-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

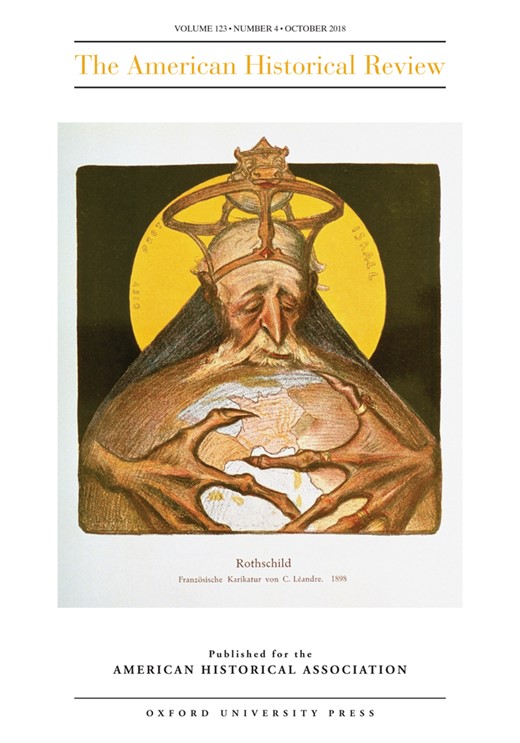

Scott Ury, Strange Bedfellows? Anti-Semitism, Zionism, and the Fate of “the Jews”, The American Historical Review, Volume 123, Issue 4, October 2018, Pages 1151–1171, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhy030

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article examines the different ways that anti-Semitism and Zionism have confronted and influenced one another through a tension-filled dialectic that is simultaneously self-evident and counterintuitive. The essay begins with a discussion of the central place of anti-Semitism in canonical Zionist texts such as Leon Pinsker’s Auto-Emancipation and Theodor Herzl’s The Jewish State. Both Pinsker and Herzl believed that anti-Semitism was a permanent or immovable force, and this interpretation of anti-Semitism led them to embrace, if not create, political Zionism. The following section analyzes the works of two émigré scholars, Salo W. Baron and Hannah Arendt, who wrote fervently about the need to avoid “the lachrymose conception of Jewish history” and the school of “eternal antisemitism,” and to focus instead on the actions that Jews undertook as historical actors in specific contexts. Despite their influence, the study of anti-Semitism over the past two generations has returned to a perspective that is strikingly similar to traditional Zionist interpretations. The penultimate section of this piece delineates how two historians in Israel, Shmuel Ettinger and Robert S. Wistrich, reinforced and reaffirmed key aspects in this interpretive paradigm, including anti-Semitism’s unique nature as “the longest hatred,” the recurrent abandonment of the Jews by their neighbors, and the strange, befuddling, and problematic relationship between anti-Semitism and Zionism. The essay ends with a discussion of the different ways that anti-Semitism and Zionism continue to interact with and influence one another, in particular through current debates in and between the public and the scholarly realms regarding “the new anti-Semitism.” The article concludes by suggesting that scholars return to the contextual-comparative approach to the study of anti-Semitism as part of larger efforts to separate and insulate academic research on the topic from contemporary political considerations.

In an elegant essay on Jewish politics in interwar Poland published some thirty years ago, the late Ezra Mendelsohn wrote eloquently about the problematic relationship between anti-Semitism and one of the more successful variants of modern Jewish politics, Zionism. Surveying the Jewish and Polish political landscapes of the time, Mendelsohn noted how Polish national and even anti-Semitic leaders and their Jewish counterparts often ended up as strange bedfellows—sharing a common intellectual, conceptual, and political universe. Whether supporting the view that Poland was a society composed of different nations, advocating for the mass migration of Jews from Poland, or highlighting the link between discrimination and creativity, Zionist culture and politics seemed to flourish in a time and place where Jews were confronted with political, social, and governmental hostility, which many summarize to this day with the catchall term under discussion in this roundtable, “anti-Semitism.”1

By pointing to the common language, politics, and worldviews shared by both Polish nationalists and Zionist leaders, Mendelsohn was highlighting the longstanding, befuddling, and at times problematic connection between Zionism and anti-Semitism, one that continues to influence dominant conceptions and definitions of anti-Semitism and research on the subject to this day. In many cases, contemporary analyses of anti-Semitism remain deeply indebted to key concepts and paradigms that early Zionist thinkers developed in response to the appearance of political anti-Semitism in turn-of-the-century Eastern and Central Europe. The dialectical relationship between these two concepts and their accompanying camps helps explain why academic interventions on the topic are often fraught with sociological and political considerations and reverberations.2 It also points to one of the biggest problems facing the study of anti-Semitism today: its ongoing, seemingly inescapable connection to public affairs and the extent to which contemporary political concerns, in particular those regarding Zionism and the State of Israel, influence and shape the way that many scholars frame, interpret, and research anti-Semitism. While no academic field is free of contemporary social or political considerations, the study of anti-Semitism has a long, tension-filled, and problematic history of attempting to serve simultaneously two distinct albeit related masters. Over time, anti-Semitism’s curious dual role—as both the topic of heated public debates and the subject of ostensibly neutral academic research—has repeatedly influenced the various and changing conceptualizations, definitions, and understandings of the phenomenon, as well as the contentious nature of the field today and potential plans for resolving the current academic and intellectual impasse.

The kaleidoscope of negotiations and (mis)interpretations between past and present as they unfold and intersect in both the world of scholarship and the realm of politics is in no way unique to the study of anti-Semitism. Definitive scholars such as Michel Foucault and Hayden White have raised a series of questions regarding the extent to which history and other academic disciplines can render an objective or even a realistic account of the past, as well as the role that an author’s current state plays—both consciously and subconsciously—in the different ways in which the past is framed, understood, and written as history.3 Together, these works have encouraged generations of scholars to reevaluate their understanding of the nature of historical narratives as well as the concept of historical truth. Many of the same questions regarding the possibilities and limits of academic research lie at the very core of the heated, at times vituperative, debates among scholars and community members regarding the study of anti-Semitism as well as the underlying tension between the academic study of the phenomenon and political campaigns against anti-Semitism. Scholars repeatedly wonder about the extent to which contemporary concerns influence academic and research agendas as well as the cyclical, seemingly inescapable relationship between hatred or fear of “the Jews,” on the one hand, and Jewish communal organization and politics, on the other.4 As with many other emotionally charged fields of scholarly inquiry with far-reaching implications, it remains unclear whether anti-Semitism can (or should) be studied in a detached academic fashion, and if not, what observers are to make of this academic minefield fraught with political overtones, existential ramifications, and emotional responses. As academics working and writing in a time that seems to be dictated increasingly by a concern with the potential appeal and consumption of scholarly works, we all want the study of history, and especially our own historical studies, to matter. But what are we to do when history seems to matter too much?

The connection between anti-Semitism and Zionism did not originate in interwar Poland, but in fact can be traced back to the parallel development of these two concepts in late-nineteenth-century Eastern and Central Europe.5 Thus one of the earliest tracts of Zionist political thought, Auto-Emancipation by Leon (Yehuda Leib) Pinsker, was structured around the thesis that anti-Semitism—or Judeophobia, as Pinsker referred to it—was an indelible psychological disorder that was transformed, over time, to a social disease, and that the only solution available for “the Jews” was to emancipate themselves in an act of collective “self-liberation.”6 The immediate impetus for Pinsker’s manifesto, which was originally published some two years after the German journalist Wilhelm Marr popularized the term “anti-Semitism,” was the wave of anti-Jewish violence (pogroms) that swept the southwestern provinces of the Russian Empire in 1881–1882.7 Most scholarly accounts of Pinsker’s volte-face from his earlier support for Jewish integration to his fervent advocacy for Jewish nationalism present his 1882 treatise as a moment of Zionist revelation, if not epiphany.8 Spirited in its nature, convincing in its rhetoric, and seductive in its logic, Pinsker’s pamphlet would go on to attain canonical status in Zionist circles as it bound Jewish nationalism to anti-Semitism through a series of fundamental axioms. Moreover, while influential Zionist thinkers and leaders such as Ahad Ha’am, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, and David Ben-Gurion would develop their own versions of Zionism that differed significantly from Pinsker’s early clarion call, the central tenets of Pinsker’s German-language pamphlet are critical for understanding contemporary conceptualizations of anti-Semitism and its longstanding connection to Zionist politics and thought.9

The first of Pinsker’s main points was that Enlightenment designs for the integration of the Jews into European society had failed, miserably. Overturning a century of Enlightenment ideology as well as much of his own public activity in Odessa, Pinsker maintained that no degree of cultural accommodation or social adaptation would ensure the Jews’ entrance and acceptance into their surrounding societies as equals. Alluding to traditional religious themes of dispersion and punishment, Pinsker maintained that the Jews “are everywhere as guests, and nowhere at home”; and that “since the Jew is nowhere at home, nowhere regarded as a native, he remains an alien everywhere.”10

