likely challenge its employees’ journeys. Overall, the firm’s recognition of its different ecosystem-based stakeholders’ journeys, which may intersect with one another, is pivotal, as it permits it to better understand, plan, and manage its activities in line with their respective journeys (Lievens & Blažević, 2021).

To explore these issues, we adopt an interdependence theory perspective, which posits that a stakeholder’s journey is likely to impact and be impacted by that of his/her interaction partner(s) (Kelley & Thibaut, 1959; Scheer et al., 2015). Our analyses rest on interdependence theory’s assumptions that (i) interpersonal interactions are key in fostering stakeholder interdependence, and (ii) stakeholders’ interdependence defines their relational journey (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). We argue that, by fostering more coordinated, improved stakeholder interactions and relationships, a firm’s consideration of its stakeholders’ traversing journeys will not only help it attain superior financial performance (e.g., through revenue/profitability growth), but will also enhance its social- and environmental performance. Here, while a firm’s social performance reflects the results of its “principles of social responsibility, processes of social responsiveness, and policies [and] programs…[that] relate to [its] societal relationships” (Wood, 1991, p. 693), its environmental performance denotes “the results of a [firm’s] management of its environmental aspects” (Trumpp et al., 2015, p. 200). For example, by switching to more affordable, easily disposable lithium iron phosphate batteries (Frith, 2021), Tesla not only facilitates the CJ, but by raising the public perception of its efficiency and environmental responsibility, also aligns its journey with that of stakeholders including employees, managers, lobby groups, the government, and the media, thus supporting its development of value-laden relationships with these stakeholders (Freeman et al., 2010). Consequently, Tesla’s stock price reportedly soared in the days following this announcement (Dir, 2021). Our extension of the CJ to the SJ is, therefore, expected to offer paramount stakeholder relationship management and performance benefits to firms, in turn boosting their triple bottom-line (i.e., financial, social, and environmental) performance (Chabowski et al., 2011). In other words, marketers cannot afford to ignore the SJ.

Addressing these gaps in the literature, this conceptual paper’s objectives are to: (i) advance and explicate the SJ concept, and (ii) explore and map the notion of intersecting SJs using interdependence theory, yielding the following contributions to the marketing-based journey, engagement, and experience literature. First, we move the nascent SJ concept forward based on a thorough review. While pioneering authors have coined the SJ (e.g., Ortbal et al., 2016), a dearth of research has explored the concept in the marketing literature to date (Lievens & Blažević, 2021), warranting the undertaking of this research. Extending the CJ literature, the proposed SJ concept covers any firm stakeholder’s role-related journey with the firm, thus equipping the company with an enhanced understanding of its different stakeholders’ journeys. Relatedly, firm-based recognition of the SJ will allow it to better manage or coordinate its own and its relevant stakeholders’ journeys for mutual benefit, thus yielding improved stakeholder relationship management and performance outcomes (Hannay et al., 2020).

For example, understanding its customers’, suppliers’, and competitors’ journeys helps companies like McDonald’s stay abreast of, influence, and/or suitably orchestrate these journeys in rapidly changing environments (e.g., consumers’ growing demand for healthy food, rising ingredient shortages, and/or rivals’ fast-food innovations), in turn boosting their performance (Tax et al., 2013). Overall, by progressing the SJ’s development, our analyses reveal MacInnis’ (2011, p. 146) integrating purpose of conceptual research, which implies “the creation of a whole [i.e., here, the SJ] from diverse parts” (e.g., the CJ, customer experience, and engagement). Our work also exhibits MacInnis’ (2011) envisioning role of conceptual research, as by generalizing the CJ to the SJ, we cover novel theoretical ground.

Second, we map the SJ in a mosaic of intersecting (e.g., manager/supplier) journeys, thus offering more systemic SJ-based insight (Bradley et al., 2021), as outlined. For example, the SJ captures issues including Starbucks’ and Barnes & Noble’s strategic partnership, which sees these firms’ regularly traversing journeys that are also likely to intersect with those of their respective stakeholders (e.g., customers/employees). That is, by offering enhanced acumen of a stakeholder’s intersecting journey with that of another, our analyses permit the development of novel (e.g., managerial) understanding regarding how to better manage or coordinate relevant SJs, in turn yielding improved firm-based stakeholder relationships and performance. To frame our analyses, we adopt interdependence theory, which posits that stakeholder relationships are defined by interpersonal interdependence or “the degree to which [a stakeholder] relies on an interaction partner, in that his [her] outcomes are influenced by the partner’s actions” (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 355).

As stakeholder interdependence tends to be dynamic (vs. static) through the journey (Kumar et al., 2009), we broaden the SJ beyond the CJ’s typical discrete, single role-related (i.e., purchase) cycle (e.g., Voorhees et al., 2017), to comprise the focal stakeholder’s trans-role cycle relationship with the firm (Novak & Hoffman, 2019). Correspondingly, we view an employee (supplier) journey to cover a worker’s (vendor’s) entire experience with the firm (Parida, 2020), respectively, as discussed further in the section titled Conceptual Development. Specifically, our interdependence theory-informed view maps stakeholders’ structural interdependence in terms of their relevant control, covariation of interest, mutuality of dependence, information availability, and temporal journey structure in their journey with the firm (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003), thus overlaying the CJ’s traditional discrete view with a more relational SJ perspective (Hamilton & Price, 2019). We summarize our findings in a set of interdependence theory-informed Propositions of the SJ that offer novel insight and serve as a springboard for further research.

The paper is organized as follows. Next, we review key literature addressing the CJ and stakeholder engagement, the latter of which emerges as a vital SJ-shaping catalyst. We, then, propose our SJ conceptualization and set forth an interdependence theory-informed SJ map that depicts several stakeholders’ transpiring and at times, intersecting, journeys. We proceed by analyzing stakeholders’ interdependence theory-informed structural interdependence tenets through the SJ, as formalized in a set of Propositions. We conclude by discussing key implications that arise from our analyses.

Literature review

Below, we review pertinent CJ and stakeholder engagement literature, on which we draw to inform our SJ-based theorizing in the next section.

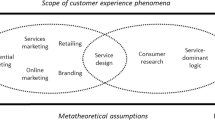

Customer journey research

Though the CJ has received extensive attention (e.g., Kuehnl et al., 2019), the SJ, which covers any stakeholder’s (e.g., employee’s, customer’s, manager’s, competitor’s, etc.) journey with the firm (Lievens & Blažević, 2021), remains under-explored in the marketing literature to date, despite its importance for understanding marketing- or service ecosystems (Varnali, 2019). We, therefore, review the CJ literature below, which offers an important foundation for our SJ-based analyses.

To understand the CJ, we first review existing CJ conceptualizations (see Table 1), from which we derive the following observations. First, the CJ describes the customer’s progression through a traditionally sequential trajectory of steps in completing his/her goal of making a purchase (Siebert et al., 2020), which collectively capture the customer experience. The CJ, thus, covers a customer’s entire experience in making a purchase from the firm, from start to finish (e.g., ranging from the individual’s initial product information search to his/her post-purchase evaluation; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). The CJ, therefore, offers a process-based view of a customer’s purchase cycle (Edelman & Singer, 2015), rendering time an important factor in the CJ. For example, different journeys will tend to vary in length, and different time intervals may exist in between purchase cycles. Here, a customer’s repurchase of an item is typically modeled as a separate journey (Siebert et al., 2020; Voorhees et al., 2017), revealing the CJ’s iterative nature. However, we assert that the SJ—and thus, its constituent sub-concept of the CJ—should extend beyond a single role cycle, as outlined. Specifically, we advocate a more relational, trans-role cycle view that maps customers’ evolving interdependence through their journey with the firm (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), as generalized to the SJ in the section titled The Stakeholder Journey: An Interdependence Theory Perspective.

