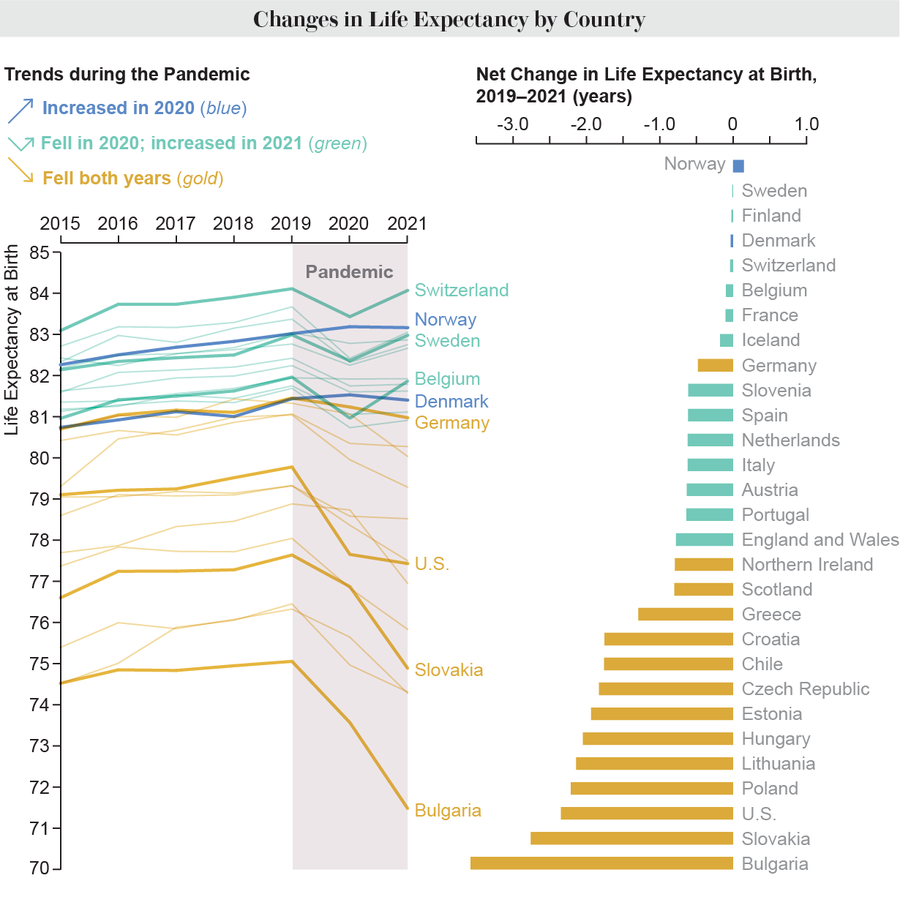

Life expectancy in most countries took a hit during the COVID pandemic. But the U.S. has seen a sharper drop-off than most European countries and Chile—and it still hasn’t recovered.

Worldwide life expectancy was dramatically extended during the past century by decades of progress in medical science and public policy, such as advances in cancer screening and treatment, better prevention and treatment for heart disease, tobacco regulation and safety improvements in the automobile industry. Yet even before the pandemic, U.S. life expectancy had lagged behind that of most other high-income countries.

The pandemic further widened that gap. A study published recently in Nature Human Behaviourestimated life expectancy since 2020 for 29 countries, including most of Europe, the U.S. and Chile. While the majority of these countries experienced a decline in 2020, much of Western Europe bounced back in 2021. But in the U.S. and Eastern Europe, the drop has persisted.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“In the U.S., to have a similar drop in life expectancy from one year to the next like it was in 2020, you need to go back to the time before the Second World War,” says lead study author Jonas Schöley, a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Life Expectancy Changes since COVID-19,” by Jonas Schöley et al., in Nature Human Behaviour. Published online October 17, 2022