Moreover, as a result of the Jews’ state of geographic dispersion and social liminality, “the world saw in this people the uncanny form of one of the dead walking among the living.”11 Over time, this “fear of the Jewish ghost” would lead to the development of what Pinsker referred to as Judeophobia.12 Trained as a physician, Pinsker understood Judeophobia to be “a form of demonopathy” that had been transformed from “a psychic aberration” into a hereditary social disease that would then be “handed down and strengthened for generations and centuries.”13 Over time, Judeophobia had grown to become nothing less than a “blind natural force.”14 As Enlightenment visions of Jewish integration collapsed and as non-Jewish Europeans repeatedly turned their backs on their Jewish neighbors, Jews had little choice but to “reconcile ourselves, once and for all, to the idea that the other nations, by reason of their eternal, natural antagonism, will forever reject us.”15

Confronted with the “blind natural force” of Judeophobia, Pinsker implored his readers to embrace their inner Jewish nation. Dismissing European liberalism as yet another false (Jewish) Messiah, he demanded: “We must seek our honour and our salvation not in illusory self-deceptions, but in the restoration of a national bond of union.”16 Once developed, this national consciousness would lead Jews to the inevitable conclusion that they “must have a home, if not a country of our own.”17 And so Leon Pinsker, the progenitor of political Zionism, would declare in his 1882 Zionist treatise that “Judaism and Anti-Semitism passed for centuries through history as inseparable companions. Like the Jewish people, the real wandering Jew, Anti-Semitism, too, seems as if it would never die.”18

A generation later, Theodor Herzl’s encounters with social, political, and popular anti-Semitism—in Vienna, where he witnessed the rise of Karl Lueger, and in Paris during the Dreyfus Affair—led him to a set of conclusions that were strikingly similar to Pinsker’s. Thus, while Herzl had earlier toyed with various integrationist solutions to “the Jewish Question”—including mass conversion to Catholicism—the rising tide of political anti-Semitism and the ambivalent response of many of his contemporaries similarly convinced him of the indelible nature of anti-Semitism and the illusory prospects for Jewish integration into European society.19 As Herzl would caution in an 1895 letter to Albert Rothschild, “I consider the Jewish Question an extremely serious matter. Anyone who thinks that agitation against the Jews is a passing fad is seriously mistaken. For profound reasons it is bound to get worse and worse.”20 Returning to this theme in his 1896 political treatise The Jewish State, Herzl asked rhetorically, “We cannot get the better of Anti-Semitism by any of these methods. It cannot die out so long as its causes are not removed. Are they removable?”21 Soon after coming to these conclusions regarding the nature of anti-Semitism, Herzl not only embraced Zionism but advanced the movement significantly by convening the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897.22

However, while Pinsker’s dystopic interpretation of history bound “the Jews” to a fate of enmity and isolation, Herzl’s hubris and faith in modern technology led him to propose “a modern solution of the Jewish Question,” as the subtitle of The Jewish State claimed.23 According to Herzl, anti-Semitism would serve as nothing less than the very motor that would generate the imminent transformation and ultimate regeneration of “the Jews.” Parallel to biblical accounts regarding the Israelites’ deliverance from slavery in ancient Egypt, the trials of Jewish pain and suffering across turn-of-the-century Europe would lead to a new, hitherto unknown form of Jewish pleasure: a modern state.

Everything depends on our propelling force. And what is our propelling force? The misery of the Jews. Who would venture to deny its existence? . . . Everybody is familiar with the phenomenon of steam-power, generated by boiling water, lifting the kettle-lid. Such tea-kettle phenomena are the attempts of Zionists and of kindred associations to check Anti-Semitism. Now I believe that this power, if rightly employed, is powerful enough to propel a large engine and to despatch passengers and goods: the engine having whatever form men may choose to give it.24

In his ostensibly private correspondence, Herzl was even more explicit regarding the connection between anti-Semitism and his own Jewishness as well as his recent turn to Zionism. In an 1895 letter to Moritz Güdemann, the chief rabbi of Vienna, Herzl confided: “I was indifferent to my Jewishness; let us say that it was beneath the level of my awareness. But just as anti-Semitism forces the half-hearted, cowardly, and self-seeking Jews into the arms of Christianity, it powerfully forced my Jewishness to the surface.”25 Like Pinsker, Herzl came to view anti-Semitism as a seemingly natural, potentially unstoppable force. However, while it might adversely affect the social and economic status of individual Jews, it also had the potential to advance infinitely higher goals, including the alleviation of the seemingly interminable “sufferings of the Jews.”26

Anti-Semitism not only “forced [Herzl’s] Jewishness to the surface” and led him to embrace Zionism, but in doing so, it also encouraged him to adopt a radically new understanding of “the Jews,” one that redefined and reconstituted them as “a people—one people.”27 Echoing comments by Pinsker and others regarding the impact of anti-Semitism on the nature and reconceptualization of “the Jews,” Herzl would proclaim a central mantra of his newfound political faith: “We are one people—our enemies have made us one in our despite . . . Distress binds us together, and, thus united, we suddenly discover our strength.”28

For both advocates of anti-Semitism and early Zionist leaders, the two opposing ideologies and their respective camps repeatedly met at moments of confrontation where both anti-Semitism and “the Jewish Question” were understood as part of Europe’s “national question,” and “the Jews” were, in turn, deemed to be a distinct and separate nation.29 Thus, despite the vast differences between them, representatives of political Zionism and advocates of anti-Semitism repeatedly faced and influenced one another. Moreover, as Mendelsohn noted in regard to interwar Poland, these moments of confrontation were grounded in and helped reinforce a common set of assumptions regarding the very nature of “the Jews,” their relationship to their surrounding societies, and, ultimately, their fate as a collective polity.30 Acutely aware of these peculiar, if not counterintuitive, moments of intersection and patterns of influence, Herzl confessed his own anxieties regarding the potentially embarrassing relationship between anti-Semitism and Zionism. “It might more reasonably be objected that I am giving a handle to Anti-Semitism when I say we are a people—one people.”31

While key turn-of-the-century thinkers helped create a paradigm for understanding anti-Semitism and its relationship to Zionism, Jewish scholars of the following generations in North America (many of whom were transplants from these same regions) often came to radically different conclusions regarding the nature of anti-Semitism, its place in “the history of the Jews,” and its implications regarding the fate of “the Jews.” These differences represent not only many of the changes associated with migration from East-Central Europe to America, but also the progressive integration of Jews and Jewish studies into American society and academia. No longer grounded in minority apologetics, scholars of Jewish studies were (relatively) free to explore aspects of Jewish social, religious, and political histories that revolved around topics other than anti-Jewish animus, discrimination, and segregation. Few scholars embody these intellectual transformations more than Salo Wittmayer Baron, the doyen of Jewish history in North America. Born in Galicia, Baron immigrated to the United States in 1926, where he became a professor of Jewish history at Columbia University. Throughout his illustrious career, Baron argued against the tendency of scholars and community members to view the long course of Jewish history through the lens of persecution, suffering, and anti-Semitism.32 He repeatedly urged his readers and students to focus on the achievements of Jewish society and culture and not dwell on what he referred to as “the lachrymose conception of Jewish history.”33 Looking back on his long career in 1963, Baron noted: “All my life I have been struggling against the hitherto dominant ‘lachrymose conception of Jewish history’ . . . because I have felt that an overemphasis on Jewish sufferings distorted the total picture of the Jewish historic evolution and, at the same time, badly served a generation which had become impatient with the nightmare of endless persecutions and massacres.”34

In addition to warping the historical record, “the lachrymose conception of Jewish history” also influenced contemporary interpretations and definitions of “the Jews.” On the one hand, “modern anti-Semitic movements” advocated “racial anti-Semitism” to validate “the permanence and immutability of the Jewish group by virtue of blood and descent regardless of individual religious beliefs and observances.”35 At the same time, Baron voiced concern regarding those Jewish groups, including representatives of both Reform Judaism and Zionism, who embraced an “exaggerated historical picture” characterized by “extreme wretchedness.” In the case of Zionism, these efforts were part of larger designs “to reject the Diaspora in toto, on the grounds that a ‘normal life’ could not be led by Jewry elsewhere than on its own soil.”36 While Baron was never one to dismiss anti-Semitism and supported Zionism and other forms of Jewish nationalism over the years, he was fundamentally opposed to using anti-Semitism as an intellectual tool to interpret, define, and bind the nature, history, and fate of the Jews.37 A firm believer that Jewish society, culture, and community could be developed fully in a variety of different settings, Baron concluded his seminal 1928 essay “Ghetto and Emancipation” by declaring: “Surely it is time to break with the lachrymose theory.”38