Though the CJ is traditionally viewed to comprise a predetermined sequence of typically company-designed steps (Santana et al., 2020), scholars are increasingly recognizing the need for a more fluid view that accommodates different potential sequences of CJ steps. For example, clients may co-design their own journey (vs. following a company-orchestrated CJ), offering them greater control over their journey and shifting the company’s role from journey director to -facilitator. Here, customers may decide to skip, skim, alter, or repeat specific journey stages (Hamilton et al., 2021), illustrating the CJ’s potential fluidity. For example, a prospect’s reading of product reviews may alter the course of his/her planned journey if (s)he decides against purchasing the item (Halvorsrud & Kvale, 2017).

Second, the journey comprises multiple touchpoints, defined as “points of human, … communication, spatial, and electronic interaction collectively constituting the interface between an enterprise and its customers” (Dhebar, 2013, p. 200), revealing the CJ’s multi- or omni-channel nature (Herhausen et al., 2019). Touchpoints may also allow customers to interact with other firm stakeholders (e.g., fellow customers), exposing potential touchpoint-based stakeholder heterogeneity (Baxendale et al., 2015). Relatedly, touchpoints can be brand-, brand partner-, customer-, or externally-owned (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). For example, a firm’s (i.e., brand-owned) interfaces include its physical retail stores and its digital touchpoints (e.g., website, social media pages), yielding a potentially hybrid phygital (i.e., physical/digital) CJ (Mele & Russo-Spena, 2021). Through the CJ, customers may primarily interact with the firm via a single touchpoint (e.g., its call center), or use multiple touchpoints (Richardson, 2010).

Third, as noted, the CJ is inextricably linked to the customer experience (CX), defined as “a multidimensional construct focusing on a customer’s cognitive, emotional, behavioral, sensorial, and social responses to a firm’s offerings during the customer’s entire purchase journey” (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016, p. 71). Jaakkola and Alexander (2018) suggest that the customer’s journey-based experience is driven by customer engagement, defined as “a customer’s …volitional investment of operant [e.g., cognitive/emotional] and operand [e.g., equipment-based] resources in [his/her] brand interactions” (Kumar et al., 2019, p. 141). Therefore, while the customer experience depicts a customer’s role-related responses (i.e., role outputs; Brakus et al., 2009), it is also important to understand how the individual’s role investments or inputs (i.e., engagement) drive these responses, which, however, remains nebulous to date (e.g., Vredeveld & Coulter, 2019). Correspondingly, we next explore stakeholder engagement’s role in shaping stakeholders’ journey-based experience.

Stakeholder engagement research

As noted, authors including Venkatesan et al. (2018), Jaakkola and Alexander (2018), Demmers et al. (2020), and Mele and Russo-Spena (2021) identify customer engagement as a vital CJ-shaping conduit. Analogously, we infer stakeholder engagement’s fundamental role in the transpiring SJ (Lievens & Blažević, 2021). In what follows, we, therefore, review the stakeholder engagement literature, as applied to the SJ.

Key stakeholder engagement conceptualizations are listed in Table 2, which reveal the following observations. First, the concept’s definition and indeed, its ideology, are debated (e.g., Harmeling et al., 2017). In its home turf, the strategic management and business ethics literature, authors typically address stakeholder engagement from a company perspective (see Table 2: e.g., Greenwood, 2007), as also adopted in this article. Correspondingly, our analyses offer particular value to firms wishing to understand, plan, manage, or coordinate their different stakeholders’ journeys, which primarily transpire through the focal stakeholder’s and his/her interaction partner’s role-related engagement (e.g., Venkatesan et al., 2018).

Second, despite its definitional dissent, broad consensus exists regarding stakeholder engagement’s interactive nature (Viglia et al., 2018), in line with customer engagement research (e.g., Meire et al., 2019). Citing Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, interaction has been defined as “mutual or reciprocal action or influence” (Vargo & Lusch, 2016, p. 9). Interactive stakeholder engagement can be mutually beneficial for the involved stakeholders (e.g., customers helping each other; Fassin, 2012). However, if stakeholder interests diverge, we expect stakeholder engagement to either be far less reciprocal (e.g., competing firms each optimizing their own goal pursuit) or to display a level of calculated (vs. true) reciprocity (Amici et al., 2014). For example, a co-worker may only do another a favor with the expectancy of it being reciprocated in the future.

Stakeholder engagement is pertinent in the SJ, which sees stakeholder-to-stakeholder interactivity at its relevant touchpoints (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Venkatesan et al., 2018). We, however, argue that stakeholder engagement’s interactivity not only transpires in stakeholders’ touchpoint-based interactions, but also, outside their role-related touchpoints (Storbacka, 2019). For example, amidst their work meetings, employees will privately work on their assigned tasks, revealing their continued (e.g., cognitive) engagement beyond their role touchpoints alone (Schaufeli et al., 2006).

Third, in marketing, stakeholder engagement is commonly viewed as a stakeholder’s resource investment in, or contribution to, his/her role-related interactions (Hollebeek et al., 2019; Kumar & Pansari, 2016). This view posits that the more of their resources stakeholders invest in an interaction, the higher their engagement, leading us to equate the notions of engagement-based resource investments (Brodie et al., 2016) and engagement-based contributions (Pansari & Kumar, 2017). Stakeholder engagement, thus, reflects those tangible (e.g., equipment-based) and intangible (e.g., cognitive) resources that stakeholders endow in their role interactions (Kumar et al., 2019). For example, though managers may invest their cognitive/behavioral resources in performing their jobs (Schaufeli et al., 2006), suppliers contribute financial resources to their role interactions (e.g., by purchasing stock). Moreover, though these contributions can be voluntary (e.g., an employee choosing to do a good job at work), they may also transpire less volitionally through the journey (e.g., employees executing undesired tasks; Hollebeek et al., 2022a).

Fourth, our review reveals stakeholder engagement’s multidimensionality. Extending the customer engagement literature, most authors view stakeholder engagement to comprise cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and/or social facets (Brodie et al., 2019). For example, Viglia et al., (2018, p. 405) note that stakeholder engagement reflects a stakeholder’s “emotional and cognitive … engagement [to] trigger… behavioral activation” through his/her journey. Based on our review, we adopt Hollebeek et al.’s (2022a) recent conceptualization that acknowledges the outlined stakeholder engagement tenets (see Table 2), as applied to the SJ below.

Conceptual development

Extending the customer to the stakeholder journey

Our review highlighted three core CJ tenets that we generalize to the SJ below. First, the SJ portrays a focal stakeholder’s progression through a trajectory of fixed or more fluid role-related steps (Hamilton et al., 2021; Ortbal et al., 2016), starting with the individual’s initial firm-related information search (Santana et al., 2020). For example, while the employee journey commences with a prospective worker vetting the firm as a potential new workplace, a policymaker’s journey begins with a public servant’s inception of new firm-impacting regulation. The SJ proceeds to cover all the focal stakeholder’s interactions, and relationship, with the firm, and concludes upon his/her final experience with the firm (e.g., owners selling their stake in the company or customers’ post-purchase evaluation of the firm’s offerings; Novak & Hoffman, 2019). Further, the SJ will often run a more adaptable (vs. fixed) course (e.g., as stakeholder sentiment/needs or external factors change; Vakulenko et al., 2019), as outlined. For example, a competitor’s journey may be altered by COVID-19.

