To mark China’s Spring Festival last month, Xi Jinping made a visit to the small northern village of Liangjiahe, where he was banished in 1969 as a raw 15-year-old during the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, where he worked for seven years and where the future president of China joined the Communist party.

His father had been persecuted and jailed in one of Mao Zedong’s purges, and Xi suffered humiliation, hunger and homelessness, sleeping in a cave, carrying manure and building roads, according to official accounts. “Perplexed” when he was sent to the countryside, Xi emerged as if remoulded by the painful years he spent there. He learned enough in the village to be able to cast himself as a man of the people. The lessons also made him profoundly distrust those same people.

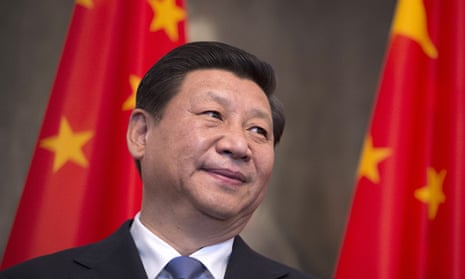

Xi told villagers that he had left his heart in Liangjiahe, but it was clear that the experience has stayed with him in ways both spoken and unspoken, and has helped shape the sort of president he has become – possibly the strongest Chinese leader since Mao.

In September, Xi will pay a state visit to the United States, as a president who has ruthlessly centralised power while embarking on an ambitious project to revitalise Communist rule and to secure the party’s future. He is also a president whose worldview, and vision for China, were shaped by two historic traumas.

The first was the trauma of the Cultural Revolution, when Mao used the people to tear his own party to shreds, and Xi was caught up in the chaos. The second was the trauma of the collapse of the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991, as the public was invited to rise up and the Communist party there was consigned to oblivion.

For if Xi casts himself as the man to save the Communist party from its demons, he is also a man obsessively determined to retain full control of any reform process, in ways that Mao and Gorbachev did not do.

The twin traumas help explain why he won’t allow the people to drive any process of change. His determination to crack down on corruption, for example, is matched by an equal resolve to exclude the public from participating in that campaign, lest the forces he unleashes spin out of control.

“The combination of that domestic trauma, experienced as a young person, and the trauma of the collapse of the Soviet Union, those two traumas, one domestic and one foreign, have really shaped him,” said Roderick MacFarquhar, a leading expert in Chinese politics at Harvard University. “He has seen what happens if you allow too much criticism of the party and the establishment.”

Gorbachev and Mao both struggled against opposition and factionalism within their own parties, although they pursued far different remedies. Xi is determined to consolidate power and eliminate rivals. He has experienced firsthand the chaos that ensues when the party disintegrates, and that helps explain his desire to reinvigorate the Chinese Communist party and reassert its primacy.

One of his major themes is a war on “western values”, including a free press, democracy and the constitutional separation of powers, all of which he believes pose an insidious threat to one-party rule.

In this and in the growing ideological controls on sectors ranging from the news media to the military, Xi is resisting forces that he thinks brought the Soviet regime to its knees. Paradoxically, though, he also has seen the dangers of international isolation and an inward focus, factors that helped weaken Mao’s China and the Soviet Union. That paradox, between “reform and opening” on the one hand and excluding western values on the other, has created an unresolved tension in his presidency.

Cheng Enfu, the director of the Institute of Marxism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, predicted that the president’s efforts to combat this “infiltration” of western values could become as intense as his anti-corruption campaign.

Xi considers himself the antithesis of the “weak man” who turned out the light on the Soviet empire. “Proportionally, the Soviet Communist party had more members than we do, but nobody was man enough to stand up and resist,” Xi reportedly said in an important speech shortly after taking over leadership of the Communist party in late 2012.

Today, Xi presents himself as a down-to-earth leader who rolled up his sleeves and learned the hard way during those years working with peasants in the countryside. In that sense, he casts himself as a worthy successor to Mao. But, although he would never admit it, he has learned from Mao’s mistakes as well.

While Mao’s Cultural Revolution almost destroyed China, Xi’s war on corruption is a masterpiece in controlled destruction. More than 100,000 party members have been disciplined since the campaign began, but through a process that is entirely managed from within the party. The public is simply not invited to join in, while anti-corruption activists have received long prison sentences. There are to be no mass denunciations of corrupt and arrogant officials, because Xi remembers only too well where that path leads.

“He needs to fully control the anti-corruption movement, because they are afraid that the participation of the public will lead to another cultural revolution and bring more chaos,” historian Zhang Lifan said.

The Soviet collapse – blamed in part in China on corruption – still haunts the Chinese Communist party, said David Shambaugh, director of the China Policy Program at George Washington University. An entire industry has grown up to pore over the reasons for the collapse and ask what lessons can be drawn from it.

Initially, China mostly faulted Gorbachev himself as a weak and foolish leader. But in the years that followed, Shambaugh says, Chinese party scholars eventually pegged the Soviet collapse on the rot within – not only corruption but also economic and political stagnation and international isolation.

Gorbachev was stymied by opposition from within the Soviet bureaucracy; the strength of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign is that it reforms the party while asserting his supremacy over it.

Xi also has tried to counter the party’s ideological loss of direction with a new narrative: that the party should be proud of itself and have confidence in its historical right to rule. Mao, consigned to the bookshelf of history since the era of Deng Xiaoping and China’s great opening to the world, has to be dusted off and revered again as the victor of the revolution and the unifier of the nation.

“Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist party collapse?” Xi asked in that December 2012 speech. “It’s a profound lesson for us. To dismiss the history of the Soviet Union and the Soviet Communist party, to dismiss Lenin and Stalin, and to dismiss everything else is to engage in historic nihilism, and it confuses our thoughts and undermines the party’s organisations on all levels.”

The problem, MacFarquhar says, is that Xi has no coherent or convincing new ideology to offer.

“He has got no positive weapon against the western infiltration of ideas, so he has to be negative about it,” he said. “It’s a tremendous contradiction he faces, to keep western ideas out while building a creative, technological and developed society.”

Shambaugh said the Chinese Communist party used to believe that the Soviet Union’s collapse meant it had to adapt and reform, to become dynamic and responsive. But it began to abandon that strategy from 2008, as it faced another series of small traumas: riots in Tibet and Xinjiang, popular uprisings, including the “colour revolutions” and the Arab Spring, and internal dissent as the internet empowered citizens and intellectuals demanded democracy.

Once again, the conservatives dug in and laid their bets not on adaptation but on repression. Xi, Shambaugh said, has intensified the repression begun under his predecessor, Hu Jintao.

So when a new video series about the fall of the Soviet Union became compulsory viewing for Communist party cadres in 2013, its focus was not on the flaws in the Soviet system but – once again – on the sins of Gorbachev.

“Western values played a leading role in the failure of Gorbachev’s reform effort, and the documentary aims to warn cadres not to make the same mistake as Gorbachev,” said Cheng.

“Gorbachev introduced outside forces to help him to turn over the Soviet Communist party. Xi believes the Communist party can self-correct. The party is able to hunt the problem and fix it itself. Communist reform is controllable.”

This article appeared in Guardian Weekly, which incorporates material from Washington Post

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion