Abstract

Objectives

To compare the chest computed tomography (CT) findings of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) to other non-COVID viral pneumonia.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases were searched through April 04, 2020, for published English language studies. Studies were eligible if they included immunocompetent patients with up to 14 days of viral pneumonia. Subjects had a respiratory tract sample test positive for COVID-19, adenovirus, influenza A, rhinovirus, parainfluenza, or respiratory syncytial virus. We only included observational studies and case series with more than ten patients. The pooled prevalence of each chest CT pattern or finding was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

From 2263 studies identified, 33 were eligible for inclusion, with a total of 1911 patients (COVID-19, n = 934; non-COVID, n = 977). Frequent CT features for both COVID-19 and non-COVID viral pneumonia were a mixed pattern of ground-glass opacity (GGO) and consolidation (COVID-19, 0.37; 0.17–0.56; non-COVID, 0.46; 0.35–0.58) or predominantly GGO pattern (COVID-19, 0.42; 0.28–0.55; non-COVID 0.25; 0.17–0.32), bilateral distribution (COVID-19, 0.81; 0.77–0.85; non-COVID, 0.69; 0.54–0.84), and involvement of lower lobes (COVID-19, 0.88; 0.80–0.95; non-COVID, 0.61; 0.50–0.82). COVID-19 pneumonia presented a higher prevalence of peripheral distribution (COVID-19 0.77; 0.67–0.87; non-COVID 0.34; 0.18–0.49), and involvement of upper (COVID-19, 0.77; 0.65–0.88; non-COVID 0.18; 0.10–0.27) and middle lobes (COVID-19, 0.61; 0.47–0.76; non-COVID 0.24; 0.11–0.38).

Conclusion

Except for a higher prevalence of peripheral distribution, involvement of upper and middle lobes, COVID-19, and non-COVID viral pneumonia had overlapping chest CT findings.

Key Points

• Most common CT findings of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) were a predominant pattern of ground-glass opacity (GGO), followed by a mixed pattern of GGO and consolidation, bilateral disease, peripheral distribution, and lower lobe involvement.

• Most frequent CT findings of non-COVID viral pneumonia were a predominantly mixed pattern of GGO and consolidation, followed by a predominant pattern of GGO, bilateral disease, random or diffuse distribution, and lower lobe involvement.

• COVID-19 pneumonia presented a higher prevalence of peripheral distribution, and involvement of upper and middle lobes compared with non-COVID viral pneumonia

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of the novel coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) has caused an international outbreak of respiratory illness that ranges from mild, self-limited disease to severe pneumonia and death [1, 2]. The rapid spread of the virus outside China despite local and global attempts to restrain dissemination has garnered international attention, and the WHO declared this outbreak a global pandemic in early March 2020 [3]. Thus far, over one million cumulative cases have been reported worldwide, with a mortality rate of around five percent of cases [3].

Most patients present with fever, dry cough, and dyspnea in reported cohorts [4, 5]. Nearly 90% of hospitalized patients have abnormal findings on chest CT [5, 6], with bilateral ground-glass opacities (GGO) as one of the most common results reported on CT scans of patients with COVID-2019 [5, 6]. Other manifestations, such as consolidations, lower lobe predilection, and predominantly peripheral distribution of disease, are often reported in CT studies of patients with COVID-2019 [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In light of these common imaging manifestations, some authors have suggested considering chest CT as a primary tool for detection of COVID-2019 in epidemic areas as many patients have negative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for coronavirus on the initial presentation [6]. Nonetheless, these imaging findings are not specific to COVID-2019 and could be also be found in other viral pneumonia (e.g., influenza, adenovirus) and non-infectious diseases [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Furthermore, 6 to 25% of healthy asymptomatic patients can present GGO on chest CT scans, finding which has been described as one of the hallmarks of COVID-2019 [40, 41].

The aim of this manuscript was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the chest CT findings of COVID-2019 and other viral pneumonia in immunocompetent adults to evaluate if any discriminatory imaging features may help to distinguish COVID-19 from other respiratory viruses.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was reported following Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) Reporting Guidelines, including the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) and Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines. We searched all available literature published in the PubMed-MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases through April 04, 2020. The databases were comprehensibly searched using the terms “pneumonia,” “viral,” and “imaging” OR “computed tomography.” Equivalent terms for each database and detailed search strategy are included in Supplementary File 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if the following criteria were present: (1) subjects had a positive RT-PCR assay in a respiratory tract sample for one of the following viruses: 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), adenovirus (AdV), influenza A H1N1; rhinovirus (RNV); parainfluenza virus (PIV); respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); (2) report of chest computed tomography (CT) findings of viral pneumonia, including at least one of the following imaging features: predominant CT pattern or CT findings; (3) cases of acute infections up to 14 days of onset of symptoms; (4) immunocompetent patients ≥ 16 years; (5) design of the study as randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, observational studies, or case series.