Second, the SJ features multiple touchpoints, which we define as the (e.g., physical/digital) stakeholder-connecting (e.g., meeting-, email-, or phone-based) interfaces, which, as noted, can be brand, brand partner, customer, or externally-owned (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). These touchpoints bear particular relevance to our analysis, as they permit the intersecting of a stakeholder’s journey with that of another (Jaakkola & Alexander, 2018; Ortbal et al., 2016). For example, an employee’s and a manager’s journey coincide during a meeting at the office, or a customer’s and a firm’s journey coalesce through the client’s order. However, we argue that stakeholders’ engagement extends beyond these journey-based touchpoints alone, as outlined. In other words, outside their role-related touchpoints, stakeholders may still engage, but here, they do so privately with their role and its requirements, responsibilities, and activities (vs. via touchpoint-based interactions with others; Venkatesan et al., 2018).

Third, in line with the CJ literature, we view the SJ to holistically depict the focal stakeholder’s role experience (e.g., Siebert et al., 2020) or his/her cognitive, emotional, behavioral, sensorial, and social role-related responses (Brakus et al., 2009; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Based on our assertion that stakeholder engagement transpires both at and outside of stakeholders’ journey-based touchpoints, we posit that stakeholder engagement, like the stakeholder experience, pervades the entire SJ. However, the two differ as follows: While stakeholder engagement denotes the focal stakeholder’s role-related resource investment or contribution (i.e., role inputs) through his/her journey, the stakeholder experience represents the individual’s journey-based (e.g., cognitive) responses (i.e., role outputs), as outlined. That is, by virtue of its role investments, stakeholder engagement is instrumental in shaping or enacting the SJ, in turn affecting the stakeholder experience (Lievens & Blažević, 2021). Drawing on these tenets and in line with our first contribution, we define the SJ as:

“A stakeholder’s trajectory of role-related touchpoints and activities, enacted through stakeholder engagement, that collectively shape the stakeholder experience with the firm.”

An overview of the CJ and the SJ, including their respective definitions, hallmarks, and theoretical associations (e.g., with customer/stakeholder engagement and experience), is provided in Table 3.

The stakeholder journey: An interdependence theory perspective

In line with our second contribution, we observe that the SJ does not occur in isolation, but transpires in a network of intersecting journeys, necessitating a more systemic view (Bradley et al., 2021). That is, though prior research suggests that interacting stakeholders (partners) exhibit some level of interdependence (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Scheer et al., 2015), the CJ literature, to date, largely overlooks customers’ potential symbiotic role-related interactions through their journey with the firm (Edelman & Singer, 2015). Extending this observation to the SJ, we adopt an interdependence theory perspective to glean further insight.

Interdependence theory posits that interpersonal interactions are a function of interacting partners’ engagement, characteristics, and context (Kelley & Thibaut, 1959; Kelley et al., 2003), which forge a level of stakeholder interdependence, defined as “the process by which interacting [stakeholders] influence one another’s experiences” (Van Lange & Balliet, 2014, p. 65). Interdependence, thus, implies that “every move of one [stakeholder] will …affect the other[s]” in their respective journeys (Lewin, 1948, pp. 84, 88), in turn continually shaping stakeholders’ interdependence with one another.

In other words, rather than each running their own individual course, different stakeholders’ journeys affect and are affected by one another (Thomas et al., 2020), exposing SJ-based interdependence (Hamilton et al., 2021). Consequently, not only the focal stakeholder’s engagement, but also, that of his/her interaction partner(s), will mutually shape one another’s journeys, both at and outside of their role-related touchpoints. For example, in addition to a manager’s touchpoint (e.g., store)-based interactions with his/her customers, the former’s engagement in adjusting product specs (i.e., outside their touchpoint-based interactions) is also likely to impact both their journeys (e.g., by altering the client’s purchase behavior). Therefore, the term “stakeholder engagement” in our SJ conceptualization refers not only to the focal stakeholder’s engagement, but also, to that of his/her interaction partner(s) (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), revealing their interdependence.

Figure 1 depicts a stakeholder journey map (Lievens & Blažević, 2021), as informed by interdependence theory. Extending the notion of a CJ map, which depicts a customer’s interactions with a firm (Rosenbaum et al., 2017), SJ maps are “a visualization tool used to gain insight about [stakeholder interactions]” through their journey with the firm (Ortbal et al., 2016, p. 250). In Fig. 1, we depict a focal stakeholder’s engagement (i.e., role input-based resource contributions; Pansari & Kumar, 2017) on the x-axis, and stakeholder experience, viewed as the stakeholder’s role output-based (e.g., cognitive/sensorial) responses (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), on the y-axis. Our illustrative mapping portrays three SJs, including a manager’s journey (black), an employee’s journey (blue), and a customer’s journey (red), respectively. Additional (e.g., supplier) journeys can also be added as required (Ortbal et al., 2016). As shown, the SJ sees a fluctuating stakeholder experience over time (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016).

The depicted SJs also intersect at relevant touchpoints, defined as stakeholder-connecting (e.g., meeting-, email-, or phone-based) interfaces (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020). Though theoretically, the minimum number of intersecting SJs is two, the yellow (vs. white) touchpoints in Fig. 1 illustrate the intersecting of the three depicted SJs (i.e., manager-, employee-, and customer journeys). For example, a manager, employee, and customer may collaborate to resolve the client’s complaint. Overall, dyadic (triadic) interactions feature two (three) intersecting SJs, respectively, etc. In general, the greater the number of intersecting SJs, the higher the inherent complexity in meeting each of the involved stakeholders’ needs, goals, and wants, particularly under clashing stakeholder interests (Freeman et al., 2010).

The SJs shown also contain multiple of each stakeholder’s role cycles, thus extending beyond the CJ’s typical single-purchase cycle view to reflect the SJ’s more relational fabric (Hamilton et al., 2021), as outlined. For example, for the CJ, three purchase cycles are shown in Fig. 1, which would traditionally be viewed as three distinct CJs. However, our more relational, trans-role cycle view of the SJ (and thus, the CJ) permits assessments of the focal stakeholder’s cross-role cycle (e.g., interactional) dynamics. In other words, we argue that the SJ is best viewed as the totality of a stakeholder’s role cycles (vs. a single cycle), thus offering insight into his/her cumulative experience with the firm. Correspondingly, Fig. 1 shows multiple role cycles for the three depicted stakeholders’ journeys (e.g., for the CJ, three purchase cycles are shown that are separated by short, vertical black lines). For the manager and employee journeys, three and two role cycles are shown, respectively, with the aggregate of their particular role cycles reflecting their respective journey with the firm. The SJ may, in turn, contain different phases (e.g., relationship initiation, development, maturity, or decline; Siebert et al., 2020).

To fuel the SJ’s unfolding, the focal stakeholder’s engagement, or his/her (e.g., cognitive/emotional) resource investment in his/her role-related interactions (Hollebeek et al., 2022a), is pivotal, as discussed. That is, stakeholder engagement incites or maintains the SJ (Demmers et al., 2020; Venkatesan et al., 2018). Take the employee (or customer) journey, which covers a worker’s (buyer’s) engagement throughout his/her entire journey with the firm, ranging from the individual’s initial job (product)-related information search to his/her post-employment (post-purchase) evaluation of the firm, respectively (e.g., Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Novak & Hoffman, 2019). We next explore stakeholders’ structural interdependence in their intersecting journeys (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978).

