History is complicated enough without getting the police involved. But in Poland debates about the darkest event of the 20th century could soon spill over from the seminar room and editorial pages and into the courts, even the prison cells. That’s because a new law, awaiting the president’s signature, would impose a fine or up to three years in jail for anyone found guilty of blaming “the Polish nation” for the Holocaust.

It’s an obvious, nationalistic move by the hard-right Law and Justice party, which rules Poland. But it raises tricky questions, not only about that country but about how to best to safeguard the truth, a question that has become increasingly vexed – even urgent.

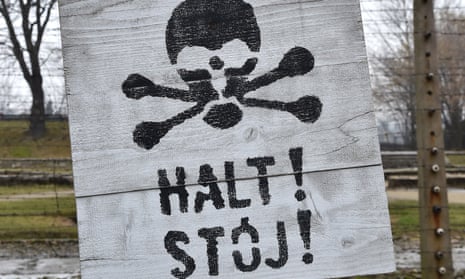

Advocates for the law say their chief target is the phrase “Polish death camps”, which they insist is a slander because Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Sobibór and the rest were established and operated by Nazi Germans, albeit on Polish soil. It was German SS officers, not Poles, who were in charge. Nor were there Poles among the guards and camp personnel, who were often Ukrainian. What’s more, around 2 million non-Jewish Poles were themselves murdered by the Nazis.

That’s all correct: we should speak of Nazi, not Polish, death camps. But the new law goes much wider than this. It seeks to outlaw any suggestion that “the Polish nation”, undefined, was “responsible or co-responsible for Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich”. And here is where things get tricky.

For this seeks to cast Poles as blameless in the slaughter that took place in their midst, to hand them a “certificate of virginity”, in the words of Konstanty Gebert, a journalist for Gazeta Wyborcza whose most recent column dared prosecutors to come after him. “I hereby state,” he wrote, “that numerous members of the Polish nation are co-responsible for certain Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich.”

What he has in mind is, for example, Jedwabne, where in 1941, one half of the town murdered the other half, the non-Jewish Poles turning on their Jewish neighbours – people they’d known for ever, people they had sat next to in school – eventually herding hundreds of them into a barn and burning it to the ground. All told, they murdered 1,600 people. Only seven of the town’s Jews survived.

Jedwabne is a singular case, but of the 3.2 million Jews who were murdered in Poland a sizeable number died at the hands not of Nazi Germans but of their fellow Poles. In Hunt for the Jews, the Polish-born historian Jan Grabowski estimates some 200,000 Jews met their end that way. His meticulous mining of the archive revealed a damning picture. Grabowski found case after case of Jews who had escaped the ghettoes and fled into the forests, only to be handed over to the Nazis by the Polish villagers who found them. Some Poles were coerced into taking part in this hunt for the Jews, but others were eager volunteers. The historian found documents that told how Bronisław Przędział, from the village of Bagienica, found two Jews while searching the woods near his home. After he betrayed them, Przędział demanded his reward from the German occupiers: 2kg of sugar. The rate varied. In some places it was 500 złoty for every Jew. Elsewhere it was two coats, formerly worn by Jews, for each Jew brought in.

Of course there were brave, righteous Poles who risked their lives to harbour Jews. Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust museum has recognised 6,706 Poles for such acts of heroism – more than any other country. But the uncomfortable truth is that the rescuers were the exception, a “tiny, terrorised group who feared, most of all, their own neighbours”, according to Grabowski.

And let’s not forget the Polish Blue Police, who stood guard outside many of the ghettoes and who, according to contemporaneous testimony, were responsible for many, many more Jewish deaths. Under German command, maybe they were in an impossible position; maybe they didn’t yet comprehend the full murderous intent of the Nazi occupiers. The point is, these are precisely the kind of difficult, morally fraught judgments that require honest exploration and open debate. That cannot happen under threat of prosecution. The new law grants an exemption to historians. But who will define who is a historian? Even if Grabowski is immune, what about a journalist who reviews his book?

It’s not hard to see why this has happened. Polish nationalists want Poles to have been the untainted victims of Nazism: it’s hard to admit that too many were willing assistants to genocide. Like almost every nation occupied by the Nazis, and unlike Germany itself, Poland has not yet made a clear-eyed reckoning with its past. It has not fully wrestled with the fact that a Jewish community that once made up 10% of its population, and which was the largest in Europe, has gone, murdered en masse in just over three years. “Poland is not at peace with its Jewish ghosts,” says Gebert. “These are phantom limbs. You amputate the limb and it still hurts.”

Predictably, Israel has sought to hit back with a draft law of its own, making it a crime punishable by jail to deny or diminish the role played by those who connived with the Nazis in persecuting Jews. I understand this impulse, especially when Holocaust denial, or otherwise tormenting Jews with the most painful event in their history, is now such a core component of anti-Jewish racism. Witness this week’s report that antisemitic incidents in the UK rose by over a third, to a record high, with these the words most commonly deployed in anti-Jewish posts on social media: Jews, Holocaust, Hitler, Nazis, Holohoax, gas.

But it is not the right remedy. I am against both the new Polish and Israeli laws for the same reason I oppose any measure criminalising Holocaust denial. Not because I don’t find such denial vile: I do. But because the truth is a plant that cannot be protected by keeping it behind walls, in the shadow of the law. It can thrive only out in the open, where it will be buffeted by argument, to be sure – but where it can also breathe and grow and live.