To limit heterogeneity, we only included AdV, H1N1, RNV, RSV, and PIV as these were the most prevalent pathogens of viral pneumonia in immunocompetent hosts in previous studies [42,43,44,45]. We did not include other influenza A strains, such as H7N9, H5N1, H1N2, and H3N2.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) study population that included immunocompromised and did not stratify the analysis from immunocompetent patients; (2) lack of data regarding age and/or immunocompetency status; (3) case reports or series with less than ten subjects, letters to the editor, reviews, or meta-analysis; (4) studies not published in English; (5) studies with animals or in vitro.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently reviewed all included articles to extract data. Disagreements were solved by consensus or with the assistant of a third reviewer with more than 10 years of experience in thoracic radiology. Imaging features were defined following the Fleischner Society’s glossary of terms in thoracic radiology [46].

From each study, we extracted the number of patients presenting the following imaging features: main CT pattern (predominantly or purely GGO; predominantly or purely consolidation; mixed GGO and consolidation; absence of GGO or consolidation), bilateral distribution; axial predominance (central; peripheral; random or diffuse); lobar predominance (upper lobes; middle lobes; lower lobes; random or diffuse (≥ 3 lobes).

Additionally, we also obtained the number of patients presenting the following chest CT findings: GGO, consolidation, nodules (tree-in-bud or centrilobular nodules), interstitial changes (interlobular septal thickening, reticulation, fibrosis), “crazy-paving” pattern, linear opacities, air bronchograms, bronchial wall thickening, vascular enlargement, reverse halo sign, pleural effusion, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

We only included data when studies described a per-patient report of the CT findings. As per-lesion analyses could be misleading, we considered the data as “not available” when the authors only described the absolute number of lesions, e.g., the number of GGO lesions. In studies which not all participating patients underwent a chest CT, we considered as the number of patients with a chest CT scan as the study sample size. When multiple publications including the same population was identified from an author group, we only included the most comprehensive study to avoid duplication of data.

Study quality assessment

Two reviewers independently rated the quality of included studies using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies [47]. Studies were not excluded due to their quality score to increase transparency and ensure all available evidence in this area was reported.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp LP). We used the Metaprop command to calculate the pooled prevalences of the included variables and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The I2 index was used to quantify the extent of heterogeneity. Due to limitations of the meta-analysis of variables with extreme proportions, i.e., zero (0%) or one (100%), the variable was added “n + 1” (in case of 0%) or subtracted “n-1” (in cases of 100%) when appropriate. Random-effects models were used as elevated levels of heterogeneity were expected due to differences in the population and methodology of the articles. We assessed the heterogeneity in main characteristics, including date of publication and study quality.

Results

Study characteristics

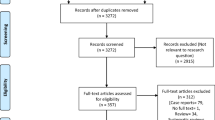

The initial search yielded 2263 studies, from which 96 were reviewed, and 33 met the inclusion criteria. A total of 10 studies on COVID-19 [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], and 23 studies on non-COVID viral pneumonias were included (Fig. 1) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Although the article by Ng et al included a 10-year-old child, this patient had a normal chest CT and was removed from this analysis [13]. A total of 1911 patients were included, of which 934 (48.9%) were in the COVID group and 977 (51.1%) were in the non-COVID group. Summary findings of the studies included in this meta-analysis were presented in Tables 1 and 2. Methodologic quality was considered fair in all the included studies [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Publication bias was not able to be assessed due to the heterogeneity in the means of reporting data among different studies. In the non-COVID studies, H1N1 was the main pathogen in 19, AdV in 4, and in one study, there were multiple pathogens in the sample (AdV, H1N1, RSV, and PIV).

