Edu Nandlal couldn’t sleep. Many of the other passengers on Surinam Airways flight 764 from Amsterdam Schiphol to Paramaribo Zanderij had decided to get some rest on the 12-hour journey. But this was the first time Nandlal had returned to Suriname since leaving for the Netherlands after the military coup in 1980. He wanted to see home as the plane approached.

Most were still sleeping when the flight began its descent, in the early hours of Wednesday 7 June 1989. Nandlal looked out of the window and saw lights from houses in the jungle shining. Then he felt something hit the plane. And then something else. “Shit,” he thought, “I’m dead.”

‘Everything was good when we left’

The Colourful XI was the initiative of Sonny Hasnoe, a Dutch-Surinamese social worker based in Amsterdam. Hasnoe frequently worked in the most deprived areas of the city, where many fellow immigrants lived. Hasnoe noticed children in these areas tended to benefit hugely from football: their behaviour was generally better and they were more likely to engage and connect with wider Dutch society.

Thus he decided to try raising money and awareness of their plight and the profile of Dutch-Surinamese footballers by bringing together a team of such men who would play some exhibition games. The first was in 1986: a few were played in the Netherlands, in Enschede and Hengelo, without huge national fanfare but that was only half the point. The games had a festival atmosphere, with food and Surinamese music. Players such as Regi Blinker and Ken Monkou made appearances for what became known as the ‘Kleurrijk Elftal’ – the Colourful XI.

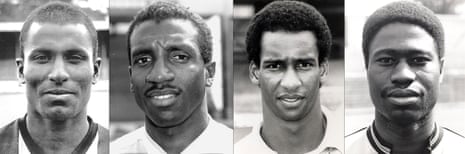

In 1989, plans were made to take the games home. The team would take part in a mini-tournament with three other teams in Paramaribo, Suriname’s capital, and the hope was that some of Dutch football’s biggest names would take part. The previous year’s European Championship-winning squad featured a number of players from a Surinamese background: Aron Winter, Gerald Vanenburg, Frank Rijkaard and of course Ruud Gullit. If some of those Dutch heroes would make the trip, the team’s profile would grow enormously.

But, perhaps predictably, their employers weren’t so keen. Gullit and Rijkaard played for Milan, who weren’t happy for their stars to make an ‘unnecessary’ transatlantic journey at the end of a long season. Similarly Henk Fraser, who had made his international debut earlier that year, joined Winter, Bryan Roy, forward Henny Meijer and goalkeeper Stanley Menzo in being denied permission to travel by Ajax. Menzo and Meijer ignored these instructions and flew out to Suriname separately on 5 June, ostensibly going ‘on holiday’ but with the intention of playing anyway. On 6 June, the rest of the squad gathered at Schipol airport.

The atmosphere among the 17 players, plus coach Nick Stienstra, was celebratory. The stars might not have been there, but plenty of talent was: FC Twente defender Andy Scharmin decided to go rather than play in the Toulon tournament, at least in part so he could take his mother and aunt on the trip home; Steve van Dorpel was about to sign for Roda JC after tearing Ajax apart earlier that season; Andro Knel was a rising star and colourful character who would regularly rollerskate to training.

Nandlal, by his own admission, wasn’t the most talented player in the world, more a workhorse, a midfield grafter who forged a decent career in the Netherlands since arriving in 1980, aged 18. He played for Utrecht under Dick Advocaat but was told he wasn’t tough enough. After moving to Emmen, he was then sold to Vitesse Arnhem, with whom he won promotion to the Eredivisie. “This was the first time I’d been back to Suriname since leaving,” he says now, speaking to an English publication for the first time since 1989. “All my friends were saying they were going to sleep, but I wanted to stay awake to see the landing.”

The flight was delayed by 12 hours because the plane, a 20-year-old DC8 called the ‘Anthony Nesty’, named after the Surinamese swimmer who won gold at the 1988 Olympics, was late arriving from Miami. Still, the mood was cheerful. “Everything was good when we left,” says Nandlal. “There was a band, the Draver Boys, who played music on the plane. The whole flight over the sea was perfect.” The footballers played cards, the Draver Boys sang, and anyone who could sleep through all that got some rest. As they approached Zanderij airport, about 45km south of Paramaribo, Nandlal looked out. “I could see the lights of the small houses in the jungle,” he says. “It was dark, so that’s all I could see.”

About 20 minutes before landing, the cockpit received a weather report which told them visibility was at around 900m because of fog: this, apparently, took them by surprise as visibility was previously judged at about 6km. Captain Will Rogers decided to deploy the instrument landing system (ILS), designed to help planes land in poor weather, despite not being cleared to do so by the control tower at the airport, who told them to follow the standard beacon to the runway. “Legally, we don’t have ILS,” said co-pilot Glyn Tobias. “We have to use it,” said Rogers. The version installed at Zanderij hadn’t been properly developed and wasn’t supposed to be in use yet.