Although Hannah Arendt’s understanding of the intersection between European history, Jewish society, and anti-Semitism was radically different from Baron’s, the two émigré scholars shared many assumptions regarding both the history of anti-Semitism and its influence on prevailing interpretations of Jewish history and society.39 Arendt’s brilliant study The Origins of Totalitarianism examined the collapse of European society alongside the intersection of anti-Semitism and imperialism within the rise of totalitarian systems. In contrast to the analyses of anti-Semitism detailed by Pinsker and Herzl, Arendt maintained that anti-Semitism was neither an eternal death sentence for the Jews nor an indelible stain for Europe, but rather something dynamic and contextually specific. Like her longtime colleague Baron, Arendt found the lachrymose conception of Jewish history and the accompanying school of “eternal antisemitism” to be utterly unconvincing.40 Her critique of such approaches to the study of anti-Semitism and its place in the history of the Jews was scathing:

The scapegoat explanation therefore remains one of the principal attempts to escape the seriousness of antisemitism and the significance of the fact that the Jews were driven into the storm center of events. Equally widespread is the opposite doctrine of an “eternal antisemitism” in which Jew-hatred is a normal and natural reaction to which history gives only more or less opportunity. Outbursts need no special explanation because they are natural consequences of an eternal problem.41

Deriding the school of “eternal antisemitism” as nothing less than “fallacious,” Arendt insisted on grounding the study of anti-Semitism amid specific historical events, contexts, and agents.42 “Modern antisemitism must be seen in the more general framework of the development of the nation-state, and at the same time its source must be found in certain aspects of Jewish history,” she would note with her own unique mixture of insight and iconoclasm.43

While Arendt’s understanding of anti-Semitism challenged traditional Zionist interpretations of the phenomenon, her conclusions regarding the connection between anti-Semitism and Zionism echoed many of the observations made by Pinsker, Herzl, and other early Zionist thinkers. Thus, she noted, “The only direct, unadulterated consequence of nineteenth-century antisemitic movements was not Nazism but, on the contrary, Zionism, which . . . was a kind of counterideology, the ‘answer’ to antisemitism.”44 From Arendt’s vantage point, the two ideologies repeatedly reaffirmed one another’s existence through an ongoing dialectic that had far-reaching historical, social, and political ramifications. However, unlike Pinsker or Herzl (but similar to Baron), Arendt actually reversed the causal relationship between these two conflicting ideologies by maintaining that it was often nationally oriented Jews who insisted on the eternal nature of anti-Semitism so that it could be used to bolster their own interpretation of “the Jews” as a separate, eternal people. “Jews concerned with the survival of their people would, in a curious desperate misinterpretation, hit on the consoling idea that antisemitism, after all, might be an excellent means for keeping the people together, so that the assumption of eternal antisemitism would even imply an eternal guarantee of Jewish existence.”45 In Arendt’s postwar reassessment of humanity’s fall, anti-Semitism had passed from being a threat to the Jews’ existence to a factor that would help maintain social cohesion and ensure “the survival of their people.”46 Most importantly, despite the vast differences between Arendt’s interpretation of history and those espoused by Pinsker and Herzl, anti-Semitism and Zionism were once again bound to one another through a dialectical process that not only determined their nature as binary forces but, in doing so, helped define and solidify the existence of two separate, ostensibly self-contained ideologies as well as their respective communities of faith and fate.

While Arendt’s attempts to demystify anti-Semitism contributed much to the vituperative criticism of her and her work by Jewish thinkers and communal representatives, her efforts to integrate the study of anti-Semitism into wider analytical frameworks were profoundly influential and reflect the larger transformation of the study of anti-Semitism into a viable topic of scholarly research in American academia.47 As Jack Jacobs and Jonathan Judaken have both shown, a series of key studies were composed in the postwar era that addressed anti-Semitism from an academic rather than an ethnonational or communal perspective.48 Throughout this period of reflection and penitence, leading figures such as Theodor Adorno and Bruno Bettelheim asked what anti-Semitism could teach scholars and readers about the nature of prejudice, the course of modernity, and the potential amelioration of inter-group conflicts.49 Thus, while many of these studies may have originated with the trauma of war and the long shadow of anti-Semitism rising above the killing fields and death camps across the vast terrain of East-Central Europe, they often examined these issues within broader historical, sociological, and political contexts.50 As Max Horkheimer and Samuel Flowerman noted in their foreword to the influential book series Studies in Prejudice, “Prejudice is one of the problems of our times for which everyone has a theory but no one an answer.”51 In these and other studies, scholars from a range of academic disciplines were concerned with understanding a broad set of social and political problems, including prejudice and racism, and consciously refrained from examining one specific brand of hatred, anti-Semitism, directed against the members of one particular group, “the Jews.”

Despite these and other attempts to integrate the study of anti-Semitism into larger scholarly frameworks, research over the past two generations has, to a great extent, returned to a position strikingly similar to the one advanced by Pinsker, Herzl, and other early advocates of a Zionist solution to “the Jewish Question.”52 One of the more influential figures in this academic transition was the Kiev-born Israeli scholar of Jewish history Shmuel Ettinger.53 Although he wrote on a wide range of topics, Ettinger published a number of pieces that revolved around and reaffirmed key themes in the traditional Zionist interpretation of anti-Semitism, such as the long, continuous history of anti-Jewish animus, the repeated abandonment of the Jews by their European neighbors, and the recurrent link between Zionism and anti-Semitism.54 A revered figure in Israeli academia, Ettinger shaped the way in which generations of scholars understood, taught, and wrote about anti-Semitism.55

Openly positioning himself in contradistinction to Arendt, Adorno, and other prominent (Jewish) thinkers in postwar America, Ettinger openly attacked those “psychologists, sociologists and historians who view anti-Judaism (sinat yisrael) as a phenomenon with wider, general implications, including several of these scholars who [view it as] one with universal implications.”56 Like many other advocates of the Jerusalem school of Jewish history, Ettinger believed that the fundamental sin of these studies was that “from the very beginning, they turn the Jews into a minor if not a random factor” in the course of history, and that they were not at all concerned with how “to evaluate it [anti-Semitism] as a factor in the history of the Jews.”57 He spared no punches in deriding those comparative or universal approaches to the study of anti-Semitism that “completely miss the point.”58 In an essay on the connection between anti-Semitism and the Holocaust, Ettinger clarified his position regarding the historically continuous and therefore unique nature of anti-Semitism as well as its central place in the longue durée of Jewish history. “The Holocaust is deeply connected to the phenomenon of anti-Semitism, which accompanied the Jewish people over its history for thousands of years; this hatred is a unique phenomenon in the history of relations between national and religious communities.”59 For Ettinger and many other Israeli scholars of his generation, anti-Semitism was as historically continuous and as unique as the people that it confronted and helped shape: “the Jewish people.”60 Lastly, as a unique phenomenon, anti-Semitism could not be compared to any other form of hatred directed at members of any given minority group.61

Many of Ettinger’s articles on anti-Semitism were composed in the heat of the Cold War, and, as a result, they were deeply informed by his growing preoccupation with Soviet Jewry.62 In a series of essays on the topic that liberally mixed academic research and political concerns, Ettinger underscored the “historical continuity of anti-Semitism” that dated back to early Christianity.63 Pointing to developments in the Soviet Union, he noted that “Soviet anti-Jewish propaganda relies on the classical antisemitic motifs derived from nineteenth century Russian antisemitic literature, European antisemitic literature and a flavoring of elements of current affairs.”64 Moreover, despite periods of tolerance, Ettinger warned (much like Pinsker and Herzl) that anti-Semitism was “deeply rooted in the Russian heritage” and that it could easily “be activated among the various strata of society.”65 Encapsulating the “eternal antisemitism” school of thought that Arendt had ridiculed and dismissed, Ettinger believed that anti-Semitism was a historical constant that had accompanied and shaped the Jews over the course of their long, continuous history.

Ettinger’s angry critique of the Soviet Union was exacerbated by a personal sense of betrayal.66 As a young émigré student in Jerusalem in the 1930s, Ettinger was a dedicated member of the Palestine Communist Party, and some scholars maintain that his research on the Soviet Union should be seen as part of his own personal path from Soviet darkness to Zionist light.67 Throughout these studies, he presented anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union as proof of the corrupt nature of Soviet society. Writing about the Holocaust as well as recurrent anxieties regarding social and political abandonment, he noted: “The Holocaust years uncovered the bitter truth about the Soviet ‘brotherhood of peoples.’”68 As part of these efforts to discredit the Soviet Union further, he also highlighted many of the underlying similarities between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.69

Little seemed to expose the Soviet Union’s true nature and fundamental hypocrisy more than the regime’s anti-Zionist campaigns. According to Ettinger, anti-Zionism in the Soviet Union after the Arab-Israeli War of 1967 was little more than a poorly constructed fig leaf designed to camouflage the deep undercurrent of anti-Semitism that stained and polluted European history and society.70 Writing in 1988, he argued that “[t]he main expression of antisemitism in the USSR today is through a propaganda campaign which can be called ‘The Struggle Against Zionism.’”71 Nor was this phenomenon limited to the Soviet Union. In a caustic Hebrew essay titled “Anti-Semitism and Anti-Zionism among Youth in the Western World” that was published in 1985 by the Israeli Ministry of Education and Culture, Ettinger claimed that hostility toward Israel on the European Left was proof of the long, irrepressible, and potentially indelible nature of anti-Semitism, as well as the collapse of European liberalism.72 Pointing his finger at members of the European Left, Ettinger maintained: “A new situation has arisen that integrates anti-Semitic instincts and tendencies that were temporarily suppressed due to the Holocaust and liberal education into the so-called war against racism and anti-Zionism.”73 Although their works were separated by more than a hundred years, two world wars, the rise of the Soviet Union, the creation of the State of Israel, and the Cold War, Shmuel Ettinger and Leon Pinsker were bound by a common language and worldview.74

While some might be tempted to dismiss Ettinger’s work as eclectic and polemical, many of the points he raised were central to the work of the most prolific scholar of anti-Semitism over the past few decades, Robert S. Wistrich.75 Through a series of lengthy studies, Wistrich helped reaffirm and refine traditional Zionist interpretations of anti-Semitism and its relationship to the course of Jewish history and the state of contemporary Jewry. In fact, Wistrich is so influential that many scholars embrace much of his oeuvre without questioning its underlying assumptions or their scholarly ramifications.76 More than any other scholar, Wistrich has helped move the study of anti-Semitism away from the contextual or comparative framework advocated by Arendt and Baron and return it to a more traditional Zionist interpretation of Jewish history, society, and fate.

Much like Pinsker and Herzl (as well as Ettinger), Wistrich maintained that anti-Semitism is no less than “the longest hatred,” one that originated in ancient times and has continued, albeit in different permutations, to the present, and whose demise seems far from imminent.77 Turning to these and other ostensibly unique aspects of anti-Semitism, Wistrich noted in his 2010 tome A Lethal Obsession: Anti-Semitism from Antiquity to Global Jihad—whose title embraces his overall argument—that “[t]here has been no hatred in Western Christian civilization more persistent and enduring than that directed against the Jews. Though the form and timing that outbursts of anti-Jewish persecution have taken throughout the ages have varied, the basic patterns of prejudice have remained remarkably consistent.”78 Not only has anti-Semitism continued unabated from ancient times to today, but its historical longevity and continuity demonstrate how impervious it has proven to various social or political interventions. Referring to key Zionist thinkers, Wistrich notes that “[m]ost Zionists have regarded anti-Semitism as an ineradicable disease that cannot be corrected merely through education, reason, or enlightenment, let alone assimilation.”79 While he may have earlier cautioned against such interpretative strategies, many of Wistrich’s more recent studies present anti-Semitism as a historically continuous, unique, and potentially ineradicable phenomenon.80 For Wistrich, the past was ever present.

Another point made by both early Zionist thinkers and Wistrich is the sense of abandonment or betrayal by former allies, particularly those on what Wistrich and others refer to rather loosely as “the Left.” Wistrich’s 2012 volume From Ambivalence to Betrayal: The Left, the Jews, and Israel discusses at length the ostensible hypocrisy of the European, North American, and even Israeli Left regarding anti-Semitism. Focusing on how “the Left” has betrayed “the Jews” through its support for the Palestinian cause and accompanying calls for the ostensible dissolution—or at the very least the radical reconstruction—of “the Jewish State” of Israel, Wistrich’s rhetoric is merciless, his arguments polemical, and his anger visceral.81 “The advocacy by a broad section of the contemporary Left of such defamatory propositions is a betrayal of its own egalitarian principles and supposed respect for democratic values.”82 Here, as well, the condemnation by Wistrich and others of “the Left” and its supposed hypocrisy mirrors the frustration that Pinsker, Herzl, and others felt in turn-of-the-century Europe as well as Ettinger’s longing for interethnic solidarity within the framework of interwar communism.83

A third point that Pinsker and Herzl share with Ettinger and Wistrich is the link between Zionism and a growing anxiety about, if not a fear of, anti-Semitism. As is true in many other cases, the exact causal relationship between the chicken and the egg in this vicious circle is nearly impossible to ascertain. That said, the same tension-filled dialectic between anti-Semitism and Zionism that shaped the observations and conclusions of early Zionist leaders was critical to Wistrich’s thinking on these points. For Wistrich and many other observers, this connection is best illustrated by what is often referred to as the “new anti-Semitism” and the manner in which this latest iteration of “the longest hatred” focuses its bile on the State of Israel in its role as “the collective Jew.”84 Turning his attention to contemporary debates regarding Israel, Wistrich declares that “the ‘new’ antisemitism involves the denial of the rights of the Jewish people to live as an equal member within the family of nations. In that sense contemporary antisemitism above all targets Israel as the ‘collective Jew’ among the nations.”85 In a dramatic case of ideological transposition, many supporters of Zionism and those advocating the “new anti-Semitism” essentially agree that the State of Israel serves as the primary representative of all Jews across the globe, regardless of their political leanings, cultural affiliations, or geographic location.86 As Wistrich notes in A Lethal Obsession, “Anti-Zionism has never been completely identical to anti-Semitism, but some thirty years ago it began to fully crystallize as its offspring and heir. At times it even seems like its Siamese twin.”87 Try as each may to disavow and disown the other, anti-Semitism and Zionism continue to conflict, contradict, and influence one another as a strange set of political and academic bedfellows.88

These developments raise a myriad of puzzling questions. Why has the traditional Zionist interpretation of Jewish history, society, and fate returned over the past two generations to become the dominant academic and public framework for researching, studying, and explaining anti-Semitism? How has the resurgence of this specific intellectual paradigm helped shape, define, and determine the contours and development of this particular scholarly field and accompanying public discussions over the past few decades? And can scholars create and make room for alternative interpretations of anti-Jewish prejudice and hostilities that are free of contemporary political pressures?

Observers and critics of the “new anti-Semitism” will maintain that the proof of the pudding is in the eating.89 Pointing to ongoing hostilities and animosities in the Middle East as well as their troubling aftereffects across Europe, America, and elsewhere, academics, Jewish communal leaders, and Israeli politicians decry the rise of a newly transformed type of anti-Semitism as an ideological, social, and political trend, if not a bona fide fact.90 More than 125 years after the public christening of political anti-Semitism and Zionist thought, many observers have returned to a set of assumptions, concepts, and paradigms that were introduced and canonized in debates that shaped turn-of-the-century society and politics across Eastern and Central Europe. However, by embracing many of the same fundamental assumptions, rhetorical tropes, and analytical strategies that characterized and defined early Zionist interpretations of anti-Semitism and Jewish history, much of the contemporary scholarship on anti-Semitism assumes a set of postulates that supply ready-made answers to familiar questions. While Jewish history and the history of Zionism very often unfold along a linear axis from collective catastrophe to communal crisis and from communal crisis to national redemption, the intellectual and research strategies implemented by many critics of the new anti-Semitism have, over the years, become increasingly circular.91 As a result, many of these studies fail to raise and address deeper questions regarding the nature of anti-Jewish animus, its relationship to other forms of prejudice, its strange and recurrent appearance in debates regarding Zionism and the State of Israel, and its ongoing impact on the imagined state and potential fate of “the Jews.”

A second, equally problematic aspect of much of the contemporary scholarship on the new anti-Semitism is the extent to which such approaches have been co-opted and then politicized by a range of political leaders, communal institutions, and assorted Internet warriors, as well as the reciprocal and perhaps inevitable impact of such politically driven debates on many scholars writing on these topics.92 Thus, while many observers will claim that fervent warnings (both academic and political) regarding a resurgence of anti-Semitism today are warranted in the wake of violent and at times deadly attacks against Jewish institutions and individuals in Paris, Brussels, and other locations, others will point to the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Global Forum for Combating Anti-Semitism and similar frameworks as politically motivated endeavors that blur (both purposefully and accidentally) the ostensibly sacrosanct boundaries between the scholarly and the political realms.93

Of course, noting the problematic nature of the intersection and confusion between academic analyses of and political campaigns against anti-Semitism does not mean that anti-Jewish sentiments and actions are not very real problems in a range of societies from Cairo to Charlottesville.94 However, as a result of the ongoing intersection between the two competing, if not at times conflicting, means of understanding anti-Semitism, academic research on the topic over the past few decades has become increasingly conflated with, and in many cases overshadowed by, heated debates regarding the State of Israel, its place in the Middle East, and its relationship to other communities and nations.95 It often seems as though contemporary exchanges regarding the new anti-Semitism are little more than surrogates for ongoing political conflicts, and that the underlying diffusion and confusion between political and scholarly approaches to the study of anti-Semitism leave little room for ostensibly neutral, potentially objective, and fundamentally apolitical interpretations of the phenomenon.96 The recurrent intersection and interference between political efforts to counteract anti-Semitism in the present and the scholarly study of the phenomenon in the past have led some observers to ask: Is the reemergence of the traditional Zionist interpretation of anti-Semitism over the past generation or two a reflection of empirical findings, a by-product of deeply embedded political and ideological predispositions, or an unhealthy mixture of both?97 When do ideological underpinnings, political engagement, and personal investment begin to influence research agendas, muddle intellectual clarity, and transgress the boundary separating (and also protecting) academic freedom from political pressures?