Pooled prevalence of CT findings

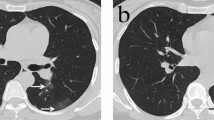

Main CT features of COVID-19 and other viral pneumonia are summarized in Table 3. COVID-19 most commonly manifested with either a predominantly GGO pattern (0.42; 95% CI 0.28–0.55) (Fig. 2a), or a mixed pattern of GGO and consolidation (0.37; 95% CI 0.17–0.56) (Fig. 3a). Non-COVID viral pneumonia most often presented a mixed pattern of GGO and consolidation (0.46; 95% CI 0.35–0.58) (Fig. 3b) that was more commonly seen compared with a predominantly GGO pattern (0.25; 95% CI 0.17–0.32) (Fig. 2b). The predominant consolidation pattern was the least common of both groups (COVID-19, 0.04; 95% CI 0.01–0.07; vs non-COVID, 0.17; 95% CI 0.11–0.23) (Fig. 4). Heterogeneity was high and significant for all analyses on predominant CT patterns in both groups.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of “predominantly or purely ground-glass opacity” as the main CT pattern in COVID-19 (a) and non-COVID (b) studies. This was the most common predominant pattern in patients with COVID-19, and the second most prevalent pattern in non-COVID viral pneumonia. Heterogeneity was high and significant for both COVID-19 and non-COVID studies

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of “predominantly or purely consolidation” as the main CT pattern in COVID-19 (a) and non-COVID (b) studies. This was the least common CT pattern for both COVID-19 and non-COVID patients. Heterogeneity was high and significant for both COVID-19 and non-COVID studies

In both COVID-19 and non-COVID viral pneumonia, chest CT findings were bilateral (COVID-19, 0.81; 95% CI 0.77–0.85; non-COVID, 0.69; 0.54–0.84) (Supplementary Fig. 1) and most often involved the lower lobes (COVID-19, 0.88; 95% CI 0.80–0.95; non-COVID, 0.61; 0.44–0.78) (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, COVID-19 pneumonia presented a higher prevalence of peripheral distribution (COVID-19, 0.77; 95% CI 0.67–0.87; non-COVID, 0.34; 95% CI 0.18–0.49) (Supplementary Fig. 3), and involvement of upper lobes (COVID-19, 0.77; 95% CI 0.65–0.88; non-COVID, 0.18; 95% CI 0.10–0.27) (Supplementary Fig. 4) and middle lobe (COVID-19, 0.61; 95% CI 0.47–0.76; non-COVID, 0.24; 95% CI 0.11–0.38) (Supplementary Fig. 5). The most prevalent axial distribution of lesions in non-COVID was a diffuse or random distribution (0.50; 95% CI 0.35–0.65).

GGO was the most common CT finding, found in up to 0.92 (95% CI, 0.90–0.97) of COVID-19 and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.74–0.85) of non-COVID (Supplementary Fig. 6), followed by consolidation (COVID-19, 0.50; 95% CI 0.33–0.66; non-COVID, 0.69, 95% CI 0.61–0.77) (Supplementary Fig. 7). Pleural effusion was rare in COVID-19 (0.03; 95% CI 0.01–0.04), but more common in other viral pneumonia (0.25; 95% CI 0.18–0.32) (Supplementary Fig. 8). A case of COVID-19 presenting the most prevalent CT findings is shown in Fig. 5. We also present a patient diagnosed with H1N1 and typical images features of COVID-19 (Fig. 6).

60-year-old man presenting with typical CT findings of COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR. a Axial chest CT demonstrates bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities with superimposed smooth interlobular septal thickening (crazy-paving). b Coronal reformatted CT shows bilateral upper to mid lung gradient, though the lower lobes were involved to a lesser extent

Discussion

The most prevalent chest CT findings in patients with COVID-19 were a predominantly GGO pattern (0.42; 95% CI 0.28–0·55), followed by a mixed pattern of GGO and consolidation (0.37; 95% CI 0.17–0.56), bilateral disease (0.81; 95% CI 0.77–0.85), and involvement of the lower lobes (0.88; 95% CI 0.80–0.95). The most prevalent findings in non-COVID viral pneumonia were a mixed pattern of GGO and consolidation (0.49; 95% CI 0.39–0.62), followed by a predominantly GGO pattern (0.25; 95% CI 0.17–0.32), bilateral disease (0.69; 95% CI 0.53–0.85), and involvement of the lower lobes (0.61; 95% CI 0.44–0.78). Compared with other viral pneumonia, COVID-19 demonstrated a higher prevalence of peripheral distribution (0.77; 95% CI 0.67–0.87), and involvement of upper (0.77; 95% CI 0.65–0.88) and middle lobes (0.61; 95% CI 0.47–0.76).