Stakeholders’ structural interdependence through the SJ

Below, we outline the role of interdependence theory’s structural interdependence tenets of stakeholders’ control, covariation of interest, mutuality of dependence, information availability, and temporal journey structure (see Table 4) on the SJ’s unfolding (Kelley et al., 2003). We focus on stakeholders’ structural (vs. more transient) interdependence facets, given their relative stability across interactions and situations (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), thus offering more generalizable insight. For example, illustrating stakeholder control, a fiduciary lawyer-client relationship contains an inherent control imbalance, given the former’s specialist knowledge that the latter requires (but lacks), thus systematically impacting both these stakeholders’ journeys. From our analyses, we develop a set of interdependence theory-informed Propositions that outline the effect of stakeholders’ control, covariation of interest, mutuality of dependence, information availability, and temporal journey structure on their overall engagement and experience, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In the figure, we include stakeholder engagement on the x-axis, and stakeholder experience on the y-axis, as outlined, which are viewed to exhibit differing degrees of valence-based positivity through the SJ (Bowden et al., 2017), depending on the particular structural interdependence tenet observed (e.g., stakeholder control). Thus, while Fig. 1 presents the big picture of stakeholders’ potentially intersecting journeys, Fig. 2 illustrates the effect of specific structural interdependence tenets on stakeholder engagement and experience through the SJ.

Control

Control, which reflects the balance of power among stakeholders (Grimes, 1978; see Table 4), is an important factor in stakeholders’ journey-based interdependence (Varnali, 2019). For example, if a business partner can unilaterally cause a firm pleasure (vs. pain) or govern its choices, the former is said to have high control over the latter. Interdependence theory distinguishes three types of control, including stakeholder, partner, and joint control (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), as discussed further and applied to the SJ below, in line with Hamilton et al. and’s (2021, p. 75) suggestion to explore the “dynamics and relative power structures” characterizing interdependent journeys.

Stakeholder control

Extending Lemon and Verhoef’s (2016) notion of customers’ journey-based control, we explore the role of interdependence theory-informed stakeholder control, defined as “the impact …of [a stakeholder’s] actions… on [his/her] own [journey-based] outcomes” (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 354). High stakeholder control implies a stakeholder’s ability to choose his/her own engagement relatively independently from that of a focal other through his/her journey, exposing his/her comparatively low reliance on the other (Kelley et al., 2003; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2008).

For example, leading companies like Apple tend to possess high stakeholder control (vs. their competitors), allowing them to remain relatively unaffected by their rivals’ (e.g., promotional/product launch) activity, both at and outside of their respective journeys’ touchpoints (Shavitt & Barnes, 2020). Apple is, therefore, able to choose its own course largely irrespective of Samsung’s actions, revealing its relatively autonomous engagement (Hollebeek et al., 2021). In other words, high stakeholder control enables Apple to determine or adjust its journey’s course comparatively independently from that of Samsung (e.g., by adopting a highly inimitable/legally protected R&D strategy), allowing its SJ to proceed in an array of desired directions, as shown in the sample scenario depicted in Fig. 2: P1a. Here, we portray Apple’s random base journey, shown by a solid black line. The dashed lines reflect the company’s ability to deviate off its base course, which Apple, given its high stakeholder control, has the power to command, determine, or implement, revealing its relatively autonomous or sovereign (i.e., positive) engagement and illustrating Halvorsrud et al.’s (2016) notion of journey-based deviation.

Consequently, high stakeholder control is expected to spawn a range of potential SJ paths, as selected or driven by Apple. Though the SJ’s alternate (dashed) paths can yield a diminished stakeholder experience, theoretically (as shown by the downward sloping path in Fig. 2: P1a; Bradley et al., 2021), an enhanced, upward sloping experience is more likely to transpire under high stakeholder control, given its inherently elevated stakeholder power and influence (Kelley et al., 2003). Therefore, individuals’ increasingly autonomous engagement, as afforded by high stakeholder control (Benford et al., 2021), progressively liberates or frees their role experience, as illustrated by the two upward sloping alternate journey paths in Fig. 2: P1a. Formally,

- P1a

A stakeholder’s rising stakeholder control will see his/her more autonomous engagement in the SJ, increasingly liberating the stakeholder experience.

Partner control

Partner control refers to the degree to which a stakeholder’s interactional “outcomes [are] controlled by [his/her partner’s] unilateral actions” (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 355) at or outside their journey-based touchpoints (e.g., Kranzbühler et al., 2019). For example, if a manager (or small firm) is dependent on a director’s (or competitor’s) processes, actions, or decisions for a positive result, the latter is high in partner control. At a journey touchpoint (e.g., a meeting), a stakeholder (e.g., a manager) may steer another’s (e.g., an employee’s) role-related journey (e.g., by instructing him/her to work on specific tasks; Parida, 2020), revealing the former’s elevated partner control. Moreover, outside the journey’s touchpoints, the manager can also influence the employee’s journey (e.g., through decision-making behind closed doors; Hollebeek et al., 2022a). High partner control, thus, implies the less powerful stakeholder’s journey-based engagement and experience resting, to a significant degree, in the hands of his/her more powerful partner.

As high partner control exposes a stakeholder’s power over another, it will tend to direct or prescribe the other’s journey, thus typically disempowering his/her role engagement (Li & Feng, 2021). For example, under high partner control, stakeholders (e.g., employees) can be ordered to perform undesired tasks, which they—given their comparatively low power—are typically required to execute (e.g., to minimize their partner’s implementation of sanctions; Dawkins, 2014).

The sample high partner control scenario in Fig. 2: P1b depicts the less powerful stakeholder’s (e.g., small firm’s) base journey by a solid line. As its engagement is disempowered (i.e., negatively affected) by its more powerful partner (e.g., leading firm; Li & Feng, 2021), the dashed lines in the figure reveal the small firm’s limited ability to pursue alternate courses in its journey, as directed by the leading firm (e.g., by setting industry price levels). In turn, the small firm’s disempowered engagement curbs or curtails its role experience (i.e., rendering it less positive), as its partner has the power to determine its SJ’s course to a significant extent (Halvorsrud & Kvale, 2017). For example, by offering low prices based on economies of scale, leading online retailers (e.g., Alibaba) have a level of control over locally owned stores by pushing them to also reduce their prices to stay in business, though these retailers typically lack the resources to do so long-term. As shown in Fig. 2: P1b, we postulate:

- P1b

A stakeholder’s rising partner control will see his/her more disempowered engagement in the SJ, increasingly curtailing the stakeholder experience.

Joint control

Joint control implies that a stakeholder’s role experience is “controlled by the partners’ joint” engagement (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 355), revealing interacting stakeholders’ interdependence in achieving an auspicious outcome through their journey (Hamilton et al., 2021; Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). For example, high joint control exists when a manufacturer’s (e.g., Huawei’s) outcomes depend on the interplay of its engagement with that of its retailers, including Target or Amazon (Kelley et al., 2003; Lievens & Blažević, 2021).

Under high joint control, the involved stakeholders’ goals may exhibit differing degrees of alignment, in turn affecting the unfolding of their respective journeys, both at and outside of their touchpoints (Richardson, 2010). For example, while joint CJs (e.g., family holidays) may see clients’ high journey-based goal alignment (Thomas et al., 2020), an employee’s journey-related (e.g., pay rise) goal may not fully align with that of his/her manager. Therefore, the more stakeholders’ goals differ, the greater the need for joint control-based bargaining and negotiation to streamline their respective journey-based engagement (Wilson & Putnam, 1990), in turn impacting the stakeholder experience.