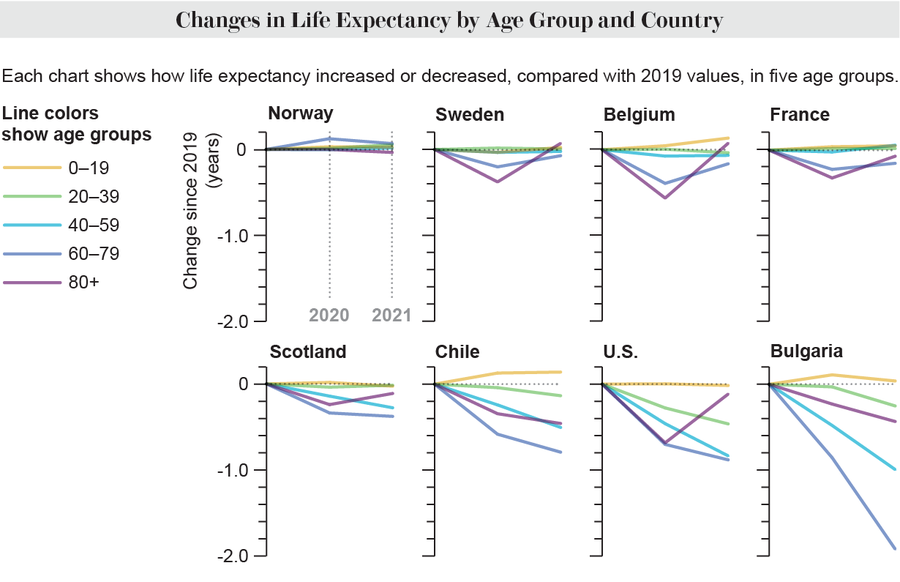

COVID was still the primary cause of excess deaths in the U.S., Europe and Chile in 2021, according to the study authors. The rapidly developed COVID vaccines clearly saved lives, however: life expectancy declines were negatively correlated with vaccination rates. And the benefits were most pronounced among the oldest age groups. The pattern of excess mortality—a measure of how many more people die in a year than average—shifted to younger age groups in 2021, compared with 2020.

“The shift toward higher mortality in younger ages in 2021 reflects both the successful vaccination of the majority of older adults who were most at risk of dying from COVID-19 and the relatively low uptake of vaccination in younger adults,” says Theresa Andrasfay, a postdoctoral scholar in gerontology at the University of Southern California, who was not involved in the new study.

Countries that recovered from their 2020 life expectancy shocks did so by lowering mortality in older age groups. For example, Belgium suffered terribly in 2020; some COVID patients there had to be flown to other parts of Europe for treatment, Schöley says. But in 2021 Belgium was able to normalize death rates among people age 80 and older, as well as among people ages 60 to 80, without increasing mortality among younger age groups. By contrast, the U.S. has only restored prepandemic mortality rates in people age 80 and up. All other age groups in the nation have seen mortality rates increase.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Life Expectancy Changes since COVID-19,” by Jonas Schöley et al., in Nature Human Behaviour. Published online October 17, 2022

The U.S. stood out among the countries studied for its deep and persistent drop in life expectancy. Amid its disjointed and inadequate pandemic response, the death toll has soared to more than a million people and counting. Other factors have also played a role in the more persistent decline seen in this country—drug overdoses now account for close to 100,000 deaths per year—a large majority caused by opioids. And the losses haven’t been felt evenly: Indigenous, Black and Latino populations in the U.S. experienced greater drops in life expectancy than other demographic groups.

“There is a confluence of factors contributing to greater and more persistent losses in the U.S., including a less robust national response to the pandemic in 2020, lower adherence to social distancing guidelines, a higher prevalence of underlying conditions and lower vaccination,” Andrasfay says. “The U.S. stood out in terms of having more deaths from causes other than COVID-19, indicating that the U.S. did a worse job containing the impacts of the pandemic on the broader health care system.”

Schöley agrees. “What happened in the U.S., as far as we can tell right now, is that they had to deal with two health crises at the same time,” he says. In 2019 “life expectancy was in a fragile balance in the U.S. It was still increasing overall due to declines in mortality [from] cancer and cardiovascular diseases at all the ages. But at the same time, you had a worsening opioid crisis, deaths of despair, deaths due to drug intake.” And these trends only accelerated in 2020 when COVID emerged, he says.