Two attempts at connecting with the ILS were unsuccessful. “I don’t trust that ILS,” said Tobias, as they tried for a third time, eventually managing to connect. But the information provided by the ILS wasn’t reliable, giving an incorrect approach angle. Yet Tobias said he could see the runway, and what he could see more or less aligned with the ILS information.

As they descended, they passed through some low cloud. “Tell ‘em to put the runway lights bright,” said Rogers, twice. An altitude warning alarm sounded, but it was ignored, the crew deciding to trust the ILS. They descended to 300 feet, 200 feet, 150 feet. It was only then they realised they were coming in too low. “Pull up!” said the flight engineer, Warren Rose. On the cockpit recorder, the sound of the first impact was audible. “Pull up!” said Rose again. Then: “That’s it. I’m dead.”

The plane was coming in so low that one of the wings hit the top of a tree, not visible from the plane because of the fog and cloud. “We were going down, then I felt something hitting the airplane,” says Nandlal. “I thought: ‘Shit. Something’s happening.’ Everyone started waking up.” Then the other wing hit a another tree, and the plane flipped over and crashed into the ground, upside down. Most of the 187 on board (178 passengers, nine crew) were killed on impact. Ortwin Linger, a defender for FC Haarlem, survived for three days but died later in hospital. In total, only 11 survived (almost all because they were thrown from the wreckage), plus one dog. Inevitably, the dog was subsequently named ‘Lucky’. Fifteen of the 18 Colourful XI party died.

Nandlal survived thanks to a mid-flight act of courtesy to a man who wasn’t even supposed to be on the flight. Jerry Haatrecht was a midfielder who started his career in Ajax’s youth ranks, but had slipped down a few levels and had been playing amateur football. His brother Winnie, a professional who played for Heerenveen, was invited but could not travel because of his club’s involvement in promotion play-offs, so suggested Jerry. During the flight Haatrecht, a rangy midfielder, was one of those who wanted to get some sleep: Nandlal, a shorter man, offered up his seat which was near the emergency exit, so had more legroom, and they swapped.

“I felt pain in my head, pain in my ear,” says Nandlal. “It was totally dark. It was a complete blackout. They found me at 5am. My seat was in the middle of the airplane. I didn’t have my seatbelt on, and when they found me I was near the cockpit.” He was discovered by the emergency services about an hour and a half after the crash.

Remarkably, the man who heard his cries for help recognised him. “He said: ‘Hey, Edu – I know you. You were in my class at school.” But even with the debris around him, Nandlal didn’t comprehend what was happening. “He said the plane has crashed, and I said: ‘No, why are you telling me that? We’re here to play football.’ You can tell I was in deep shock. I could smell gasoline. I heard people screaming ‘I’m dying, help me!’ I could hear children screaming. But still all I could think was: ‘This is not true, it’s a dream, we’re landing. We’re going to play football.’”

Nandlal had broken his back. He spent five days in hospital in Paramaribo, before being flown back to Holland. He spent 14 months in rehab, some of which spent in a wheelchair, and was told he would never walk again. “I prayed to God. I said to him: ‘Can you let me walk a little? Only a little. Then I’ll feel better. I don’t have to play football, but let me walk a little.’” In the end it was probably more medical expertise than divine intervention, but he eventually did recover. These days he has a limp, but is broadly fine.

The two other survivors from the team were Sigi Lens and Radjin de Haan. Lens, a tall attacker who played for Fortuna Sittard and is the uncle of Sunderland winger Jeremain, never played again but went on to become an agent. “I often wonder: what would become of those players?” he said in a 2014 interview to mark the 25th anniversary of the disaster. “Andy Scharmin was a great talent. He could have gone to the tournament in Toulon with Jong Orange, but chose Suriname because his mother had not been there for a long time. Florian Vijent. Lloyd Doesburg. Jerry Haatrecht. Fred Patrick. Fred was like a little brother to me.”

De Haan was the only one who played after the crash. Seven months later he returned to football, but didn’t last long. He became a coach, working at home and abroad, including a stint in Libya. “I never do much on 7 June,” he said in a rare interview last year. “I was 19 and had a lot of luck. I broke my third vertebrae, tore my shoulder blade and had a lot of bruises. But because I was so young, I was able to work on my recovery very quickly.”

The 15 who died were Scharmin, Van Dorpel, Knel, Haatrecht, Stienstra, Fraser, Linger, Heracles defender Ruud Degenaar, Lloyd Doesburg (an Ajax goalkeeper), Frits Goodings (a team-mate of Nandlal’s at Utretcht), Virgall Joemankha (the only member of the team to play outside Holland, for Cercle Brugge), Willem II full-back Ruben Kogeldans, Fred Patrick of PEC Zwolle, De Graafschap winger Elfried Veldman and Telstar’s Florian Vijent.

Just as some Chapecoense players did before their crash in 2016, in the days before the flight several of those involved felt uneasy. “Nick Stienstra’s wife told me she woke up one night, and he was lying on his back like he was in a coffin,” says Iwan Tol, who wrote Destination Zanderij, a book about the team and the crash. “Andro Knel said a few days before to his mother: ‘This is strange to say, but just know that I love you.’”