Of course, similar methodological pitfalls and intellectual dilemmas plague a range of academic fields with contemporary implications, especially those bound to and inspired by the politics of identity and the inherently human need for community and belonging. While these and related questions lie beyond the scope of this roundtable, studying anti-Semitism in comparison to or alongside other forms of prejudice and racism may provide the key to overcoming the biggest problem facing the study of anti-Jewish animus today: the constant intersection and seemingly unavoidable interference between political efforts to combat anti-Semitism and academic research on the phenomenon.98 First, the creation of a common scholarly framework for the study of anti-Semitism alongside other forms of prejudice and racism would problematize, if not destabilize, prevailing assumptions regarding the ostensibly unique nature of anti-Semitism. Second, adopting a collective or comparative approach to the study of anti-Jewish animus would help reposition the dialectical relationship between anti-Semitism and various forms of Zionism. Additionally, researching anti-Semitism alongside or in comparison to other types of racism—including Islamophobia—would challenge commonly held assumptions regarding the central role of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict within the framework of the “new anti-Semitism.”99 Lastly, a new set of studies that examine anti-Semitism and other kinds of prejudice and racism within the same academic framework would encourage scholars from a range of fields to read, critique, and interact with one another in a sustained and meaningful fashion.

Ultimately, such a return to the old-new contextual-comparative paradigm for the study of anti-Semitism might prompt some scholars to reconsider how they conceive of and study anti-Jewish prejudice. To paraphrase Joan Wallach Scott’s seminal essay on the study of gender, a methodological and intellectual repositioning and subsequent reevaluation of the field might encourage some scholars to consider the extent to which “anti-Semitism” is indeed a useful category of scholarly analysis.100 As one of the world’s leading scholars of the Holocaust, Yehuda Bauer, has recently confessed, “The term antisemitism is, as many of us realize, the wrong term for what we try to describe and analyze.”101 Inspired by these and other critiques of the state of the field, some scholars might even come to the conclusion that the axiomatic assumption that anti-Semitism is a unique historical phenomenon that is best studied in academic isolation ends up proving, willy-nilly, that anti-Semitism is a distinct form of prejudice that targets a specific people, that one can find evidence of its existence from time immemorial, and that it has recently morphed into a latter-day libel designed to delegitimize, deconstruct, and dissolve “the Jewish State.”

Only time will tell whether scholars who embark upon the path of studying anti-Semitism alongside or in comparison to other forms of hatred and racism will be able to create and implement a new set of key concepts, basic questions, scholarly paradigms, research practices, and narrative strategies that will together liberate the study of anti-Jewish animus from contemporary political concerns, and in doing so, move it to an autonomous, protected academic space. We may discover that these efforts to create new scholarly frameworks and tools for the study and understanding of anti-Jewish prejudices and hostilities will simply produce a new set of methodological, scholarly, and political dilemmas that future generations of scholars will similarly find to be politically motivated, academically suspect, and intellectually unsatisfying. Ultimately, each new research paradigm may seem like nothing more than a newly constructed and much-celebrated bypass that does little more than delay the morning traffic deluge to the following intersection. While many scholars have long since come to terms with these and other limits inherent in academic research and writing, many community members and political actors have much greater difficulty accepting the position that academic scholarship—however well crafted and conducted—remains a fundamentally imperfect, if not deeply flawed, enterprise.102 In light of these and related dilemmas, students and scholars of anti-Jewish prejudice and racism may ultimately find themselves returning full circle to questions regarding the troubling, vexing, and potentially inevitable intersection between academic research and political concerns. Perhaps Leon (Yehuda Leib) Pinsker, Theodor Herzl, Ezra Mendelsohn, and other keen observers of modern Jewish history and society were alarmingly prescient, if not profoundly prophetic, in their ostensibly postmodern observations that anti-Semitism, Zionism, and “the Jews” are—by their very nature—intellectually, culturally, politically, academically, and forever bound to one another as “inseparable companions.”

Scott Ury is Senior Lecturer in Tel Aviv University’s Department of Jewish History, where he is also Director of the Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism. His research focuses on Jewish history in nineteenth- and twentieth-century East-Central Europe, with a particular interest in urban societies, modern politics, and Polish-Jewish relations. His monograph Barricades and Banners: The Revolution of 1905 and the Transformation of Warsaw Jewry (Stanford University Press, 2012) was awarded the Reginald Zelnik Book Prize by the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies. He is also co-editor (with Michael L. Miller) of Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism and the Jews of East Central Europe (Routledge, 2014) and (with Israel Bartal and Antony Polonsky) of Jews and Their Neighbours in Eastern Europe since 1750 (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2012).

I would like to thank Jonathan Judaken and the various readers for and at the AHR, as well as many of the participants in the University of Toronto’s fall 2016 “Key Concepts in the Study of Antisemitism” workshops, those at the “Polish Jewish History Revisited” conference at Bar-Ilan University in November 2017, and those at the summer institute on “Teaching about Antisemitism in the Twenty-First Century” at York University, Toronto, in July 2018 for their constructive comments regarding different versions of this article.

Notes

Ezra Mendelsohn, “Interwar Poland: Good for the Jews or Bad for the Jews?,” in Chimen Abramsky, Maciej Jachimczyk, and Antony Polonsky, eds., The Jews in Poland (Oxford, 1986), 130–139. See also Rafael F. Scharf, “In Anger and in Sorrow: Towards a Polish-Jewish Dialogue,” Polin 1 (1986): 270–277, here 272; Scott Ury, Barricades and Banners: The Revolution of 1905 and the Transformation of Warsaw Jewry (Stanford, Calif., 2012). For an overview of the field of modern Jewish politics, see Ezra Mendelsohn, On Modern Jewish Politics (New York, 1993). For more on Jewish politics in the interwar era, see Mendelsohn, Zionism in Poland: The Formative Years, 1915–1926 (New Haven, Conn., 1981); Mendelsohn, The Jews of East Central Europe between the World Wars (Bloomington, Ind., 1983).

See, for example, the different essays published in Jeffrey Herf, guest ed., Convergence and Divergence: Anti-Semitism and Anti-Zionism in Historical Perspective, Special Issue, Journal of Israeli History 25, no. 1 (2006), especially Derek J. Penslar, “Anti-Semites on Zionism: From Indifference to Obsession,” 13–31, and David N. Myers, “Can There Be a Principled Anti-Zionism? On the Nexus between Anti-Historicism and Anti-Zionism in Modern Jewish Thought,” 33–50.

See, for example, Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York, 1972); Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1971; repr., New York, 1994). See also Hayden White, “Preface,” in White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore, 1973), ix–xii; White, “Introduction: The Poetics of History,” ibid., 1–42; White, “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality,” chap. 1 in White, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore, 1987), 1–25.

For engaging discussions of these two points in different contexts see, respectively, David Engel, “Away from a Definition of Antisemitism: An Essay in the Semantics of Historical Description,” in Jeremy Cohen and Moshe Rosman, eds., Rethinking European Jewish History (Oxford, 2009), 30–53; and, Brian Porter, When Nationalism Began to Hate: Imagining Modern Politics in Nineteenth-Century Poland (New York, 2002).

For a thought-provoking study of Zionism in this period, see Michael F. Stanislawski, Zionism and the Fin de Siècle: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism from Nordau to Jabotinsky (Berkeley, Calif., 2001). See also Carl E. Schorske, “Politics in a New Key: An Austrian Trio,” chap. 3 in Schorske, Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York, 1981), 116–180.

Leo Pinsker, “Auto-Emancipation: An Appeal to His People by a Russian Jew,” trans. D. S. Blondheim, in Pinsker, Road to Freedom: Writings and Addresses, ed. B. [Benzion] Netanyahu (1944; repr., Westport, Conn., 1975), 74–106, here 101.

Key studies of these developments include I. Michael Aronson, Troubled Waters: The Origins of the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia (Pittsburgh, Pa., 1990); and Hans Rogger, “Conclusion and Overview,” in John D. Klier and Shlomo Lambroza, eds., Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History (Cambridge, 1992), 314–372.

For a nuanced analysis of Pinsker’s early years, see Dimitry Shumsky, “Leon Pinsker and ‘Auto-Emancipation!’ A Reevaluation,” Jewish Social Studies 18, no. 1 (2011): 33–62. Examples pointing to 1881 as Pinsker’s moment of truth include David Vital, The Origins of Zionism (Oxford, 1975), 122–132: “In 1881, however, the facts were plainly otherwise and their effect on Pinsker was shattering. He broke with all that he had stood for before—abruptly, finally, and in a manner that was uncharacteristically dramatic” (125). See also Gideon Shimoni, The Zionist Ideology (Hanover, N.H., 1995), 32–33. “It would not be exaggerated to say that Pinsker’s Autoemancipation became for the ideology of Zionism what Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto was for that of socialism.” Olga Litvak offers an enlightening discussion of these and related developments in an as yet unpublished essay, “Judaeophobia and Palestinophilia: Symptoms of Emancipation and Anxiety in Late Imperial Russia.” I am grateful to the author for sharing a preliminary version of it with me.

On these central figures, see the following invaluable studies: Yehudah Mirsky, Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution (New Haven, Conn., 2014); Anita Shapira, Ben-Gurion: Father of Modern Israel, trans. Anthony Berris (New Haven, Conn., 2014); Steven J. Zipperstein, Elusive Prophet: Ahad Ha’am and the Origins of Zionism (London, 1993).

Pinsker, “Auto-Emancipation,” 76, 81, emphasis in the original.

Ibid., 77.

Ibid., 78, and also 83.

Ibid., 78.

Ibid., 80.

Ibid., 91, emphasis in the original. See also 79.

Ibid., 91.

Ibid., 94, emphasis in the original.

Ibid., 79.

On Herzl’s early thoughts regarding “the Jewish Question,” see Jacques Kornberg, Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism (Bloomington, Ind., 1993), 121, 124, 129.

Theodor Herzl to Albert Rothschild, Paris, June 28, 1895, in The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, ed. Raphael Patai, trans. Harry Zohn, 5 vols. (New York, 1960), 1: 190. See also Herzl, The Jewish State: An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question, trans. Sylvie D’Avigdor, 7th ed. (London, 1993), 14–15.

Herzl, The Jewish State, 25.

See Herzl’s characteristically immodest comments in The Complete Diaries, 2: 581, September 3, 1897: “At Basel I founded the Jewish State.”

On the central role of technology in the Zionist project, see Derek J. Penslar, Zionism and Technocracy: The Engineering of Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 1870–1918 (Bloomington, Ind., 1991). For larger discussions regarding technology and its place in modern utopia, see Howard P. Segal, Technological Utopianism in American Culture (Chicago, 1985).

Herzl, The Jewish State, 8.

Theodor Herzl to Moritz Güdemann, Paris [?], June 16, 1895, in The Complete Diaries, 1: 109. On Herzl and Güdemann, see Josef Fraenkel, “Moritz Güdemann and Theodor Herzl,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 11 (1966): 67–82.

“Are the sufferings of the Jews not yet grave enough?” Herzl, The Jewish State, 9. Also note Herzl’s comment in an unsolicited letter to Otto von Bismarck: “I believe I have found the solution to the Jewish Question. Not a solution, but the solution, the only one.” Herzl to Bismarck, Paris [?], June 19, 1895, in The Complete Diaries, 1: 118, emphasis in the original.

Herzl, The Jewish State, 15.

Ibid., 27.

Ibid., 15.

For additional discussions regarding the history of Jewish politics as well as those related to the history and nature of a distinctly Jewish polity, see Daniel J. Elazar and Stuart A. Cohen, The Jewish Polity: Jewish Political Organization from Biblical Times to the Present (Bloomington, Ind., 1985); and Michael Walzer, Menachem Lorberbaum, Noam J. Zohar, and Yair Lorberbaum, eds., The Jewish Political Tradition, vol. 1: Authority (New Haven, Conn., 2000).

Herzl, The Jewish State, 17.

See Robert Liberles, Salo Wittmayer Baron: Architect of Jewish History (New York, 1995), 340, 348, 355.

Ibid., 281, 345. See also David Engel, Historians of the Jews and the Holocaust (Stanford, Calif., 2010), 44–51; Engel, “Crisis and Lachrymosity: On Salo Baron, Neobaronianism, and the Study of Modern European Jewish History,” Jewish History 20, no. 3–4 (2006): 243–264; Ismar Schorsch, “The Lachrymose Conception of Jewish History,” in Schorsch, From Text to Context: The Turn to History in Modern Judaism (Hanover, N.H., 1994), 376–388; Adam Teller, “Revisiting Baron’s ‘Lachrymose Conception’: The Meanings of Violence in Jewish History,” AJS Review 38, no. 2 (2014): 431–439, here 431, 439.

Salo W. Baron, “Newer Emphases in Jewish History,” in Baron, History and Jewish Historians: Essays and Addresses (Philadelphia, 1964), 90–106, here 96. For a compelling discussion of the different definitions and uses of the term “anti-Semitism,” see Engel, “Away from a Definition of Antisemitism.”

Salo W. Baron, “Who Is a Jew?,” in Baron, History and Jewish Historians, 5–22, here 14–15. On this point, see also Alon Confino, A World without Jews: The Nazi Imagination from Persecution to Genocide (New Haven, Conn., 2015), 71.

Salo W. Baron, “Ghetto and Emancipation,” in Leo W. Schwarz, ed., The Menorah Treasury: Harvest of Half a Century (Philadelphia, 1964), 50–63, here 61, 62.

See Baron’s discussion of the topic in Salo W. Baron, “Changing Patterns of Anti-Semitism,” Jewish Social Studies 38, no. 1 (1976): 5–38. Although overwhelmingly loyal to his subject, Baron’s biographer, Robert Liberles, is less than convinced about the efficacy of Baron’s self-declared campaign against Jewish lachrymosity. See, for example, Liberles, Salo Wittmayer Baron, 281, 344–348. For additional comments regarding Baron’s interpretation of the place of anti-Semitism in the course of Jewish history, see Teller, “Revisiting Baron’s ‘Lachrymose Conception,’” 431, 433; Schorsch, “The Lachrymose Conception of Jewish History,” 382–385. For a discussion of Baron’s attitude toward Zionism, see Liberles, Salo Wittmayer Baron, 214–216.

Baron, “Ghetto and Emancipation,” 63. For Baron’s views of Jewish history and community as well as his interpretation of relations between Jews and non-Jews, see Engel, “Crisis and Lachrymosity,” 248, 264; Engel, Historians of the Jews and the Holocaust, 44–46; Elisheva Carlebach, “Between Universal and Particular: Baron’s Jewish Community in Light of Recent Research,” AJS Review 38, no. 2 (2014): 417–421, here 421; Schorsch, “The Lachrymose Conception of Jewish History,” 380–382; Teller, “Revisiting Baron’s ‘Lachrymose Conception,’” 436–437. “Perhaps what resonated most with his [Baron’s] American Jewish devotees was his rejection of the negative Zionist prognosis concerning the possibilities of diasporic Jewish life, a rejection important for legitimizing the American Jewish project. This Americanization of Baron’s message, as it were, was facilitated no doubt by Baron’s own success in integrating himself and his work into the American academy and by his increasingly enthusiastic identification with the American and American Jewish environments beginning in the 1940s.” Engel, “Crisis and Lachrymosity,” 264.

For a discussion of Arendt and Baron, see Engel, Historians of the Jews and the Holocaust, 171–175. See also Gil Rubin, “Salo Baron and Hannah Arendt: An Intellectual Friendship,” Naharaim 9, no. 1–2 (2015): 73–88; Arie Dubnov, “Me-Hilberg al Arendt (vebe-hazara?): Ha’ara’ot al hurban Yehudei Europa ve-ha-banaliut shel ha-ro’a,” Tabur 7 (2016): 54–62. On this generation of scholars, see Steven E. Aschheim, Beyond the Border: The German-Jewish Legacy Abroad (Princeton, N.J., 2007).

Note Baron’s personal yet detached obituary enumerating Arendt’s life and works: Salo W. Baron, “Personal Notes: Hannah Arendt (1906–1975),” Jewish Social Studies 38, no. 2 (1976): 187–189.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951; repr., New York, 1973), 7. See also xii and 5–6. For discussions of these and related points, see Jonathan Judaken, “Blindness and Insight: The Conceptual Jew in Adorno and Arendt’s Post-Holocaust Reflections on the Antisemitic Question,” in Lars Rensmann and Samir Gandesha, eds., Arendt and Adorno: Political and Philosophical Investigations (Stanford, Calif., 2012), 173–196, here 177–178; Richard I. Cohen, “Breaking the Code: Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem and the Public Polemic—Myth, Memory and Historical Imagination,” Michael: On the History of the Jews in the Diaspora 13 (1993): 29–85, here 35–36. For more on Arendt and anti-Semitism, see Julia Schulze Wessel and Lars Rensmann, “The Paralysis of Judgment: Arendt and Adorno on Anti-Semitism and the Modern Condition,” in Rensmann and Gandesha, Arendt and Adorno, 197–225.

Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 7, xi.

Ibid., 9.

Ibid., xv; see also 120.

Ibid., 7. For more on this point, see Judaken, “Blindness and Insight,” 178.

Note Cohen’s astute reading of Arendt in “Breaking the Code,” 34–36. “The real enemy became, in the Herzlian construct, the true ally, and even Nazism could appear positively for it showed the truth of Zionism” (36).