For example, joint venture partners’ differing objectives raise a need for the parties to agree on the appropriate course of action. This negotiation process is likely to see a level of stakeholder compromise, rendering stakeholders’ engagement more concessional and thus, less positive, under rising levels of compromise in their journey (Hamilton et al., 2021; Schwartz et al., 2002). For example, to ensure its shelves remain well stocked, Walmart engages with its suppliers to reach a suitable compromise (e.g., by agreeing on product quality/pricing), as shown in the sample high joint control scenario in Fig. 2: P1c. Given high joint control, these stakeholders may decide to meet in the middle by negotiating a satisfactory but suboptimal solution, thus foregoing each party’s preferred strategy (e.g., for Walmart, high product quality at a low price) in favor of a mutually agreed one (e.g., standard quality at an average price; Hamilton et al., 2021).

While the left side of Fig. 2: P1c depicts Walmart’s less concessional (i.e., more positive) engagement to reach a compromise with its supplier, rightward movement along the x-axis reveals its progressively more concessional (i.e., less positive) engagement to realize a mutually acceptable compromise in its journey (Hollebeek et al., 2022a; Shavitt & Barnes, 2020). The company’s less concessional engagement, in turn, yields its relatively positive, less satisficed (i.e., superior) experience that contains a higher satisfy (vs. sacrifice) component (Winter, 2000), as depicted by the elevated y-values on the figure’s left side. Thus, if Walmart gets its way in its supplier negotiations, its engagement should be less concessional, generating an exalted experience, as shown (left of Figure P1c). Conversely, if Walmart gives (vs. takes) more in the bargaining process, its more concessional engagement triggers a less positive, more satisficed experience that features a higher sacrifice (vs. satisfy) aspect (Schwartz et al., 2002), as shown on the right side of Fig. 2: P1c. That is, the higher stakeholders’ joint control, the greater their typical need to negotiate to move forward, yielding their more concessional engagement and satisficing the stakeholder experience. Formally,

- P1c

A stakeholder’s rising joint control with another will see his/her more concessional engagement in the SJ, increasingly satisficing the stakeholder experience.

Covariation of interest

Next, we address the effect of stakeholders’ covariation of interest through their journey, which denotes “whether the course of action that benefits [stakeholder A also] benefits [stakeholder B]” (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 356; see Table 4). For example, manufacturers (e.g., Bosch) may prioritize their distributors’ (vs. retailers’) interest by offering the former price discounts or by over-supplying product, even though their retailers lack shelf space, revealing these stakeholders’ (partially) diverging journey-based interests. Theoretically, covariation of interest ranges from stakeholders’ perfectly corresponding interests (known as coordination) to completely conflicting interests (i.e., competition; Deutsch, 1949), as explained further and applied to the SJ below.

Coordination

Coordination occurs when stakeholders seeking to achieve outcomes in their own best interest simultaneously advance outcomes in the best interest of their partner (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 356), implying the existence of stakeholders’ compatible journey-based goals (Van Lange & Balliet, 2014). For example, career-minded graduates will typically work hard, both at and beyond their touchpoint-based interactions (Rosenbaum et al., 2017), to enhance their career prospects, thereby also benefiting their employer. In coordination, one’s partner’s own goal pursuit, therefore, also benefits the focal stakeholder, given stakeholders’ aligned journey-based goals (Deutsch, 1949), akin to Thomas et al.’s (2020, p. 9) CJ-based “fields of alignment.” For example, the above employer’s training program that is designed to advance the organization will also benefit the hired graduates (e.g., by gaining valuable skills/experience).

As full coordination (i.e., stakeholders’ completely corresponding journey-based goals) remains relatively rare in practice, intersecting SJs tend to be characterized by partial coordination, revealing individuals’ partly converging interests with those of their partner (Hillebrand et al., 2015). Correspondingly, we expect the partial coordination of a stakeholder’s journey-based interests with that of another to boost his/her positive engagement to the extent that it fulfils his/her interests (Thomas et al., 2020; Wolf et al., 2021). For example, Ph.D. students’ joint publications with their adviser tend to advance both these stakeholders’ careers, exposing the apparent coordination of their respective journeys. However, while the adviser may agree to referee in the student’s job applications (i.e., revealing his/her positive engagement; Hollebeek et al., 2022a), (s)he may also feel threatened by the student’s achievements (e.g., concerns of the latter overtaking him/her on the career ladder), which can render his/her engagement more negative (e.g., by understating the candidate’s abilities to prospective employers), illustrating these stakeholders’ partial (vs. full) coordination through their respective journeys (Gnyawali & Charleton, 2018; Tax et al., 2013).

Extending this rationale, we posit that stakeholders’ coordination-incited positive engagement allies or brings together their respective journeys (Lievens & Blažević, 2021; Thomas et al., 2020). For example, researchers in related topic areas may decide to join forces, thus aligning their respective engagement, as shown in the sample scenario in Fig. 2: P2a. In turn, these stakeholders’ allied SJ-based engagement is expected to harmonize or unify their respective role experience (Hänninen et al., 2019), as depicted by both stakeholders’ upward sloping journeys in Fig. 2: P2a. We propose:

- P2a

A stakeholder’s rising coordination with another will see their more aligned engagement in the SJ, increasingly harmonizing their respective stakeholder experience.

Competition

Competition transpires when the interactional outcomes that are positive to one stakeholder are negative to his/her partner (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Given its inherently diverging stakeholder interests, competition may see a festering level of stakeholder antipathy or enmity toward one another (Freeman et al., 2010; Gnyawali & Charleton, 2018), rendering the involved stakeholders’ engagement more negative. For example, employees competing for a promotion, or petrol companies (e.g., Chevron) contesting the same set of scarce (oil) resources as their competitors display clashing interests, which can raise their oppositional engagement through their journey (Parmar et al., 2010). While this negative engagement can manifest at stakeholders’ journey-based touchpoints (e.g., through bullying/extortion), it can also transpire outside these (e.g., a stakeholder defaming another behind his/her back; Hollebeek et al., 2022a).

In other words, as competition features the focal stakeholder’s (e.g., Chevron’s) clashing interest with that of others (e.g., its competitors; Wolf et al., 2021), it can arouse one partner’s or both partners’ antagonistic journey-based engagement toward the other (i.e., by instigating a price war to drive the competition out of business). In turn, this rivalrous, adversarial engagement will tend to separate these stakeholders’ journeys (e.g., by reducing/removing their journey-based touchpoints), as shown in the sample scenario in Fig. 2: P2b. For example, faced with a Chevron-instigated petrol price war, B.P. may decide to diversify its business (e.g., by shifting to supplying electricity for hybrid/electric vehicles), thus divorcing their SJs and individuating their respective stakeholder experience (Klein et al., 2020). Even if stakeholders (e.g., those high in stakeholder control) choose to confront their partner regarding their opposing interests (e.g., through litigation), post-this intervention they are expected to each go their own separate ways, thus isolating or individuating their role experience from one another. We postulate:

- P2b

A stakeholder’s rising competition with another will see his/her more antagonistic engagement toward the other in the SJ, increasingly individuating the stakeholder experience.