In reality the cause was more prosaic. “Everything that could go wrong, did go wrong,” says Tol. “Sigi Lens said that when he stepped on to the plane, he could see it was very old. Some things were just held together with tape.” Rogers, the pilot, was a 66-year-old American who should not have been able to captain the flight: Surinamese regulations disqualified anyone over 60 from taking charge of a commercial airline.

Additionally, Rogers had recently been suspended from flying after landing on the wrong runway, and his co-pilot Tobias had false identity papers. The crew were hired via a separate company by the airline, SLM, but the relevant checks were not properly carried out. They ignored alarms from the ground proximity warning system that told them the plane was coming in too low, turning off the alarm after a few seconds. Assorted protocols, including use of the ILS, were not observed.

The commission which investigated the crash concluded that “as a result of the captain’s glaring carelessness and recklessness the aircraft was flown below the published minimum altitudes during the approach”, while also placing blame on the airline who failed “to observe the pertinent regulations as well as the procedures … concerning qualification and certification during recruitment and employment of the crew members.”

‘It’s always about the footballers but lots of people died’

Of course, this isn’t purely a football tragedy. Maurice Lede is a Dutch TV presenter and Andy Scharmin’s cousin. In 2014, to mark the 25th anniversary of the disaster, Lede went to Suriname to make a documentary about the crash, and he found a country that has not, and almost certainly will not, forget.

“Everybody in one way was involved,” says Lede. “Everybody lost a family member, or someone [close]. It was intense. A lot of people weren’t willing to talk about it because it was really emotional. A lot of people were crying, just when I talked about it. The impact was huge. For a lot of people it felt like yesterday. It’s quite a difference to here in Holland. Here it became known because of the football players, but over there it’s known as the disaster of the country.”

And because it’s primarily known because of the footballers who lost their lives, the other victims are often forgotten. Most were Surinamese people living in the Netherlands, but three top-ranking military officers – Suriname army Chief of Staff, Major Raymond Lieuw Yen Tai, air force commander Major Eddy Djoe and army Chief of Operations, Captain Armand Salomons – were on board too.

“So many more people were on the plane,” says Lede. “Young children who were travelling to see their grandparents. A couple who were on their honeymoon. If the football players weren’t on the flight, it wouldn’t have got as much attention. People say: ‘It’s always about the football players but a lot of people were killed.’”

The crash site is now a curious combination of national mourning hub and grave. Two monuments have been erected, but much of the debris was simply buried in the ground where it fell. “They dug a hole and put parts of the plane in it,” says Lede, “but because many years have passed everything pops up. It was quite intense – painful and weird.”

While the crash is a national tragedy in Suriname, and a fairly well-known story in the Netherlands, it’s not thought of in the same way as the Munich air disaster, or Superga, or Chapecoense, or the Zambia team wiped out in 1993. This is partly because none of the players who died were household names: unlike those four examples, this was not a young, talented team on the verge of greatness. But it’s also probably because many of the victims were immigrants, two cultures bridging thousands of miles.

“In Holland, they say it was a disaster that happened far away,” says Tol. “It’s somewhere between the two lands, and nobody takes responsibility for it. We don’t have a culture of thinking of our heroes like they do in England. The only thing we knew was a few pictures on television of the airplane. It’s well known by football fans, but it’s not like the Busby Babes.”

‘The biggest problems are in your mind’

After his physical recovery, Nandlal tried to start a normal life. “After the crash I don’t worry about football,” he says. “The biggest problems are in your mind. You need five years, 10 years to feel calm. To come to terms with it.”

Survivor’s guilt was inevitable, having escaped the crash that killed so many compatriots. “At the beginning, I always thought about my friends, the ones who died. I felt guilty.” He’s still friends with Sigi Lens, but also Winnie Haatrecht, whose brother died after swapping seats, and their sister.

He scouted a little for FC Utrecht, but in 2002 he started a cleaning company which he still runs, employing people who might otherwise find getting a job more difficult: immigrants, those with criminal records, people with learning difficulties. The guilt lingered, but a decade after the crash it disappeared.

He had a son, Riva, but when he was five-years-old, he was diagnosed with a rare brain tumour. Nandlal received the news, with the implausible cruelty that only a random universe can bring, on 7 June. Riva died in April 2002. “I always said to myself that if you survive an airplane crash, you know what lucky is,” says Nandlal. “But then when my son died, I know what the opposite is. I know both. I know what lucky is, but I also know what shit is. I know the pain. From that day, I felt better [about the crash]. After my son died, I no longer felt guilty.”

Talking to Nandlal, a man who has endured physical and emotional trauma that nobody should have to, it’s notable that he speaks about his life with no anger: at the pilot, the airline, the universe, as he justifiably could. “I don’t feel angry. The pilot made a big mistake,” he says, matter of factly. “I know what life is.”

“Every 7 June, I always think about the people who died. Not just the football players. All the people who died.” Last year Nandlal went back to lay flowers at the scene of the crash. “It made me feel better because I could see they still think about the families over there,” he says. “They don’t forget.”