For a contemporary critique of Arendt’s work, see Jacob Robinson, And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight: The Eichmann Trial, the Jewish Catastrophe, and Hannah Arendt’s Narrative (Philadelphia, 1965). Also note Gershom Scholem’s infamous comment in a personal letter to Arendt that she lacked a “[l]ove of the Jewish people” (ahavat yisrael). Gershom Scholem to Hannah Arendt, Jerusalem, June 23, 1963, as well as Arendt’s response, Arendt to Scholem, New York, July 24, 1963, in Arendt, The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age, ed. Ron H. Feldman (New York, 1978), 241–242 and 246–247, respectively. For a learned overview of the different debates regarding Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, see Richard I. Cohen, “A Generation’s Response to Eichmann in Jerusalem,” in Steven E. Aschheim, ed., Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem (Berkeley, Calif., 2001), 253–277. See also Aschheim’s spirited rehabilitation of Arendt on these and related points in “Introduction: Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem,” ibid., 1–15.

Jacobs discusses at length the cooperation between the American Jewish Committee and members of the Frankfurt School in the publication of the postwar series Studies in Prejudice. See Jack Jacobs, The Frankfurt School, Jewish Lives, and Antisemitism (New York, 2015), 82–102. Judaken analyzes many of the same works, in particular T. W. Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and R. Nevitt Sanford, eds., The Authoritarian Personality (New York, 1950); and Leo Lowenthal and Norbert Guterman, Prophets of Deceit: A Study of the Techniques of the American Agitator (New York, 1949), in “Blindness and Insight,” 189–192.

“These considerations, which suggest the advantage of making anti-Semitism a point of departure for research, were also some of the hypotheses that guided the research as a whole. The study of anti-Semitism may well be, then, the first step in a search for antidemocratic trends in ideology, in personality, and in social movements.” Daniel J. Levinson, “The Study of Anti-Semitic Ideology,” in Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford, The Authoritarian Personality, 57–101, here 57–58.

See, for example, Schulze Wessel and Rensmann, “The Paralysis of Judgment,” 197–198.

Max Horkheimer and Samuel H. Flowerman, “Foreword to Studies in Prejudice,” in Lowenthal and Guterman, Prophets of Deceit, v–viii, here v.

An important exception to this trend is David Nirenberg’s recent Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York, 2013). Despite the author’s repeated attempts to counter current trends in the study of anti-Semitism, many of the book’s finer points seem to have fallen on deaf ears. See especially 7, 11, 85, 91, 461, 463.

For more on Ettinger’s life and work, see the recent Hebrew biography by Jacob Barnai, Shmuel Ettinger: Historion, moreh ve-ish tsibor (Jerusalem, 2011). On Ettinger’s status and influence in the academic and public realms, see Daniel Gutwein, “Shmuel Ettinger, ha-antishemiyut ve-‘ha-tezah she-me‘ever le-tsiyonut’: Historiografiya, politika ve-ma‘amad,” Iyunim be-tekumat yisrael 23 (2013): 83–175, here 84–85, 165–169.

See Shmuel Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah: Pirkei mihkar ve-‘iyun (Tel Aviv, 1979). For discussions regarding “the abandonment of the Jews” in different contexts, see David S. Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941–1945 (New York, 1984); Ruth R. Wisse, If I Am Not for Myself: The Liberal Betrayal of the Jews (New York, 1992).

On Ettinger’s influence in Israeli academia, see Barnai, Shmuel Ettinger, 323. See also ibid., 105; Gutwein, “Shmuel Ettinger,” 84, 151; Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah, v. For a critique of Ettinger’s work by another notable Israeli scholar, see Shulamit Volkov, “Tenu‘ah be-ma‘agal: Heker ha-antishemiyut me-Shmuel Ettinger ve-hazara,” Zion 76, no. 3 (2011): 369–379.

Shmuel Ettinger, “Sinat-yisrael be-retzifut historit,” in Shmuel Almog, ed., Sinat Yisrael le-doroteha (Jerusalem, 1980), 11–23, here 11, and also 13–17. For similar critiques by Ettinger of Arendt and other thinkers, see Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah, 210; Ettinger, “Conclusion,” in Jacob M. Kelman and S. Ettinger, eds., Anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union: Its Roots and Consequences, 3 vols. (Jerusalem, 1979), 1: 202–207: “The late Hannah Arendt, for instance, Bruno Bettelheim and others consider there is no connection between contemporary anti-Semitism and historic Judaeophobia of ancient times or of the Middle Ages. I think the connection exists” (202). For more on these and related critiques of Arendt, see Cohen, “A Generation’s Response to Eichmann in Jerusalem,” and Cohen, “Breaking the Code.”

Ettinger, “Sinat-yisrael be-retzifut historit,” 17. On the “Jerusalem school of Jewish history,” see David N. Myers, Re-Inventing the Jewish Past: European Jewish Intellectuals and the Zionist Return to History (New York, 1995). On Ettinger’s role in the development of “the Jerusalem school,” including his close relationship with other key figures at the time, such as Ben-Zion Dinur and Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson, see Olga Litvak, “The God of History,” in Uzi Rebhun, ed., The Social Scientific Study of Jewry: Sources, Approaches, Debates (New York, 2014), 290–302, here 295–296.

Ettinger, “Sinat-yisrael be-retzifut historit,” 17.

Ettinger, “Ha-antishemiyut ha-modernit veha-Shoah,” in Shmuel Almog and Otto Dov Kulka, eds., Historiyah ve-historionim (Jerusalem, 1992), 258–266, here 258. For additional comments regarding the historical roots and longevity of anti-Semitism, see Ettinger, “Sinat-yisrael be-retzifut historit,” 20, 22; Ettinger, “Le’umiyut ve-antishemiyut,” in Almog and Kulka, Historiyah ve-historionim, 225–236, here 225.

Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah, 210–211, 225. See also, for example, Barnai, Shmuel Ettinger, 336, 373–374; Gutwein, Shmuel Ettinger, 89–100, 143–145, 165–169; Volkov, “Tenu‘ah be-ma‘agal,” 371–372. For a discussion regarding the central place of anti-Semitism in the work of Jacob Katz, one of the most important Israeli scholars of Jewish history, see Richard I. Cohen, “How Central Was Anti-Semitism to the Historical Writing of Jacob Katz?,” in Jay M. Harris, ed., The Pride of Jacob: Essays on Jacob Katz and His Work (Cambridge, Mass., 2002), 125–140: “The interplay between the two vantage points—anti-Jewish attitudes and Jewish separateness—was constant and had a seminal role on the development of Jewish history. Thus Katz strongly rejected the notion that anti-Judaism or anti-Semitism had no place in Jewish history” (130).

Ettinger, “Sinat-yisrael be-retzifut historit,” 17.

Barnai’s biography dedicates an entire subchapter to Ettinger’s commitment to and involvement with Soviet Jewry; Shmuel Ettinger, 272–285. “From the 1960’s on, Ettinger became increasingly absorbed with his activities regarding Soviet Jewry; and his cooperation with ‘Nativ’ found its expression in his teaching, his publications such as those on antisemitism in the Soviet Union, advising students working on projects on the topic and intensive reading” (276).

Ettinger, “Conclusion,” 202–204, here 203. See also Ettinger, “Introduction,” in Anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union, 3: i–xiv, here v–viii; Ettinger, “Historical Roots of Anti-Semitism in the USSR,” ibid., 1: 11–24, here 11–15, 19.

Shmuel Ettinger, “Soviet Antisemitism after the Six-Day War,” in Yehuda Bauer, ed., Present-Day Antisemitism: Proceedings of the Eighth International Seminar of the Study Circle on World Jewry under the Auspices of the President of Israel, Chaim Herzog, Jerusalem, 29–31 December 1985 (Jerusalem, 1988), 49–56, here 52.

Ettinger, “Introduction,” vi. See also Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah, 216–217; and Ettinger, “Historical Roots of Anti-Semitism in the USSR,” 14, 18–19: “From both the right and the left there emerges the stereotype of the Jew as exploiter, plunderer, a parasite always living at the expense of others” (14). A nuanced historical thinker who was also deeply invested in modern, secular ideologies, Ettinger was not one to overlook periods of relative openness in Russian history. See, for example, “Historical Roots of Anti-Semitism in the USSR,” 13, 17–18; “Introduction,” v–vi; “Leumiyut ve-antishemiyut,” 231.

“Those who worked with him in this period described his involvement as his act of ‘Great Correction’ . . . or, as ‘penance’ for his communist period.” Barnai, Shmuel Ettinger, 273. For more on the impact of Ettinger’s personal transformations on his academic scholarship, see Litvak’s illuminating comments in “The God of History,” 295–297.

On Ettinger’s communist period, see Barnai, Shmuel Ettinger, chap. 3 and 42–43. “The young Ettinger was soon caught up in the faith of communism from the beginning of his university studies. Quickly, he and several of his friends constructed a unique form of communism in the land of Israel, one that attempted to synthesize communism and Jewish nationalism” (46).