Mutuality of dependence

Mutuality of dependence describes “the degree to which two people are equally dependent on one another” (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003, p. 355; see Table 4), akin to the notions of relative dependence or dependence (a)symmetry (e.g., Kumar et al., 1995). High (low) mutuality of dependence reveals stakeholders’ relatively equal (unequal) dependence on each other, respectively. Under low mutuality of dependence, the less dependent partner (e.g., a director) is likely to exercise greater (e.g., decisional) power at or outside his/her journey-based touchpoints with the more dependent partner (e.g., an employee; Vakulenko et al., 2019). The latter, by contrast, typically carries the greater burden of interaction costs (e.g., by making sacrifices) and is more vulnerable to possible journey-based oppression, abandonment, exploitation, threats, or coercion (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2008). Under low mutuality of dependence, the more dependent partner’s journey-based engagement is, thus, likely to be more negatively valenced (Hollebeek et al., 2022b).

Interactions characterized by high mutuality of dependence tend to feel safer (Kelley et al., 2003), as both partners rely on each other to a comparatively equal degree, rendering stakeholders more likely to display (relatively) positive, benevolent engagement toward one another through their respective journeys (Bowden et al., 2017). For example, though IKEA’s weekly sales will, to some degree, be impacted by its competitor’s (e.g., sales) promotion offered in this period, the latter’s sales are equally likely to suffer from IKEA’s (e.g., future) promotion, leading the competitor to behave in a more supportive (vs. opportunistic) manner toward IKEA (e.g., by limiting its discount period/amount). Through these relatively sympathetic actions, the discounting firm exhibits positive, benevolent engagement toward IKEA, which may, however, be primarily driven by its desire to minimize IKEA’s future retaliation, rather than genuine concern for it per se (Amici et al., 2014; Voorhees et al., 2017). Correspondingly, the sample scenario in Fig. 2: P3 depicts two mutually dependent SJs featuring relatively benevolent stakeholder engagement (Hamilton et al., 2021), in turn triggering the depicted stakeholders’ comparatively agreeable, pleasant journey-based experience (Rather et al., 2021). We posit:

- P3

A stakeholder’s rising mutuality of dependence with another will see his/her more benevolent engagement toward the other in the SJ, rendering the stakeholder experience increasingly agreeable.

Information availability

Information availability refers to a stakeholder’s level of access to interaction-related information (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003; see Table 4), including objective (e.g., factual) and subjective (e.g., hearsay-based) information, through his/her role journey (Hollebeek et al., 2019). Information availability is an important structural interdependence tenet, as stakeholders typically value being informed about such issues as their partner’s interactional motives, goals, agenda, circumstances, etc., both at and outside of their journey-based touchpoints (Rosenbaum et al., 2017; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003).

Interdependence theory posits that while low information availability is typically plagued by interactional issues including ambiguity, misunderstandings, or fallouts (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2008), high information availability tends to enhance interactional transparency and effectiveness through the SJ. For example, if a retailer (e.g., Costco) holds salient information about its distributor’s self-interested goals (e.g., by limiting its supply to Costco to non-leading/B-brands, while supplying leading brands to other retailers), Costco’s actions are likely to differ (vs. in the absence of this information; Kelley et al., 2003). That is, the availability of this information will tend to affect Costco’s engagement with its merchant (e.g., by negotiating better terms/switching distributors). Information availability can also differ across stakeholders, which is known as information asymmetry (Bergh et al., 2019). For example, managers are likely to have access to more information about their employees than vice versa.

We argue that greater information availability will typically see partners feel more confident to invest (i.e., engage) in their journey-based interactions, owing to elevated interactional clarity and certainty. That is, the rising availability of high-quality information progressively informs stakeholders’ journey-based engagement, as it enables partners to assess the situation and plan their desired course of action (Kuehnl et al., 2019). In turn, a more placid, less volatile stakeholder experience is anticipated to result, as shown in Fig. 2: P4. Here, Costco’s base course is again represented by a solid line, with the dashed line exposing high information availability’s volatility-reducing effect on the SJ. As another example, long-term employees or relationship marketing implementing firms are likely to hold extensive information about their partner (i.e., employer/customers, respectively), fostering their understanding of, and trust in, their partner’s needs, motives, and preferences (Palmatier et al., 2006), in turn stabilizing their journey-based experience (Kim et al., 2018). We postulate:

- P4

A stakeholder’s rising information availability will see his/her more informed engagement in the SJ, increasingly stabilizing the stakeholder experience.

Temporal journey structure

Interdependence theory’s final structural interdependence tenet of temporal journey structure rests on the notion that interactions and relationships are evolving, dynamic (vs. static) phenomena, requiring an understanding of stakeholder interdependence in terms of its timing and process through the SJ (Kelley, 1984; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2008; see Table 4). In this vein, we highlight the importance of SJ duration (De Pourcq et al., 2016): The longer an SJ, the more role cycles and/or touchpoints it will typically contain (Shavitt & Barnes, 2020), affording the focal stakeholder an enhanced opportunity for role-related learning (e.g., by repeating, revisiting, or modifying specific role tasks/steps; Mena and Chabowski, 2015). For example, since its inception in 1892, Coca-Cola’s journey contains millions, if not billions, of role cycles and touchpoints, thus progressively training its (e.g., managers’/employees’) journey-based engagement, including by teaching them regarding the optimal resource type(s) and quantity to invest in specific role-related interactions (e.g., manufacturing/hiring activity).

Stakeholders’ progressively trained engagement, therefore, exposes their rising role proficiency, including through a growing capacity to leverage their journey-based resource investments (Hollebeek et al., 2019), as shown in the sample scenario in Fig. 2: P5. For example, more (vs. less) skilled Coca-Cola stakeholders’ (e.g., employees’ or contractors’) engagement can see a constrained set of resources go further, thus enhancing firm relationships and/or performance. In turn, this progressively trained engagement is expected to yield a more efficient, streamlined (i.e., more positive) stakeholder experience, as shown by the upward-sloping curve in Fig. 2: P5. We theorize:

- P5

Longer journeys will see more trained stakeholder engagement in the SJ, yielding an increasingly efficient stakeholder experience.

In sum, this section explored the effect of interdependence theory’s structural interdependence tenets of stakeholders’ control, covariation of interest, mutuality of dependence, information availability, and temporal journey structure on SJ-based stakeholder engagement and experience, as summarized in the Propositions. That is, the Propositions offer insight into interdependence theory’s stakeholder engagement and experience-impacting dynamics through the SJ. Next, we discuss pertinent implications that emerge from our research.

Implications and further research

Theoretical implications

Despite its contribution, the CJ literature adopts a limited customer focus, which we—following authors including Kumar and Pansari (2016), Hannay et al. (2020), and Lievens and Blažević (2021)—extended to an omni-stakeholder focus that incorporates not only customers’, but any stakeholder’s, journey with the firm, thus achieving broader, more generalizable journey-based acumen that we expect to boost the firm’s stakeholder relationships and performance (Trianz, 2022). We conceptualized the SJ as “a stakeholder’s trajectory of role-related touchpoints and activities, enacted through stakeholder engagement, that collectively shape the stakeholder experience with the firm,” yielding a wealth of implications for journey-, engagement-, and experience research.

First, by considering their different stakeholders’ journeys (vs. the CJ alone), SJ-implementing firms should be better able to design, manage, or coordinate their respective stakeholders’ journey-based engagement and experience for mutual benefit, yielding the firm’s enhanced stakeholder interactions and relationships, as outlined. For example, stakeholders’ coordinated engagement in open innovation ecosystems has been shown to yield improved collaborative outcomes (Randhawa et al., 2020), in turn lifting firm performance. Building on this insight, we encourage scholars to explore issues including the relative impact of different stakeholders’ engagement, individually and collectively, on specific stakeholders’ journey-based experience. We also recommend future empirical investigation of different stakeholders’ journeys in shaping the firm’s financial, social, and environmental performance (Mish & Scammon, 2010), their success factors, and potential inhibitors. That is, though we envisage SJ-(not merely CJ-) adopting firms to attain superior returns, as outlined, quantification of their respective results remains paramount. Related research questions include:

How do a focal stakeholder’s journey-based role engagement and experience affect the firm’s financial, social, and environmental performance?