The prevalence of upper and middle zone disease observed in the non-COVID population is likely underestimated. Many authors in this group used the terms “random zone predominance” or “diffuse involvement” referring to patients with involvement of multiple or all lobes, instead of describing which individual lobes were affected [17, 18, 23, 34]. Thus, patients in these two categories were not included in the analysis of individual lobar distribution, even though some of them possibly had upper and middle zone involvement. All the COVID-19 studies individually described which lobes were affected in their population.

The use of chest CT scan as a primary tool for screening of patients under investigation for COVID-19 is fraught with significant issues [48, 49]. This approach will result in an increased number of CTs in stable patients that otherwise would not be scanned, leading to increased costs and reduced access to imaging suites, as the entire room would have to be extensively sanitized after every case with suspicion for COVID-19 [49, 50]. Moreover, the CT scanner may act as a fomite of COVID-19 transmission. Therefore, the American College of Radiology (ACR) urges caution on such approach as a standard CT (especially in the early phases of COVID-19) should not dissuade a patient from viral testing, quarantine, and appropriate treatment [51]. Also, an abnormal CT should not be seen as diagnostic, as the same pattern may be seen in other viral pneumonia, as demonstrated in this study. Such resemblance should be acknowledged as the COVID-19 emerged simultaneously to the current seasonal influenza in the Northern Hemisphere.

There are two systematic reviews on CT findings on COVID-19 available in the literature with similar results to our study regarding the most common imaging findings in COVID-19 [52, 53]. Nonetheless, our review differs from those two by not including case series of less than 10 patients, population with pediatric or immunocompromised patients, and studies in which a percentage of the population did not have the diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by PCR, such as Ai et al [6]. We still had high heterogeneity between studies, which could be attributed to several factors. First, chest CT features, such as the predominant imaging pattern, depending on the time course of the infection when the patient is scanned [8, 14, 54]. A predominant pattern of GGOs is expected in the early course of COVID-19, whereas a mixed pattern often peaks between the second and third week of infection [54]. To limit this temporal variation of findings, we only included cases of acute infection with up to 14 days of evolution. Another possible cause of inter-study heterogeneity was a non-standard description of the CT findings throughout the studies, which lead to a significant number of missing data. By including only immunocompetent patients, we tried to reduce such heterogeneity of CT findings. Differences in CT scanners and protocols can also be accounted for the high inter-study heterogeneity. Also, the higher prevalence of pleural effusion in non-COVID studies, especially in the studies by Henzler et al and Grieser et al, could be attributed to pulmonary congestion of critically ill patients rather than a common manifestation of viral pneumonia [29, 32].

Several studies herein discussed have attempted to determine the diagnostic accuracy of chest CT to diagnose COVID-19. However, many are at risk of bias due to methodology limitations, such as lack of a control population and questionable reference tests. As a result, CT estimates of sensitivity and specificity could be flawed [55]. For instance, Ai et al reported a sensitivity of 97% and suggested chest CT as a primary tool for the detection of COVID-19 in epidemic areas [6]. Bai et al also found that CT was abnormal in more than 90% of RT-PCR confirmed cases of COVID-19 [7]. On the other hand, Inui and colleagues described that only 61% of positive cases from Diamond Princess cruise ship had lung opacities on chest CT [10]. We believe the statistics of the latter comes closer to what would be expected in the general population, especially considering patients who are not very symptomatic and undergo chest CT scanning.

Bai et al investigated the performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from other viral pneumonia [7]. The authors found that American radiologists had a surprisingly high accuracy in distinguishing COVID-19 from other viral pneumonia. However, the reproducibility of these findings is questionable, as authors considered as references in the control group patients that had word “pneumonia” in their radiology CT reports and a positive result from respiratory pathogen panel. Also, bilateral GGOs have a much broader differential, present in atypical infections, non-infectious processes, and even in healthy individuals [40, 41]. Also, some patients with COVID-19 pneumonia may have a normal chest CT scan [50].

This study has some limitations. First, there were limitations common to any meta-analyses of diagnostic tests (e.g., selection bias, publication bias, missing information). Virtually all studies herein included had a retrospective design, which is also a limitation. The exclusion of studies not available in English could have increased the probability of publication bias. Regarding selection bias, the etiological agents of non-COVID studies were not entirely comprehensible for all viruses associated with community-acquired viral pneumonia (e.g., rhinovirus). Few studies using chest CT in immunocompetent adults are available, as CT imaging is considered “usually not appropriate” by the ACR in this scenario [51]. Also, the heterogeneity in the results was high due to the reasons discussed above. Finally, the methodology for measuring variables (e.g., axial distribution, predominant CT pattern) was not standardized among manuscripts.