The closest European comparison to the U.S. might be Scotland, which is confronting its own opioid crisis, Schöley says. Countries in Eastern Europe also saw persistent declines in life expectancy in 2021. But only Bulgaria and Slovakia reported greater net declines than the U.S. Before the pandemic, Eastern European countries had a lower life expectancy than Western European ones—although it had been catching up. “But the pandemic has, in some sense, interrupted that very dramatically,” says the new study’s co-author Ridhi Kashyap, a professor of demography at the University of Oxford.

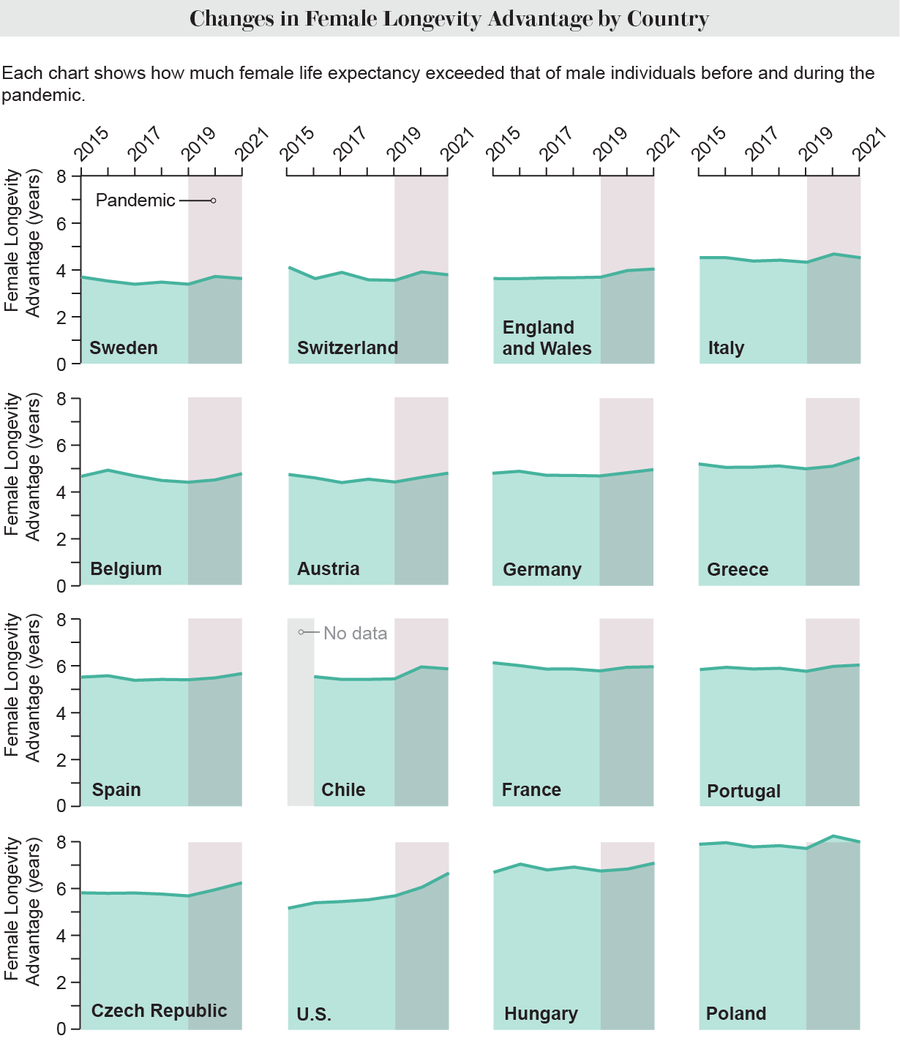

The study also revealed a widening gap between male and female life expectancy. Globally, women tend to outlive men for various reasons—a phenomenon known as female advantage. The gap in had been narrowing before the pandemic struck, but COVID increased the female advantage in most of the countries studied, and the U.S. had the largest increase. In general, COVID is more deadly in men than women, and other causes of excess death, such as opioid overdoses, also disproportionately occur in men.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Life Expectancy Changes since COVID-19,” by Jonas Schöley et al., in Nature Human Behaviour. Published online October 17, 2022

The study has some limitations. It didn’t include countries such as Japan and New Zealand, which took unusually strict containment measures during the pandemic, Andrasfay says. And it only included middle- and high-income countries that had high-quality data. “The impacts of the pandemic are likely to be much greater in lower-income countries,” she says.