Ettinger, “Introduction,” vii. See also Ettinger, “Soviet Antisemitism after the Six-Day War,” 50. Also note Ettinger’s comments regarding the duplicity of the Russian intelligentsia in “Introduction,” xiii.

Ettinger, “Introduction,” xiv. For similar warnings regarding the deep roots and potentially fatal implications of Soviet anti-Semitism, see Ettinger, “Soviet Antisemitism after the Six-Day War,” 50, 56.

See also Gutwein, “Shmuel Ettinger,” 149–150.

See Ettinger, “Soviet Antisemitism after the Six-Day War,” 49, also 50. See also Ettinger, “Introduction,” i–iii. On the connection between the anti-Cosmopolitan campaign and Soviet anti-Semitism, see Ettinger, “Historical Roots of Anti-Semitism in the USSR,” 21–24. Ettinger believed that Soviet anti-Zionism could be traced back to the Russian intelligentsia’s unwillingness “to recognize the Jews’ right to national self-determination or their right to regard themselves as an ethnic or national group”; “Historical Roots of Anti-Semitism in the USSR,” 18. See also Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah, 235–236.

“The great hopes raised by European liberalism of the nineteenth century regarding the development of industry and the economy, the most extreme representatives of which assumed that the individual’s efforts to cultivate his personal capabilities and increase his own revenues would usher in the development of an ideal society—have evaporated.” Shmuel Ettinger, “Ha-antishemiyut ve-anti-Zionut be-dor ha-tzair be-olam ha-ma‘aravi,” in Antishemiyut ha-yom (Jerusalem, 1985), 3–9, here 3. See also Gutwein, “Shmuel Ettinger,” 150–151. Many of Ettinger’s points are echoed in a series of pamphlets that were published in the same year by prominent Israeli scholars as part of the prestigious Study Circle on World Jewry in the Home of the President of Israel. See, for example, Yehuda Bauer, Antisemitism Today: Myth and Reality (Jerusalem, 1985); Emmanuel Sivan, Islamic Fundamentalism and Antisemitism (Jerusalem, 1985); and, Robert Wistrich, Anti-Zionism as an Expression of Antisemitism in Recent Years (Jerusalem, 1985).

Ettinger, “Ha-antishemiyut ve-anti-Zionut be-dor ha-tzair be-olam ha-ma‘aravi,” 7. See also Ettinger, Ha-antishemiyut be-‘et ha-hadashah, 221, 231.

Note Litvak’s astute observation that Ettinger was “virtually hand-picked to succeed [Ben-Zion] Dinur (after the latter was appointed minister of education) as the historian of modern Jewry for the fledgling Jewish state”; “The God of History,” 295.

For a summary of Wistrich’s oeuvre that highlights his relevance to both the public and the academic realms, see Michael Berkowitz, “Robert S. Wistrich and European Jewish History: Straddling the Public and Scholarly Spheres,” Journal of Modern History 70, no. 1 (1998): 119–136. According to Barnai, Ettinger was responsible for bringing Wistrich to the Hebrew University from London in 1982; Shmuel Ettinger, 146.

Recent works that adopt (or at the very least reflect) many of Wistrich’s main points include Paul Iganski and Barry Kosmin, eds., A New Antisemitism? Debating Judeophobia in 21st-Century Britain (London, 2003); Anthony Julius, Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England (Oxford, 2010), especially xxiv, 8, 97, 357, 359, 441, 483, 538, 583; Kenneth L. Marcus, The Definition of Anti-Semitism (New York, 2015); Dina Porat, “The International Working Definition of Antisemitism and Its Detractors,” Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 5, no. 3 (2011): 93–101, here 93–94, 99–100; Alvin H. Rosenfeld, Deciphering the New Antisemitism (Bloomington, Ind., 2015); Rosenfeld, “Introduction,” in Rosenfeld, ed., Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives (Bloomington, Ind., 2013), 1–7, especially 6; Rosenfeld, “The End of the Holocaust and the Beginnings of a New Antisemitism,” ibid., 521–533, here 525, 528, 529; Pierre-André Taguieff, Une France antijuive? Regards sur la nouvelle configuration judéophobe: Antisionisme, propalestinisme, Islamisme (Paris, 2015); Taguieff, La nouvelle judéophobie (Paris, 2002); and, Michel Wieviorka, The Lure of Anti-Semitism: Hatred of Jews in Present-Day France, trans. Kristin Couper Lobel and Anna Declerck (Leiden, 2007).

See Robert S. Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession: Anti-Semitism from Antiquity to the Global Jihad (New York, 2010), 3, 9, 13, 17–21, 62, 76, 104–106; and, Wistrich, Antisemitism: The Longest Hatred (London, 1992).

Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession, 79. For a similar perspective in current literature, see Rosenfeld, “Introduction,” 1, 6–7. Also note the statement of the newly launched journal Antisemitism Studies, http://antisemitismstudies.com/index.html, which speaks of “the millennial phenomenon of antisemitism.”

Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession, 13, emphasis in the original.

See Wistrich’s earlier call for the contextualization of anti-Semitism as well as the careful use of the term; Antisemitism, xvi–xvii, xxvi.

Robert S. Wistrich, From Ambivalence to Betrayal: The Left, the Jews, and Israel (Lincoln, Nebr., 2012), xi, xiii, 3, 14, 15–16, 18, 25. See also Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession, 44–45, 53, 56, 63, 68, 71–77. For additional works that echo this position, see Alvin H. Rosenfeld’s spirited essay “Progressive” Jewish Thought and the New Antisemitism (New York, 2006). See also Rosenfeld, “Introduction,” 6; Wisse, If I Am Not for Myself. Also note Porat’s sarcastic comment regarding debates within the UK’s University and College Union (UCU): “Ostensibly, the UCU stands for equality, liberalism and the inclusion of all narratives of all individuals and groups. However, when it concerns Jews and Israelis those values are abandoned”; “The International Working Definition of Antisemitism,” 100.

Wistrich, From Ambivalence to Betrayal, 3, emphasis in the original. “For such radical Leftists, double standards, moral blindness, and self-righteous narcissism appear to have become a way of life” (15–16).

On Herzl’s increasing exasperation with European society and his repeated confrontation with turn-of-the-century anti-Semitism, see Kornberg’s nuanced biography Theodor Herzl, especially 102–103, 111, 129, 149, 185.

Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession, 5–6, 15, 34–35, 48, 62; Wistrich, From Ambivalence to Betrayal, xi, xv, 1, 17. See also Rosenfeld, “The End of the Holocaust and the Beginnings of a New Antisemitism,” 521–522, 525, 529; Yehuda Bauer, “Preface,” in Bauer, Present-Day Antisemitism, 5–8. For studies that question or challenge this approach, see Jonathan Judaken, “So What’s New? Rethinking the ‘New Antisemitism’ in a Global Age,” Patterns of Prejudice 42, no. 4–5 (2008): 531–560; Brian Klug, “Interrogating ‘New Anti-Semitism,’” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36, no. 3 (2013): 468–482; Moshe Zuckermann, ed., Antisemitismus, Antizionismus, Israelkritik (Göttingen, 2005).

Wistrich, From Ambivalence to Betrayal, 1. Rosenfeld writes: “Typically expressing itself in objections to Jewish particularism and, especially, in efforts to demonize and delegitimize Jewish national existence in the State of Israel, this new version of Judeophobia is at the core of much of today’s anti-Jewish hostility”; “Introduction,” 3. See also Porat, “The International Working Definition of Antisemitism”; Iganski and Kosmin, A New Antisemitism?

Note Judith Butler’s comment: “To say that all Jews hold a given view on Israel or are adequately represented by Israel or, conversely, that the acts of Israel, the state, adequately stand for the acts of all Jews, is to conflate Jews with Israel and, thereby, to commit an anti-semitic reduction of Jewishness.” Butler, “No, It’s Not Anti-Semitic: The Right to Criticise Israel,” London Review of Books 25, no. 16 (2003): 19–21, https://www.lrb.co.uk/v25/n16/judith-butler/no-its-not-anti-semitic. On various examples of ideological transposition between anti-Semitism and its Jewish opponents, see Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 7, 120. See also Cohen’s comments on Arendt in “Breaking the Code,” 36.

Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession, 62. See also Robert Wistrich, “Anti-Zionism and Anti-Semitism,” Jewish Political Studies Review 16, no. 3–4 (2004): 27–31, http://www.jcpa.org/phas/phas-wistrich-f04.htm. I would like to thank James Loeffler for sharing with me this and other sources.

For a discussion of this dynamic in a different context, see Israel Bartal and Scott Ury, “Between Jews and Their Neighbours: Isolation, Confrontation and Influence in Eastern Europe,” Polin 24 (2012): 3–30.

For a learned analysis of these debates, see Daniel J. Schroeter’s essay “‘Islamic Anti-Semitism’ in Historical Discourse” in this roundtable.