Conclusion

Except for a higher prevalence of peripheral distribution, involvement of upper and middle lobes, COVID-19, and non-COVID viral pneumonia has overlapping chest CT findings. As such, caution should be exercised when interpreting chest CT for COVID-19 and the use of this imaging modality as a first-line test for COVID-19 diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Radiology

- AdV:

-

Adenovirus

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CT:

-

Chest tomography

- EQUATOR:

-

Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research

- GGO:

-

Ground-glass opacity

- MOOSE:

-

Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- PIV:

-

Parainfluenza virus

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

- RNV:

-

Rhinovirus

- RSV:

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W et al (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 382:727–733

Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D et al (2020) A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:1787–1799

World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (2019) Available via https//www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 5 Apr 2020

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497–506

Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382:1708–1720

Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H et al (2020) Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200642

Bai HX, Hsieh B, Xiong Z et al (2020) Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from viral pneumonia on chest CT. Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200823

Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M et al (2020) Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200463

Caruso D, Zerunian M, Polici M et al (2020) Chest CT features of COVID-19 in Rome, Italy. Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020201237

Inui S, Fujikawa A, Jitsu M et al (2020) Chest CT findings in cases from the cruise ship “Diamond Princess” with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.2020200110

Li Y, Xia L (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): role of chest CT in diagnosis and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol 4:1–7

Liu K-C, Xu P, Lv W-F et al (2020) CT manifestations of coronavirus disease-2019: a retrospective analysis of 73 cases by disease severity. Eur J Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108941

Ng M-Y, Lee EY, Yang J et al (2020) Imaging profile of the COVID-19 infection: radiologic findings and literature review. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.2020200034

Pan Y, Guan H, Zhou S et al (2020) Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-06731-x

Song F, Shi N, Shan F et al (2020) Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology 295:210–217

Shi H, Han X, Jiang N et al (2020) Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 20:425–434

Amorim VB, Rodrigues RS, Barreto MM, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, Marchiori E (2013) Influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia: HRCT findings. J Bras Pneumol 39:323–329

Cho WH, Kim YS, Jeon DS et al (2011) Outcome of pandemic H1N1 pneumonia: clinical and radiological findings for severity assessment. Korean J Intern Med 26:160

Li P, Su DJ, Zhang JF, Xia XD, Sui H, Zhao DH (2011) Pneumonia in novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection: high-resolution CT findings. Eur J Radiol 80:146–152

Li H, Weng H, Lan C et al (2018) Comparison of patients with avian influenza A (H7N9) and influenza A (H1N1) complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e0194

Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B et al (2010) High-resolution computed tomography findings from adult patients with influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia. Eur J Radiol 74:93–98

Nicolini A, Ferrera L, Rao F, Senarega R, Ferrari-Bravo M (2012) Chest radiological findings of influenza A H1N1 pneumonia. Rev Port Pneumol 18:120–127

Park CK, Kwon H, Park JY (2017) Thin-section computed tomography findings in 104 immunocompetent patients with adenovirus pneumonia. Acta Radiol 58:937–943

Qi W, Gao S, Liu C, Shinong P, Guo Q (2014) Computed tomographic features of pregnant women with pandemic H1N1 virus infection. Radiol Infect Dis 1:23–27

Shiley KT, Van Deerlin VM, Miller WT (2010) Chest CT features of community-acquired respiratory viral infections in adult inpatients with lower respiratory tract infections. J Thorac Imaging 25:68–75

Sohn CH, Ryoo SM, Yoon JY et al (2013) Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of hospitalized adult patients with novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia and other pneumonia. Acad Emerg Med 20:46–53

Son JS, Kim YH, Lee YK et al (2011) Pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral pneumonia without co-infection in Korea: Chest CT findings. Tuberc Respir Dis 70:397–404

Song JY, Cheong HJ, Heo JY et al (2011) Clinical, laboratory and radiologic characteristics of 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 pneumonia: primary influenza pneumonia versus concomitant/secondary bacterial pneumonia. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 5:535–543

Grieser C, Goldmann A, Steffen IG et al (2012) Computed tomography findings from patients with ARDS due to influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia. Eur J Radiol 81:389–394