What resources, capabilities, and skills are required in transitioning from the CJ to the SJ?

What challenges may be expected in this process, and how can they be overcome?

Relatedly, we propose stakeholder engagement as a pivotal conduit in shaping the SJ’s course, thus extending Demmers et al.’s (2020), Vredeveld and Coulter’s (2019), and Venkatesan’s (2017) CJ-based analyses and raising scholarly awareness of the need to optimally design and manage different stakeholders’ engagement through their respective journeys. A plethora of implications arise from this observation. For example, is stakeholders’ cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioral engagement core in facilitating their respective journeys’ unfolding, and in optimizing the stakeholder experience, in particular contexts? How do changing levels of the identified structural interdependence tenets affect stakeholders’ journey-based engagement, and what is their respective impact on the stakeholder experience?

Moreover, we noted that not only a focal stakeholder’s (own) engagement impacts his/her journey, but that of his/her interaction partner is also likely to do so, and vice versa. For example, Facebook temporarily banned its Australian users from accessing or sharing news stories on its platform due to a dispute over proposed legislation that would compel it to pay news publishers for content, thus impacting these users’ journeys. We, therefore, also advocate the undertaking of future (e.g., empirical) research on the effects of specific interaction partners’ engagement on the focal stakeholder’s engagement and experience, and their interplay (Hollebeek et al., 2022a, b). Related research questions include:

How do stakeholders best position themselves to leverage their partner’s positive journey-based engagement, while insulating themselves against their potential negative engagement, and how does this affect their respective role experience?

How do SJ-based stakeholder engagement/experience pan out under high combined levels of partner- and joint control (e.g., though from an employee’s perspective, a manager has high control over him/her (i.e., high partner control), the manager is also reliant on the employee’s contributions, revealing high joint control)?

Second, we view the SJ to transpire in a network of intersecting journeys that mutually affect one another, as shown in Fig. 1. In this mosaic of traversing ecosystem-based SJs, we explore the effect of interdependence theory’s structural interdependence tenets of stakeholders’ control, covariation of interest, mutuality of dependence, information availability, and temporal journey structure on SJ-based stakeholder engagement and experience, as summarized in the Propositions and shown in Fig. 2. These analyses serve as an important catalyst for further research. For example, though the CJ has been predominantly viewed to comprise a customer’s single role (i.e., purchase) cycle (e.g., Voorhees et al., 2017), we extend the SJ’s scope to a more relational, trans-role cycle perspective (Novak & Hofman, 2019), as outlined, where stakeholders’ role cycles are likely to reveal differing interdependence levels with the firm. For example, while a new supplier’s interdependence with the firm is still forming, that of a long-term vendor will tend to be more established and/or trusting.

These observations also raise myriad implications for future journey research. For example, scholars are encouraged to assess how the identified structural interdependence tenets impact specific stakeholders’ engagement and experience throughout their respective journey-based role cycles (e.g., by comparing key dynamics for new vs. more mature relationships). We also recommend further research on the deployed structural interdependence tenets’ levels relative to one another through stakeholders’ journeys. For example, under what conditions may specific levels of particular stakeholders’ structural interdependence tenets complement or advance (vs. thwart or impede) one another in boosting the firm’s stakeholder relationships and performance?

In Table 5, we offer additional future research avenues organized by our Propositions. For example, P4 states: “A stakeholder’s rising information availability will see his/her more informed engagement in the SJ, increasingly stabilizing the stakeholder experience,” leading us to develop the following sample research question for this proposition in Table 5: “To what extent does information availability inform SJ-based stakeholder engagement, and stabilize the stakeholder experience, for particular stakeholders?” Further investigation of this and related issues is warranted. For example, does high (vs. low) information availability train different stakeholders’ (e.g., customers’/employees’) engagement to an equal (vs. differing) extent through their respective journeys? How may stakeholders’ role engagement and experience differ across roles characterized by higher (vs. lower) informational needs and/or information availability? How might these processes be impacted by stakeholder-perceived information asymmetry (Bergh et al., 2019)?

Managerial implications

This research also yields pertinent managerial implications. Specifically, by understanding, managing, and orchestrating multiple SJs (vs. the CJ alone), firms are expected to boost their stakeholder relationship management and performance outcomes (Mish & Scammon, 2010), as noted. First, in terms of the firm’s financial performance, organizational recognition of multiple stakeholders’ journeys can facilitate the design and development of more coordinated stakeholder interactions and relationships, enabling cost savings and/or enhancing the liquidity of firm assets (Srivastava et al., 1998). For example, by harmonizing their customer- and supplier journeys, companies like Walmart can fine-tune or synchronize their just-in-time-based stock ordering and selling activity, allowing them to rapidly free up cash tied up in inventory.

Second, in terms of the firm’s social performance, companies’ SJ focus stands them in good stead to optimize different stakeholders’ role experience (Chabowski et al., 2011). For example, by understanding workers’ (customers’) role aspirations, challenges, and interactions and by minimizing pain-points through the employee (customer) journey, companies like Google can boost employee (customer) satisfaction, engagement, and retention, respectively, thereby benefiting these stakeholders and the firm (e.g., through reduced hiring/acquisition costs). Moreover, firms’ SJ-based acumen can help them better understand their stakeholders’ (e.g., suppliers’) interactions with others (e.g., strategic partners/customers), offering important strategic insight. For example, car insurance customers’ experience with their car’s service, maintenance, and warranty depends not only on the insurer’s actions, but also on those of the workshop, mechanic, administrator, etc., which SJ mapping can illuminate (Ortbal et al., 2016).

In other words, by visualizing their different stakeholders’ journeys and understanding their respective needs, goals, and dynamics, firms are able to synchronize their journey with that of relevant stakeholders, creating a win–win for those involved (e.g., through smoother SJ-based interactions and relationships; Trianz, 2022). Correspondingly, the above insurance customer’s positive experience results from multiple stakeholders’ (e.g., the distributor’s, manufacturer’s, and the insurance company’s) coordinated journeys. Therefore, those firms that can orchestrate their journey with that of relevant stakeholders are expected to excel. In this vein, BMW has aligned itself with its customers’ journey, which commonly sees clients wishing to replace their car after approximately three years. By instigating a buy-back arrangement that allows customers to sell back their vehicle to the company after this period, these customers’ experience tends receive a boost. In turn, after refurbishing these vehicles, BMW is also able to influence its second-hand customers’ journeys.

Third, in terms of the firm’s environmental performance, companies’ SJ-based acumen helps them assess the impact of their (e.g., resource allocation) decisions and actions on the environment, while also enabling them to shape their stakeholders’ journeys in more sustainable ways (Moretti et al., 2021). For example, by minimizing its pollution and waste and by communicating these values to its customers, The BodyShop helps develop buyers’ demand for responsible cosmetics (Ryan, 2017), thus impacting their CJ and, in turn, also affecting its distributors’, suppliers’, and competitors’ journeys. Therefore, by adopting an SJ focus, firms can raise the extent to which they do good in society (e.g., by meeting customer needs in more resource-efficient ways), while abating any adverse effects, thus contributing to the achievement of their triple bottom-line objectives and building stakeholder trust (Chabowski et al., 2011).

To help achieve the outlined SJ-based stakeholder relationship management and performance gains, we next offer actionable guidelines for SJ-based stakeholder engagement/experience design and management (Teixeira et al., 2017), as organized by the Propositions, in Table 6. For example, addressing stakeholder covariation of interest, P2a and P2b state, respectively: “A stakeholder’s rising coordination (competition) with another will see their more aligned (antagonistic) engagement …in the SJ, increasingly harmonizing (individuating) the… stakeholder experience.” By designing journey-based interactions for coordination (vs. competition), the emergence of any antagonistic effects can be softened or minimized, thus benefiting firm performance, as companies like Shell recognize (see Table 6). For example, we recommend limiting employees’ assigned team members to those that are conducive (vs. detrimental) to their respective role engagement as much as possible (e.g., by matching their personality profiles; De Haan et al., 2016), in turn enhancing their role experience. Overall, we advise firms to adopt relevant SJ prerequisites, guidelines, standards, and checkpoints to lower competition, while also adhering to pertinent institutions (e.g., legislation). For example, many countries have outlawed price fixing, where suppliers collude by overcharging consumers for their products, forcing them to pay elevated prices (Hay & Kelley, 1974), thus illustrating governments’ adoption of legal bounds to protect consumers from firms’ unfair pricing practices and revealing these stakeholders’ competing interests in this regard.

As another example, P3 reads: “A stakeholder’s rising mutuality of dependence with another will see his/her more benevolent engagement toward the other in the SJ, rendering the stakeholder experience increasingly agreeable,” offering further SJ-based stakeholder engagement and -experience design implications (see Table 6). Under high mutuality of dependence, partners rely on each other to a relatively equal degree (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), as noted, stimulating their positive engagement while deterring their negative engagement (e.g., to minimize their partner’s potential retaliation; Li et al., 2018; Scheer et al., 2015). For example, Disney’s strategic partnership with Hewlett-Packard fosters their respective mutuality of dependence, thus producing both parties’ more benevolent engagement toward the other, as illustrated in Table 6.

We recommend boosting partners’ mutuality of dependence where possible, particularly in less interdependent relationships, given its expected stakeholder engagement- and experience-boosting effect. For example, though firms tend to be less reliant, long-term, on contractors (vs. permanent staff), raising these stakeholders’ mutual dependence (e.g., by expanding the contractor’s range of tasks/responsibilities) can be conducive to both stakeholders’ performance (e.g., for the firm: reduced contractor turnover/enhanced operational efficiency; for the contractor: greater income security/income growth). We, however, caution against mutuality of dependence levels at the top end of the spectrum, which can trigger co-dependency (i.e., where one partner constrains or undermines the other; Morgan, 1991) or limited development of stakeholders’ individual identity, capabilities, or performance. We, therefore, advise maintaining stakeholder mutuality of dependence at higher, but not excessive, levels.

Limitations and future research

Firms limiting their focus to the CJ, while ignoring the broader SJ, run a serious performance sub-optimization risk. In this article, we, therefore, conceptualized the SJ and developed a set of interdependence theory-informed Propositions of the SJ, thus placing the SJ on the map for marketers, given its expected role in lifting firm performance. However, despite its contribution, this study is not free from limitations, from which we derive additional research avenues.

First, the purely conceptual nature of our analyses renders a need for their empirical testing and validation, which may – for instance – establish that our proposed associations hold more strongly for some stakeholders (vs. others), or in some contexts (vs. others). For example, P1c reads: “A stakeholder’s rising joint control with another will see his/her more concessional engagement in the SJ, increasingly satisficing the stakeholder experience.” While in some settings, a focal stakeholder may view his/her high joint control with another as agreeable, in others it can be seen as a hindrance, which warrants further attention. Specific research questions include:

What are the factors that give rise to stakeholders’ acceptance (vs. dislike) of specific structural interdependence tenets (e.g., high joint control/mutuality of dependence) across their role (e.g., customer/employee) journeys?

How stable are focal structural interdependence tenets (e.g., joint control) through the SJ and what factors trigger their potential fluctuation?

Second, while we used interdependence theory to inform our analyses, alternate theoretical frames can also be deployed to further explore stakeholders’ journey-based engagement and experience, including organizational justice theory, social exchange theory, network theory, game theory, equity theory, goal-expectation theory, or assemblage theory, to name a few. For example, while social exchange theory can be used to assess stakeholders’ perceived costs/benefits derived from specific SJ-based interactions, equity theory can be deployed to explore the perceived fairness of partners’ respective resource access and contributions, thus affecting journeying stakeholders’ engagement and experience.

Moreover, while assemblage theory can be adopted to examine fluid, multi-functional assemblages of SJ-based stakeholders, tasks, and activities and their respective engagement and experience (Epp & Velagaleti, 2014), further exploration of the theoretical interface of Hillebrand et al.’s (2015) stakeholder marketing perspective and the SJ is also warranted. For example, how might a firm’s prioritization of one stakeholder’s interests affect the unfolding of its other stakeholders’ journeys? Researchers are also encouraged to examine the role of network externalities, which recognize the dependence of stakeholder engagement and experience on the number of stakeholders adopting specific solutions (Frels et al., 2003), and their effect on particular stakeholders’ journeys. For example, in India, Maruti cars command a 49% market share, despite intense competition. Therefore, a customer’s experience of owning a Maruti vehicle depends not only on product quality, but also on the extensive number of other users, enabling convenient access to the brand’s dealer/repair shop network.

Third, the SJ may be viewed as a firm’s multi-stakeholder goal optimization issue, which—when successfully implemented—facilitates a win–win for the firm and its stakeholders, as outlined, thus also meriting further research. Sample questions include:

How do firms optimally align their relevant stakeholders’ journeys for mutual benefit, while minimizing any tension in this regard?

How do firms ensure that their stakeholders’ journeys are consistently progressing in an efficient, effective manner?

How do firms simultaneously optimize their different stakeholders’ journeys?

Relatedly, (how) may firm stakeholders benefit from adopting an SJ perspective (e.g., of their partners’ journeys and their respective activities, goals, and dynamics that may, in turn, impact the former’s journey)? For example, in the case of a delivery delay from Amazon, customers may initially blame the supplier. However, if closer inspection reveals that the delay is due to a lapse in the U.S. Postal Service’s (e.g., pandemic-imposed) mail distribution journey, this helps the customer assess and appropriately resolve the issue (e.g., by locally purchasing a substitute product), thus keeping his/her relationship with Amazon intact.

Fourth, though we assessed interdependence theory’s structural interdependence tenets individually, in practice, these tenets will often jointly affect SJs (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), yielding additional interactional subtleties that warrant further enquiry. For example, coordination featuring high (vs. low) information availability, or high mutuality of dependence coupled with high (vs. low) stakeholder control, are expected to see unique interactional dynamics. We, therefore, encourage the undertaking of further research that explores the concurrent effect of multiple structural interdependence facets on the SJ, thus more holistically depicting journeying stakeholders’ interdependent realities. Relatedly, scrutiny of stakeholders’ potentially changing journey-based interdependence is warranted. For example, despite the initial coordination in Duracell selling its batteries through Amazon, Amazon’s subsequent launch of its Basic (e.g., batteries) private label introduced competition into their relationship, thus impacting these stakeholders’ interdependent journey-based engagement and experience. Therefore, further investigation of the potential drivers of these shifting dynamics, and relevant best practices toward their resolution, is recommended.