Tanaka N, Emoto T, Suda H et al (2012) High-resolution computed tomography findings of influenza virus pneumonia: a comparative study between seasonal and novel (H1N1) influenza virus pneumonia. Jpn J Radiol 30:154–161

Valente T, Lassandro F, Marino M, Squillante F, Aliperta M, Muto R (2012) Polmonite H1N1: La nostra esperienza in 50 pazienti con decorso clinico grave dell’influenza virale A di origine suina (S-OIV). Radiol Med 117:165–184

Henzler T, Meyer M, Kalenka A et al (2010) Image findings of patients with H1N1 virus pneumonia and acute respiratory failure. Acad Radiol 17:681–685

Hwang SM, Park DE, Yang YI et al (2013) Outbreak of febrile respiratory illness caused by adenovirus at a south Korean military training facility: clinical and radiological characteristics of adenovirus pneumonia. Jpn J Infect Dis 66:359–365

Kang H, Lee KS, Jeong YJ, Lee HY, Kim KI, Nam KJ (2012) Computed tomography findings of influenza a (H1N1) pneumonia in adults: pattern analysis and prognostic comparisons. J Comput Assist Tomogr 36:285–290

Karadeli E, Koç Z, Ulusan Ş, Erbay G, Demiroǧlu YZ, Şen N (2011) Chest radiography and CT findings in patients with the 2009 pandemic (H1N1) influenza. Diagn Interv Radiol 17:216–222

Kim SY, Kim JS, Park CS (2011) Various computed tomography findings of 2009 H1N1 influenza in 17 patients with relatively mild illness. Jpn J Radiol 29:301–306

Ishiguro T, Takayanagi N, Kanauchi T et al (2016) Clinical and radiographic comparison of influenza virus-associated pneumonia among three viral subtypes. Intern Med 55:731–737

Lee JE, Choe KW, Lee SW (2013) Clinical and radiological characteristics of 2009 H1N1 influenza associated pneumonia in young male adults. Yonsei Med J 54:927–934

Yoon H, Jhun BW, Kim H, Yoo H, Park SB (2017) Characteristics of adenovirus pneumonia in Korean military personnel, 2012-2016. J Korean Med Sci 32:287–295

Winter DH, Manzini M, Salge JM et al (2015) Aging of the lungs in asymptomatic lifelong nonsmokers: findings on HRCT. Lung 193:283–290

Copley SJ, Wells AU, Hawtin KE et al (2009) Lung morphology in the elderly: comparative CT study of subjects over 75 years old versus those under 55 years old. Radiology 251:566–573

Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG et al (2015) Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 373:415–427

Jennings LC, Anderson TP, Beynon KA et al (2008) Incidence and characteristics of viral community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax 63:42–48

de Roux A, Marcos MA, Garcia E et al (2004) Viral community-acquired pneumonia in nonimmunocompromised adults. Chest 125:1343–1351

Oosterheert JJ, van Loon AM, Schuurman R et al (2005) Impact of rapid detection of viral and atypical bacterial pathogens by real-time polymerase chain reaction for patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Clin Infect Dis 41:1438–1444

Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J (2008) Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 246:697–722

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Study quality assessment tools. Available at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 1 April 2020

Rubin GD, Ryerson CJ, Haramati LB et al (2020) The role of chest imaging in patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational consensus statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020201365

Kooraki S, Hosseiny M, Myers L, Gholamrezanezhad A (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of radiology should know. J Am Coll Radiol 17:447–451

Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S et al (2020) Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Statement on Reporting Chest CT Findings Related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1097/RTI.0000000000000524

American College of Radiology. ACR recommendations for the use of chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) for suspected COVID-19. Available at https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed 4 Apr 2020

Bao C, Liu X, Zhang H, Li Y, Liu J (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) CT findings: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Coll Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.006

Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 14:1–7

Wang Y, Dong C, Hu Y et al (2020) Temporal changes of CT findings in 90 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a longitudinal study. Radiology. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200843

Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG et al (2016) STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 6:e012799

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Bruno Hochhegger, MD, PhD.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

One of the authors has significant statistical expertise.

Informed consent

Not applicable since this was a systematic review and did not include information on human subjects.

Ethical approval

Not applicable since this was a systematic review and did not include information on human subjects.

Methodology

• Systematic review and meta-analysis

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 2.48 mb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Altmayer, S., Zanon, M., Pacini, G.S. et al. Comparison of the computed tomography findings in COVID-19 and other viral pneumonia in immunocompetent adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 30, 6485–6496 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07018-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07018-x